Choanal Atresia/Stenosis

Choanal atresia is a congenital obstruction of the nasopharynx. It is characterized by narrowing and closure of the posterior choanae, and medialization of the pterygoid plates and lateral walls of the nose.

7,

29 The most common etiology of neonatal nasal obstruction, choanal atresia has an estimated incidence of 1 in 5,000 to 1 in 9,000 births. It arises twice as frequently in females as in males and is more commonly unilateral than bilateral.

7,

29,

30 Osseous obstruction of the choanae was previously thought to be most common (90%), with membranous obstruction comprising the remaining 10%.

29 However, more recent data point to a mixed bony/membranous etiology in 70% of cases and a pure bony abnormality in 30%. Unilateral choanal atresia may be asymptomatic; later in life, the patient may present with nasal stuffiness, rhinorrhea, or infection. Inability to pass a nasal enteric tube should raise clinical suspicion. Bilateral choanal atresia can cause severe respiratory distress because neonates are obligate nose breathers.

7 Approximately 50% of patients with choanal atresia have associated anomalies such as coloboma, heart defects, and mental retardation, and syndromes including CHARGE (coloboma, heart disease, choanal atresia, growth and mental retardation, genital hypoplasia, ear anomalies with deafness), Crouzon, Pfeiffer, Antley-Bixler, Marshall-Smith, Schinzel-Giedion, and Treacher Collins.

7,

29,

31CT is most useful for demonstrating the precise anatomic abnormalities.

7,

32 Characteristic findings include narrowing of the posterior choanae to a width <0.34 cm in children under 2 years of age, inward bowing of the posterior maxilla, fusion or thickening of the vomer, and a bone or soft tissue septum across the posterior choanae (

Fig. 2.14).

7,

33 Severe choanal stenosis may mimic atresia. CT virtual endoscopy is a 3D postprocessing technique that requires ˜10 additional minutes per examination, but no additional radiation, and can be helpful in diagnosis and preoperative planning.

34 Some advocate instillation of 1 to 3 drops diluted nonionic contrast material through the nostril to better assess communication of the posterior choanae with the nasopharynx.

35Surgery is the management of choice for choanal atresia/stenosis. This consists of perforation of the obstructing septum to create a permanently patent airway.

7 Many surgical techniques are available, including transnasal puncture, transpalatal resection, stent placement, endoscopic resection, and choanal resection, although there is no clearly preferred strategy.

7,

29,

31 Correction of unilateral choanal atresia can be delayed until 6 to 9 years of age, when the midface reaches near-adult size.

7 In contrast, bilateral choanal atresia mandates immediate intervention to reestablish airway patency. CT-navigation systems may be useful in complex cases. Adjuncts such as mitomycin C and laser therapy demonstrate no definite benefit.

29 Ultimately, surgical success depends on the type of atresia, approach used, type of stent and duration of placement, and presence of other anomalies.

7

Congenital Pyriform Aperture Stenosis

Congenital nasal pyriform aperture stenosis (CNPAS) is characterized by excessive growth of the medial nasal processes of the maxilla.

7 It is a rare cause of upper airway obstruction in the newborn. The clinical presentation may include respiratory distress, episodic apnea, cyclical cyanosis, or sudden complete airway obstruction.

36,

37 Inability to pass a 5 French (F) catheter or endoscope through the nasal cavity is a classic history.

36 Clinically, CNPAS cannot be distinguished from bilateral choanal atresia.

7 The disorder may be part of the holoprosencephaly spectrum; a single central maxillary incisor is reported in up to 75% of cases, along with central nervous system (CNS) abnormalities.

7,

33,

36,

37 Additional associations include pituitary hormonal deficiencies and chromosomal abnormalities.

7,

36,

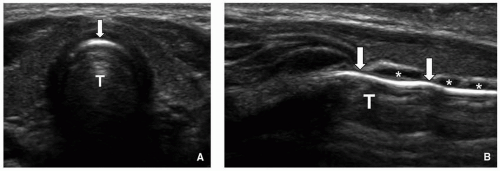

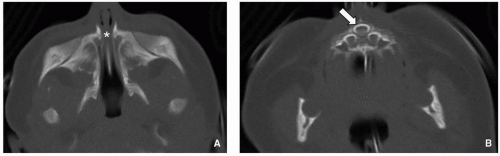

37CT is the imaging test of choice. Thin (1.5 to 2 mm) contiguous axial images are typically acquired parallel to the hard palate and roof of the orbits. Multiplanar 2D reformats are helpful but not mandatory to make the diagnosis. Findings include soft tissue density extending across the nostrils just

inside the nares, overgrowth and medial displacement of the nasal processes of maxilla, and narrowing of the pyriform aperture (

Fig. 2.15). The pyriform aperture is bounded by the nasal bones superiorly, the nasal processes of the maxilla laterally, and the horizontal processes inferiorly; a width <11 mm in a term infant is considered diagnostic of CNPAS.

7,

36,

38,

39 MR is used to assess for associated intracranial abnormalities.

40Mild CNPAS can be treated conservatively with humidification, topical nasal decongestants, nasal stenting, and placement of an oropharyngeal airway. More severe disease may necessitate surgical intervention.

7,

36,

37,

40 However, with treatment, the prognosis is excellent.

36

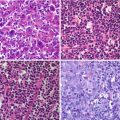

Adenoid and Palatine Tonsil Enlargement

Pathologic enlargement of the normally immunoprotective adenoid and palatine tonsils is a frequent cause of upper airway obstruction in children (

Fig. 2.16). The adenoid is an aggregation of lymphoid tissue located in the nasopharyngeal roof just beneath the sphenoid sinus and anterior to the basiocciput. It is absent at birth and rapidly grows during infancy, reaching a maximum size of 7 to 12 mm by 2 years of age, and progressively decreasing in size during puberty.

7,

21,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45 The palatine (faucial) tonsils are also masses of lymphoid tissue, bounded by the glossopalatine and pharyngopalatine arches. Chronic inflammation or infection leading to hypertrophy/enlargement of the adenoid and palatine tonsils can ultimately cause nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal obstruction. In turn, affected pediatric patients may develop chronic hypoxemia and hypercarbia from hypoventilation and obstructive sleep apnea.

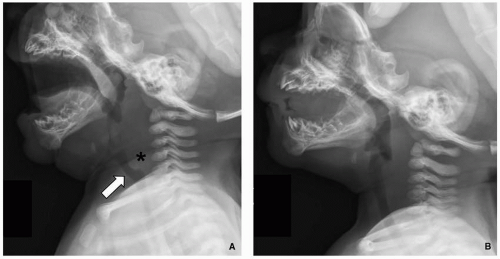

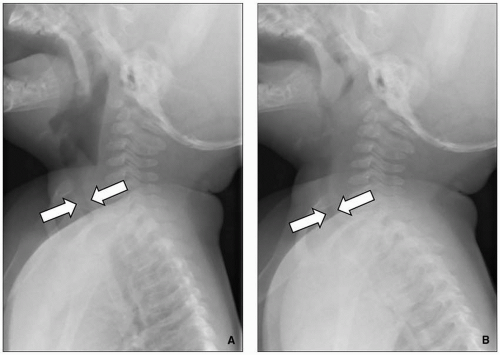

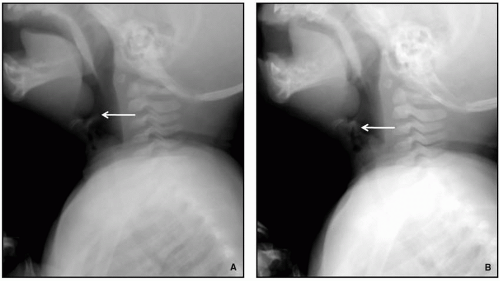

Radiography remains first-line in the evaluation. The adenoid is considered enlarged if it appears to touch the hard palate on a lateral upper airway view (

Fig. 2.17). Some advocate calculating the adenoidal-nasopharyngeal ratio (size of the adenoid relative to the nasopharynx). A value >0.8 is suggestive of adenoidal enlargement. The palatine tonsils are considered enlarged when they extend into the hypopharynx.

7,

46,

47 The tonsillar-pharyngeal (T/P) ratio, or width of the tonsil divided by depth of the pharyngeal space on a lateral neck radiograph, may be used to screen children with suspected obstructive sleep apnea.

2,

48 Traditionally, sedated video fluoroscopy has been used for dynamic airway evaluation.

2,

48 A more recent alternative is cine MRI, which can provide volumetric measurements of the tonsils and adenoid in addition to dynamic airway assessment.

2,

21,

49Antibiotics are used to treat active adenoid and tonsillar infection (with associated lymphoid tissue enlargement). For chronic enlargement, especially when associated with airway compromise or obstructive sleep apnea, adenoidectomy and/or tonsillectomy may be necessary. Surgery may also help manage recurrent ear and sinus infections.

7

Macroglossia

Macroglossia is characterized by chronic and painless enlargement of the tongue, defined by protrusion of the tongue beyond the teeth or alveolar ridge at rest. It should be distinguished from acute glossitis, in which there is painful and rapid tongue enlargement.

7,

50 Causes of macroglossia include hypothyroidism, idiopathic hyperplasia, and a number of syndromes including the mucopolysaccharidoses, Down, and Beckwith-Wiedemann.

7,

51,

52 A variant known as relative macroglossia refers to a normal-sized tongue that is large relative to a small-sized mandible (micrognathia). Macroglossia may present with noisy breathing, drooling, dysphagia, and speech difficulty, with potential for upper airway obstruction.

7,

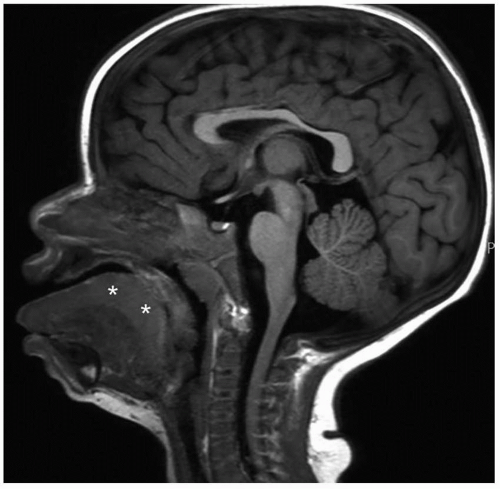

52,

53Sleep fluoroscopy can be used to evaluate for progressive respiratory distress in affected pediatric patients. During sleep, the enlarged tongue may fall posteriorly and obstruct the posterior pharynx.

7,

54 Cross-sectional imaging with CT and MRI is also helpful in assessing the tongue and excluding underlying masses (

Fig. 2.18).

7,

55Medical management may be sufficient for macroglossia related to an underlying systemic process. In other cases, surgery with reduction glossectomy is the treatment of choice in symptomatic patients, helping to prevent airway, speech, and orthodontic sequelae. Acute upper airway obstruction mandates immediate evaluation and intervention such as tracheostomy.

7,

55

Laryngomalacia

Laryngomalacia is characterized by abnormal laxity of the pharyngeal soft tissues due to immaturity of the laryngeal cartilages and muscles. It is a benign and often transient condition. The laxity causes inspiratory collapse of the epiglottis, arytenoids, and aryepiglottic folds with resultant partial upper airway obstruction. Laryngomalacia is the most frequent congenital laryngeal anomaly, accounting for >75% of such cases.

7,

56,

57 In addition, it is the most common cause of symptomatic airway obstruction in infants presenting with stridor that worsens with rest and improves with activity.

7,

56,

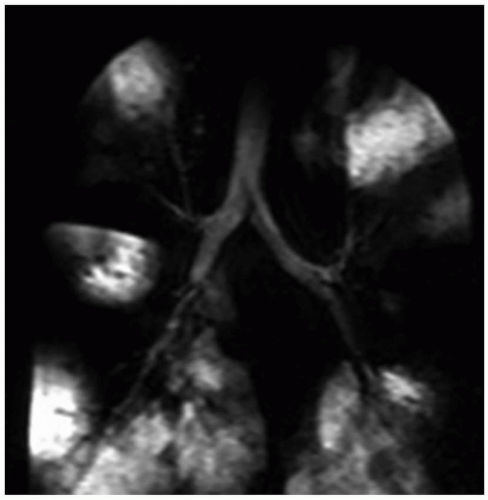

57Airway fluoroscopy characteristically shows downward and posterior bending of the epiglottis and anterior buckling of the aryepiglottic folds, with narrowing and eventually occlusion of the upper airway (

Fig. 2.19). Although airway fluoroscopy demonstrates high specificity for the diagnosis, its sensitivity is poor. Therefore, even when fluoroscopy is normal, further evaluation with laryngoscopy should be performed if there is persistent clinical concern.

7,

56,

58,

59,

60The majority of cases of laryngomalacia resolve without intervention by the end of the first year of life.

7 Acid-suppressing medication should be given in patients with concurrent feeding symptoms.

60 Persistent symptoms require surgical intervention to prevent complications such as airway obstruction and even sudden death. Relevant surgical techniques include tracheostomy, supraglottoplasty, aryepiglottic fold incision, and epiglottopexy.

7,

61

Laryngeal Cleft

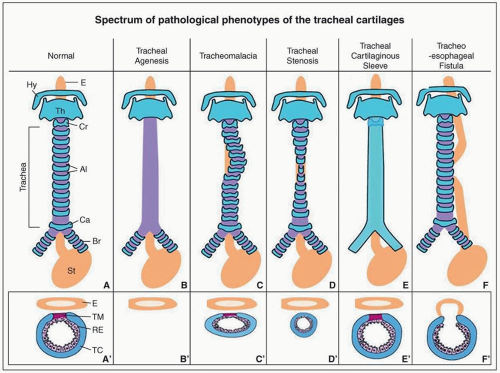

Laryngeal cleft is a congenital anomaly characterized by failure of fusion of the posterior aspect of the larynx, resulting in abnormal communication between the airway and esophagus.

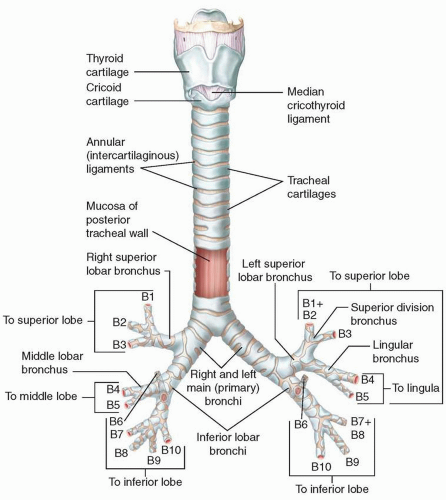

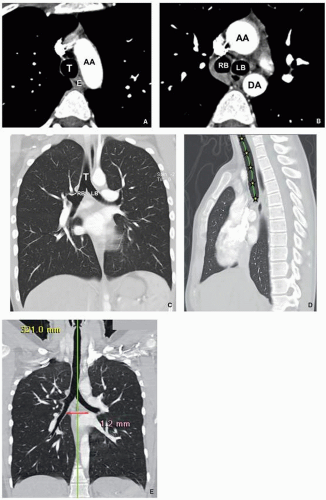

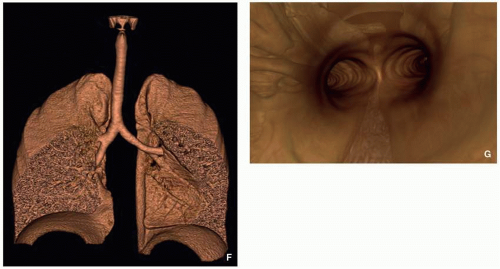

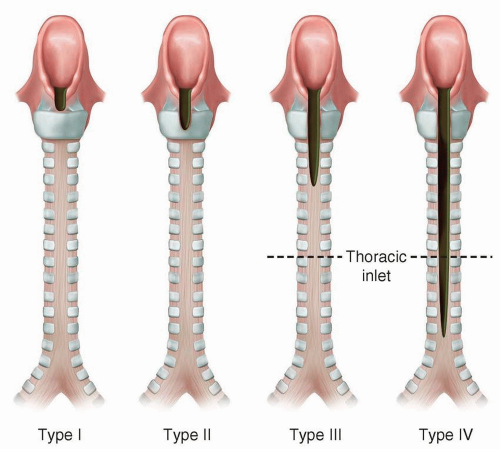

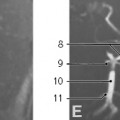

There are four types according to the Benjamin and Inglis classification scheme: Type I is an interarytenoid soft-tissue defect that does not involve the cricoid cartilage; type II extends into the cricoid cartilage; type III extends through the cricoid cartilage and may involve the cervical trachea; and type IV extends into the posterior wall of the thoracic trachea and, potentially, the carina (

Fig. 2.20).

62 Laryngeal cleft has traditionally been considered rare, reportedly representing <0.5% of all congenital larynx anomalies.

63,

64 However, with increasing diagnosis in recent years, the actual prevalence may be higher. There is a slight male predominance. Associations include laryngomalacia; absent tracheal rings; pulmonary agenesis; anomalies of the cardiovascular, genitourinary, and gastrointestinal systems; and syndromes such as Opitz G/BBB, Pallister-Hall, VACTERL, and CHARGE. The clinical presentation may include chronic cough and choking, cyanosis during feeding, aspiration, recurrent pneumonia, respiratory distress, and stridor. Because symptoms are nonspecific and the disorder uncommon, the diagnosis may be delayed.

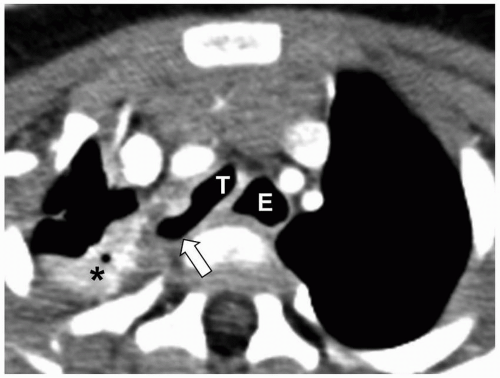

63,

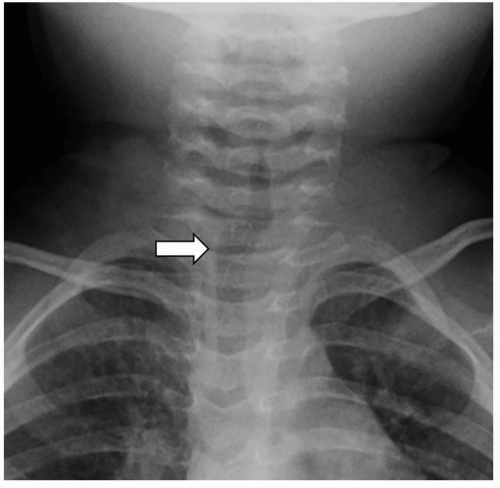

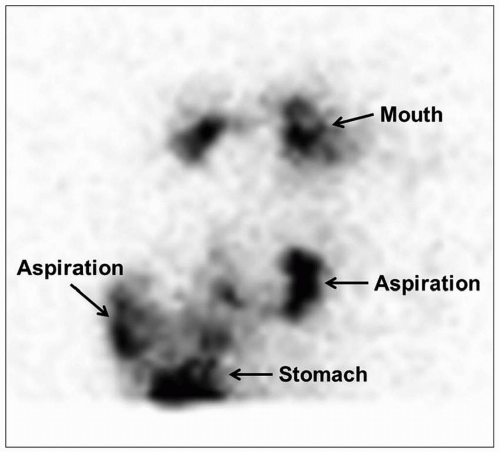

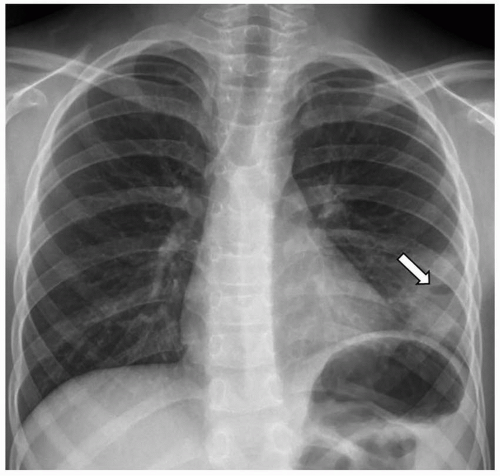

64Direct laryngoscopy with visualization of the interarytenoid area remains the most reliable method of diagnosis. However, a variety of imaging modalities are used in the workup. Chest radiographs may be normal or show findings compatible with chronic aspiration or pneumonia, including consolidation and reticular opacities more often occurring in

the lower lobes (

Fig. 2.21).

63,

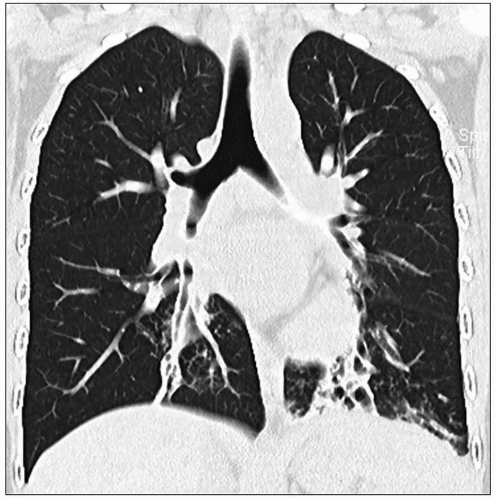

64 Chest CT demonstrates similar findings, but with greater sensitivity and anatomic precision (

Fig. 2.22). Modified barium swallow study is useful for assessing aspiration. Barium swallow study may show passage of contrast into the trachea, potentially leading to misdiagnosis of tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) rather than laryngeal cleft.

63,

64 CT or MRI may occasionally demonstrate the abnormal communication and lack of soft tissue between the trachea and esophagus. An abnormally anterior or intratracheal position of a nasogastric tube is also a clue to the diagnosis. Ultimately, advanced modalities are more often used for assessing associated anomalies.

63,

64Initial conservative medical management includes acidsuppressive treatment for gastroesophageal reflux, change in food texture, and alternative positioning before and after feeding. These strategies help to maintain adequate ventilation and feeding while preventing aspiration. Respiratory distress may require endotracheal intubation, but endoscopic guidance is recommended to mitigate the high risk of tube misplacement. Refractory cases merit surgery. New endoscopic techniques may be adequate for milder cases, while more severe cases require the classical, systematic, external approach (anterior laryngotracheal or lateral pharyngotomy). The overall prognosis depends on the type of cleft, the patient’s pulmonary status, and associated anomalies; early surgery helps mitigate complications of gastroesophageal reflux and aspiration.

64