Larynx: Acute and Chronic Effects of Blunt and Penetrating Trauma

KEY POINTS

- Computed tomography is the imaging examination of choice for evaluating blunt force and penetrating trauma and complications of all forms of upper airway injury.

- Computed tomography is an ideal complement to clinical and endoscopic examinations.

- Swallowing studies are still sometimes useful.

- Acute injury must be diagnosed and treated within 3 to 7 days for optimal outcome.

- The status of the cricoid cartilage is a critical prognostic element.

- Laryngeal injury is sometimes overlooked in multitrauma victims with more obviously life-threatening problems.

The larynx is commonly injured accidentally or iatrogenically. Iatrogenic trauma is discussed in conjunction with subglottic stenosis (Chapter 208). The treatment principles for the injured larynx have been in place for decades and well before the advent of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Treatment has varied little since this earlier reported experience; however, triage, planning, and prognosis are now executed in a more informed context because of diagnostic imaging input.

The imaging appearance of an injured larynx depends directly on the mechanism of injury. Imaging, almost entirely nowadays with CT, shows the extent of injury to the laryngeal skeleton and related tissues. In the late 1970s and into the 1980s CT, significantly advanced our understanding of how the larynx responds to blunt and other forms of trauma.1–3 Imaging with CT, and occasionally other studies, takes its place alongside endoscopy on the critical path for triage of laryngeal injuries to proper management plans.

ANATOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

Applied Anatomy

A thorough knowledge of the following anatomy and anatomic variations of normal in each of the following areas is required for the evaluation of laryngeal trauma. This anatomy is presented in detail with the introductory material on the larynx, hypopharynx, cervical esophagus, and infrahyoid neck in general:

Evaluation of Primary Laryngeal and Hypopharyngeal Injury

Larynx, including the laryngeal skeleton, deep tissues spaces within the larynx, mucosal landmarks, and functional structures within the larynx (Chapter 201)

Larynx, including the laryngeal skeleton, deep tissues spaces within the larynx, mucosal landmarks, and functional structures within the larynx (Chapter 201)

Hypopharynx (Chapter 215)

Hypopharynx (Chapter 215)

Tongue base region and low oropharyngeal wall (Chapter 190)

Tongue base region and low oropharyngeal wall (Chapter 190)

Cervical esophagus, most importantly the esophageal verge junction with the postcricoid portion of the hypopharynx (Chapter 221)

Cervical esophagus, most importantly the esophageal verge junction with the postcricoid portion of the hypopharynx (Chapter 221)

Trachea (Chapter 209)

Trachea (Chapter 209)

Evaluation of Injuries to Extralaryngeal Structures

Visceral compartment of the neck and related fasciae (Chapter 149)

Visceral compartment of the neck and related fasciae (Chapter 149)

Evaluation of Related Vocal Cord Dysfunction and Nerve Injury

Knowledge of the entire course of the vagus and recurrent laryngeal nerves on both sides (Chapter 201)

Knowledge of the entire course of the vagus and recurrent laryngeal nerves on both sides (Chapter 201)

IMAGING APPROACH

Techniques and Relevant Aspects

The neck should always be slightly hyperextended for laryngeal CT. This pulls the larynx higher in the neck, thus reducing artifacts produced by the shoulders. This may not be possible if the neck has been immobilized in an acutely injured patient.

Laryngeal images must be viewed as parallel to the TVCs. This angle is usually selected from a preliminary lateral digital image. In acute trauma patients, angling may impede optimal data acquisition for brain or cervical spine studies, so the axial images may be retrospectively reformatted from a volume set of image files or reconstructed from volume raw data files if the acquisition angle of the gantry is not optimized for the laryngeal anatomy by being parallel to the TVCs. Sections made or viewed oblique relative to the TVC can produce substandard images that lead to interpretative difficulties and possibly treatment mistakes. Skewed image review may lead to a wrong interpretation of the anatomic relationships in the transglottic region that are often critical to medical decision making. Slice thickness (SLT) should be no more than 1 to 3 mm in detailed laryngeal studies. If angled axial reformations or reconstructions are anticipated, then section SLT must be kept between 1 and 2 mm. This will also assure good-quality multiplanar reformation. The field of view of the larynx should be as small as possible to optimize spatial resolution. A second reconstruction with a larger field of view should be included for evaluation of regional anatomy that may also be traumatized. Adequacy of the technique used can be measured by whether it produces artifactfree images with excellent fine detail of the paraglottic space at the level of the TVCs and laryngeal skeletal detail.

In general, these requirements are simply fulfilled on multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) $16 slices by obtaining a volume set of data with nominal SLT of 1.0–1.5 mm and then reconstructing the volume to fulfill the criteria just set forth. An example of protocols applied to MDCT $4 detector rows is summarized in Appendix A.

Intravenous contrast is only selectively used in studies of laryngeal trauma. A compelling reason to use contrast occurs infrequently. This is mainly for studies that are done at least a few days after trauma when secondary infection of the laryngeal skeleton or neck infection due to a false passage is suspected. CT angiography may be added if there is evidence of active bleeding or other cause to suspect a vascular injury as well as an injury of the larynx.

Magnetic resonance (MR) studies, if done, should use receiver coils that are custom designed to study the neck. Small loop or posteriorly placed surface coils meant to study the spine are not adequate. The use of intravenous paramagnetic contrast is individualized, but generally it should not be used. Specific protocols are presented in Appendix B.

Pros and Cons

CT is the primary imaging examination for blunt, penetrating, and iatrogenic trauma as well as for retained foreign bodies. CT is a major advantage for the laryngologist in this regard. A patient with severe head and neck injuries presents no problem for safe and convenient laryngeal imaging at the same time the brain, face, and cervical spine and multiple other systems are evaluated by MDCT at initial intake. This is particularly important in multisystem trauma due to motor vehicle accidents since this is the most common cause of blunt laryngeal trauma.

CT may be used to screen for false passages but cannot be used to exclude such mucosal injury. Swallowing studies are used to screen for false passages as suggested by endoscopic evaluation.

MRI is almost never used for the evaluation of acute trauma and is very infrequently indicated in chronic conditions. It has been used very selectively for chronic traumatic conditions resulting in very unusual circumstances where the prevertebral space or neural elements might be involved in the disease process.

Controversies

There is some debate about whether patients suspected of having false passages should be evaluated with barium or water-soluble contrast. This debate centers on the risk of particulate contrast being deposited in an infected space in the neck versus the risk of the pulmonary toxicity of aspirated water-soluble contrast. In general, even though the contrast is suboptimal for visualization of subtle leaks, water-soluble contrast is used.

SPECIFIC DISEASE/CONDITION

Blunt and Penetrating Laryngeal Trauma and Aspirated Foreign Bodies

Etiology

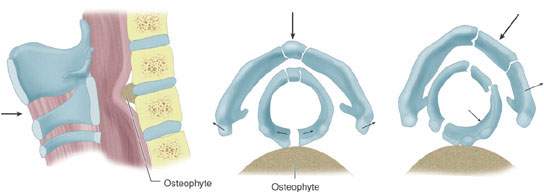

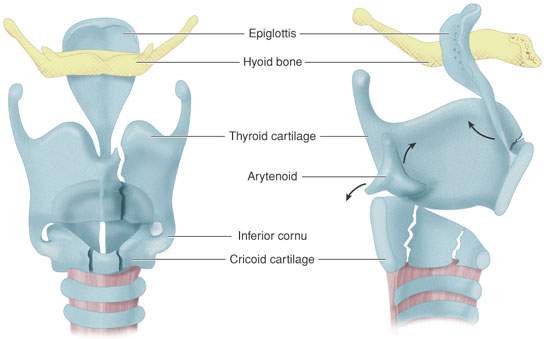

Blunt laryngotracheal trauma most commonly is due to a force applied from anterior to posterior. The most common impacts are between the neck and a dashboard, a punch of some sort to the neck, or a “clothesline” type of mechanism of injury. The final common pathway in these events is compression of the larynx between the source of the force and cervical spine (Figs. 207.1–207.5). The amount and vector of the applied force, area impacted, and contour of the offending object all contribute to the extent of injury. There are other factors that influence the pattern of injury as well (Figs. 207.1–207.5).

False passages and their complications that might accompany laryngeal blunt force trauma typically affect the hypopharynx rather than the larynx and are also discussed in conjunction with hypopharyngeal injuries (Figs. 207.5C and 207.6).

Penetrating injuries are most frequently related to stab and gunshot wounds. These will usually be evaluated in conjunction with more potential serious injuries to the brachiocephalic vessels in penetrating neck injuries.

Very severe blunt trauma and crush injuries may lead to a combination of findings and considerations seen in both blunt and penetrating mechanisms (Fig. 207.7).

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Blunt laryngeal trauma is a sporadic occurrence that mainly is associated with motor vehicle accidents. Clothesline-type injuries are more associated with motorcycle, all-terrain vehicle, and bicycle accidents. Assaults and fights make up the bulk of other blunt-force trauma to the neck. Blunt and penetrating insults may occur with the same incident. Penetrating injuries are relatively uncommon. Retained foreign bodies are usually in the pharynx rather than the larynx.

Clinical Presentation

Blunt-force and penetrating injuries of the larynx and trachea may compromise critical functions. Airway maintenance is always the primary concern. Once the airway is secured, therapy is focused on preserving other glottic function, including a normal voice and assuring swallowing without aspiration. Acute injuries require a rapid examination that is accurate and free of potential added morbidity.

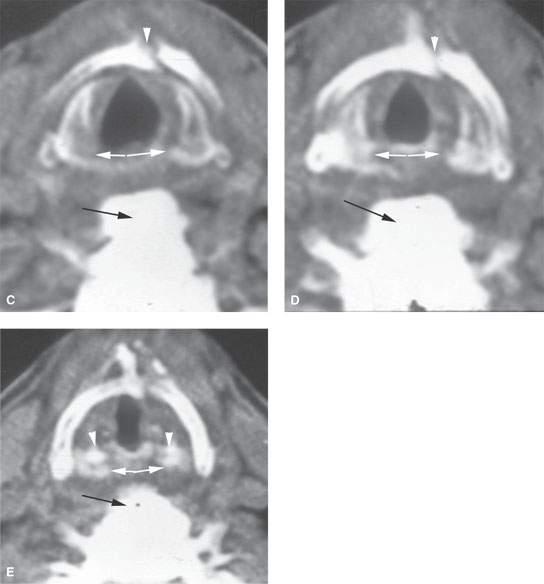

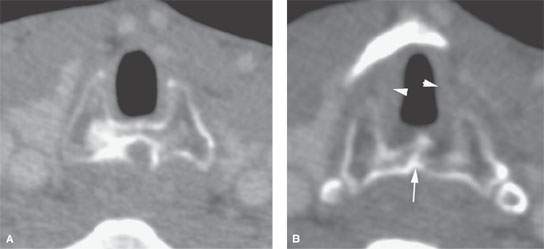

FIGURE 207.1. A: Diagram of mechanisms of laryngeal injury showing that the primary force involved is one directed at the larynx, possibly compressing the larynx between the offending force and the cervical spine. B: Diagram showing force of injury which, rather than being applied in a straight front to back vector as in (A), may come obliquely, resulting in alternative patterns of injury to the cricoid, thyroid, and epiglottic cartilages. These views show how the epiglottis might be avulsed at the thyroepiglottic ligament attachment; the arytenoid cartilage may be displaced anteriorly or posteriorly. They also show the trends of paramedian thyroid lamina fracture and how the cricoid might be fractured along its anterior and lateral aspects as well as being split posteriorly as seen in (A). C–E: Computed tomography study of a patient demonstrating a direct anterior to posterior compressive force due to strangulation. The images show that the larynx was impaled on the large osteophyte (black arrow), causing the cricoid cartilage to be split posteriorly and separated (white arrows). The thyroid cartilage shows a comminuted paramedian fracture (white arrowheads in C and D). The patient was aphonic because the arytenoid cartilages (arrowheads in E) followed their respective cricoarytenoid joints laterally and the vocal cords could not come together in the midline.

Clinical evaluation may suggest laryngeal injury; however, this possibility may be overlooked when other extensive head and face injuries are present in the absence of life-threatening airway obstruction. Swelling of the cervical soft tissues can hide gross disruption of the normal laryngeal skeleton from palpation (Fig. 207.3). Failure to acutely establish the extent of laryngeal injury can lead to a laryngeal stenosis that has typically proven more difficult to manage at a later time. Delayed or lack of definitive treatment can lead to a less satisfactory outcome (Figs. 207.8–207.10).

Classification systems for laryngotracheal complex injuries have been suggested for many years. Injury may involve one or more of these sites, but such classification remains a useful structure for discussing the diagnosis and management of blunt trauma. This clinical classification will be used in the following discussion of diagnostic imaging:

- Acute

- Soft tissue

- Subglottic

- Glottic

- Supraglottic

- Soft tissue

- Chronic stenosis

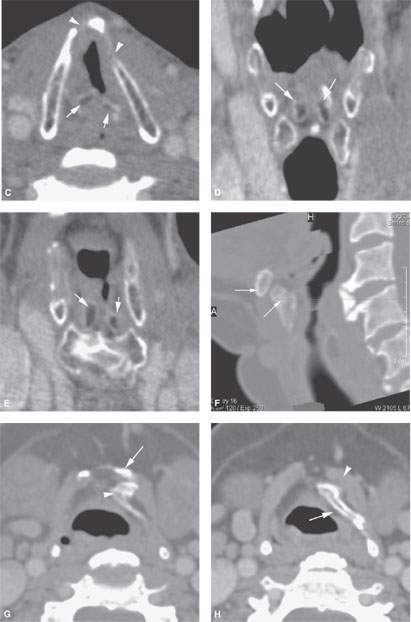

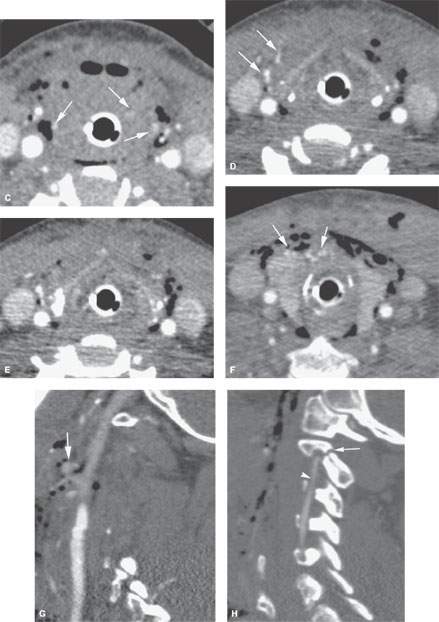

FIGURE 207.2. A patient also suffering a strangling injury as the patient seen in Figure 207.1C,D. In this patient, the injuries were not repaired, leading to chronic scarring, deformity, and related laryngeal dysfunction. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography study was done. In (A), a section through the subglottis shows the healed fracture of the posterior cricoid lamina and the secondarily narrowed subglottis. In (B), in the mid subglottis, the healed cricoid fracture (arrow) continues to narrow the subglottic airway (arrowheads). In (C), the axial sections through the true vocal cords show healed paramedian deformity of the thyroid cartilages. Note that the arytenoids are both displaced (arrows) and appear to be much more medial than usual due to scarring at the posterior commissure. The coronal reformation in (D) shows the arytenoids near the midline, well medial along the surface of the cricoid cartilage. This abnormally medial position of the arytenoids is seen again in (E). The sagittal reformation in (F) shows the deformity of the thyroid cartilage and its abnormal relationship to the hyoid bone (arrows). The compressive forces squeezed the larynx between the object used for the strangulation and the large osteophytes present at that level. In (G), the deformed hyoid bone (arrow) and thyroid lamina can be seen in a grossly abnormal relationship further demonstrated in (H) as deformity of the thyroid lamina, reduction in paraglottic fat due to scarring (arrow), and the deformity and scarring of the infrahyoid strap muscles (arrowhead) on the left. (NOTE: All of these findings combined to produce significant glottic dysfunction, including a very poor voice quality and aspiration. Failure to repair this injury initially led to the inability to fully restore glottic function eventually.)

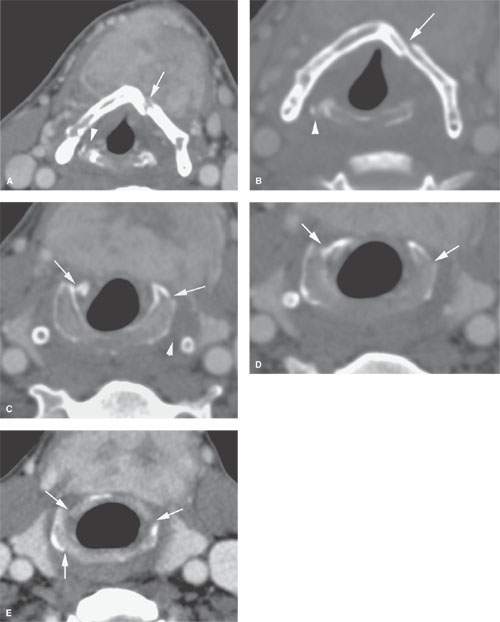

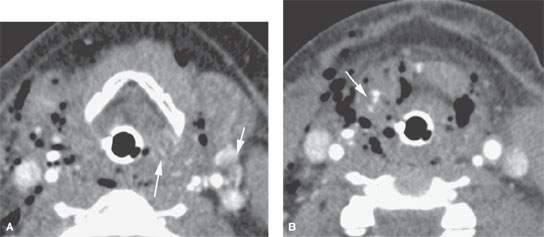

FIGURE 207.3. Contrast enhanced computed tomography study of a patient suffering injury to the neck in a car accident. The patient had extensive swelling in the neck impeding the physical examination of the larynx. In (A), the large neck hematoma due to a ruptured thyroid overlies the larynx. There is a left paramedian thyroid lamina fracture (arrow) and a likely dislocated and possibly fractured arytenoid cartilage on the right (arrowhead). In (B), a close-up view for bone detail shows the minimally displaced thyroid lamina fracture (arrow) and the posteriorly dislocated arytenoid (arrowhead). In (C), there are minimally displaced fractures of the cricoid arches (arrows) seen again in (D) and continuing inferiorly in (E). (NOTE: This case illustrates how extensive soft tissue swelling might interfere with clinical evaluation of the larynx and the type of information useful in determining the approach to laryngeal skeleton repair.)

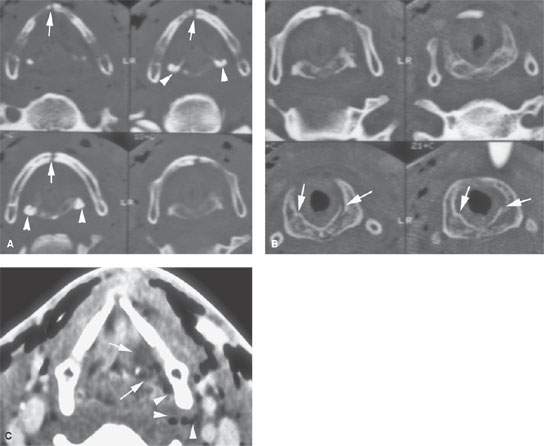

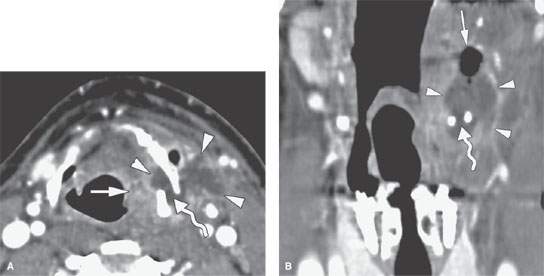

FIGURE 207.5. A series of images from a contrast-enhanced computed tomography study in a patient experiencing neck trauma due to a motor vehicle accident. The images seen in (A) and (B) are from the false cord level to the low subglottis in sequence and show the type of injury that matches well with Figure 207.1. There is a thyroid lamina fracture anteriorly (arrows in A) and evidence of arytenoid cartilage malpositioning (arrowheads). In (B), the arrows show minimally displaced cricoid cartilage fractures but considerable amount of soft tissue swelling in the subglottis, which resulted in a tracheostomy. This patient was treated conservatively. The abnormal position of the arytenoids was eventually shown to be due to extensive swelling and not true arytenoid dislocation. In (C), there is extensive swelling along the posterior aspect of the left false vocal fold (arrows) and some gas tracking in the soft tissue from the pyriform sinus (arrowheads). This suggests the presence of a false passage, which subsequently was confirmed at endoscopy. (NOTE: This study shows how the degree of soft tissue injury can be separated from the degree of laryngeal skeletal injury for medical decision making. In this case, the airway had to be managed because of the acute hemorrhage and subglottic narrowing, and the false passage was confirmed. The laryngeal skeletal injuries were treated conservatively and healed without residual problems.)

FIGURE 207.4. Axial computed tomography images in a patient suffering dyspnea and dysphonia after a motor vehicle accident. A: At the glottic level, there a displaced fracture of the thyroid cartilage (arrow) and a soft tissue tear (arrowheads) with partial avulsion of left true vocal cord (asterisk). B: At the subglottic level, there are several fractures of the cricoid arch (arrows). The associated soft tissue thickening causes narrowing of the subglottic lumen. Several air bubbles are present in the soft tissues of the neck (arrowheads).

FIGURE 207.6. A patient who developed painful laryngeal swelling a few days after being victim of a strangulation attempt. A: Computed tomography image showing a fracture of the hyoid bone (curved arrow). An abscess developed within and outside of the laryngeal skeleton (arrowheads) centered at the fracture site presumably due to a mucosal perforation of the pharyngeal wall, which appears thickened and shows inhomogeneous enhancement (arrow). B: Coronal reformatting imaging demonstrates hyoid fracture (curved arrow) and gas (arrow) containing abscess (arrowheads). (NOTE: During surgical drainage of the abscess, the hyoid fracture was confirmed; a small laceration of the pharyngeal wall was also detected.)

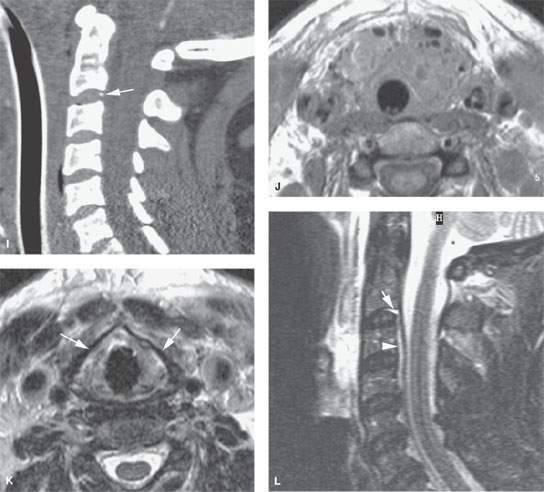

FIGURE 207.7. A patient with a very severe injury to the neck due to a high-energy motor vehicle accident. The contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) study was done to evaluate the extent of neck injury. A–F: Images showing the laryngeal skeleton to be grossly intact. There is generalized severe swelling throughout the neck with free air in the soft tissues. In addition, there are numerous areas of contrast paddling (arrows) in the laryngeal and pharyngeal soft tissues consistent with vascular injury. The study also shows gas tracking from the lumen of the larynx directly into the soft tissues. The findings were considered overall to be consistent with a very significant crush injury to the larynx, but the laryngeal skeleton remaining intact and the injury being predominately soft tissue. G: CT angiogram showing evidence of vascular injury with puddling of contrast (arrow). H: One of several present cervical spine injuries (arrow) as well as a traumatic dissection of the vertebral artery (arrowhead). I: An avulsion fracture suggesting ligament injury at the C3 level was suspected. J–L: Magnetic resonance (MR) study on this patient done mainly to assess potential neurologic injury. In (J), diffuse soft tissue swelling related to the accumulating hematoma and soft tissue injury within the visceral compartment is present. The gas can be seen as signal voids but is less apparent than on CT. In (K), the T2-weighted (T2W) image shows the surprisingly normal-appearing thyroid lamina somewhat better than that seen on the CT images in (D) and (E). In (L), the sagittal T2W image shows the abnormal signal related to the ligament injury at C2-3 as well as injury to the disk. There is related small epidural collection of fluid or blood beneath the anterior longitudinal ligament. (NOTE: This study shows how effectively focused imaging with CT and necessary MR may triage the multiple problems that may occur in multisystem neck trauma.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree