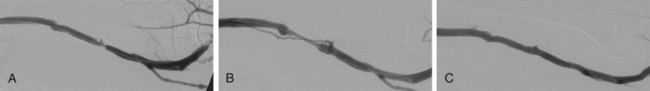

The criteria that define failing vascular access and the indications for percutaneous or surgical repair are described in the National Kidney Foundation (NKF) Clinical Practice Guidelines for Vascular Access.1 These criteria and indications have been incorporated into the Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR) quality improvement guidelines, the American College of Radiology (ACR)-SIR practice guidelines, and the SIR document on standards of reporting.1–3 Several clinical studies have reported that periodic assessment of intra-access blood flow may be the most reliable method for early detection of a developing stenosis.4–6 Intra-access blood flow is measured during hemodialysis, and if intra-access blood flow is less than 600 mL/min, a fistulogram is recommended to evaluate the entire vascular access circuit.1 Over time, there may be degeneration of graft material, resulting in overlying pseudoaneurysms. This is often due to fragmentation of the graft material from repeated cannulation and increased intragraft pressure from venous outflow stenosis.7 Treatment may be required when the pseudoaneurysm interferes with graft access or there are signs of impending rupture. Indicators for possible graft rupture include skin breakdown over the pseudoaneurysm or rapid pseudoaneurysm expansion. In severe cases or in the setting of graft infection, pseudoaneurysms are treated surgically. In patients with limited surgical options and in whom the anatomy is suitable, endovascular management may be considered. Early evaluation and intervention may be useful for salvage of nonmaturing fistulas.8 Recent reports demonstrate that serial dilation of small-diameter veins (balloon maturation) may expedite the maturation process and provide functionality to fistulas that may otherwise have failed.9–11 Although this indication for percutaneous intervention is not yet fully defined, AVFs that have failed to mature within 3 months of creation should undergo fistulography to determine whether angioplasty or surgical revision would be beneficial. The primary reasons for a fistula that fails to mature include vascular stenosis (outflow vein or arteriovenous anastomosis), competitive outflow veins, or a deep outflow vein that is nonpalpable. Management of vascular stenoses continues to be balloon angioplasty. Small competitive outflow veins can be managed by surgical ligation or endovascular embolization. Deep nonpalpable outflow veins require surgical revision. Use of stents or stent-grafts for management of failing hemodialysis grafts and fistulas remains controversial. Although angioplasty remains the primary technique for treating neointimal hyperplastic stenosis, stent placement may be indicated in specific situations. The Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) guidelines allow for stent use to treat central venous stenoses when there is (1) acute elastic recoil of the vein and over 50% residual stenosis after angioplasty and (2) stenosis that recurs within 3 months after previously successful angioplasty.1 When treating an aggressive recurring stenosis in a large central vein, a vascular stent may provide better results than angioplasty alone. Another acceptable use of stents is for acute repair of angioplasty-induced venous rupture. Although minor venous injuries can be effectively managed by prolonged inflation of an angioplasty balloon, more substantial injuries with continuing perivascular hemorrhage may require a stent or stent-graft to provide a more durable repair.12,13 Another important contraindication to percutaneous intervention is allergy to a contrast agent. Patients with a known or suspected allergy should be pretreated according to standardized protocols before fistulography or any interventional procedure requiring use of intravascular contrast material. Alternatively, a noniodinated contrast agent (e.g., CO2) may be used.14 For the relevant venous anatomy, please refer to Chapters 30 and 82. The majority of patients referred for fistulography will have at least one significant lesion requiring percutaneous intervention. Ideally the initial entry site into the vascular access should be chosen to provide a favorable route for subsequent interventional procedures. Once identified, the character, extent, and hemodynamic significance of each lesion should be assessed before proceeding with a percutaneous intervention. Multiple angiographic images obtained in different imaging planes are often necessary to thoroughly evaluate a stenosis before proceeding with percutaneous treatment. When measured on a two-dimensional angiographic image, a 50% luminal stenosis corresponds to a 75% to 80% decrease in cross-sectional area and is considered hemodynamically significant.15 The fistulogram may also demonstrate the presence of venous collateral channels adjacent to a stenosis, a finding indicative of significant obstruction. The hemodynamic significance of a stenosis can be difficult to determine with angiographic imaging alone.16 Quantitative measurements can be performed during the procedure, both before and after intervention, to ascertain a lesion’s hemodynamic significance. Pullback pressure measurements can be used to measure the transstenotic pressure gradient: a mean pressure gradient above 10 mmHg represents hemodynamically significant stenosis.17 Intraprocedural measurement of intra-access blood flow using specialized thermodilution catheters can also provide quantitative hemodynamic information.18 This technique is particularly useful for assessing the functional significance of complicated or multifocal stenoses. When performing fistulography, it is important to distinguish between fixed stenoses and venous spasm. Venous spasm typically appears as a long, smoothly tapered stenosis in a native vein, often at or near the point of access. Administration of a vasodilator drug (e.g., nitroglycerin) directly into the abnormal venous segment may help differentiate venous spasm from fixed stenosis. Venous spasm will often resolve after vasodilator administration, whereas a true stenosis will persist (Fig. 115-1).

Management of Failing Hemodialysis Access

Indications

Contraindications

Technique

Anatomy and Approach

Technical Aspects

Fistulography

Management of Failing Hemodialysis Access