MANDIBLE AND MAXILLA: NONODONTOGENIC TUMORS AND CYSTS

KEY POINTS

- Computed tomography and cone beam volume computed tomography can be relatively specific in the diagnosis of mandibular masses given an organized approach that considers both odontogenic and nonodontogenic tumors and cysts.

- The mandible is much more likely to be involved by some of these tumors and cysts than the maxilla.

- Cystic varieties of these lesions without an identifiable matrix usually cannot be distinguished from one another.

- Enucleation and curettage is suitable definitive therapy for some of these lesions, and precise imaging is required for medical decision making if a gross bony margin must be recommended for adequate surgical management.

- In malignant tumors, imaging should include an assessment of perineural spread and sometimes regional lymph node spread and distant disease even though those risks tend to be low.

JAW MASSES: AN ODONTOGENIC VERSUS NONODONTOGENIC ORGANIZATIONAL FRAMEWORK

Mandibular and maxillary masses or those that clearly arise from the region of the dental arches can be organized into those of odontogenic origin (Chapter 99) and nonodontogenic origin, considered in this chapter. This differentiation aids in radiographic evaluation and subsequent medical decision making.

The nonodontogenic lesions may then be divided into cystic and solid groups. Nonodontogenic cysts are either mainly or not epithelial lined. The solid group may demonstrate a mineralizing matrix. Tumors and cysts of nonodontogenic origin may come from one of several cell lines that occupy and/or form the mandible and maxilla and their neurovascular constituents. The “occupying cells” are largely those that reside in the marrow space and maintain bone or provide support; however, some may travel there and populate from another source. The differential diagnosis of these masses then proceeds from a simple exercise in remembering the cells/tissues that can be the source of the pathologic condition or react to a pathologic state and what diseases can travel by the vascular system to the mandible and maxilla. Virtually all of these entities are discussed in Section II of this text. They will be treated in summary form in a following section for convenient reference.

Fibro-osseous lesions are a crossover group and can be of either odontogenic or nonodontogenic origin. The discussion of those entities is contained in Chapters 40, 91, and 99.

GENERAL PATTERNS OF DISEASE

The general growth patterns and imaging appearance of primary bone tumors and the variety of other potential nonodontogenic jaw lesions are discussed in detail in Chapters 25 through 30 and 35 through 42. The dental-related tumors and cysts discussed in Chapter 99 share many of the growth characteristics of the more benign gamut of these tumors.

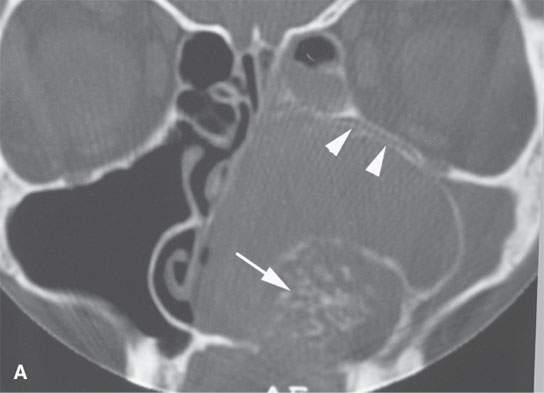

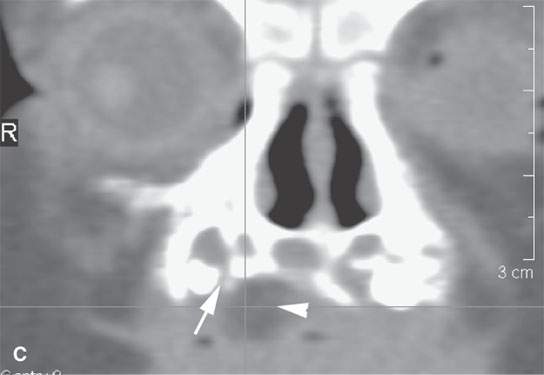

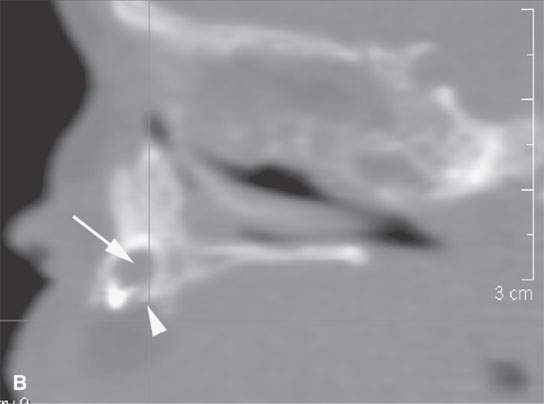

FIGURE 100.1. Two patients with lesions not of dental origin that could be considered of that origin. A: Patient 1 has a matrix-producing tumor arising from the alveolar ridge. The matrix appears to be distinctly chondroid (arrow), and the origin of the lesion can be seen to be from the dental arch based on the displacement of the bone of the maxillary alveolar ridge seen as separate (arrowheads) from the orbital floor. Final diagnosis was chondrosarcoma rather than a matrix-producing dental lesion. B, C: Patient 2 presenting with an abnormal mass in the region of the premaxilla. In (B), the sagittal reformation shows a normal tooth bud (arrow) and some remodeling of the alveolar ridge (arrowhead) in the region of the premaxilla. In (C), the coronal reformation shows the area of remodeling (arrow) associated with accumulation of fat (arrowhead) correctly identifying this as a small teratoma.

In general, benign or low-grade malignant jaw cysts and tumors will range from a unilocular “cystic expansile” appearance to a multilocular, septated mass sometimes with an identifiable mineralized matrix or rarely other specific features that strongly suggest the source (Fig. 100.1). The odontogenic lesions are sometimes related to unerupted or impacted teeth in a predictable manner as discussed in Chapter 99. The benign or low-grade malignant nonodontogenic lesions tend to have a narrow zone of transition and bulge rather than infiltrate into surrounding tissues; thus, their basic appearance suggests a lesion of low biologic activity (Fig. 100.2). This accurately reflects the behavior of the majority of these lesions. A more aggressive appearance with increasingly broader zones of transition and soft tissue infiltration pushes the differential diagnosis to a more malignant nonodontogenic gamut and one that also includes focal infectious and noninfectious inflammatory diseases (Figs. 100.3–100.5). This difference in morphology suggesting lower or higher biologic activity is a natural dividing line in considering the most likely nature and cause of a nonodontogenic tumor or cyst. Such deliberations can help direct the most appropriate next step in the patient’s evaluation.

Primary malignant tumors of the mandible tend to recur locally if not excised with an adequate margin, with some potential to produce regional lymph node disease or manifest perineural spread or distant metastases depending on the exact histology (Fig. 100.4). Other malignant mandibular tumors are likely to be metastatic or due to a systemic malignant process (Fig. 100.6). A primary masticator space malignancy with bony invasion is also possible (Chapter 145). In the maxilla, such a lesion may be due to a primary sinonasal, oral cavity, or buccal space cancer.

Since these nonodontogenic tumors have a potential full range of biologic activity, they may show intratumoral regressive changes such as hemorrhage and necrosis.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The variety of clinical presentations of jaw masses often raises the possibility of lesions that arise outside the jaw. It is often imaging that sorts out the more ambiguous of these situations. They include the following:

- An asymptomatic mass, usually submucosal and seen by the patient, patient associate, or health care provider

- Malocclusion or disordered mastication

- Jaw and/or temporomandibular joint or other facial pain and possibly trismus or otalgia and V2 or V3 sensory deficits or formications

- A cheek, parotid, or submandibular region mass

- Devitalization of teeth

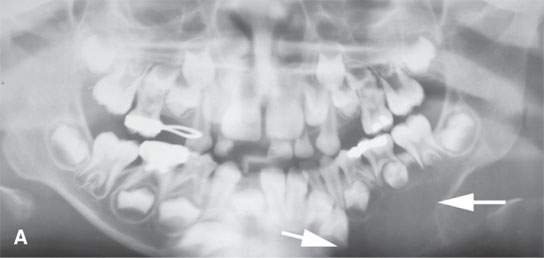

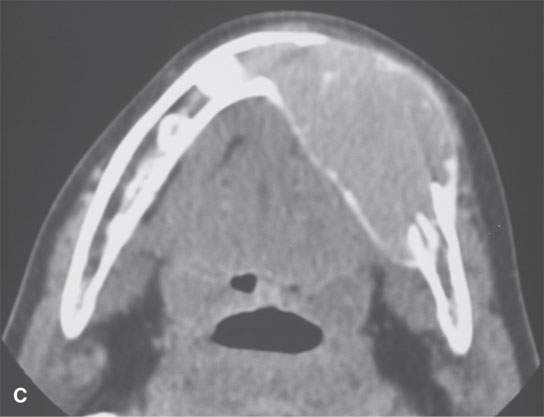

FIGURE 100.2. A patient presenting with a mass in the left lower jaw region. A: Panoramic views showing this to be a cystic expansile type of mass (arrows) not obviously associated with the dentition. B: Bone windows showing the expanded dehiscent bone of the mandibular body. C: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showing the mass to be solid and enhancing. Even though this is unilocular, ameloblastoma would be a primary diagnostic consideration. This proved to be a giant cell tumor.

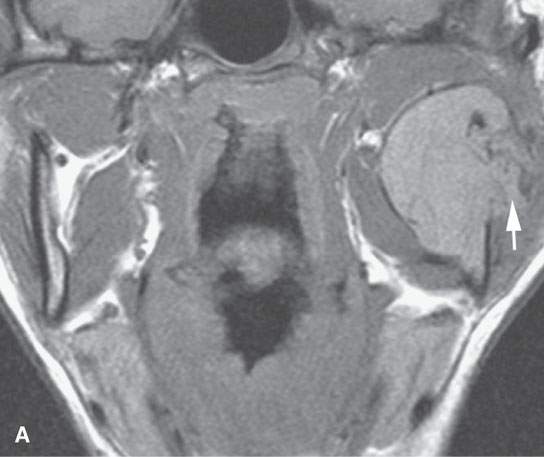

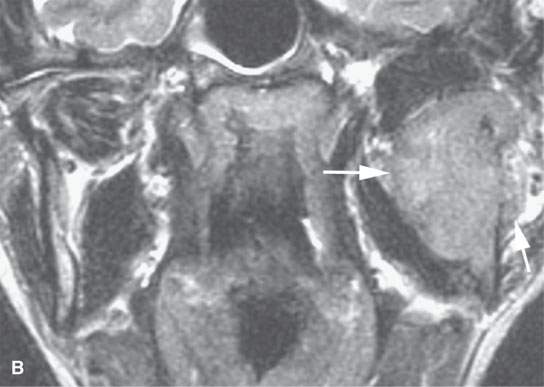

FIGURE 100.3. A patient presenting with a parotid region mass. A: Magnetic resonance imaging showing that the lesion is centered around the mandible with an infiltrating mass invading surrounding soft tissues (arrow). B: T2-weighted image showing the mass to be invasive at its margin (arrows) and centered in the mandible. Computed tomography–guided biopsy confirmed a plasmacytoma.

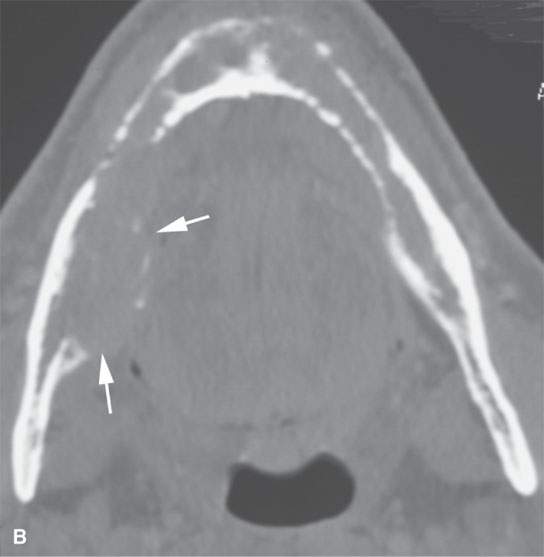

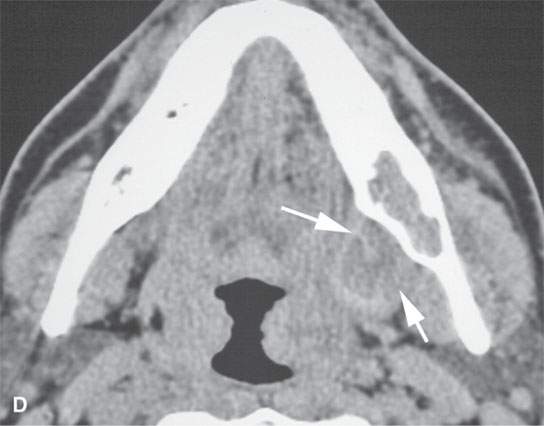

FIGURE 100.4. Two patients presenting with mandibular pain. A, B: Patient 1. In (A), computed tomography shows an infiltrating process with a fairly wide zone of bony transition involving the entire mandible. The marrow space of the mandible is replaced, and there is evidence of infiltration of soft tissues (arrows). In (B), the widely infiltrating process is most prominent in the area of the right retromolar trigone where it breaks out into surrounding soft tissues, but the entire marrow space is obviously replaced. (NOTE: Initial diagnostic consideration was lymphoma. Biopsy showed this to be an infiltrating adenoid cystic carcinoma, likely beginning in the right retromolar trigone and spreading within the marrow space and perineural within the mandible, mimicking the systemic malignancy. C, D: Patient 2. In (C),a fairly well-circumscribed mass is present in the region of the left retromolar trigone with a very narrow zone of transition. Normally, a dentigerous type of lesion would be considered most likely. In (D), however, there is also an obviously infiltrating mass in the adjacent peripharyngeal space (arrows). There is also a single 15-mm metastatic lymph node in level 2. These changes were due to mucoepidermoid carcinoma arising from minor salivary gland tissue beneath the mucosa of the retromolar trigone region. No mucosal mass was present. (NOTE: These two cases illustrate that nonodontogenic masses can present with a wide range of morphologic aggressiveness and in some cases mimic odontogenic lesions as those seen in Patient 2). In reality, in the vast majority of mandibular mass cases, biopsy is the next step after imaging.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree