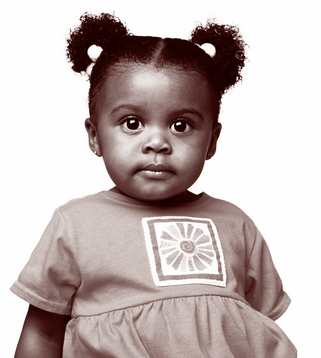

CHAPTER 12 On completion of this chapter, you should be able to: • Describe the defining characteristics of different age groups. • Discuss how these characteristics will influence your interactions with them. • Explain the legal implications in dealing with the very young and the very old. • List the several precautions to take to ensure the patient’s safety while he or she is in your care. • Explain why radiation protection practices are more important for the very young and for the very old. In Chapter 2, you learned that all people have the same basic needs, but other needs will arise that are specific to a situation or circumstance. For example, an infant’s needs are different from the needs of an adult, and an illness at any age presents different needs. Knowing something about your patients and the characteristics of the different age groups and cultures will help you interact with them while they are in your care. It is true—patient care means CARING for the patient. Patient care is more than passive empathy. Genuine caring is an active endeavor. Your caring involves more than producing a diagnostic quality examination. It involves doing no harm while performing the examination. Using the proper technique is the practical and only acceptable way to prevent harming your patient by unnecessary exposure to radiation. Infants are children during the earliest periods of life. They are afraid of two things, falling and loud noises. Safe, gentle handling of the infant while in your care is the first concern. If it is true, as some think, that an individual decides within the first 10 days of life whether he or she likes this world, you would not want your treatment of a newborn to influence this negatively. Although hard evidence for this belief may be difficult to find, gentle handling of a newborn is always in order. You will be interacting with some infants who have to go through a great deal of painful treatments in the first few days of life (Fig. 12-1). FIGURE 12-1 Infants are children during the earliest periods of life. (From Getty Images, Seattle, Wash.) The first order of safety is preventing physical harm and preventing unwanted exposure or overexposure to radiation. Radiation exposure is more critical to infants than to individuals in any other age group. This is the time to be reminded of the Law of Bergonie and Tribondeau, which is based on the sensitivity of cells to ionization radiation. The law states that cells are most sensitive to the effects of ionization radiation when they are rapidly dividing. This is important to remember because the most rapid growth period in an individual’s life is during infancy. Cells are dividing very rapidly thus the infant is most likely to be affected by radiation.* When radiographing infants, using radiation protection devices and irradiating only the anatomic part in question are critically important. By the time children are 3 years of age, a sense of right and wrong has begun to develop (Fig. 12-2). They have some concept of property and know what belongs to them and what belongs to others. If discipline has been consistent, they will begin to behave in a socially acceptable manner. The behavior may not always be consistent, but children will know the difference between right and wrong. Their reasoning ability may not be developed at this time; that is, they may not know why certain acts are not socially acceptable. In other words, they do not always seem to know what is acceptable and what is not.

Knowing Your Patient

Knowing your patient

Infants

Children (1 to 3 Years)

Knowing Your Patient