Clinical Presentation

The patient is a 50-year-old female who presented with acute neck and shoulder pain. Over the last 2 weeks, she has noticed progressive, constant pain in the anterior midline aspect of her upper neck. She characterizes the pain as a dull ache. She has been having episodes of sharp neck pain that can be brought on by turning her head toward the right or the left or looking up. She notes intermittent, mild radiation of the pain into both of her shoulders. She describes some pain with swallowing. She does not confirm any weakness, numbness, or tingling in her arms, hands, or lower extremities. She has had no fever, chills, night sweats, weight loss, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, changes in vision, syncope, or near syncope.

Imaging Presentation

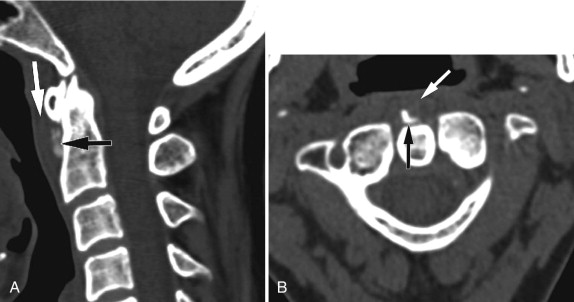

Sagittal and axial computed tomography (CT) images of the upper cervical spine reveal a small amorphic calcific density ventral to the dens and inferior to the anterior arch of C1. There is associated very mild prevertebral soft tissue swelling. These imaging characteristics and the location of this finding are pathognomonic of longus colli tendinitis ( Fig. 44-1 ) .

Discussion

Acute calcific tendinitis is an inflammatory condition caused by deposition of calcium hydroxyapatite crystals in the longus colli muscle. Acute calcific tendinitis, also known as retropharyngeal calcific tendinitis , acute calcific prevertebral tendinitis, or longus colli tendinitis , is a fairly uncommon condition. It is an under-recognized cause of acute cervical pain produced by inflammation of the longus colli muscle. Patient may present with neck pain, dysphagia, or odynophagia and low grade fever. Laboratory evaluation may demonstrate a mildly elevated white blood cell count and a mildly elevated sedimentation rate.

Acute calcific tendinitis was first described by Hartley in 1964. The etiology of calcium hydroxyapatite crystal deposition is unknown; however, some postulate that repetitive trauma, recent injury, tissue necrosis, or ischemia may play a factor. It is thought that the crystals, once deposited within the longus colli muscle, start a foreign body–like inflammatory reaction.

The primary differential diagnosis to exclude is retropharyngeal abscess. A retropharyngeal abscess is most likely to occur in infants, although it can occur in adults with the main cause being pharyngitis, tonsillitis, or a foreign body in the pharynx. Other distinguishing features of acute calcific tendinitis are the lack of ring enhancement of the effusion, the lack of associated adenopathy, and the symmetric expansion of the prevertebral/retropharyngeal space by the effusion. The pathognomonic finding of acute calcific tendinitis is the amorphic calcification anterior to C1-2 in the superior oblique muscle where the longus colli tendon inserts.

Imaging Features

The principle radiographic findings of acute calcific tendinitis are prevertebral soft tissue swelling, typically extending from C1-C4, and a focus of amorphic calcification anterior to C1-2. The soft tissue swelling can be due either to an effusion or edema. Acute calcific tendinitis must be distinguished from a retropharyngeal abscess because they both can manifest similarly—swelling of the retropharyngeal wall, cervical pain, neck stiffness, sore throat, and fever—but they have very different treatments. The lack of enhancement surrounding the effusion is helpful because enhancement is not seen around the effusion in acute calcific tendinitis and is seen with abscess. The effusion also usually causes uniform expansion of the retropharyngeal space and may dissect through the fascia in a coronal plane. Retropharyngeal lymphadenopathy is associated with abscess and not with acute calcific tendonitis. The amorphic calcification anterior to C1-2, where the superior oblique muscle of the longus colli tendon inserts, is pathognomonic for acute calcific tendinitis. Plain film radiography can demonstrate the amorphic calcification. Computed tomography (CT) with its superior spatial resolution demonstrates the amorphic calcification definitively as well as the effusion and/or edema and is the procedure of choice (see Fig. 44-1 ). Intravenous contrast should be given if there is clinical concern of abscess. Magnetic resonance (MR) imaging is usually not necessary to make the diagnosis, but can sometimes demonstrate increased T2 or short tau inversion recovery (STIR) signal intensity in the adjacent vertebra secondary to marrow reactive change as well as increased T2/STIR signal in the prevertebral soft tissues from soft tissue edema ( Fig. 44-2 ) .