Etiology

Leukemias are a group of malignancies in which abnormal cells, usually abnormal white blood cells (leukocytes), are produced in the bone marrow. Leukemias may be classified as myeloid, also known as myelogenous or myeloblastic, or lymphoid, also known as lymphocytic or lymphoblastic, depending on the types of abnormal cells that are produced. In myeloid leukemias, myeloid stem cells, which normally develop into erythrocytes, platelets, and granulocytes or monocytes, are affected; in lymphoid leukemias, lymphoid stem cells, which normally develop into lymphocytes, are affected. Leukemias are classified as acute or chronic according to cellular maturity; immature, poorly differentiated cells (blast cells) predominate in acute leukemias, whereas chronic leukemias have more mature cells. The four major leukemia types are acute myeloid leukemia (AML), chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL) is now grouped with CLL (CLL/SLL) because they are recognized as the same disease entity; differentiation is based on peripheral blood absolute lymphocyte count. CML leads to the formation of the BCR-ABL1 oncogene. The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of leukemia has been recently revised to incorporate new clinical, morphologic, immunophenotypic, genetic, and prognostic data.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

AML is much more common in adults than children and accounts for approximately 80% of acute leukemias in adults. Median age at diagnosis is 67 years, and males are more commonly affected than females. Among the four major leukemia types, AML has the worst prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of approximately 20%. CML is primarily a disease of adults and accounts for approximately 15% of leukemias in the adult population. Median age at presentation is 44 to 55 years. With the advent of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy, the annual mortality in CML has decreased to 1% to 2%, and consequently, its prevalence in the United States has increased. ALL is the most common leukemia in young children, with a peak incidence between ages 2 and 5 years; ALL can also affect older adults age 65 years and older. CLL, the most frequent type of leukemia in the Western Hemisphere, usually affects adults, most commonly older than 65 years. The median survival of patients with CLL is 10 years, although life expectancy can range from about 2 to 3 years to 2 decades based on clinical stage; most patients have an indolent clinical course with prolonged survival.

Risk factors for the development of leukemia include previous exposure to ionizing radiation or chemical agents, prior treatment with certain chemotherapeutic drugs, certain viral infections, chromosomal translocations, immunodeficiency disorders, chronic myeloproliferative disorders, and certain chromosomal disorders.

Clinical Presentation

Clinical manifestations of leukemia are due to either suppression of normal marrow function or organ infiltration by leukemic cells. Suppression of normal marrow function results in anemia, thrombocytopenia, and leukopenia, whereas organ infiltration can lead to lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, and skeletal pain.

Common presenting symptoms of AML are usually related to anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia and may include fatigue, infection, or bleeding. Common presenting symptoms of ALL include lymphadenopathy, skeletal pain, bleeding, or fever. Patients with chronic leukemias are frequently asymptomatic at diagnosis. Between 20% and 50% of patients with CML are asymptomatic and are diagnosed by routine tests. Common presenting symptoms include fatigue, bleeding, weight loss, abdominal fullness, and splenomegaly. CLL patients often have lymphadenopathy that may involve the cervical, axillary, or inguinal regions. The majority of patients with CLL have an indolent course, but some patients with aggressive disease can have frequent relapses. Richter transformation occurs in patients with CLL and is a rare clinical entity associated with poor outcome defined by the development of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma or, much less frequently, classic Hodgkin lymphoma. The incidence rate of Richter transformation is 0.5% per year of observation.

Clinical manifestations of leukemic pulmonary infiltration are nonspecific and include cough, dyspnea, and fever. Diagnosis requires bronchoalveolar lavage or lung biopsy.

Pathophysiology

All blood cells (red blood cells, platelets, and white blood cells) originate from hematopoietic stem cells. In the leukemias malignant transformation usually occurs at the pluripotent stem cell level. As a result of abnormal proliferation, clonal expansion, and diminished apoptosis, normal blood elements are replaced with malignant leukemic cells. Bone marrow failure—resulting from both marrow crowding by abnormal cells and inadequate production of normal marrow elements—and organ infiltration ensue.

Myeloid sarcoma, in the 2016 WHO classification, represents a unique presentation of any subtype of AML. It is defined as a tumor mass consisting of myeloid blasts, with or without maturation, occurring at an anatomic site other than the bone marrow. It may present de novo, with concurrent AML, as extramedullary relapse of AML, or as progression of a prior myeloproliferative neoplasm. It was formerly known as granulocytic sarcoma, chloroma, or myeloblastoma. The term chloroma is derived from the characteristic green color resulting from the high levels of the intracellular porphyrin-bearing enzyme myeloperoxidase. Bone (subperiosteal) and perineural involvement is common, whereas thoracic involvement is uncommon.

Leukemic pulmonary infiltration is defined as extravascular collections of leukemic cells in regions of lung parenchyma not demonstrating other apparent causes for their presence (e.g., infection, hemorrhage, or venous congestion). Leukemic pulmonary infiltration has been found at autopsy in a substantial percentage (>25%) of patients with leukemia.

Other conditions of lung involvement seen in myeloid leukemias include leukostasis, leukemic cell lysis pneumopathy, and hyperleukocytic reaction. Pulmonary leukostasis is a condition that results from obstruction of pulmonary capillaries, arterioles, and small arteries by leukemic cells. Leukostasis occurs most commonly in AML and less commonly in patients with CML in blast crisis. Total white blood cell count is usually between 100,000 and 500,000/mm. Leukemic cell lysis pneumopathy, a condition characterized by severe hypoxemia and diffuse pulmonary opacities that occurs within 48 hours after the initiation of chemotherapy in patients with high leukocyte counts, can manifest as pulmonary hemorrhage, edema, and diffuse alveolar damage. Hyperleukocytic reaction is due to an increase in blast counts leading to intravascular accumulation of neoplastic cells, causing thrombi and alveolar hemorrhage.

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (PAP), a rare disorder with accumulation of excess surfactant within pulmonary alveoli resulting in cough and dyspnea, can be seen in association with hematologic malignancies. CML is the most commonly associated leukemia in reported cases of secondary PAP, although association with ALL and CLL have also been reported.

In an autopsy review, pleural involvement was found in 15% of patients with leukemia. In another review of autopsy findings in 495 patients with leukemia, pleural involvement was found to occur most commonly with ALL, occurring in 27% of patients with ALL. Malignant pleural effusions can be seen at any time with acute leukemias but tend to occur in advanced disease in chronic leukemia.

The pericardium, myocardium, and endocardium may be infiltrated by leukemia. At autopsy, rates of cardiac involvement by leukemia range from 11% to 37%. Leukemic cardiac involvement is frequently clinically silent.

Manifestations of the Disease

Intrathoracic imaging manifestations of leukemia include involvement of the mediastinum, lungs, pleura, heart, and axillae.

Mediastinum

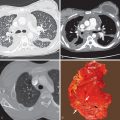

Mediastinal lymphadenopathy is relatively common in patients with CLL and ALL, occurring in 25% of patients with CLL ( Fig. 26.1 ) and 10% to 20% of patients with ALL. Hilar lymphadenopathy is less common. Patients with ALL may present with a large symptomatic anterior mediastinal mass. Mediastinal lymphadenopathy is less common in cases of AML or CML, occurring in 5% of these patients.

Myeloid sarcoma may manifest as a focal mediastinal mass ( Fig. 26.2 ), lymphadenopathy, or diffuse infiltration of mediastinal tissues. Other less commonly affected sites include the hila, pleura, lungs, and pericardium.

Lung

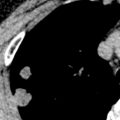

In most cases pulmonary leukemic infiltration is not evident radiographically. When evident it usually manifests as a bilateral reticular pattern with septal lines resembling interstitial edema or lymphangitic carcinomatosis. Nodules and focal homogeneous opacities may also be seen.

On CT leukemic pulmonary infiltration usually manifests with smooth and/or nodular thickening of the interlobular septa and bronchovascular bundles as a result of the predilection of leukemic cells to infiltrate the pulmonary lymphatics. Small nodules are also a common feature, although not usually the dominant finding. Nodule distribution may be peribronchovascular, centrilobular, or random. Areas of ground-glass attenuation and consolidation can also be seen, and the consolidation may be predominantly peribronchial in location ( Fig. 26.3 ).

Pulmonary abnormalities on imaging are only rarely due to leukemic infiltration alone; coexisting abnormalities may include pneumonia, edema, hemorrhage, and drug-induced injury.

Imaging in patients with leukostasis may be normal or resemble interstitial or alveolar edema. Leukemic cell lysis and hyperleukocytic reaction result in nonspecific bilateral consolidation.

Imaging findings of secondary PAP are similar to findings in the idiopathic form of the disease, consisting of geographic ground-glass opacities with or without septal thickening.

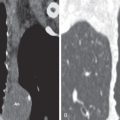

Pleura

Pleural leukemic involvement can manifest on imaging as (1) pleural effusion, (2) pleural masses or pleural thickening, or (3) a combination of pleural effusion and pleural masses/pleural thickening ( Fig. 26.4 ).