Pediatric Procedures

Amanda Greene Toney

Russ Horowitz

INTRODUCTION

While there are many similarities in indications, techniques, and complications in ultrasound-guided procedures done in adults and children, there are also important differences. Some of these are simple yet subtle modifications in technique. In some cases (e.g., suprapubic bladder aspiration), the technique is rarely performed in adults. The following chapter reviews differences between ultrasound-guided procedures in children and adults, focusing on salient features that should be noted to optimize technique.

CENTRAL VENOUS ACCESS

Central venous access in children can be particularly challenging. Difficulties in the pediatric population include smaller vein diameter, variation in vessel anatomy with age (1,2), uncooperative patients, and tissue laxity and compressibility (3). Adverse event rates for central venous access tend to be higher in children and include thrombosis, arterial/cardiac perforation, cardiac arrhythmias, air embolism, catheter fragment embolism, infection, pneumothorax, hemothorax, and nerve injury (3, 4, 5). Ultrasound assistance for central venous catheter placement has been found to increase success rate, decrease number of attempts, and decrease complication rates in children (6,7). When compared to the external landmark-based approach, ultrasound-guided cannulation results in a reduced number of arterial punctures and a number of sites attempted. These advantages have been shown even in very young children and in medical, surgical, and trauma settings (1,8, 9, 10, 11). Both internal jugular and femoral sites benefit from ultrasound guidance (12). Consensus data favor the use of ultrasound-guided central venous access in children, and some pediatric emergency departments (EDs) now mandate its use.

Clinical Indications

Indications for central venous access in children are similar to those for adults, including:

Fluid resuscitation and delivery of medications, especially for hypertonic fluids and vasopressors.

Central venous pressure monitoring.

Venous access for patients with difficult peripheral access.

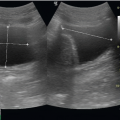

Image Acquisition

As in adults, a high-frequency (7.5 to 10 MHz) probe should be selected and the appropriate vein, adjacent artery, and surrounding structures identified. Color flow and Doppler may be useful to confirm the anatomy. Given the superficial nature and pliability of pediatric vasculature, care must be taken to prevent compression of venous and arterial structures. Light contact should be maintained between both the transducer and the overlying skin. The weight of the transducer alone is enough to produce complete collapse of the vessel and interfere with visualization. Take care not to rest

the gripping hand on the skin surface, as this will compress the target and neighboring vessels.

the gripping hand on the skin surface, as this will compress the target and neighboring vessels.

Anatomy and Landmarks

Ultrasound offers a valuable adjunct to central line placement. However, clinicians still need to be familiar with the anatomy of the vasculature and surrounding structures. The technological advantage of ultrasound does not replace the need for a solid understanding of the traditional landmarks described below.

Femoral vein approach

The femoral vein is the preferred site for central access in pediatric resuscitation and in children with difficult access. During resuscitation with ongoing CPR and airway management, it is often difficult to access the head, neck, and chest for central line placement. The femoral vein landmarks are readily identified and hemostasis easily achieved when pressure is applied. There is a lower complication rate with femoral vein line placement when compared with internal jugular and subclavian lines (3,13, 14, 15). Once thought to be at higher risk for central line infection, the infection risk with femoral central lines is similar to that of internal jugular and subclavian vein central lines (16, 17, 18, 19, 20).

With the patient lying in the supine position and the hip abducted and externally rotated, the femoral vein lies 1 to 2 cm inferior to the inguinal ligament about halfway between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic symphysis (3). The femoral vein is located just medial to the femoral artery pulsation. A towel roll beneath the ipsilateral gluteal region may assist in landmark identification. Of note, Warkentine et al. reported that the location of the femoral vein relative to the femoral artery varies in children (2). In 12% of patients, the femoral vein was completely or partially overlapped by the femoral artery, giving further support for ultrasound-guided cannulation.

Internal jugular vein approach

The internal jugular vein is often the second choice in central venous access in children. The internal jugular vein is accessed by first placing the child in a supine 10 to 20 degrees Trendelenberg position to aid in venous distension (3). A towel roll may be placed between the child’s scapulae to assist in landmark recognition. Right-sided access is most commonly attempted given the lack of acute angles with the right internal jugular vein, and a preference to avoid the left sided thoracic duct and high riding pleural dome on the left. The internal jugular vein lies between the two heads of the sternocleidomastoid muscle; the carotid artery is located deep and medial to the vein.

Subclavian vein approach

The subclavian vein is the least common site for central venous access in children in an acute medical situation due to difficulty in accessing the location, the higher associated complication rate, and the significant degree of skill necessary to place the catheter (3,21). In children <1 year old, the subclavian vein arches more superiorly as it travels toward the atrium, creating sharp angles, and the vessel diameter is smaller than that of the internal jugular vein, making cannulation especially difficult. Landmarks are less identifiable given the small size and plasticity of the pediatric chest. The right side of the chest is preferred for reasons mentioned previously. The infraclavicular approach is usually preferred due to a lower complication rate.

The child is placed in a supine 10 to 20 degree Trendelenberg position with the head turned to the contralateral side similar to the internal jugular vein procedure (3). A towel roll may be placed between the scapulae to allow the shoulders to be in a dependent position from the mid-line of the chest. The ipsilateral arm is placed at the patient’s side.

Procedure

Although the anatomic landmarks and techniques are very similar in children and adults, additional special considerations must be made for children undergoing central venous catheter placement. These include patient preparation, analgesia, sedation, and equipment selection. Local anesthetics are necessary to reduce the pain of the initial needle insertion. Options include local injections or needleless transdermally delivered analgesia. In addition to a local anesthetic, anxiolysis and/or sedation are often necessary for uncooperative children. Midazolam is an excellent choice as an anxiolytic as it can be given via the intranasal (0.2 to 0.3 mg/kg), oral (0.25 to 0.5 mg/kg), or intravenous (0.05 to 0.1 mg/kg) route. Numerous medication combinations are available for children undergoing sedation. The choice of particular agent(s) should be based on the clinical scenario and patient status. Customary choices include a narcotic/benzodiazepine combination (e.g., fentanyl and midazolam) and ketamine. Both options provide sufficient analgesia, sedation, and amnesia. Age- and size-appropriate equipment is essential. Continuous cardiorespiratory monitoring must be in place. Although airway support is generally not required with these agents, pediatric specific supplies and physicians skilled in pediatric intubation must be present.

The technique for venipuncture is similar for adults and children, and is the same regardless of anatomical approach. A variety of techniques, including dynamic and static techniques, in-plane and out-of-plane approaches, and one-operator versus two-operator procedures are described in detail in Chapter 8. However, the angle of needle entry varies for different sites. For the femoral vein approach, the vessel is much more superficial in children, and therefore the needle should be inserted at a more shallow angle. This allows for better needle visualization. Pediatric vascular walls are very pliable, so a delicate approach with a sharp poke through the near field border of the vessel is needed. The internal jugular vein in children is superficial, and the needle needs to be inserted only 0.5 to 3.0 cm for venous access. Minimal pressure is applied with the ultrasound probe in the region to avoid fully compressing the vein. When using the infraclavicular approach for subclavian vein cannulation, the needle entry point is at or just lateral to the midclavicular line below the clavicle. The needle is inserted 2 to 4 cm below the surface of the clavicle in the direction of the sternal notch in parallel with the horizontal plane of the chest. Small inferior adjustments can be made in children if the first attempt is unsuccessful, but subclavian artery puncture and pneumothorax are potential complications to consider.

Pitfalls and Complications

A variety of technical factors can affect the ease and success of ultrasound-assisted venous access, including:

PERIPHERAL VENOUS ACCESS: COMPARISON BETWEEN CHILDREN AND ADULTS

Pediatric studies support the use of ultrasound guidance for peripheral venous access. Doniger et al. found a shorter time to cannulation, fewer attempts, and a greater success rate with ultrasound-guided peripheral access compared to the traditional technique in the pediatric emergency department in young children (22). Specific recommendations in smaller children include using a 22-gauge catheter that is longer and wider, allowing for good visibility of the needle on ultrasound and for cannulation of a slighter deeper vein (23). By nature, pediatric vessels are short. Prior to insertion, the length of the vein should be scanned to ensure that the site of insertion provides a long enough path to pass the catheter.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree