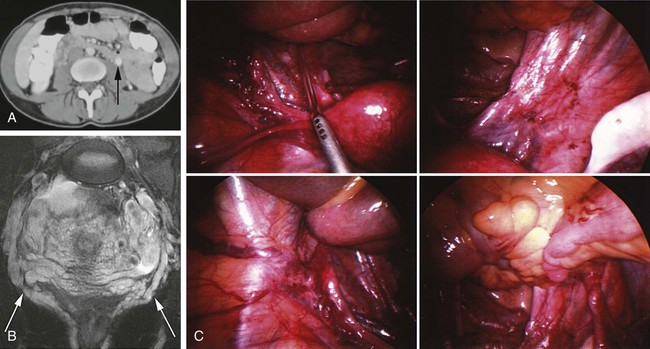

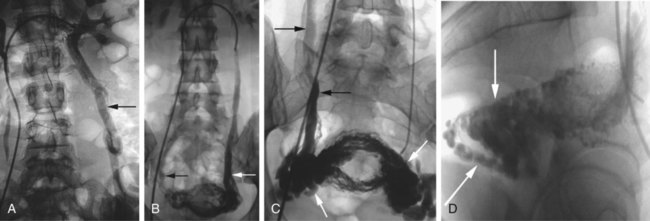

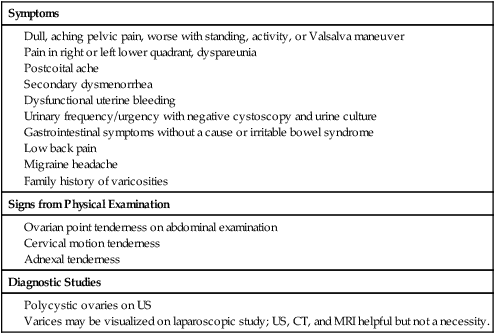

Darren D. Kies, Judy M. Lee, Anthony C. Venbrux and Hyun S. Kim Chronic pelvic pain, characterized by non-cyclic pelvic pain for longer than 6 months, is a common medical problem among women.1 The condition is potentially debilitating, and it afflicts millions of women worldwide. It has been reported that up to 39.1% of women have suffered chronic pelvic pain at some period in their lives.2 Pelvic congestion with pelvic varices has been the focus of clinical and research interests for many years since its first description by Richet in 18573 and its first association with chronic pelvic pain by Taylor in 1949.4 Physical symptoms of pelvic congestion causing chronic pelvic pain have been well documented,5 but with no clear consensus in diagnosis and treatment. Common therapies for pelvic congestion include medroxyprogesterone acetate (Provera [Pfizer Inc., New York, N.Y.])6 and goserelin (Zoladex [AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, Wilmington, Del.])7 to suppress ovarian function, and hysterectomy with or without bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (TAH/BSO).8 Despite its curative intent, hysterectomy studies reported residual pain in 33% of patients and a 20% recurrence rate.8,9 To improve clinical efficacy and reduce peri- and postoperative morbidity, percutaneous pelvic vein embolization treatment has been introduced. Venogram and embolization are indicated for patients who are suffering from chronic pelvic pain, and pelvic congestion is suspected to be the cause of the pain. Symptoms and signs of pelvic congestion have been well documented,5,10 but because several symptoms can overlap with those of other conditions, the diagnosis can be overlooked. The diagnosis of pelvic varices can be challenging even with advanced imaging studies such as ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT) (Fig. 80-1, A), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 80-1, B). Even with direct visualization with laparoscopic evaluation, the diagnosis can be missed in up to 80% of patients10 (Fig. 80-1, C). Thus, thorough clinical evaluation is imperative. Affected patients are typically in their late 20s or early 30s. Pelvic congestion with varicosities in the infundibulopelvic and broad ligaments draining via ovarian and internal iliac vein tributaries can cause dull, aching, unilateral pain in the pelvis. The pain can be worsened by walking and postural changes. It can be cyclic with dysfunctional bleeding and dysmenorrhea, or accompanied by dyspareunia or postcoital ache that may last for hours or days5,11 (Table 80-1). TABLE 80-1 Signs and Symptoms of Chronic Pelvic Pain Suggestive of Pelvic Congestion CT, Computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; US, ultrasound. From Beard RW, Reginald PW, Wadsworth J. Clinical features of women with chronic lower abdominal pain and pelvic congestion. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1988;95:153–61. Diagnostic criteria for pelvic varices on venogram include 5 mm or greater diameter of the ovarian vein, uterine vein, and utero-ovarian arcade; free reflux in the ovarian vein, with incompetence of the valve; filling of contrast material across midline; vulvar or thigh varices; and stagnant clearance of contrast material from the pelvic veins.10,12,13 For optimal visualization of ovarian vein incompetency and pelvic varices, a direct venogram of the renal veins, preferably selective ovarian venograms, should be performed. After informed consent, the patient is prepared and draped for a sterile procedure. Moderate conscious sedation is employed and intravenous (IV) antibiotic with gram-positive coverage is administered. Similar to diagnostic venography and embolotherapy procedures for male varicocele,14 diagnostic venography is performed via a transfemoral or transjugular approach. We prefer the transfemoral approach. The common femoral vein is accessed using the Seldinger technique and an 18- or 21-gauge single-wall needle. A 7F vascular sheath (Cordis Corp., Miami Lakes, Fla.) is placed in the right femoral vein, and a 7F Hopkins-customized guiding catheter (Cordis Corp.) is advanced into the left renal vein, pointing to the origin of the left ovarian vein. A left renal venogram is performed through the guiding catheter (Fig. 80-2, A). The left ovarian vein is selected with a 4F or 5F Glide Bentson-Hanafee-Wilson JB-1 or hockey stick–shaped catheter (Terumo Medical, Somerset, N.J.) over a 0.035-inch-diameter Glidewire (Terumo Medical), and a proximal left ovarian venogram is performed by hand-injection using iodinated contrast (Fig. 80-2, B). Performance of the Valsalva maneuver in an attempt to increase intraabdominal pressure and accentuate the pelvic varices may be useful. In our experience, variable duplex waveforms of the pelvic veins are seen with the Valsalva maneuver in patients with pelvic congestion syndrome (PCS).13 We perform venography and embolization with the patient supine for the needs of conscious sedation. After confirming incompetence of the valves in the left ovarian vein, the hydrophilic-coated catheter is further advanced to the distal ovarian vein over the Glidewire. Once the catheter is advanced to the pelvic level, a distal ovarian venogram is performed (Fig. 80-2, C and D

Management of Female Venous Congestion Syndrome

Clinical Relevance

Indications

Symptoms

Signs from Physical Examination

Diagnostic Studies

Technique

Anatomic Aspects

Technical Aspects

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Management of Female Venous Congestion Syndrome