(1)

Department of Radiology, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

(2)

Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Case 2.1: Solitary Pulmonary Nodule

History

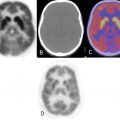

A 50-year-old male, incidentally diagnosed with a lung nodule in the right lung apex on X-ray and confirmed on CT. Patient was referred for PET/CT evaluation of solitary pulmonary nodule.

Hypermetabolic right upper lobe pulmonary nodule with pleural tag (yellow arrow), measures 1.9 × 0.9 cm, anterolaterally, SUVmax 2.9, worrisome for neoplastic process. Remainder of the study was unremarkable.

Impression

Hypermetabolic solitary pulmonary nodule, worrisome for primary neoplasm. (Patient underwent Rt. Upper lobe wedge resection. Pathology: granulomatous caseating inflammation.)

Pearls and Pitfalls

A major application of PET is in the workup of indeterminate solitary pulmonary nodules, defined as noncalcified nodules, 3 cm or smaller, in the lung parenchyma that are found on chest radiography or CT (both of which play vital role in the diagnosis and management of many pulmonary disorders) [1]. However, FDG-PET studies can be falsely positive, primarily due to inflammatory and granulomatous changes, as might be seen in tuberculosis, fungal infections, and sarcoidosis [1].

Discussion

Solitary pulmonary nodule (SPN) is defined as a single spherical lesion within the lung parenchyma without associated atelectasis or adenopathy. Current convention is that SPNs are 3 cm or less in diameter. Larger lesions should be referred to as pulmonary masses and should be managed with the understanding that they are most likely malignant; prompt diagnosis and resection are usually advisable [2].

SPNs are caused by a variety of benign and malignant processes. Solitary pulmonary nodules are commonly encountered in clinical practice—about 150,000 new ones are discovered each year in the United States, of which 30–50 % are malignant [1]. Of the benign lesions, 80 % are caused by infectious granulomas, 10 % are caused by hamartomas, and the remaining 10 % are caused by a variety of rarer disorders including noninfectious granulomas and other benign tumors [2].

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy is recommended as the first-line diagnostic approach in the workup of SPN.

PET should be reserved for those situations in which a biopsy is inconclusive or contraindicated [3].

Initial studies indicated that a standardized uptake value of 2.5 might distinguish benign from malignant processes; however, later studies have shown that there can be some overlap in these values between benign and malignant processes [1].

Case 2.2: Non-small Cell Lung Cancer

History

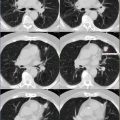

A 60-year-old female with history of adenocarcinoma involving the right lung. Additional history of left breast cancer in the past.

Pretherapy images demonstrate hypermetabolic pulmonary nodule measuring 2.4 × 1.6 cm in the right lung base, SUVmax 3.2.

Impression

Hypermetabolic solitary pulmonary nodule in the right lung base, consistent with malignancy (on biopsy). (The patient later underwent surgical resection of the right lower lobe with nodal dissection.)

Posttreatment/follow-up PET/CT demonstrates findings consistent with status post resection of previously noted hypermetabolic pulmonary nodule (seen in Fig. 2.1) at the right lung base. Mild hypermetabolic activity at the lower right costovertebral junction represents inflammation from recent resection. Linear, left chest wall uptake is related to prior breast cancer therapy.

Impression

Post-therapy scan, compatible with treated disease with no scan evidence of local recurrence or distant metastasis.

Pearls and Pitfalls

Most solitary pulmonary nodules without increased FDG uptake are highly unlikely to be malignant. However, FDG-PET scans are occasionally falsely negative in cases of well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, bronchoalveolar cell carcinoma, and carcinoid. The spatial resolution of most commercial PET scanners is about 5–6 mm; FDG-PET is less accurate for pulmonary nodules smaller than 1 cm [1].

Discussion

Case 2.3: Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Lung

History

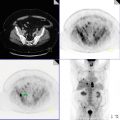

A 67-year-old female with right lung, pleural-based squamous cell carcinoma (biopsy proven).

Large 6.4 cm hypermetabolic, pleural-based mass in the right middle lobe (RML), SUVmax 8.2, with area of central necrosis (yellow arrow) within it. Hypermetabolic focus in the (contralateral) left axillary region (red arrow) corresponds to lymph node on CT.

Impression

Stage III lung cancer. Hypermetabolic pleural-based RML lung malignancy (proven on biopsy as squamous cell carcinoma) with contralateral left axillary lymph node metastasis.

Pearls and Pitfalls

With regard to PET/CT imaging, patient motion (e.g., respiratory motion) can produce significant artifacts on fused images and may cause confusion as to the correct position of the origin of the detected photon [5]. It is recommended to review CT and PET images separately for comparison.

Discussion

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines were reviewed on March 13, 2012 for utilization of F18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET and PET/CT.

Practice guidelines from the SNM, NCCN, and other professional groups summarized for lung cancer [6]:

1.Characterization of an indeterminate pulmonary nodule which is at least 8–10 mm in diameter

2.Initial staging in patients with non-small cell lung cancer and selected patients with small cell lung cancer

3.Delineation of gross tumor volume in patients receiving radiation therapy

PET and PET/CT are approved by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) for:

a.Characterization of solitary pulmonary nodules.

b.Development of initial treatment strategy and subsequent treatment strategy in patients with NSCLC.

c.Development of initial treatment strategy in patients with SCLC. The use of PET/CT for subsequent treatment strategy falls under “CED” (coverage with evidence of development) category.

Case 2.4: Stage IIIB Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC)

History

A 75-year-old male with right middle lobe non-small cell lung cancer, clinical T4b N2 M0, stage IIIB.

Large, irregular, hypermetabolic mass (>7 cm), SUVmax 13.6, in the medial segment of the right middle lobe, with central necrosis (appearing photopenic on PET). There is invasion of the tumor into the right minor fissure and extends superiorly into the right upper lobe. A satellite hypermetabolic nodule, SUVmax 6.6, seen posterior to the dominant mass (yellow arrow).

Impression

Non-small cell lung carcinoma (biopsy proven), in the RML, stage IIIB.

Pearls and Pitfalls

PET is a useful tool for identifying patients at high risk for disease recurrence and restaging following neoadjuvant chemotherapy with or without radiation. PET is particularly useful when posttreatment scarring and pleural thickening limit the role of CT for disease assessment [7].

Discussion

Malignant lung neoplasms arise from respiratory epithelium (bronchi, bronchioles, and alveoli).

Four major cell types make up 90 % of all primary lung neoplasms:

1.Squamous cell or epidermoid carcinoma

2.Small cell (also called oat cell) carcinoma

3.Adenocarcinoma (including bronchoalveolar)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree