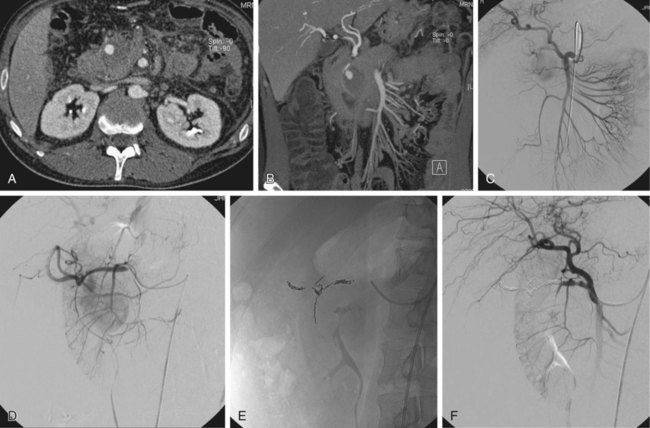

False aneurysms (pseudoaneurysms) of the visceral arteries represent an area of contained hemorrhage and are relatively uncommon but at high risk of rupture, with subsequent acute gastrointestinal or retroperitoneal hemorrhage. They always require treatment regardless of their size. Many are related to acute or chronic pancreatitis but may also occur after surgery or without an obvious cause. There should be a high index of suspicion for the presence of a pseudoaneurysm in a patient with a history of pancreatitis in whom upper gastrointestinal bleeding subsequently develops, although other causes (e.g., segmental portal venous hypertension secondary to splenic venous occlusion or unrelated peptic ulceration) are still more likely. However, if the episodes of hemorrhage in such patients are related to severe epigastric pain radiating to the back, a pseudoaneurysm communicating with the pancreatic duct and causing hemosuccus pancreaticus is likely.1 All visceral artery pseudoaneurysms require treatment, and the vast majority can be managed successfully by embolization, which should be the procedure of first choice.2–4 Surgery should be reserved for patients in whom complex anatomy precludes an endovascular approach. Indications for treatment of true visceral artery aneurysms are less clear-cut because prospective data on the risk of rupture are lacking. The splenic artery is the vessel most frequently involved, and aneurysms, when present, are commonly related to branch origins. Those less than 2 cm in size can probably be ignored. The American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association guidelines for management of patients with peripheral arterial disease5 conclude that: 1. “Open repair or catheter-based intervention is indicated for visceral aneurysms measuring 2.0 cm in diameter or larger in women of childbearing age who are not pregnant and in patients of either gender undergoing liver transplantation.” 2. “Open repair or catheter-based intervention is probably indicated for visceral aneurysms measuring 2.0 cm in diameter or larger in women beyond childbearing age and in men.” Although few would disagree with the first of these guidelines, the wording of the second is less helpful. There are undoubtedly patients in whom an asymptomatic visceral artery aneurysm measuring up to 2.5 cm in size is found on imaging performed for other reasons and can be managed conservatively. Indeed, some authors suggest that 2.5 cm rather than 2 cm should be the size above which therapy is required.6 There is no doubt, however, that symptomatic aneurysms or those that show a gradual increase in size on follow-up will require treatment. An additional indication for treatment of renal artery aneurysms is renovascular hypertension. Thorough knowledge of conventional and variant visceral arterial anatomy is essential, as is recognition of the many collateral pathways that can develop via normal anastomoses in response to visceral artery occlusive or stenotic disease.7 This rich collateral supply to most of the abdominal viscera means that embolization of major visceral vessels can often be performed without causing organ infarction. Lack of appreciation of the extent of this collateral network can, however, result in failure of endovascular therapy. For example, a pseudoaneurysm involving a right hepatic artery branch should be definitively treated by placing embolization coils on either side of the arterial defect to exclude it completely from the circulation. An angiographer who fails to recognize that intrahepatic arterial branches will receive a collateral supply from several possible sources (e.g., other hepatic, internal mammary, and inferior phrenic arteries) immediately after proximal hepatic artery occlusion is more likely to perform an inadequate embolization by placing coils only proximal to the pseudoaneurysm neck. Multislice computed tomography (CT) performed during the arterial phase of contrast medium enhancement will usually provide exquisite images, in a variety of planes, of both true and false aneurysms, which can be of great help in documenting the anatomy and planning endovascular therapy (Fig. 73-1). Most visceral arterial aneurysmal disease that requires therapy will be approached via a common femoral artery puncture. Occasionally an axillary or brachial artery approach will provide a more favorable route, such as when the aneurysmal disease involves a superior mesenteric artery that has a very acute origin from the aorta, or when there is marked compression of the origin of the celiac axis by the median arcuate ligament of the hemidiaphragm. It is essential that high-quality diagnostic angiographic images be obtained to document completely the anatomy of the diseased segment of the vessel so that treatment is successful. Considerable experience is necessary to routinely acquire high-quality diagnostic images of the visceral arteries. Unfortunately, it is increasingly difficult to obtain sufficient experience, because the indications for visceral angiography have decreased substantially over the last decade as alternative noninvasive imaging studies and ready access to endoscopy have become available. It is not the purpose of this chapter to discuss the technique of diagnostic visceral angiography, but it is such an important part of the procedure that some of the most useful technical points will be mentioned briefly. Interested readers are referred to other texts for a more detailed description.8 This technique, which is most easily performed by placing metallic coils on either side of the arterial defect (Figs. 73-2 to 73-4; also see Fig. 73-1

Management of Visceral Aneurysms

Indications

Technique

Anatomy and Approach

Technical Aspects

Visceral Angiography

Embolization

False Aneurysms (Pseudoaneurysms)

Embolization of the Diseased Vessel on Either Side of the Arterial Defect

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree