Knee Pathology

Tendons

Patellar Tendon

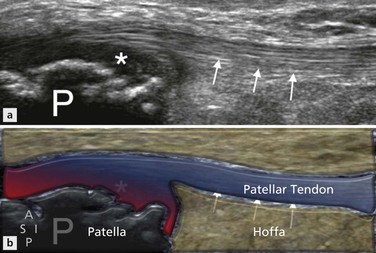

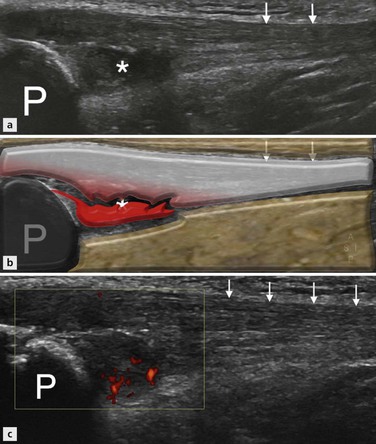

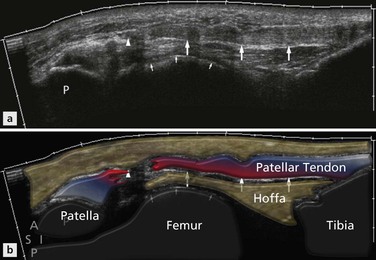

The patellar tendon is a relatively superficial structure readily examined by ultrasound. Patellar tendinopathy is a condition commonly caused by overuse, particularly as a result of running and jumping activities; it has been also termed ‘jumper’s knee’ and is thought to result from chronic microtrauma to the tendon. Patients usually present with anterior knee pain that is most frequently localized over the lower pole of the patella. Appearances on ultrasound are of disruption of the normal fibrillar pattern and thickening of the tendon with focal areas of hypoechoic change within it, associated with neovascularity within the tendon as a result of vascular in-growth (Fig. 22.1).

Figure 22.1 Patellar tendinopathy. (A, B) Longitudinal image of the anterior aspect of the knee showing the patellar and proximal patellar tendon (white arrows) in a patient with patellar tendinopathy. There is marked thickening of the deep portion of the proximal tendon with corresponding hypoechoic change (*). (C) Power Doppler imaging in the same patient reveals neovascularity in the area affected by hypoechoic change.

The localized nature of the disease means it is important to evaluate both the whole length and width of the tendon using both longitudinal and transverse views.

Neovascularization is best demonstrated on power Doppler imaging with the knee extended and with only light probe pressure over the tendon.

The paratenon may be the site of acute inflammation, although this is more commonly seen at the Achilles tendon; paratenonitis manifests on ultrasound as an echo-poor halo around the tendon which often shows increased vascularity on power Doppler imaging . Less commonly, tendinopathy may be seen distally in the tendon close to the tibial attachment, although this is most frequently seen in adolescents as part of the spectrum of changes seen in Osgood–Schlatter’s disease.

Tendinopathy involving the entire tendon is not usually related to physical activity but to systemic disorders leading to infiltration of the tendon, such as gout and hypercholesterolaemia (Fig. 22.2).

Figure 22.2 Gout tendinopathy. Longitudinal image of the proximal patellar tendon (arrowheads) just distal to the patellar origin shows the tendon to have heterogeneous echotexture and diffuse thickening with loss of the normal fascicular architecture. The patient was known to have gout and features are suggestive of gout tendinopathy.

Rupture of the patellar tendon may occur, resulting in a complete disruption of the extensor mechanism. This most frequently occurs on a background of preexisting tendinopathic change or in the presence of systemic inflammatory conditions such as diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLF) or chronic renal failure. Both systemic steroids and local steroid injections have also been shown to be contributing factors. Following rupture, a high-riding patella may be detected on clinical examination or conventional radiography as a result of retraction by the quadriceps mechanism (Fig. 22.3). On ultrasound, patella alta results in the trochlear groove, normally hidden behind the patella, becomes visible, while examination of the tendon itself will demonstrate the discontinuity (Fig. 22.4). Interposed haematoma may make visualization of the tendon ends difficult; however, dynamic assessment of the tendon should allow differentiation of partial- from full-thickness injury.

Figure 22.3 Patellar tendon rupture. Horizontal beam lateral view of the knee joint showing a high-riding patella, indicating a full-thickness tear of the patellar tendon with subsequent proximal retraction of the patella.

Figure 22.4 Patellar tendon rupture. Longitudinal image of the anterior aspect of the knee showing the patellar tendon (large arrows) with a full-thickness tear of the proximal tendon (arrowheads). Note the exposed anterior surface of the femoral trochlea (small arrows) as a result of the elevated position of the patella.

Osgood–Schlatter’s Disease

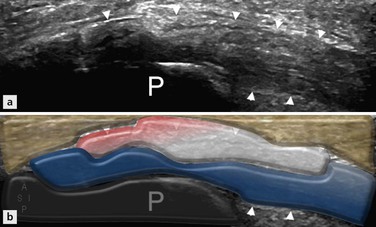

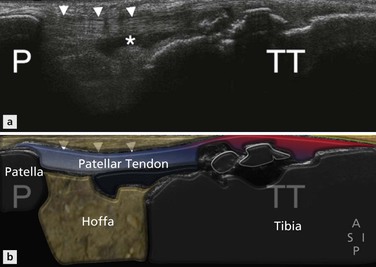

Chronic inflammation of the insertion of the patellar tendon onto the tibial tuberosity may be seen in adolescents (Fig. 22.5). This condition, called Osgood–Schlatter’s disease, represents a traction enthesopathy and is characterized by irregularity of the tibial tuberosity. The tibial tuberosity may be irregular in asymptomatic patients and care should be taken to avoid overdiagnosing this condition. Reactive secondary heterotopic bone formation occurs at the insertion site of the patellar tendon, resulting in a visible and palpable lump: the main physical finding in Osgood–Schlatter’s disease. A similar condition occurring at the patellar insertion is termed Sindig-Larsen–Johansson syndrome. On ultrasound, thickening of the patellar tendon at the insertion site with low-reflective change and associated intratendinous calcification is seen (Fig. 22.6). Neovascularization may also be present in the tendon and peritendinous bursitis may also be shown. Ultrasound will also demonstrate bony surface irregularity and/or fragmentation of the tibial tuberosity (Osgood–Schlatter’s disease) or lower pole of the patella (Sindig-Larsen–Johansson syndrome).

Figure 22.5 Osgood–Schlatter’s disease. Longitudinal image of the patellar tendon in a young patient with anterior knee pain. The proximal patellar tendon (arrowheads) has normal sonographic appearances. The tibial tuberosity is shown to have an irregular anterior cortex at the site of insertion of the patellar tendon, which itself shows hypoechoic change. An effusion is also seen within the deep infrapatellar bursa consistent with bursitis (*).

Quadriceps Tendon

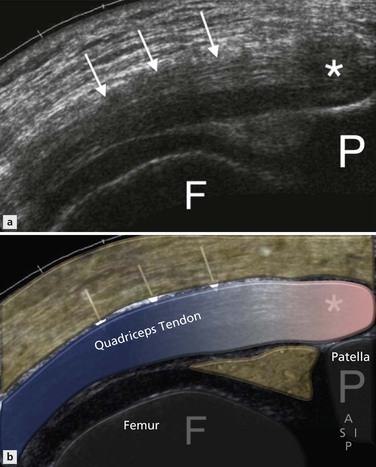

The quadriceps tendon is less commonly affected by tendinopathic change than the patellar tendon and when seen it usually relates to persistent strenuous overuse. Clinically the condition presents as focal pain over the distal portion of the tendon and will manifest on ultrasound as a focal area of hypoechoic change within a portion of the tendon, loss of definition of the normal trilaminar appearance and intratendinous vascularity. Transverse imaging of the tendon is often helpful in more accurately defining the precise location of the tendinopathic change. More rarely the full thickness of the tendon is involved and appearances will be of diffuse thickening of the tendon with heterogeneous echotexture throughout (Fig. 22.7).

Figure 22.7 Quadriceps tendinopathy. Longitudinal image of the distal quadriceps tendon and insertion showing thickening of the tendon (white arrows) with a diffusely heterogeneous echotexture thoughout. There is also more focal distal hypoechoic change (*).

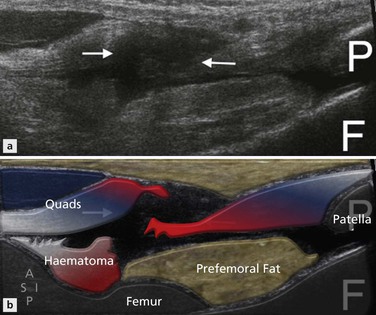

Rupture of the quadriceps tendon is a relatively rare phenomenon.

Differentiation between a full and a partial thickness tear is important for management purposes and may be difficult to determine clinically. Ultrasound imaging of a partial tear will reveal discontinuity of one of the layers of the tendon close to the patellar insertion, often with retraction of the torn fibres but with other, usually deep fibres, intact. Dynamic assessment of the tendon may help in establishing this picture. Full-thickness tears will often have haematoma interposed between the two tendon ends with no continuous fibres seen crossing the gap (Fig. 22.8). In the presence of a complete quadriceps rupture the patellar tendon will often have a crumpled appearance due to lack of proximal traction on the patella: this sign may help distinguish a complete from a partial tear where there is doubt.

Figure 22.8 Quadriceps rupture. Longitudinal image of the distal quadriceps tendon lying superficial to the distal femur and inserting into the patella shows a full-thickness tear of the extensor tendon (arrows) with retraction of the proximal portion of the tendon.

The squeeze test involves lateral compression of the joint in an attempt to force joint fluid into the prepatellar space. This can only occur in the presence of a full-thickness defect.

Other Tendons

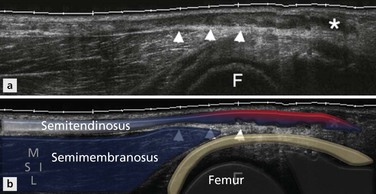

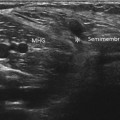

Other tendons around the knee may also become tendinopathic and may rarely rupture. Most commonly involved is the semimembranosus tendon which presents with pain in the posteromedial aspect of the joint. The insertion of this tendon is difficult to visualize on ultrasound due to its depth and MRI may be more helpful in delineating pathology here. Tendinopathy of the distal biceps femoris, semitendinosus (Fig. 22.9), gracilis and sartorius also occur. Distal biceps femoris rupture most often occurs in conjunction with lateral collateral ligament disruption, often in association with an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear of the knee.