Intercavernous sinuses

Inferior petrosal sinus

Superior petrosal sinus

Pterygoid plexus

Superior ophthalmic vein

Sphenoparietal sinus

Basilar venous plexus

Middle cerebral vein

Usually rapid fistula with arterial pressure of ICA transmitted to the CS and its venous drainage pathways.

Uncommon in developed world.

Cause

Traumatic

Majority follow severe head injury – e.g., skull base fracture or deep penetrating wound to the orbit (Fig. 1).

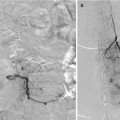

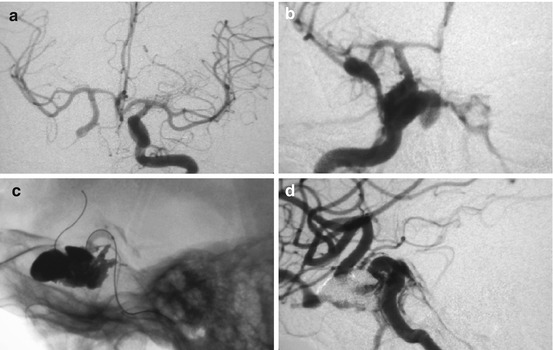

Fig. 1

Forty-three-year-old male with stabbing injury into left orbit showing a delayed presentation of a CCF and use of high-density Onyx® with balloon protection to partially treat the CCF which subsequently closed spontaneously. (a) Initial left ICA angiography shows retrograde flow in right ICA as the penetrating injury crossed the midline and occluded the right ICA; (b) Two weeks later a right CCF occurred as right ICA recanalized; (c) Microcatheter placed into CS via arterial route with ICA balloon protection; (d) Incomplete occlusion of CCF sufficient for later spontaneous occlusion

Signs of direct CCF may be masked and diagnosis delayed due to patient being obtunded with facial injuries and swelling or sometimes delay in fistula opening (Fig. 1).

Spontaneous

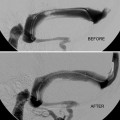

Usually acute presentation due to rupture of asymptomatic cavernous ICA aneurysm (Figs. 2 and 3)

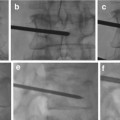

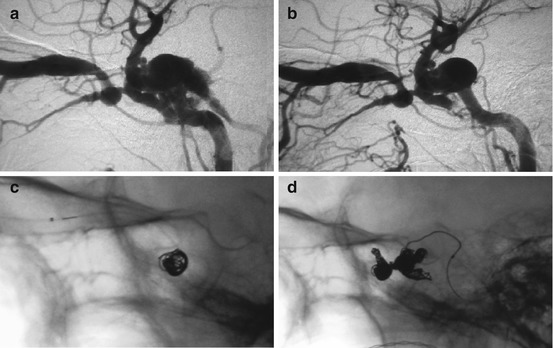

Fig. 2

Seventy-eight-year-old female with a CCF due to a ruptured cavernous ICA aneurysm demonstrating how angiography can change without treatment and how several routes of access to CS can be used to occlude a CCF. (a) Initial angiogram shows drainage of CS via SOV and IPS; (b) IPS drainage closed a few days later before treatment; (c) Initial transvenous coil embolization via SOV; (d) Further coil embolization of CS via arterial route through rent in ICA

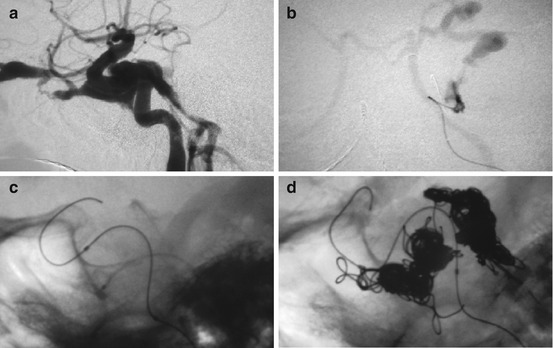

Fig. 3

Seventy-four-year-old female with a ruptured cavernous ICA aneurysm showing several venous routes into the CS, how balloon protection may be needed to retain coils, and that multiple treatments may be needed. (a) CS drainage via IPS and SOV; (b) Transvenous access to CS via IPS also showing SOV and facial veins; (c) Balloon protection of ICA during IPS coil embolization; (d) CCF reopened 3 days later and needed further coiling via IPS

May be underlying vascular disorder (e.g., Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, fibromuscular dysplasia, ICA dissection)

Rarely direct CCFs are slow flow with milder presenting features similar to a slow-flow indirect fistula (B, C, D) (Table 2)

Table 2

Barrow spontaneous carotid-cavernous fistula classification

Spontaneous carotid-cavernous fistulas are classified into the following groups

A. Direct high-flow shunt between ICA and cavernous sinus, often from ruptured cavernous ICA aneurysm

B. Indirect low-flow dural shunts between meningeal branches of the ICA and the cavernous sinus

C. Indirect low-flow dural shunts between meningeal branches of the ECA and the cavernous sinus

D. Indirect low-flow dural shunts between meningeal branches of both the ICA and ECA and the cavernous sinus

Another way to consider carotid-cavernous fistulas is by whether they are direct or indirect

Direct

Traumatic

Barrow Type A

Torn wall of cavernous carotid artery (collagen vascular disease)

Indirect

Barrow Types B–D

Clinical Presentation

Eye signs (most): proptosis, ophthalmoplegia, extraocular muscle congestion or cranial nerve palsy, chemosis, red eye, and visual loss (signs may be unilateral or bilateral)

Headache and bruit

Neurological deficit – cerebral hypoperfusion (arterial steal), intracranial hemorrhage, or edema (significant retrograde cortical veins causing venous hypertension)

Variable venous anatomy – CS often compartmentalized, e.g., ophthalmic veins may be isolated from fistulous point within CS – may be no eye signs despite high-flow fistula with cortical venous reflux, intracranial hemorrhage, or cerebral edema possible with no prior overt signs of fistula

Natural History

Usually progress to malignant lesion – often rapidly

Spontaneous resolution very unusual

Diagnostic Evaluation

Clinical

Clinical features of pulsatile proptosis, orbital congestion, ophthalmoplegia, visual loss, headache, raised intraocular pressures, and bruit strongly point to the diagnosis of a CCF (Table 3)

Table 3

Signs, symptoms, and radiological features of a direct carotid-cavernous fistula

Symptoms

Bulging eye

Double vision

Red eye

Headache

Visual loss

Facial numbness

Signs

Proptosis

Ophthalmoplegia

Chemosis

Reduced visual acuity

Dilated episcleral veins

Raised intraocular pressure

Cranial nerve palsy (CN 3–6)

Papilloedema

Radiological features on cross-sectional imaging

Proptosis

Orbital edema

Enlarged extraocular muscles

Dilated superior ophthalmic vein

Enlarged cavernous sinus

Full ophthalmological assessment – baseline eye movements, visual acuity, fundi, and intraocular pressures

Need high index of suspicion in head trauma patients

Laboratory

Routine blood tests including renal function, electrolyte profile, blood count, and coagulation profile

Imaging

Cross-Sectional Imaging (Computed Tomography (CT)/Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI))

Proptosis/orbital edema/engorged extraocular muscles

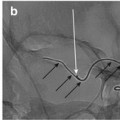

Enlarged superior ophthalmic vein (SOV) (Fig. 4)

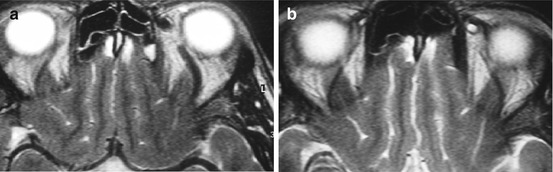

Fig. 4

MRI of 33-year-old female diabetic patient with an indirect CCF showing evidence of a CCF on cross-sectional imaging. (a) Dilatation of left SOV prior to treatment with a normal right SOV; (b) Left SOV appears normal after closure of CCF

Enlarged CS with engorgement of other venous connections to CS

Decreased caliber of the supraclinoid ICA

Rarely intracranial hemorrhage due to cortical venous reflux

CT or MR Angiography Shows Venous Anatomy

May show cavernous sinus/draining veins filling early to indicate presence of a fistula

Catheter Angiography (Gold Standard)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree