There are 2 types of central nervous system lymphoma: primary and secondary. Both have variable imaging features making them diagnostic challenges. Furthermore, a patient’s immune status significantly alters the imaging findings. Familiarity with typical appearances, variations, and common mimics aids radiologists in appropriately considering lymphoma in the differential diagnosis. Moreover, special types of lymphoma, such as lymphomatosis cerebri, intravascular lymphoma, and lymphomatoid granulomatosis, also are found. This article discusses uncommon types of lymphoma and the differential diagnosis for focal, multifocal, meningeal, and infiltrative lymphomas.

Key points

- •

Lymphomatosis cerebri (LC) is a rare type of infiltrative lymphoma that usually does not enhance.

- •

In LC, restricted diffusion is minimal or absent.

- •

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) may distinguish LC from gliomatosis cerebri (GC).

- •

Intravascular lymphoma (IVL) may mimic ischemic lesions.

Special lymphoma types

Lymphomatosis Cerebri

LC is a rare variant of primary central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma (PCNSL) pathologically characterized by diffuse cerebral infiltration of a noncohesive mass of malignant lymphoid cells. The clinical picture is variable and includes abnormal behavior, personality changes, gait disturbance, seizures, memory deficits, and rapidly progressive dementia and weight loss.

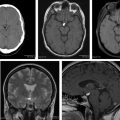

White matter abnormalities in LC affect all of the brain. MR imaging findings are extensive, diffuse T2 and FLAIR-weighted hyperintense lesions without formation of a cohesive mass and no contrast enhancement in both cerebral hemispheres and brainstem ( Fig. 1 ). Subtle or patchy enhancement may be seen. There may be a transition from nonenhancing to enhancing lesions suggesting that progression and evolution is associated with disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Restricted diffusion may be minimal or absent (see Figs. 1 F, G). Many cases respond to steroids alone, at least initially. To achieve complete remission, steroids are usually followed by radiotherapy, cisplatin, or methotrexate.

Pearls

- •

LC is a diagnostic challenge.

- •

In patients presenting with diffuse, bilateral, asymmetric signal abnormalities in white matter, infiltrative lymphoma should be considered, especially if there is callosal involvement.

- •

Consider brain biopsy in rapidly progressive cognitive decline to allow earlier therapy for a potentially curable disease.

- •

Awareness of this rare disease and early biopsy are required for preventing a poor clinical outcome.

Intravascular Lymphoma

IVL was originally described in 1959 and designated as “angioendotheliomatosis proliferans systemisata.” Since then, it has been referred to as neoplastic angioendotheliosis, malignant angioendotheliomatosis, and angiotropic large-cell lymphoma.

IVL is a rare subtype of extranodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with a distinct presentation. Anatomically, it is characterized by proliferation of clonal lymphocytes within small vessels with relative sparing of surrounding tissues. The degree of sparing of surrounding tissues and absence of lymphoma cells in lymph nodes and reticuloendothelial system is a hallmark of the disease.

Epidemiology and risk factors

IVL is a rare disease with an incidence of less than 1 person per million. It has been described in patients ranging from 34 to 90 years of age with a median age of 70 years and occurs equally in women and men. There are no known risk factors for IVL.

Clinical features

IVL is heterogeneous in its clinical presentation and affects the small vessels in nearly every organ. Although IVL is a clonal proliferation of lymphocytes, it is uncommon to find significant adenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, or malignant cells in the peripheral blood. Absence of IVL in the traditional sites of presentation of lymphoma makes accurate and timely diagnosis difficult. Clinical symptoms depend on specific organ involvement, which most often includes the CNS and skin. Patients with CNS compromise present with focal sensory or motor deficits, generalized weakness, altered sensorium, rapidly progressive dementia, seizures, hemiparesis, dysarthria, ataxia, vertigo, and transient visual loss. Initial diagnoses of stroke, encephalomyelitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, vasculitis, and multiple sclerosis (MS) are often made and a diagnosis of IVL is often not established until autopsy.

Laboratory findings

Anemia, elevated lactate dehydrogenase, and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate are common laboratory abnormalities in IVL. A majority of studies have shown IVL absent in peripheral blood smears.

Imaging findings

The diffuse nature of brain involvement, with multifocal abnormalities, is reflected by its MR imaging appearance. MR imaging findings of IVL include the following.

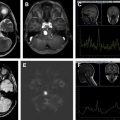

Infarct-like lesions

Multiple, round or oval metachronous cortical or subcortical lesions that are hyperintense on T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images, some presenting with restricted diffusion suggestive of small vessel ischemia or demyelination ( Figs. 2 and 3 ). Although classically IVL is thought to remain strictly confined to vascular lumina in the CNS, parenchymal and callosal involvement may represent extravascular spread of tumor and may help suggest the diagnosis (see Figs. 2 and 3 ).

Infarct-like lesions correlate with commonly reported findings of multiple recent or resolving infarctions. The lesions may not enhance (see Fig. 3 D). Infarct-like lesions suggest that the tumor predominantly involves small arteries. This pattern was reported in 36% of patients with IVL who had brain MR imaging.

Nonspecific white matter lesions

Poorly defined nonspecific white matter lesions have been reported, especially in the periventricular areas, mimicking leukoaraiosis ( Fig. 4 ). Some investigators speculate that severe vascular infiltration by tumor cells leads to small vessel occlusion, ischemia, and infarction, which are responsible for these imaging findings.

Masslike lesions

Williams and colleagues noticed that intraparenchymal mass lesions have extensive vasogenic edema and mass effect contrary to the characteristic features of tumor cell infiltration predominantly in the vascular lumen. Nodular-enhancing lesions may disappear in follow-up MR imaging studies and be replaced by other enhancing lesions in other locations reflecting a dynamic behavior of IVL (see Fig. 4 J–O).

Meningeal enhancement

Meningeal enhancement is sometimes present in patients with IVL, although the nature of this finding is unclear. Severe meningeal inflammatory reaction with tumor cells has been demonstrated in post mortem examinations.

Hyperintense T2 lesions in the pons

T2 hyperintense lesions in the central pons without contrast enhancement or diffusion restriction have been reported. These lesions in the central pons exclude the pontine tegmentum and ventrolateral region and are similar to those of pontine osmolytic demyelination and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome or those from intracranial dural arteriovenous fistula with venous congestion.

Occlusion of capillaries causes diffuse white matter abnormal intensities. Some investigators speculate that the hyperintense pons lesions result from occlusion of capillaries.

A majority of cases of IVL present as CNS abnormalities, particularly with diffuse encephalopathy, and/or subacute progressive multifocal neurologic deficits and MR imaging findings that resemble vasculitis.

Lymphomatoid Granulomatosis

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis (LG) is a rare angiocentric, destructive lymphoproliferative disorder. It mainly involves the lungs followed by the skin and brain. Isolated CNS involvement is rare. When it affects the CNS, it is more commonly due to spread of systemic LG to the CNS. Although it may develop in the immunocompetent, LG is more common in the immune suppressed, including AIDS patients.

Clinical picture

Clinical features of CNS involvement are highly variable, including headache, seizure, blindness, cranial nerve palsies, hemiparesis, ataxia, spastic gait, dementia, and altered consciousness.

Imaging findings

LG presents diverse neuroimaging features, such as multiple punctuate or linear enhancement, ringlike enhancement, large mass lesions, and leptomeningeal and choroid plexus involvement. Multifocal T2 hyperintensities with linear or punctuate contrast enhancement are common ( Fig. 5 ) and thought to be due to the angiocentric and angiodestructive nature of the disease. The lesions typically involve the white matter and deep gray nuclei. Leptomeningeal and cranial nerve enhancement are also common.

MR imaging is more sensitive than cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis or flow cytometry for detecting CNS involvement from LG.

Special lymphoma types

Lymphomatosis Cerebri

LC is a rare variant of primary central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma (PCNSL) pathologically characterized by diffuse cerebral infiltration of a noncohesive mass of malignant lymphoid cells. The clinical picture is variable and includes abnormal behavior, personality changes, gait disturbance, seizures, memory deficits, and rapidly progressive dementia and weight loss.

White matter abnormalities in LC affect all of the brain. MR imaging findings are extensive, diffuse T2 and FLAIR-weighted hyperintense lesions without formation of a cohesive mass and no contrast enhancement in both cerebral hemispheres and brainstem ( Fig. 1 ). Subtle or patchy enhancement may be seen. There may be a transition from nonenhancing to enhancing lesions suggesting that progression and evolution is associated with disruption of the blood-brain barrier. Restricted diffusion may be minimal or absent (see Figs. 1 F, G). Many cases respond to steroids alone, at least initially. To achieve complete remission, steroids are usually followed by radiotherapy, cisplatin, or methotrexate.

Pearls

- •

LC is a diagnostic challenge.

- •

In patients presenting with diffuse, bilateral, asymmetric signal abnormalities in white matter, infiltrative lymphoma should be considered, especially if there is callosal involvement.

- •

Consider brain biopsy in rapidly progressive cognitive decline to allow earlier therapy for a potentially curable disease.

- •

Awareness of this rare disease and early biopsy are required for preventing a poor clinical outcome.

Intravascular Lymphoma

IVL was originally described in 1959 and designated as “angioendotheliomatosis proliferans systemisata.” Since then, it has been referred to as neoplastic angioendotheliosis, malignant angioendotheliomatosis, and angiotropic large-cell lymphoma.

IVL is a rare subtype of extranodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with a distinct presentation. Anatomically, it is characterized by proliferation of clonal lymphocytes within small vessels with relative sparing of surrounding tissues. The degree of sparing of surrounding tissues and absence of lymphoma cells in lymph nodes and reticuloendothelial system is a hallmark of the disease.

Epidemiology and risk factors

IVL is a rare disease with an incidence of less than 1 person per million. It has been described in patients ranging from 34 to 90 years of age with a median age of 70 years and occurs equally in women and men. There are no known risk factors for IVL.

Clinical features

IVL is heterogeneous in its clinical presentation and affects the small vessels in nearly every organ. Although IVL is a clonal proliferation of lymphocytes, it is uncommon to find significant adenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, or malignant cells in the peripheral blood. Absence of IVL in the traditional sites of presentation of lymphoma makes accurate and timely diagnosis difficult. Clinical symptoms depend on specific organ involvement, which most often includes the CNS and skin. Patients with CNS compromise present with focal sensory or motor deficits, generalized weakness, altered sensorium, rapidly progressive dementia, seizures, hemiparesis, dysarthria, ataxia, vertigo, and transient visual loss. Initial diagnoses of stroke, encephalomyelitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, vasculitis, and multiple sclerosis (MS) are often made and a diagnosis of IVL is often not established until autopsy.

Laboratory findings

Anemia, elevated lactate dehydrogenase, and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate are common laboratory abnormalities in IVL. A majority of studies have shown IVL absent in peripheral blood smears.

Imaging findings

The diffuse nature of brain involvement, with multifocal abnormalities, is reflected by its MR imaging appearance. MR imaging findings of IVL include the following.

Infarct-like lesions

Multiple, round or oval metachronous cortical or subcortical lesions that are hyperintense on T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images, some presenting with restricted diffusion suggestive of small vessel ischemia or demyelination ( Figs. 2 and 3 ). Although classically IVL is thought to remain strictly confined to vascular lumina in the CNS, parenchymal and callosal involvement may represent extravascular spread of tumor and may help suggest the diagnosis (see Figs. 2 and 3 ).

Infarct-like lesions correlate with commonly reported findings of multiple recent or resolving infarctions. The lesions may not enhance (see Fig. 3 D). Infarct-like lesions suggest that the tumor predominantly involves small arteries. This pattern was reported in 36% of patients with IVL who had brain MR imaging.

Nonspecific white matter lesions

Poorly defined nonspecific white matter lesions have been reported, especially in the periventricular areas, mimicking leukoaraiosis ( Fig. 4 ). Some investigators speculate that severe vascular infiltration by tumor cells leads to small vessel occlusion, ischemia, and infarction, which are responsible for these imaging findings.

Masslike lesions

Williams and colleagues noticed that intraparenchymal mass lesions have extensive vasogenic edema and mass effect contrary to the characteristic features of tumor cell infiltration predominantly in the vascular lumen. Nodular-enhancing lesions may disappear in follow-up MR imaging studies and be replaced by other enhancing lesions in other locations reflecting a dynamic behavior of IVL (see Fig. 4 J–O).

Meningeal enhancement

Meningeal enhancement is sometimes present in patients with IVL, although the nature of this finding is unclear. Severe meningeal inflammatory reaction with tumor cells has been demonstrated in post mortem examinations.

Hyperintense T2 lesions in the pons

T2 hyperintense lesions in the central pons without contrast enhancement or diffusion restriction have been reported. These lesions in the central pons exclude the pontine tegmentum and ventrolateral region and are similar to those of pontine osmolytic demyelination and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome or those from intracranial dural arteriovenous fistula with venous congestion.

Occlusion of capillaries causes diffuse white matter abnormal intensities. Some investigators speculate that the hyperintense pons lesions result from occlusion of capillaries.

A majority of cases of IVL present as CNS abnormalities, particularly with diffuse encephalopathy, and/or subacute progressive multifocal neurologic deficits and MR imaging findings that resemble vasculitis.

Lymphomatoid Granulomatosis

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis (LG) is a rare angiocentric, destructive lymphoproliferative disorder. It mainly involves the lungs followed by the skin and brain. Isolated CNS involvement is rare. When it affects the CNS, it is more commonly due to spread of systemic LG to the CNS. Although it may develop in the immunocompetent, LG is more common in the immune suppressed, including AIDS patients.

Clinical picture

Clinical features of CNS involvement are highly variable, including headache, seizure, blindness, cranial nerve palsies, hemiparesis, ataxia, spastic gait, dementia, and altered consciousness.

Imaging findings

LG presents diverse neuroimaging features, such as multiple punctuate or linear enhancement, ringlike enhancement, large mass lesions, and leptomeningeal and choroid plexus involvement. Multifocal T2 hyperintensities with linear or punctuate contrast enhancement are common ( Fig. 5 ) and thought to be due to the angiocentric and angiodestructive nature of the disease. The lesions typically involve the white matter and deep gray nuclei. Leptomeningeal and cranial nerve enhancement are also common.

MR imaging is more sensitive than cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis or flow cytometry for detecting CNS involvement from LG.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree