Lower Extremity Venous Studies

J. Christian Fox

Negean Vandordaklou

INTRODUCTION

The possibility of a lower extremity deep venous thrombosis (DVT) is a frequent clinical concern in emergency medicine, arising in patients with varied presentations, from painless leg swelling to impending cardiopulmonary arrest. DVT and pulmonary embolus (PE) can be difficult to diagnose and carry significant morbidity and mortality. Physical exam findings have a low sensitivity for the detection of DVT (1). Historical factors can aid in risk stratification, but not ultimate diagnosis (2). Although there are numerous diagnostic possibilities for patients in whom a DVT is suspected, venous compression ultrasonography is the most practical test for the emergency department (ED) setting.

In many institutions, consultative vascular studies are not available outside of regular business hours (3). Given this lack of availability, many clinical decision rules combining risk factor assessment and the use of a quantitative D-dimer assay have been proposed (4). These protocols decrease the need for vascular studies in low-risk patients, but still leave many patients requiring a service that is often not available. When a DVT is suspected, emergency physicians are often faced with three options: admit the patient, hold the patient in the ED awaiting the availability of venous studies, or discharge the patient after anticoagulation in the ED with arrangement for an outpatient study as soon as possible. This is especially troublesome for patients without primary care physicians, patients presenting early in the weekend, or patients without reliable follow-up. In response to these many concerns, emergency physicians began performing their own bedside examinations of the lower extremity venous system to evaluate for the presence of DVT. Although traditional venous compression ultrasonography is thorough and time-consuming, a limited approach that is more practical for emergency medicine practice can be applied. Poppiti et al. demonstrated that limited venous ultrasound can be done with a dramatic reduction in the usual time required for a complete consultative exam, taking 5.5 minutes for a targeted emergency ultrasound compared with 37 minutes for the complete vascular exam of the lower extremity (5,6). It has been shown that emergency physicians can accurately detect DVT on focused ultrasound (3,7, 8, 9, 10, 11). Another study showed that 2-point ultrasound performed by emergency physicians had sensitivity and specificity of 100% and 99% respectively when compared to radiology-performed ultrasounds (12). Similarly, Kline et al. found that emergency sonographers who had done at least five prior studies achieved sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 98% (13). Bernardi et al. compared a 2-point ultrasound in combination with a D-dimer assay to whole leg ultrasound. The purpose of this study was to limit the number of patients who had to return for a repeat DVT ultrasound in 1 week after a negative emergency physician performed ultrasound, which is currently common practice. If patients had a negative 2-point ultrasound and negative D-dimer, they did not have to return for a repeat ultrasound; however, if they had a negative 2-point ultrasound and a positive D-dimer, they were advised to return in 5 to 7 days for a repeat ultrasound. This method proved to be highly accurate when compared to whole leg ultrasound (14). Limited emergency ultrasound is thus both accurate and fast enough to be practical for typical emergency medicine practice (3,8).

PEDIATRIC CONSIDERATIONS: Although DVT’s in the pediatric population are often rare, they still do occur. They are mostly related to central venous catheter complications or secondary to underlying diseases such as malignancy or genetic coagulopathies. Nonetheless, the emergency physician can successfully identify DVT’s in this population using the same techniques as in the adult population (15).

PEDIATRIC CONSIDERATIONS: Although DVT’s in the pediatric population are often rare, they still do occur. They are mostly related to central venous catheter complications or secondary to underlying diseases such as malignancy or genetic coagulopathies. Nonetheless, the emergency physician can successfully identify DVT’s in this population using the same techniques as in the adult population (15).

CLINICAL APPLICATIONS

Lower extremity venous compression ultrasonography is indicated any time there is a suspicion of a lower extremity DVT. In terms of clinical presentation, leg pain, leg swelling, or symptoms concerning for PE may prompt a clinician to proceed with the exam. There are no absolute contraindications to this noninvasive exam.

IMAGE ACQUISITION

The bedside exam has primary and secondary components. The primary component visualizes the venous structures and detects gray-scale compressibility. The literature suggests that only the primary component can be adequately relied upon for confirming the presence or absence of a DVT (16,17). Lack of compressibility defines a DVT. The secondary component involves the use of Doppler to evaluate for abnormalities in flow. The Doppler exam is an adjunct measure of lesser importance. Note that the diagnosis of DVT does not rest with direct visualization of thrombus within the lumen.

Primary Component

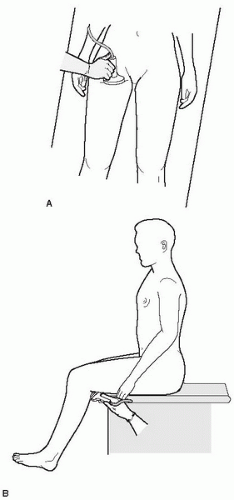

Lower extremity studies are best performed with a high-resolution linear transducer with a frequency of 5 to 10 MHz. Use of higher frequency will give images with better resolution, but lower frequency may be needed in larger patients. Depth should be adjusted based on the physical characteristics of the patient. There are several options for patient positioning, the choice of which will vary with the patient’s clinical condition, body habitus, and physician choice. Generally, the patient is supine. If the patient’s hemodynamic status will allow it, placing the patient in 35 to 40 degrees of reverse Trendelenburg (head up) will increase venous distention and aid in visualization. Also, the patient’s leg can be slightly flexed at the knee and hip, and the hip externally rotated to ease visualization of the vessels (Figs. 17.1 and 17.2).

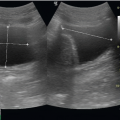

Begin the exam in the region of the common femoral vein, in the transverse plane just distal to the inguinal ligament (Fig. 17.3). Gel should be applied to the transducer or along the course of the vessel. The transverse view is first used to locate the vessel and to evaluate for compression. Once a good transverse view of both the common femoral vein and the artery is obtained (Fig. 17.4), apply direct pressure. In a normal exam, complete coaptation of the vein occurs with pressure (Figs. 17.5 and 17.6;  VIDEO 17.1). In cases in which the vein does not appear to completely compress, there are two main possibilities: (1) presence of a clot, or (2) inadequate pressure on the transducer. Adequate pressure has been applied to the vein when one can observe the artery being deformed by the pressure (Fig. 17.7;

VIDEO 17.1). In cases in which the vein does not appear to completely compress, there are two main possibilities: (1) presence of a clot, or (2) inadequate pressure on the transducer. Adequate pressure has been applied to the vein when one can observe the artery being deformed by the pressure (Fig. 17.7;  VIDEO 17.2). Next, proceed distally and medially, following the course of the vessel (Fig. 17.2). In general, visualization of the common femoral vein should continue in 1-cm increments until the vein descends into the adductor canal, generally about two-thirds down the thigh.

VIDEO 17.2). Next, proceed distally and medially, following the course of the vessel (Fig. 17.2). In general, visualization of the common femoral vein should continue in 1-cm increments until the vein descends into the adductor canal, generally about two-thirds down the thigh.

VIDEO 17.1). In cases in which the vein does not appear to completely compress, there are two main possibilities: (1) presence of a clot, or (2) inadequate pressure on the transducer. Adequate pressure has been applied to the vein when one can observe the artery being deformed by the pressure (Fig. 17.7;

VIDEO 17.1). In cases in which the vein does not appear to completely compress, there are two main possibilities: (1) presence of a clot, or (2) inadequate pressure on the transducer. Adequate pressure has been applied to the vein when one can observe the artery being deformed by the pressure (Fig. 17.7;  VIDEO 17.2). Next, proceed distally and medially, following the course of the vessel (Fig. 17.2). In general, visualization of the common femoral vein should continue in 1-cm increments until the vein descends into the adductor canal, generally about two-thirds down the thigh.

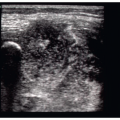

VIDEO 17.2). Next, proceed distally and medially, following the course of the vessel (Fig. 17.2). In general, visualization of the common femoral vein should continue in 1-cm increments until the vein descends into the adductor canal, generally about two-thirds down the thigh.Now begin evaluation of the popliteal region. If possible, have the patient dangle his/her leg off the bed to improve access to the region (Figs. 17.1B and 17.8). Apply gel to the transducer or the skin surface at the popliteal fossa. Visualize the popliteal artery and vein in the transverse view, noting that the vein is more superficial than the artery (Fig. 17.9;  VIDEO 17.3). The rhyme “the vein comes to the top in the pop” may be helpful to remember this. Then proceed with compression in 1-cm increments throughout the popliteal fossa until the division of the popliteal vein (Fig. 17.10). The popliteal vein requires significantly less pressure than the common femoral vein, and in some

VIDEO 17.3). The rhyme “the vein comes to the top in the pop” may be helpful to remember this. Then proceed with compression in 1-cm increments throughout the popliteal fossa until the division of the popliteal vein (Fig. 17.10). The popliteal vein requires significantly less pressure than the common femoral vein, and in some

patients even the pressure from the transducer on the skin may be enough to collapse the vessel.

VIDEO 17.3). The rhyme “the vein comes to the top in the pop” may be helpful to remember this. Then proceed with compression in 1-cm increments throughout the popliteal fossa until the division of the popliteal vein (Fig. 17.10). The popliteal vein requires significantly less pressure than the common femoral vein, and in some

VIDEO 17.3). The rhyme “the vein comes to the top in the pop” may be helpful to remember this. Then proceed with compression in 1-cm increments throughout the popliteal fossa until the division of the popliteal vein (Fig. 17.10). The popliteal vein requires significantly less pressure than the common femoral vein, and in some patients even the pressure from the transducer on the skin may be enough to collapse the vessel.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree