MR enterography is frequently ordered for patients with suspected small bowel disorders. In this article, disease-causing malabsorption, vasculitides, and some of the less common small bowel diseases are reviewed. The clinical presentations, diagnostic criteria, and imaging findings of these diseases are discussed. Because the imaging findings in several small bowel diseases are nonspecific and/or overlap, radiologists must correlate clinical data with imaging to develop a narrower differential diagnosis. The unique or characteristic findings in certain diseases are also emphasized.

Key points

- •

MR enterography plays a major role in the evaluation of patients with suspected small bowel disease and can be extremely helpful in guiding the next most appropriate step in the workup of patients.

- •

MR enterography may be able to diagnose clinically unsuspected small bowel disorders.

- •

Many diseases involving the small bowel produce nonspecific findings such as wall thickening and mural hyperenhancement.

- •

Radiologist familiarity with clinical aspects of small bowel diseases, small bowel and associated imaging findings, and potential complications is imperative to construct an accurate differential diagnosis.

Introduction

MR enterography (MRE) is frequently ordered for patients with suspected small bowel disorders. The most common indication is for the diagnosis and surveillance of Crohn disease, but many other diseases can involve the small bowel. Patients with suspected small bowel disease may present with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, gastrointestinal tract bleeding, and malabsorption prompting small bowel imaging. However, many patients may present with vague or nonspecific abdominal symptoms and MRE may be ordered to screen the entire abdomen including the small bowel. In this latter scenario, MRE may be able to diagnose clinically unsuspected small bowel disorders.

In this article, diseases causing malabsorption, vasculitides, and some of the less common small bowel diseases are reviewed. Space restrictions preclude an in-depth discussion of these entities; however, several excellent review articles are referenced for further reading. The clinical presentations, diagnostic criteria, and imaging findings of these diseases are discussed. Because the imaging findings in several small bowel diseases is nonspecific and/or overlap, radiologists must correlate clinical data with imaging to develop a narrower differential diagnosis. The unique or characteristic findings in certain diseases are also emphasized.

Etiologies

Several classification schemes have been derived for diseases of the small bowel, including based on underlying histopathology ( Box 1 ); however, because of the complexity of these diseases, significant overlap exists.

Edema and impaired drainage

Ischemia

Angioedema

Hypoproteinemia

Cirrhosis

Lymphangiectasis

Venous obstruction

Infection

Campylobacter

Yersinia

Salmonella

Giardiasis

Tuberculosis/mycobacterium avium infection

Clostridium difficile

Cryptosporidiosis

Cytomegalovirus

Whipple disease

Hemorrhage

Spontaneous

Ischemia

Trauma

Vasculitis

Amyloid

Inflammation

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug enteropathy

Radiation

Chemotherapy

Vasculitis

Immune mediated (Crohn disease, CeD, autoimmune, graft-versus-host disease)

Peritonitis

Infiltrative conditions

Amyloid

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis

Mastocytosis

Fibrosis

Crohn disease

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis

Amyloid

Radiation

Post-inflammatory

Neoplastic and cancer-related treatment

Lymphoma

Multifocal neuroendocrine

Metastases

Radiation

Chemotherapy-induced conditions

Graft-versus-host disease

Approach to bowel wall thickening

Many diseases involving the small bowel produce nonspecific findings such as wall thickening and mural hyperenhancement. Underdistension can mimic pathologic bowel wall thickening, resulting in false-positive interpretations and unnecessary workup and treatment. Because MR obtains multiple sequences over the course of the examination, the radiologist has the opportunity to assess peristalsis and various degrees of distension over time and to determine whether suspected areas of wall thickening persist or resolves with improved distension.

The list of potential etiologies involving the small bowel can be overwhelming and, when encountering a case with bowel wall thickening in clinical practice, it can be difficult to construct a refined differential diagnosis. Several approaches have been proposed, including a pattern-based approach to computed tomography (CT) scans, which can be translated for use with MRE. This approach evaluates the enhancement characteristics (degree/pattern); the degree, length, and symmetry of the bowel wall thickening; the segmental location of involvement; and any associated abnormalities. If using this approach with MRE, one must be aware that MRE is more sensitive to contrast enhancement and mild inflammation than is CT scanning and that mild inflammation may coexist in areas of fibrosis; this can result in a more stratified enhancement pattern on MR imaging in entities that typically seem to be more homogenous appearance on CT scans. An alternate approach uses a checklist of specific diseases that can be reviewed to determine if the imaging findings are consistent. Whichever approach is used, radiologist familiarity with the clinical aspects of these diseases as well as with small bowel and associated imaging findings and potential complications is imperative.

Guidance of patient workup

In many cases, imaging may not be able to determine a specific diagnosis, but can be extremely helpful in guiding the next most appropriate step in the workup of patients. Therefore, an accurate and concise differential diagnosis is critical. For example, laboratory testing may be appropriate for some patients (eg, suspected infection, ischemia, angioedema and celiac disease [CeD]). In other patients, imaging may be most helpful to guide endoscopic evaluation and biopsy (eg, suspected CeD, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, Crohn disease, and neoplasm). Notably, endoscopic evaluation is often negative and not helpful in submucosal disease processes, such as angioedema. Prompt referral to surgery for cases of suspected ischemia or definitive neoplasm can be aided by imaging. In benign self-limited etiologies, such and angioedema and infection, serial follow-up can be suggested for assessing the resolution of findings and excluding a chronic process that may need further evaluation.

Celiac disease

CeD is an immune-mediated enteropathy caused by gluten exposure in genetically susceptible individuals. The classic symptoms of steatorrhea, weight loss, pain, and failure to thrive are only seen in approximately one-third of individuals. Other presenting symptoms include iron deficiency anemia, premature osteoporosis, infertility, dermatitis herpetiformis, and miscellaneous conditions (dental abnormalities, arthritis, hyposplenism, selective IgA deficiency). A delay in diagnosis is common in patients with nonspecific or atypical symptoms; in these patients, imaging may be the first to suggest the diagnosis.

Screening for CeD can be performed using a celiac serology cascade. The definitive diagnosis is made with upper endoscopy and biopsy with clinical and histologic response to a gluten-free diet. The characteristic histologic changes are those of villous atrophy; however, this finding is nonspecific and can be seen with other disorders. Crypt hyperplasia and increased T lymphocytes are also present.

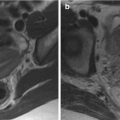

The imaging findings of CeD have been extensively reported. Many findings are nonspecific, but when seen can suggest the diagnosis and further workup. One of the earliest signs is small bowel dilatation ( Fig. 1 ) and increased small bowel fluid owing to both hypersecretion and malabsorption. Mild fold and wall thickening may be present secondary to decreased albumin, hypersecretion, inflammation, or superimposed complication (discussed elsewhere in this article). The reversal of the small bowel fold pattern is the most specific finding, but is often absent. Initially there is a decrease in the jejunal fold pattern (see Fig. 1 ) with subsequent increase in ileal folds termed “jejunization.” The duodenum may have a featureless appearance and submucosal fat may be present in the duodenum and proximal jejunum. Transient intussusceptions occur secondary to the dilated, atonic bowel and altered peristalsis ( Fig. 2 ). Multiple small mesenteric nodes are frequently present secondary to the chronic inflammation. Several other signs have also been reported.

Patients with known CeD who present with persistent or recurrent signs and symptoms and with villous atrophy despite more than 12 months of adherence to a gluten-free diet are considered to have refractory celiac. Refractory CeD is classified as type I or type II. Type II refractory CeD demonstrates clonal T-cell receptor rearrangement and abnormal immunophenotype of intraepithelial cells ; these patients have an increased prevalence of ulcerative jejunoileitis (UJ) and enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma. Patients with UJ present with fever, pain, distension, and weight loss. UJ occurs in up to 70% of patients with type II refractory CeD and is preneoplastic with up to 50% developing enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma.

MRE is helpful in evaluating patients with suspected refractory CeD. MRE can demonstrate resolution of findings in healed CeD and can detect bowel abnormalities, such as wall thickening, mural hyperenhancement, and mesenteric stranding or edema suggesting UJ ( Fig. 3 ). Given the variable distension of the jejunum on MRE, some prefer MR enteroclysis to improve jejunal distension if complications of CeD are clinically suspected. It may be difficult to differentiate UJ from lymphoma on imaging as both can present with areas of wall thickening and hyperenhancement ( Fig. 4 ). The presence of a more focal mass is suggestive of lymphoma ( Fig. 5 ).

Other complications that can develop in CeD include hyposplenism and cavitary mesenteric lymph node syndrome, which consist of lipid-rich hyaline-filled lymph nodes that have fat signal intensity and may demonstrate fat–fluid levels ( Fig. 6 ). These conditions usually occur in patients with severe uncontrolled CeD.

Whipple disease

Whipple disease is a rare multisystem disease, more common in middle-aged white males, which can involve the small bowel, heart valves, central nervous system, and joints. Potential bowel symptoms include weight loss, diarrhea (secondary to malabsorption), cramps, anorexia, and occasionally gastrointestinal bleeding. Whipple disease is caused by an infection with Tropheryma whipplei , which responds to antibiotic therapy; however, Whipple disease can be difficult to diagnose because of the atypical presenting symptoms. Without treatment, Whipple disease is ultimately fatal and even with treatment relapse occurs in up to 33%. The infection leads to a disorder in bacterial disposal resulting in macrophages with bacteria and abnormal lipid accumulation. This results in classically described lipid-laden periodic acid-Schiff–positive staining macrophages on histology.

The imaging findings include dilatation secondary to malabsorption and diffuse or patchy micronodules located in the proximal small bowel. However, because of the inferior spatial resolution of MRE compared with fluoroscopic barium examinations, this nodularity is usually not appreciated. On MRE, there may be bowel wall and fold thickening and the folds may appear somewhat nodular or bulbous ( Fig. 7 ). A unique association is the presence of fat-containing mesenteric lymph nodes.