Abdominal Procedures

Gregory R. Bell

INTRODUCTION

Ultrasound is a valuable tool when performing procedures on the abdomen. Ultrasound guidance improves the ease and efficiency of procedures and increases the likelihood of successful completion (1). Using ultrasound to guide procedures lowers the risk of complications compared to the traditional method of using anatomic landmarks (2). This chapter will discuss techniques of using ultrasound to guide common procedures on the abdomen, including paracentesis, hernia reduction, and estimation of bladder volume.

PARACENTESIS

Clinical Indications

There are three indications for ultrasound-guided paracentesis:

To obtain fluid for analysis to establish the etiology, primarily for patients with new onset ascites. Most cases of new onset ascites are due to liver cirrhosis (over 75%), although malignancy, congestive heart failure, and pancreatitis may also be responsible (3).

To obtain fluid for culture, to rule out infection as a cause of worsening ascites, abdominal pain, and/or fever.

To provide symptomatic relief for patients with tense ascites, particularly when it causes respiratory embarrassment.

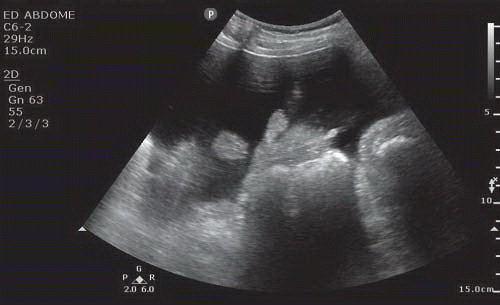

Fluid within the peritoneal cavity is difficult to appreciate using physical exam techniques. The exam maneuvers commonly used, including fluid wave and shifting dullness, are inaccurate and may provide the clinician a false impression of ascites. This false positive conclusion may increase the risk of performing an unnecessary paracentesis, and therefore the potential for invasive complications (4). With ultrasound guidance, the anechoic ascites is clearly seen juxtaposed with the echogenic abdominal organs and abdominal wall (Fig. 13.1). Volumes as low as 100 mL can reportedly be detected with ultrasound (5).

Image Acquisition

Scanning for a paracentesis site will usually require two transducers, depending on the abundance or paucity of

ascitic fluid. A 3 to 5 MHz curvilinear or phased array probe is the best choice for determining the site for catheter placement. Scanning with this probe provides a broad view for the abdominal contents and offers a quick assessment of the presence of fluid. When ascitic fluid is present, one can see where it has accumulated. The other suggested probe to use during paracentesis is a 5 to 10 MHz linear probe. Its purpose is to guide needle placement. This probe is especially important if the volume of ascites is limited, thus creating a small target for fluid aspiration. All imaging is performed using the brightness or B-mode.

ascitic fluid. A 3 to 5 MHz curvilinear or phased array probe is the best choice for determining the site for catheter placement. Scanning with this probe provides a broad view for the abdominal contents and offers a quick assessment of the presence of fluid. When ascitic fluid is present, one can see where it has accumulated. The other suggested probe to use during paracentesis is a 5 to 10 MHz linear probe. Its purpose is to guide needle placement. This probe is especially important if the volume of ascites is limited, thus creating a small target for fluid aspiration. All imaging is performed using the brightness or B-mode.

Anatomy and Landmarks

When scanning for fluid, the organs in the abdomen need to be clearly delineated. Organs that may contain fluid, such as the urinary bladder or obstructed bowel, will appear anechoic and may be mistaken for ascitic fluid. To delineate ascites from fluid within an organ, the clinician will need to inspect the periphery of the fluid. Fluid within the bowel or bladder is bordered by the wall of that organ, which tends to be rounded or tubular ( VIDEO 13.1). Ascitic fluid will conform to the exterior surface of organs such as mesentery and bowel, creating an irregular outline (

VIDEO 13.1). Ascitic fluid will conform to the exterior surface of organs such as mesentery and bowel, creating an irregular outline ( VIDEO 13.2). It may also be seen adjacent to the interior surface of the abdominal wall.

VIDEO 13.2). It may also be seen adjacent to the interior surface of the abdominal wall.

VIDEO 13.1). Ascitic fluid will conform to the exterior surface of organs such as mesentery and bowel, creating an irregular outline (

VIDEO 13.1). Ascitic fluid will conform to the exterior surface of organs such as mesentery and bowel, creating an irregular outline ( VIDEO 13.2). It may also be seen adjacent to the interior surface of the abdominal wall.

VIDEO 13.2). It may also be seen adjacent to the interior surface of the abdominal wall.When imaging ascites with the low frequency transducer, and especially when a large volume of ascites is present, small bowel loops are seen suspended from mesentery. Mesentery will vary in appearance from long and stalk-like to thick and sessile. If mesentery is long, the bowel will be seen floating freely and will sway in response to patient movements, to breathing, and to bowel peristalsis. When adhesions are present, the mesentery and bowel loops may be less mobile. With certain clinical conditions, loculations may form within the ascitic fluid which will limit movement of the bowel. This is clinically important since mesentery that is immobile may yield less to the advancing paracentesis needle and is thus more likely to be punctured.

Ultrasonic appearance of mesentery is relatively hyperechoic compared to the liver and spleen. Mesentery may also have a spotty hypoechoic appearance due to deposits of adipose. The ultrasonic appearance of small bowel may be either solid or tubular, depending on its contents. If the lumen content is digested matter, it appears somewhat less echoic than its mesenteric stalk. Large bowel is notable in appearance for its characteristic gas, creating a hyperechoic leading edge with deeper gray scale or “dirty” shadowing. While the small bowel will be seen throughout the abdomen, the large bowel is seen in particular locations. The ascending colon lies anterior to the right kidney in the paravertebral gutter, while the descending bowel is seen in the same location on the opposite side. The transverse colon can be identified suspended from the mesocolon in the area caudal to the stomach antrum.

Two other organs to be particularly cautious of when performing paracentesis are the liver and spleen. In patients with cirrhosis the liver will be relatively small and dense. Cirrhotic livers will appear high in the abdomen and adherent to the posterior and apical abdominal walls. If the liver is enlarged, it may extend deep into the peritoneal cavity, especially the right lobe, which may remain close to the abdominal wall. Scanning the left upper quadrant will identify splenomegaly, if present. An enlarged spleen will also extend into the peritoneal cavity, remaining close to the anterior and left lateral abdominal wall.

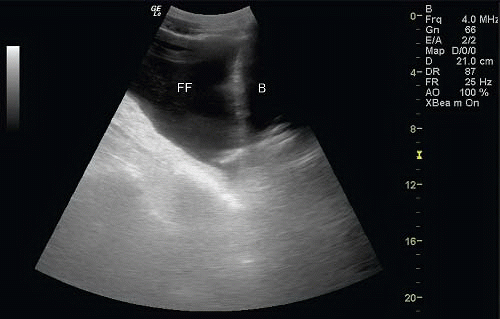

FIGURE 13.2. Rounded Wall of Urinary Bladder with Ascites in the Peritoneal Cavity. B, Bladder; FF, free fluid. |

If the paracentesis is performed with an infraumbilical approach, the urinary bladder may be seen along the anterior abdominal wall above the symphysis pubis. It is easily distinguished by its spherical shape and dense hyperechoic wall surrounding anechoic fluid (Fig. 13.2). Because the bladder is easy to discriminate, the risk of puncture is low unless it is overdistended. If the bladder is overdistended, the anterior wall may abut the lower abdominal wall and be mistaken for the peritoneal space.

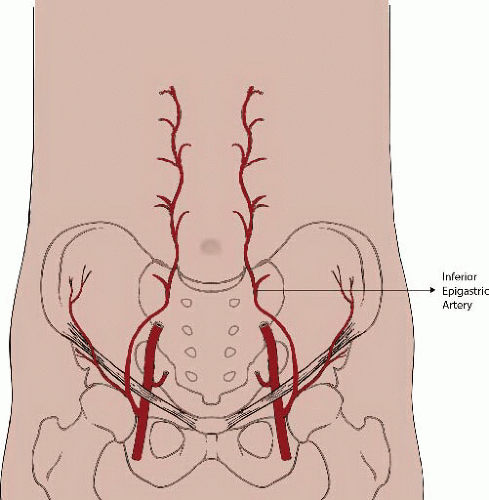

In addition to scanning the abdominal contents, the abdominal wall must be closely inspected and scanned for abnormalities. Certain conditions will preclude an area from paracentesis, including abdominal wall abscess or cellulitis, any hernias, or an area of collected superficial veins. One also needs to be aware of, and to avoid, the inferior epigastric artery. This artery runs from the femoral outlet to the distal one-third of the rectus abdominus muscle. At this point the artery runs cephalad, usually along the posterior aspect of the muscle to join with the superior epigastric artery. In the abdominus rectus, the artery is 4 to 8 cm off the midline (Fig. 13.3).

Procedure

In preparation for scanning, the patient should be in a comfortable supine, semi-reclined position. This position will allow the ascites to accumulate in the lower abdomen. When deciding where to perform the paracentesis, the right or left lower quadrants are generally favored over the more traditional infraumbilical approach. One study compared the left lower quadrant to the infraumbilical area and found the depth of the fluid was generally greater in the lateral abdomen (6). In any given patient, however, the most accumulated fluid may be in any of these three areas, and ultrasound provides the advantage of locating the largest and most accessible fluid.

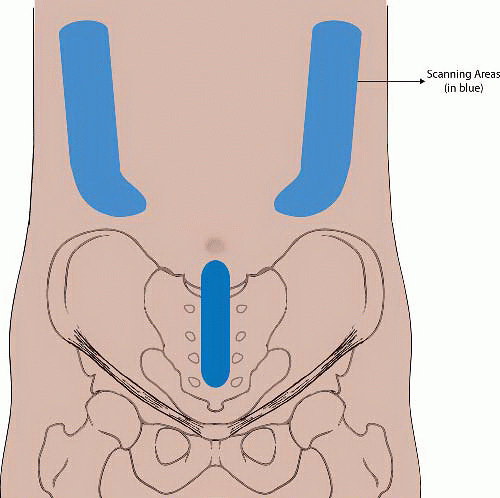

Scanning for a paracentesis site needs to be systematic, beginning in one location and progressing through the others (Fig. 13.4). With the lateral quadrants, place the low frequency transducer just above the anterior superior iliac crest, and work in a cephalad direction along the pericolic gutter. As the transducer is moved up the abdomen, fan the probe in a medial direction toward the midline and in

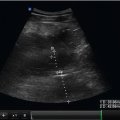

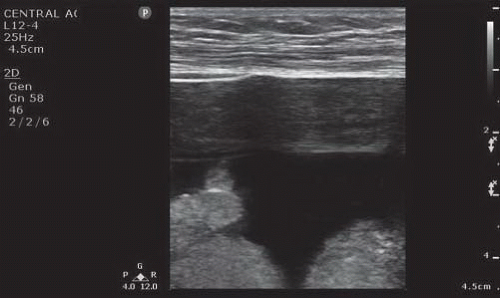

a lateral direction toward the edge of the peritoneum. The transducer may need to be shifted in a medial or lateral direction, depending on the size of the patient’s abdomen. When a potential site for paracentesis is identified, rotate the probe 90 degrees to ensure that the fluid is present in two planes. When scanning the infraumbilical area, place the probe a couple of centimeters below the umbilicus in the midline, and move in a caudal direction. Again, check each area of fluid in two perpendicular planes. The minimal depth of fluid needed to safely attempt paracentesis is generally considered about 3 cm (Fig. 13.5). For those experienced with the use of ultrasound guidance, a depth of 2 cm may be acceptable. The decision to proceed with paracentesis is determined by the clinical situation.

a lateral direction toward the edge of the peritoneum. The transducer may need to be shifted in a medial or lateral direction, depending on the size of the patient’s abdomen. When a potential site for paracentesis is identified, rotate the probe 90 degrees to ensure that the fluid is present in two planes. When scanning the infraumbilical area, place the probe a couple of centimeters below the umbilicus in the midline, and move in a caudal direction. Again, check each area of fluid in two perpendicular planes. The minimal depth of fluid needed to safely attempt paracentesis is generally considered about 3 cm (Fig. 13.5). For those experienced with the use of ultrasound guidance, a depth of 2 cm may be acceptable. The decision to proceed with paracentesis is determined by the clinical situation.

FIGURE 13.5. Image of an Adequate Depth of Ascites Needed to Perform Ultrasound-Guided Paracentesis. The image includes mesentery and bowel deep to the fluid. |

After an insertion site is chosen and the skin is prepared for asepsis, the clinician can choose between a static and a dynamic technique. If the fluid collection is large, a static approach is satisfactory, as long as the patient remains in the same position. In general, a dynamic technique is safer and recommended. If a dynamic technique is chosen, the linear probe is covered with a sterile sleeve and placed on the sterile field or on a sterile procedure tray. The two techniques used for any needle guidance procedure using ultrasound are the in-plane or long axis approach and the out-of-plane or short axis approach. Whichever the clinician is more comfortable with is acceptable. The short axis approach is easier, although it carries a risk of inserting the needle too deep, since only the section of the needle directly under the transducer is seen. When there is an abundance of fluid, this method should not be a problem. When there is little fluid to access, particularly when sensitive structures are nearby, the long axis approach is preferred. This approach, though more difficult, provides real-time visualization of the entire length of the needle as it enters the peritoneum. Either technique can be performed by one clinician using the sterile transducer; the needle is inserted with the dominant hand while the other hand holds the transducer.

Whichever approach is used, one must be sure to reexamine the chosen site in two perpendicular planes to assure an adequate volume of fluid. Bowel will tend to move over time due to peristalsis. It also moves when the patient adjusts his/her upper body position or coughs. If the fluid is no longer present at the premarked site, scan the adjacent sterilized area, and if need be, repeat the entire search and aseptic preparation. After the proposed site and path of the needle catheter is determined, local anesthesia should be injected down to and including the parietal peritoneum. Using the short axis approach the needle catheter is inserted next to the middle of the long edge of the linear probe as the probe is held perpendicular to the skin. The transducer should be moved forward as the needle advances, ideally scanning the tip of the needle. If need be, the clinician can halt the needle and shift the transducer away from and then back toward the needle to clarify where the tip of the needle is located. When the needle is about to enter the peritoneum,

the inner wall of the abdomen will be seen tenting inward. At this point, short controlled jabs with the needle may help to pierce the peritoneal fascia. Once in the peritoneal cavity, the needle is seen as a hyperechoic point within the anechoic fluid. If the long axis approach is used, the entire needle is followed as it tracks through the abdominal wall and into the peritoneum ( VIDEO 13.3). With either approach, make sure that the needle has advanced about a centimeter into the ascites before collecting fluid and advancing the catheter. At this stage the ultrasound transducer can be set aside and the procedure can be completed in the usual manner.

VIDEO 13.3). With either approach, make sure that the needle has advanced about a centimeter into the ascites before collecting fluid and advancing the catheter. At this stage the ultrasound transducer can be set aside and the procedure can be completed in the usual manner.

the inner wall of the abdomen will be seen tenting inward. At this point, short controlled jabs with the needle may help to pierce the peritoneal fascia. Once in the peritoneal cavity, the needle is seen as a hyperechoic point within the anechoic fluid. If the long axis approach is used, the entire needle is followed as it tracks through the abdominal wall and into the peritoneum (

VIDEO 13.3). With either approach, make sure that the needle has advanced about a centimeter into the ascites before collecting fluid and advancing the catheter. At this stage the ultrasound transducer can be set aside and the procedure can be completed in the usual manner.

VIDEO 13.3). With either approach, make sure that the needle has advanced about a centimeter into the ascites before collecting fluid and advancing the catheter. At this stage the ultrasound transducer can be set aside and the procedure can be completed in the usual manner.Pitfalls and Complications

When performing any procedure using needle placement, the inherent risk is penetrating a sensitive structure. This risk is reduced with ultrasound guidance, and is related to the experience one has with both ultrasound and paracentesis. The most common complication of ultrasound-guided paracentesis is bleeding. Bleeding can occur from penetrating a solid organ or from penetrating an abdominal wall vessel. The organs most at risk of penetration are an enlarged liver or spleen. Bowel is less at risk of penetration, presumably because it is suspended from mesentery and freely floating in ascites ( VIDEO 13.4). Even if bowel is penetrated, the risk of peritonitis is generally believed to be low. Bleeding complications have been observed in <1% of patients using ultrasound guidance (7). Rates of peritonitis or infection within the abdominal wall ranged from 0.06% to 0.16% in two studies using ultrasound guidance (2,7).

VIDEO 13.4). Even if bowel is penetrated, the risk of peritonitis is generally believed to be low. Bleeding complications have been observed in <1% of patients using ultrasound guidance (7). Rates of peritonitis or infection within the abdominal wall ranged from 0.06% to 0.16% in two studies using ultrasound guidance (2,7).

VIDEO 13.4). Even if bowel is penetrated, the risk of peritonitis is generally believed to be low. Bleeding complications have been observed in <1% of patients using ultrasound guidance (7). Rates of peritonitis or infection within the abdominal wall ranged from 0.06% to 0.16% in two studies using ultrasound guidance (2,7).

VIDEO 13.4). Even if bowel is penetrated, the risk of peritonitis is generally believed to be low. Bleeding complications have been observed in <1% of patients using ultrasound guidance (7). Rates of peritonitis or infection within the abdominal wall ranged from 0.06% to 0.16% in two studies using ultrasound guidance (2,7).HERNIA REDUCTION

Clinical Indications

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree