Ovarian malignancy is the fifth most common cause of cancer death in women (after lung, breast, colorectal, and pancreatic cancers). Malignant lesions of the ovaries include primary and secondary neoplasms. Primary ovarian neoplasms are differentiated by the cell origin, including (1) surface epithelial cells, (2) germ cells, and (3) stromal cells. Approximately 90% of primary ovarian cancers are epithelial tumors, arising from the surface epithelium. Based on the degree of differentiation, ovarian tumors are divided into three major categories: well differentiated (10%), moderately differentiated (25%), and poorly differentiated (65%). Less-differentiated tumors are associated with worse prognosis. Primary fallopian tube carcinoma (PFTC) is a rare tumor that histologically and clinically resembles primary ovarian cancer.

Metastases to the ovaries are relatively uncommon, with the most common being from gastric carcinoma; colon, pancreatic, and breast cancers; and melanoma. Accurate distinction between primary and secondary tumors may be difficult.

Disease

Epithelial Ovarian Cancer

Epithelial ovarian cancer is separated into two major categories: invasive (80%) and noninvasive (borderline) tumors (20%), which are associated with different prognostic characteristics. Epithelial invasive tumors are further subdivided into five histopathologic groups: serous (50%), mucinous (20%), endometrioid carcinoma (15%), clear cell carcinoma (10%), and undifferentiated tumor (<5%). Brenner tumor is the only surface epithelial tumor that is almost invariably benign.

Serous Cystadenocarcinoma

Serous cystadenocarcinoma is a serous malignant tumor and is the most common type (50%) of epithelial cancer.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Malignant (25%) and borderline (15%) serous tumors are less common than benign serous tumors (60%) of the ovary. Malignant tumors predominantly involve perimenopausal and postmenopausal women, with the proportion of malignant neoplasms increasing with age; 13% of neoplasms in premenopausal women are malignant compared with 45% in the postmenopausal group. In addition, elderly postmenopausal women tend to be afflicted with poorly differentiated, more aggressive tumors.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

They present as thick-walled unilocular or septated cystic masses usually smaller than mucinous tumors with solid papillary projections; hence they are frequently referred to as papillary serous carcinoma . Benign serous lesions have fewer and smaller papillae on the internal surface of the cyst. Fifty percent of malignant tumors and 20% of benign serous tumors are bilateral. Serous tumors contain microcalcifications referred to as psammomatous bodies in up to 30% of cases and are commonly associated with carcinomatosis.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Patients commonly present with a pelvic mass, pelvic pain, or abdominal fullness or swelling resulting from mass or ascites. Constitutional symptoms include anemia and cachexia. Most patients present with advanced disease because of a lack of specific early symptoms and signs.

Imaging Indications and Algorithm

Ultrasound (US) is the common modality used to detect and characterize an adnexal mass. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), because of its better soft tissue contrast resolution and higher sensitivity to assess vascularity, can be used to further characterize the lesion if indeterminate with US. Computed tomography (CT) is most commonly used to stage advanced disease.

Imaging Technique and Findings

Ultrasound

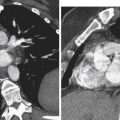

US shows an adnexal mass that is either unilocular or septated, often with thick walls and papillary or nodular projections on gray scale imaging ( Figure 30-1 ). The solid components can show vascularity with arterial and venous flow on Doppler interrogation. Absence of vascularity on Doppler US, however, does not exclude a vascular solid component (see Figure 30-1 ).

Computed Tomography

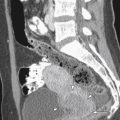

CT often shows low attenuation cystic adnexal mass with areas of scattered calcification and contrast enhancement of the solid components ( Figure 30-2 ).

Magnetic Resonance

MRI shows an adnexal cystic mass demonstrating predominantly low signal on T1-weighted sequences and high signal on T2-weighted sequences except for solid components that can be intermediate to high signal and uniform or heterogeneous in signal intensity (see Figures 30-1 and 30-2 ). The solid components show enhancement, helping to differentiate blood products or areas of necrosis from mural nodules and projections (see Figures 30-1 and 30-2 ).

Classic Signs

Classic signs of serous cystadenocarcinoma include bilateral thick-walled adnexal cystic lesions with solid components or papillary projections with ascites and peritoneal carcinomatosis.

Mucinous Cystadenocarcinoma

Definition

Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma is a mucinous malignant tumor and is the second most common type (20%) of epithelial cancer.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Malignant (5% to 10%) and borderline (10% to 15%) mucinous tumors are much less common than benign mucinous tumors (80%) of the ovary. Mucinous neoplasms are more commonly seen in an older patient population than serous adenocarcinoma, with a later peak age of 75 to 80 years.

Pathophysiology

These may be large, multiloculated masses. The cystic areas may have smaller honeycomb-like locules with thick walls and septae that contain mucinous material. Mucinous tumors are less likely to be bilateral and contain solid components, papillary projections, or linear calcifications than serous tumors. They can be associated with pseudomyxoma peritonei, although this is most commonly encountered in the context of mucinous adenocarcinoma of the appendix.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Patients commonly present with a pelvic mass, pelvic pain, or abdominal fullness and swelling as a result of mass or ascites. Constitutional symptoms include anemia and cachexia. Most patients present with advanced disease because of the lack of specific early symptoms and signs.

Imaging Technique and Findings

Ultrasound

US often shows a large adnexal mass that is a multiloculated, thick-walled cystic lesion containing material of different echogenicity in the cystic areas. Solid components or papillary projections on gray scale imaging, when present, can show vascularity on Doppler interrogation.

Computed Tomography

CT often shows a large low attenuation cystic adnexal mass with occasional high attenuation locules within as a result of high protein contents of mucinous material. There is contrast enhancement of the thick septae and solid components when present ( Figure 30-3 ). Cysts can rupture and cause pseudomyxoma peritonei with thick mucinous material in the peritoneal cavity, resulting in mass effect and scalloping of surfaces of the liver and spleen.

Magnetic Resonance

MRI shows a large adnexal cystic mass demonstrating predominantly low signal on T1-weighted and high on T2-weighted images, although signal intensity varies on both sequences depending on protein content of mucinous material. Solid components show intermediate signal intensity. The thick septae and solid components show enhancement.

Classic Signs

Classic signs of mucinous cystadenocarcinoma include large multilocular cystic adnexal masses that have thick walls and septae with variable appearance of contents of locules and compartments on different imaging modalities as a result of the variable protein content of mucin, with thick material causing scalloping of visceral surfaces.

Endometrioid Carcinoma

Definition

Endometrioid carcinoma is a proliferative endometrial tumor and is the third most common type (15%) of epithelial cancer after serous and mucinous cystadenocarcinomas.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

They are almost always malignant (80%) with the remainder being borderline malignant. Approximately 15% to 30% are associated with synchronous endometrial carcinoma or endometrial hyperplasia. Although rare, endometrioid carcinoma is the most common malignant neoplasm arising from endometriosis, followed by clear cell carcinoma. Endometrioid carcinomas usually present earlier than other ovarian cancers, particularly when associated with endometriosis, with approximately 15% of patients aged less than 45 years, 47% of patients between 46 and 64 years, and 38% of patients aged more than 65 years.

Pathophysiology

They are mixed solid and cystic adnexal masses similar to the other epithelial lesions. Most arise from epithelial surfaces, although some may arise from endometriotic cysts. In contrast to other epithelial tumors, they may occasionally be completely solid. Bilateral involvement is seen in 30% to 50% of cases. Associated abnormalities include endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma developing as independent primary tumor and coexisting endometriosis.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Patients commonly present with pelvic mass, pelvic pain, or abdominal fullness and swelling. Patients may also have postmenopausal vaginal bleeding. Constitutional symptoms include anemia and cachexia.

Imaging Technique and Findings

Ultrasound

US shows mixed solid and cystic adnexal mass often with areas of variable echogenicity as a result of solid, hemorrhagic, and necrotic areas. Color Doppler can help differentiate solid from hemorrhagic areas by showing vascularity with arterial and/or venous flow on Doppler interrogation. Lack of vascularity in a solid-appearing area on Doppler US does not exclude a vascular component.

Computed Tomography

CT shows a mixed solid and cystic adnexal mass, often with a predominant solid component that enhances, allowing differentiation from blood clot.

Magnetic Resonance

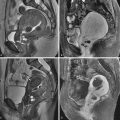

MRI shows a mixed solid and cystic adnexal mass demonstrating a low signal cyst with intermediate signal solid elements on T1-weighted images, and a high signal cystic lesion with heterogeneous solid component of variable signal intensity on T2-weighted images ( Figure 30-4 , A ). When a lesion arises within an endometrioma, the nodule may appear hypointense compared with otherwise high T1-weighted cyst content. With malignant transformation of an endometrioma, however, the cyst contents rarely show the typical low signal or shading on T2-weighted sequences of an endometrioma. A T1-weighted sequence with fat suppression can confirm that the background hyperintense T1 signal is not fat ( Figure 30-4 , B ). Contrast-enhanced images show marked enhancement of the solid nodules ( Figure 30-4 , C ) that are most clearly depicted on dynamic subtraction imaging.

Classic Signs

Endometrioid cancers are unilateral or bilateral mixed solid and cystic masses with cyst contents, which rarely show the typical low signal or shading on T2-weighted sequences of an endometrioma. There can be associated endometriosis, endometrial hyperplasia, and even concomitant endometrial carcinoma.

Clear Cell Carcinoma

Definition

Clear cell carcinoma is an epithelial tumor that can possess several characteristic cell types, with clear cells and hobnail cells being the most common.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Clear cell carcinomas represent approximately 5% to 10% of ovarian carcinomas and are always malignant. They are similar to clear cell carcinomas of the endometrium, cervix, and vagina but are not associated with exposure to diethylstilbestrol. The prognosis appears to be better than that of other ovarian cancers, probably because the majority (75%) of clear cell carcinomas present with stage I disease.

Pathophysiology

They are unilocular or large cystic lesions with solid nodules protruding into cystic component and thus resemble serous tumors. Clear cell carcinoma may develop in patients with endometriosis.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Patients commonly present with pelvic mass, pelvic pain, or abdominal fullness and swelling. Constitutional symptoms may include anemia and cachexia but are less common because of the slow growth of the tumor.

Imaging Technique and Findings

Ultrasound

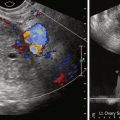

Common findings on US in clear cell carcinoma include a unilocular or large cyst with solid areas. The cyst margin is almost always smooth with solid areas that are often irregular ( Figure 30-5 , A ). The solid components commonly show vascularity on Doppler interrogation ( Figure 30-5 , B ). Although these findings are more likely to indicate a serous tumor, the differential diagnosis should include clear cell carcinoma.

Computed Tomography

Large, low attenuation cystic masses with enhancing irregular solid protrusions or nodules are seen ( Figure 30-5 , C ). Contrast enhancement helps to differentiate areas of hemorrhage from solid elements.

Magnetic Resonance

The masses have a cystic component with signal intensity on T1-weighted images varying from low to high, depending on the hemorrhagic component. High signal cystic and heterogeneous signal solid areas on T2-weighted images and enhancement of solid components on contrast-enhanced study are usually seen.

Classic Signs

Classic signs of clear cell carcinoma include large cystic adnexal lesions containing solid projections or nodules. Clear cell carcinoma should be included in the differential diagnosis when serous tumor is considered.

Undifferentiated Carcinoma

Definition

The cellular differentiation is not sufficient to categorize the tumor into one of the previously described groups, although small areas of various identifiable histologic elements may be seen in most lesions.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Undifferentiated tumors constitute less than 5% of ovarian neoplasms, and all are malignant. These lesions have the poorest outcome of any of the epithelial neoplasms and are often extensive at the time of presentation.

Pathophysiology

Pure undifferentiated carcinoma is rare, and most are probably serous or endometrioid carcinomas (these tumors frequently contain areas similar to those seen in undifferentiated malignant neoplasms).

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Presentation is often silent with no obvious signs or symptoms until late in course, with approximately two thirds of patients having extrapelvic disease at diagnosis. Constitutional symptoms include anemia and cachexia.

Imaging Technique and Findings

Ultrasound

Complex solid and cystic adnexal masses with thick walls, septae, and variable papillary projections are seen. Color Doppler can help visualize solid vascularized tissues and distinguish them from nonvascularized contents.

Computed Tomography

Mixed solid and cystic pelvic mass, often ill defined with extension into adjacent organs and structures, may be seen. The ovary may be difficult to visualize. CT provides information on potential resectability of locally invasive lesions.

Magnetic Resonance

These lesions usually appear as mixed solid and cystic lesions, with solid components showing low to intermediate signal and cystic components showing high signal on T2-weighted images. Nodular solid components are best identified on dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI.

Classic Signs

Classic signs of undifferentiated carcinoma include a large mixed solid and cystic pelvic mass, which has local invasion into adjacent organs and structures.

Brenner Tumor

Definition

Brenner tumor is a transitional tumor of the ovary comprising three types: benign, atypical proliferative, and malignant.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Brenner tumors represent approximately 2% to 3% of ovarian tumors and are rarely malignant. Brenner tumors are associated with other ovarian tumors in 30% of cases.

Pathophysiology

Microscopically, transitional epithelial cells within a prominent fibrous connective tissue stroma are seen. This histologic diagnosis is based on the demonstration of a residual benign Brenner histologic component within an otherwise malignant transitional cell tumor.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Brenner tumors are usually small (2 cm) and discovered incidentally, but affected patients may present with a palpable mass or pain.

Imaging Technique and Findings

Ultrasound, Computed Tomography, and Magnetic Resonance

Brenner tumors manifest as a multilocular cystic mass with a solid component or as a small, mostly solid mass. With CT the solid components of these masses are mildly or moderately enhanced. Using T2-weighted MRI, the dense fibrous stroma demonstrates low signal intensity similar to that of a fibroma. Extensive amorphous calcification is often present within the solid component.

Classic Signs

Findings are similar to ovarian fibromas. The presence of extensive amorphous calcification within a solid adnexal lesion is suggestive of Brenner tumor, whereas calcification is uncommon in fibromas.

Malignant Germ Cell Tumor

Tumors of germ cell origin are the second most common group of ovarian neoplasms, representing 15% to 20% of all ovarian tumors. This group of tumors includes mature cystic teratoma (benign), immature teratoma, dysgerminoma, endodermal sinus tumor, embryonal carcinoma, and choriocarcinoma. All the germ cell tumors except mature cystic teratoma are malignant but account for less than 5% of all malignant ovarian tumors.

Malignant Teratoma

Definition

Malignant teratomas tend to occur in two forms: primary immature teratoma and malignant transformation of a mature cystic teratoma. Immature teratomas, which have also been called embryonal, malignant, or solid teratomas, contain immature tissues that resemble those of the embryo.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Immature teratoma represents less than 1% of all ovarian malignancy and less than 1% of teratomas. They usually present during first 2 decades of life.

Malignant transformation occurs in less than 2% of mature cystic teratomas and tends to happen in postmenopausal women with large tumors.

Pathophysiology

Malignant, immature teratomas must be differentiated from benign mature cystic teratomas and have prominent solid components that may demonstrate internal necrosis or hemorrhage. Mature tissue elements from all three germ layers similar to those seen in mature cystic teratoma are invariably present, but the predominant tissue indicative of malignancy is primitive neuroectoderm. The overwhelming majority of mature cystic teratomas that undergo malignant transformation are squamous cell carcinomas, with adenocarcinoma and carcinoid tumors occurring infrequently.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation

Patients are commonly asymptomatic with palpable abdominal mass, and occasionally with acute abdominal pain resulting from torsion or hemorrhage. Immature teratomas are typically not associated with elevations of serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) levels, but approximately 50% of patients with these tumors have elevated α-fetoprotein (AFP) levels.

Imaging Technique and Findings

Ultrasound

Malignant teratomas present as a predominantly solid mass, although numerous cystic areas of varying size are commonly seen on US. Calcifications are usually present with resultant posterior acoustic shadowing. Whereas the calcification of the mature teratoma is typically localized to a mural nodule, the calcifications in the tissue associated with immature teratoma, however, are scattered throughout the tumor. They may contain hyperechoic areas within the mass, which may be secondary to fat or hemorrhage. Mature cystic teratomas that undergo malignant transformation may have solid areas that are not the typical hyperechoic solid-appearing areas of mature cystic teratomas (see Chapter 29 ).

Computed Tomography

Malignant teratomas typically appear as a large solid mass with slightly ill-defined borders, and contain low attenuation areas consistent with intralesional fat, enhancing solid elements, and high attenuation areas of scattered calcification ( Figure 30-6 , A and B ). Small quantities of fat and calcification are often better seen on CT than MRI.