Bedside Sonography of the Bowel

Timothy Jang

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, sonography has given way to computerized tomography (CT) as the primary imaging modality for bowel. However, CT may not always be available in a timely fashion, exposes patients to contrast, involves radiation, requires technician time, and may be associated with a delay in diagnosis. Although the presence of air in the bowel may limit sonographic visualization, sonography can decrease the time to diagnosis without requiring contrast administration, radiation exposure, or technician time for the diagnosis of important abdominal conditions such as bowel obstruction, inflammatory disorders of the bowel (including appendicitis, diverticulitis, and inflammatory bowel disease), and the presence of hernias or abdominal wall masses.

BOWEL OBSTRUCTION

Introduction

Small bowel obstructions (SBOs) represent 20% of surgical admissions for acute abdominal pain (1), but are difficult to diagnose since they can mimic other causes of abdominal pain (2). Classically, diagnosis has been made by history and physical exam with confirmation by plain film radiography, which is frequently nondiagnostic (1,2) and insensitive (2,3). CT is an accurate diagnostic modality that is often used to assess for SBO, but bowel sonography can be done quickly to assess patients for possible SBO at decreased cost without radiation exposure and can be repeated easily to assess resolution of symptoms.

Clinical Applications

Bedside sonography is useful to:

Evaluate patients with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and/or abdominal distension

Screen for bowel obstructions

Identify characteristics of ischemia suspicious for a strangulated obstruction

Locate site (transition point) and potential source of obstruction

Identify abnormal bowel thickness seen in a variety of conditions (inflammatory, infectious, neoplastic, and ischemic)

Image Acquisition

The highest frequency probe possible is selected based on the patient’s habitus (typically 7.5 MHz in small, thin children vs. 3.0 to 5.0 MHz in larger adults). Even in adults, once an abnormality is identified, switching to a higher frequency transducer may provide improved resolution and visualization of an identified area of pathology.

Two main approaches can be used to evaluate the bowel. The first is to place the probe over the site of maximal tenderness and then scan the area in the transverse and longitudinal planes. This often reduces the time of the examination, but may miss pathology due to referred pain. The second technique is called lawnmowering, where the probe is placed in the right lower quadrant in the transverse plane, then moved up and down the abdominal wall until the entire abdomen is imaged ending in the left lower quadrant (Figs. 12.1 and 12.2). This method is then repeated starting in the left lower quadrant in the longitudinal plane with the probe moved side to side until the entire abdomen is imaged (Figs. 12.3 and 12.4). This approach takes more time than a simple, localized exam, but may detect referred causes of pain.

The scan can be optimized using the technique of graded compression, by gently and gradually applying pressure to the anterior abdominal wall. Graded compression will displace, and then compress, normal bowel, thus helping to identify abnormal, pathologic bowel.

Normal Ultrasound Anatomy

The abdominal wall is comprised of skin, subcutaneous adipose, muscle and its surrounding fascia, and finally bowel. The normal bowel wall is comprised of an innermost echogenic superficial mucosa, surrounded by five alternating hypoechoic and echogenic layers that represent the muscularis mucosa, muscularis propia, serosa, and their interfaces (4). However, most of the time, especially in adults, these layers appear as a nearly singular echogenic layer, and operators should not spend a tremendous amount of time differentiating these layers. The sonographer should carefully assess the following:

Bowel contents (aerated or fluid-filled)

Appearance and thickness of the bowel wall (normal is regular and <4 mm thick) (4)

Peristalsis (normal bowel has visible movement, a to-and-fro of bowel contents)

Compressibility (normal bowel compresses with gentle pressure)

FIGURE 12.1. Placement of Probe in Right Lower Quadrant to Begin Lawnmowering Sweep of Abdomen Using Transverse Probe Orientation. |

Pathology

Small bowel obstruction

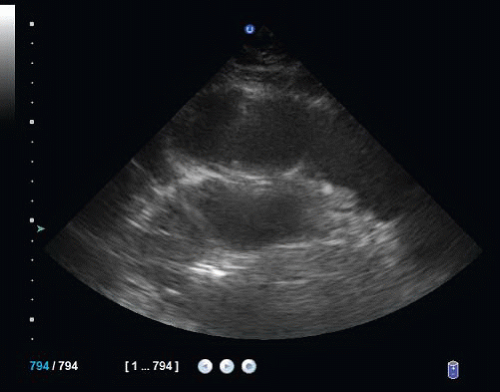

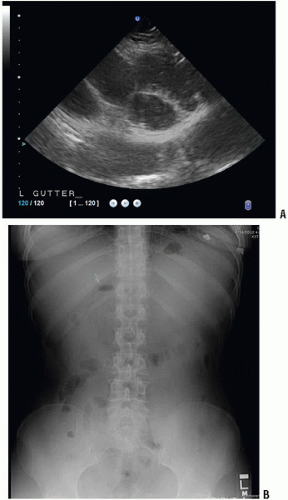

The diagnosis of an SBO is made by detecting dilated, noncompressible small bowel proximal to collapsed, compressible small bowel (Figs. 12.5, 12.6, 12.7 and 12.8;  VIDEO 12.1). When the bowel is dilated, it suggests either the presence

VIDEO 12.1). When the bowel is dilated, it suggests either the presence

of an ileus or obstruction (Fig. 12.9). Lack of compressibility makes an obstruction more likely than an ileus, but does not definitively differentiate between an ileus and an obstruction, while lack of peristalsis can be associated with either etiology. If abnormal bowel is encountered, its course should be followed until normal bowel is visualized. This allows for identification of a transition point and other obstructive causes such as intussusception or compressing masses.

VIDEO 12.1). When the bowel is dilated, it suggests either the presence

VIDEO 12.1). When the bowel is dilated, it suggests either the presence of an ileus or obstruction (Fig. 12.9). Lack of compressibility makes an obstruction more likely than an ileus, but does not definitively differentiate between an ileus and an obstruction, while lack of peristalsis can be associated with either etiology. If abnormal bowel is encountered, its course should be followed until normal bowel is visualized. This allows for identification of a transition point and other obstructive causes such as intussusception or compressing masses.

Large bowel versus small bowel

Although large bowel obstruction (LBO) is much less common than SBO, approximately 15% of patients with LBO may appear initially to have an SBO (7). LBO can be differentiated from SBO sonographically by the accumulation of gas in the colon, resulting in the appearance of peripherally located (vs. centrally located small bowel), dilated bowel filled with dense spot echoes that represent feculent, fluid contents, including small bubbles of gas. A large bowel diameter >5 cm is abnormal, suggesting an obstruction or toxic megacolon.

Bowel dilation

The differential diagnosis for bowel dilation includes partial and complete SBO, partial and complete LBO, ileus, sprue, colitis, and toxic megacolon.

Bowel strangulation

Sonographic findings that suggest bowel strangulation include (1) dilated, noncompressible, non-peristalsing or akinetic bowel, (2) rapid accumulation of localized free fluid around abnormal bowel, and (3) asymmetric bowel wall edema with abnormal diameter and/or nonperistalsis. Lack of compressibility suggests a complete obstruction with increased intraluminal pressure, raising concern for strangulation.

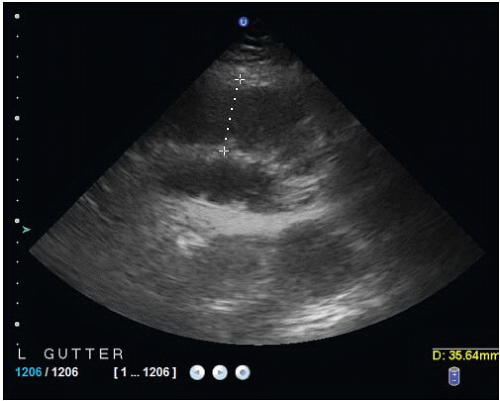

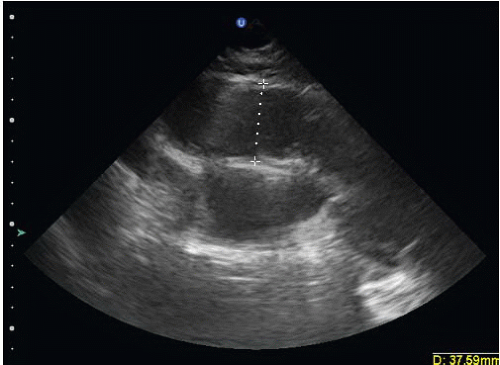

FIGURE 12.5. A: Dilated, fluid-filled bowel in the left pericolic gutter. B: Corresponding abdominal x-ray. |

FIGURE 12.7. Measurement of Bowel Luminal Diameter in the Left Pericolic Gutter Demonstrating Dilated Bowel. |

FIGURE 12.8. Measurement of Bowel Luminal Diameter in the Supra-umbilical Region Demonstrating Dilated Bowel. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree