Lymph Node Groups

Mediastinal lymph nodes are generally classified by location. Most descriptive systems are based on a modification of Rouvière’s classification of lymph node groups. The names used in describing lymph nodes groups for the purpose of lung cancer staging may differ and are reviewed in Table 4.1 .

| IASLC Nodal Zones | ATS Description | ATS Station |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Right upper paratracheal | 2R |

| Left upper paratracheal | 2L | |

| Prevascular | 3 | |

| Right lower paratracheal | 4R | |

| Left lower paratracheal | 4L | |

| Subaortic | 5 |

| Paraaortic | 6 | |

| Subcarinal | 7 |

| Paraesophageal | 8 |

| Pulmonary ligament | 9 | |

| Hilar | 10 |

| Interlobar | 11 | |

| Lobar | 12 |

| Segmental | 13 | |

| Subsegmental | 14 |

Anterior Mediastinal Nodes

Internal mammary nodes are located in a retrosternal location near the internal mammary artery and veins ( Fig. 4.1 ). They drain the anterior chest wall, anterior diaphragm, and medial breasts.

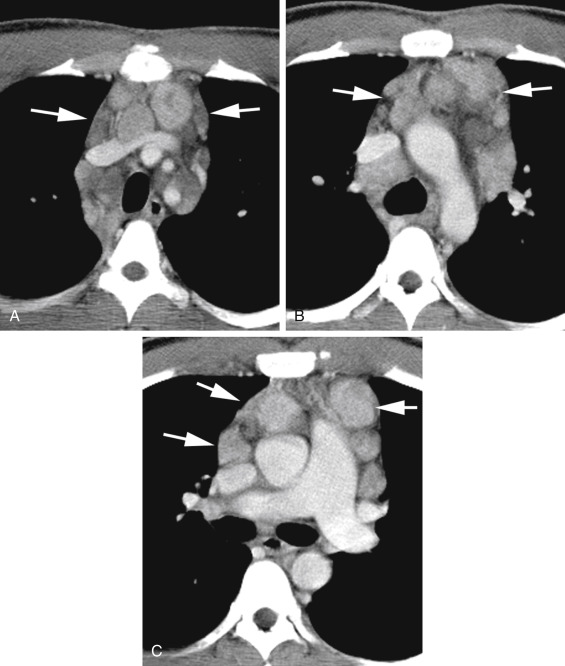

FIG. 4.1

Internal mammary lymph node enlargement in sarcoidosis.

Bilateral internal mammary nodes (large arrows) are enlarged, as are pretracheal (PT) and prevascular (PV) nodes.

Paracardiac nodes (diaphragmatic, epiphrenic, and pericardial) surround the heart on the surface of the diaphragm and communicate with the lower internal mammary chain ( Fig. 4.2 ). Like internal mammary nodes, they are most commonly enlarged in patients with lymphoma and metastatic carcinoma, particularly breast cancer.

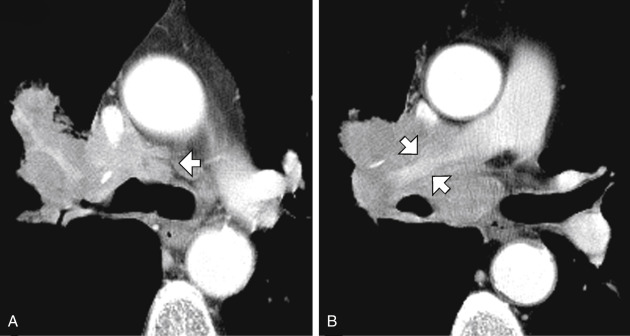

FIG. 4.2

Paracardiac node enlargement.

In a patient with Hodgkin lymphoma, enlargement of the paracardiac nodes (large arrows) is visible. These lie anterior to the pericardium (small arrows) .

Prevascular nodes lie anterior to the great vessels ( Figs. 4.1, 4.3, and 4.4A ). They may be involved in a variety of diseases, notably lymphoma, but their involvement in lung cancer is less common.

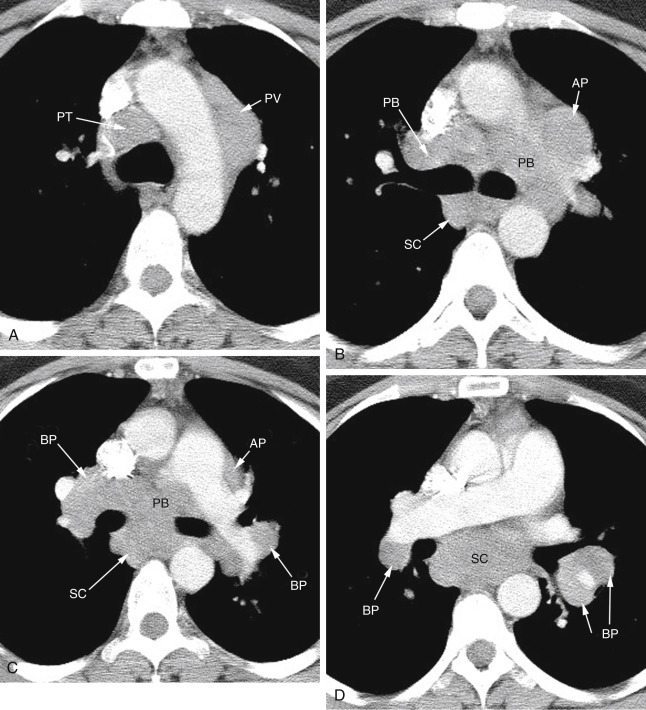

FIG. 4.3

Prevascular lymph node enlargement in hodgkin lymphoma.

Enlarged prevascular (anterior mediastinal) lymph nodes (arrows) are seen anterior to the brachiocephalic veins and aortic branches (A), anterior to the aortic arch and superior vena cava (B), and anterior to the superior vena cava, aortic root, and main pulmonary artery (C). Enlarged pretracheal lymph nodes are also visible in (A) and (B). Some nodes appear low in attenuation and are probably necrotic.

FIG. 4.4

Lymph node enlargement in a patient with sarcoidosis.

(A) At the aortic arch level, enlarged pretracheal (PT) and prevascular (PV) nodes are visible. (B) At the level of the tracheal carina, aortopulmonary (AP) lymph nodes lie lateral to the left pulmonary artery. Lymph nodes adjacent to the main bronchi are termed peribronchial (PB) . Subcarinal (SC) lymph nodes are located posterior to the carina. (C) At a lower level, aortopulmonary (AP) , peribronchial (PB) , and subcarinal (SC) nodes are again visible. Hilar lymph nodes are termed bronchopulmonary (BP) . (D) Below (C) large subcarinal (SC) and bronchopulmonary (BP) nodes are again visible.

Middle Mediastinal Nodes

Lung diseases (e.g., lung cancer, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, and fungal infections) that secondarily involve lymph nodes typically involve middle mediastinal lymph nodes.

Pretracheal or paratracheal nodes occupy the pretracheal (or anterior paratracheal) space ( Figs. 4.1, 4.3, and 4.4A ). These nodes form the final pathway for lymphatic drainage from most of both lungs (except the left upper lobe). Because of this, they are commonly abnormal regardless of the location of lung disease.

Aortopulmonary nodes are considered by Rouvière to be in the anterior mediastinal group, but they serve the same function as right paratracheal nodes ( Figs. 4.3C and 4.4B and C ). The left upper lobe is drained by this node group.

Subcarinal nodes are located in the subcarinal space, between the main bronchi ( Fig. 4.4B–D ), and drain the inferior hila and both lower lobes. They communicate in turn with the right paratracheal chain.

Peribronchial nodes surround the main bronchi on each side ( Fig. 4.4B and C ). They communicate with bronchopulmonary (hilar; Fig. 4.4C and D ), subcarinal, and paratracheal nodes.

Posterior Mediastinal Nodes

Paraesophageal nodes lie posterior to the trachea or are associated with the esophagus, or both ( Fig. 4.5 ). Subcarinal nodes are not included in this group.

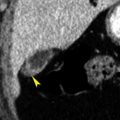

FIG. 4.5

Paraesophageal lymph node enlargement in metastatic testicular carcinoma.

Large lymph nodes on the right (large arrow) can be considered paraesophageal or inferior pulmonary ligament nodes. They appear inhomogeneous and are necrotic. An enlarged left paravertebral lymph node (small arrows) is also visible posterior to the aorta.

Inferior pulmonary ligament nodes are located below the pulmonary hila, medial to the inferior pulmonary ligament. On CT, they are usually seen adjacent to the esophagus on the right and the descending aorta on the left. Below the hila, they are difficult to distinguish from paraesophageal nodes. Together with the paraesophageal nodes, they drain the medial lower lobes, esophagus, pericardium, and posterior diaphragm.

Paravertebral nodes lie lateral to the vertebral bodies, posterior to the aorta on the left ( Fig. 4.5 ). They drain the posterior chest wall and pleura. They are most commonly involved, together with the retrocrural or retroperitoneal abdominal nodes, in patients with lymphoma or metastatic carcinoma.

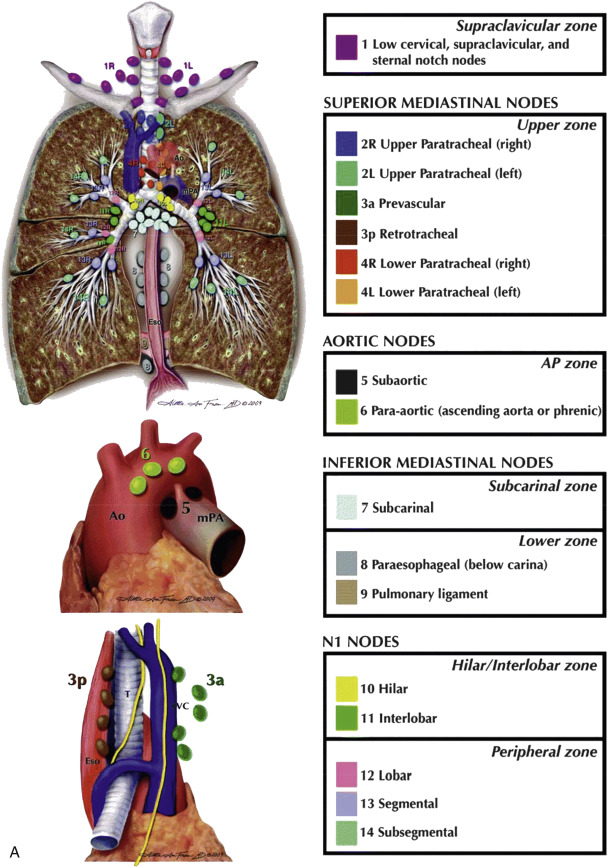

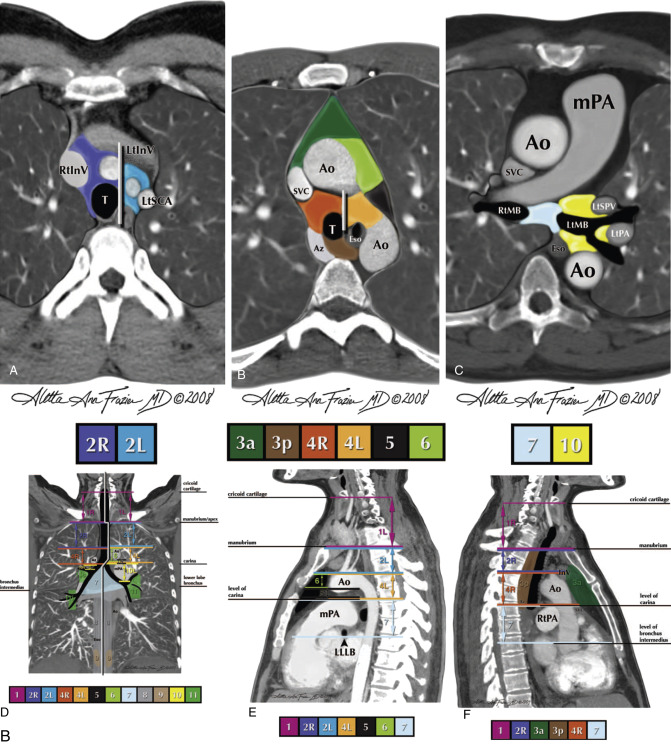

Lymph Node Stations

Several numerical systems have been proposed for identifying the specific locations of intrathoracic lymph nodes (i.e., lymph node stations ), primarily for the purpose of lung cancer staging. In 1997 the American Thoracic Society (ATS) published a classification of 14 lymph node stations, with precise anatomic and CT criteria, which has been in common usage since its description, for the localization of lymph node abnormalities in a variety of diseases.

In 2009 the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) introduced a simplified system for classifying lymph nodes, based on lung cancer survival statistics, for use in lung cancer staging ( Table 4.1 ). This system classifies mediastinal nodes into four groups or zones known as (1) the upper zone (paratracheal and prevascular nodes), (2) the aortopulmonary zone (aortopulmonary window nodes), (3) the subcarinal zone (subcarinal nodes), and (4) the lower zone (paraesophageal and inferior pulmonary ligament nodes). In addition, the IASLC system includes the supraclavicular zone (right and left supraclavicular lymph nodes), the hilar/interlobar zone (hilar lymph nodes), and the peripheral zone (lobar, segmental and subsegmental nodes). Table 4.1 provides a comparison of IASLC zones and ATS lymph node stations, and Fig. 4.6 shows a diagrammatic representation of ATS lymph node stations and comparable IASLC lymph node zones. Detailed knowledge of these lymph node stations and zones is not necessary in routine clinical practice.

CT Appearance of Lymph Nodes

Lymph nodes are generally visible as discrete opacities, round or elliptical in shape, of soft-tissue attenuation, surrounded by mediastinal fat, and distinguishable from vessels by their location. They often occur in clusters ( Fig. 4.7 ). In some locations, nodes that contact vessels may be difficult to identify without contrast medium infusion. Normal lymph nodes may show a fatty hilum ( Fig. 4.7 ).

Lymph Node Size

The short-axis or least diameter (i.e., the smallest node diameter seen in cross section) is generally used when one is measuring the size of a lymph node. Measuring the short-axis diameter is better than measuring the long-axis or greatest diameter because it more closely reflects the actual node diameter when nodes are obliquely oriented relative to the scan plane and shows less variation among healthy individuals.

Normal lymph nodes are commonly visible on CT. They differ in size, depending on their location. There are a few general rules:

- •

Subcarinal nodes can be large in healthy individuals.

- •

Pretracheal nodes are typically smaller than subcarinal nodes.

- •

Right paratracheal (pretracheal) nodes are usually larger than left-sided nodes.

- •

Upper mediastinum nodes are usually smaller than nodes nearer the carina.

- •

Internal mammary nodes, paracardiac nodes, and paravertebral nodes measure only a few millimeters.

Different values for the upper limits of normal short-axis node diameter have been found for different mediastinal node groups ( Table 4.2 ). However, except for the subcarinal regions, a short-axis node diameter of 1 cm or less is generally considered normal for clinical purposes. In the subcarinal region, 1.5 cm is usually considered to be the upper limit of normal.

| Node Group | Short-Axis Node Diameter a (mm) |

|---|---|

| Supra-aortic paratracheal | 7 |

| Subaortic paratracheal | 9 |

| Aortopulmonary window | 9 |

| Prevascular | 8 |

| Subcarinal | 12 |

| Paraesophageal | 8 |

Lymph Node Enlargement

Except in the subcarinal space, lymph nodes are considered to be enlarged if they have a short-axis diameter greater than 1 cm. In most cases, abnormal nodes are outlined by fat and are visible as discrete structures ( Fig. 4.3 ). However, in the presence of inflammation or neoplastic infiltration, abnormal nodes can be matted together, giving the appearance of a single large mass or resulting in infiltration and replacement of mediastinal fat by soft-tissue opacity.

The significance given to the presence of an enlarged lymph node must be tempered by knowledge of the patient’s clinical situation. For example, if the patient is known to have lung cancer, then an enlarged lymph node has a 70% likelihood of tumor involvement. However, the same node in a patient without lung cancer is much less likely to be of clinical significance. In the absence of a known disease, an enlarged node must be regarded as likely hyperplastic or reactive.

On the other hand, the larger a node is, the more likely it is to represent a significant abnormality. Mediastinal lymph nodes larger than 2 cm are often involved by tumor, although large lymph nodes may also be seen in patients with sarcoidosis or other granulomatous diseases.

Lymph Node Calcification

Lymph node calcification can be dense, homogeneous, focal, stippled, or eggshell (ring-like) in appearance. The abnormal nodes are often enlarged but can also be of normal size. Multiple calcified lymph nodes are often visible, usually in contiguity.

Lymph node calcification usually indicates prior granulomatous disease, including tuberculosis, histoplasmosis and other fungal infections, and sarcoidosis ( Fig. 4.8 ). The differential diagnosis also includes silicosis, coal workers’ pneumoconiosis, treated Hodgkin disease, metastatic neoplasm, typically mutinous adenocarcinoma, thyroid carcinoma, or metastatic osteogenic sarcoma. Eggshell calcification is most often seen in patients with silicosis or coal workers’ pneumoconiosis, sarcoidosis, and tuberculosis.

Low-Attenuation or Necrotic Lymph Nodes

Enlarged lymph nodes may appear to be low in attenuation ( Fig. 4.5 ), often with an enhancing rim if contrast medium has been injected. Typically, low-attenuation nodes reflect the presence of necrosis. They are commonly seen in patients with active tuberculosis, fungal infections, and neoplasms, such as metastatic carcinoma and lymphoma.

Lymph Node Enhancement

Normal lymph nodes may show some increase in attenuation after intravenous contrast medium infusion. Pathologic lymph nodes with an increased vascular supply may increase significantly in attenuation. The differential diagnosis of densely enhanced mediastinal nodes is limited and includes metastatic neoplasm (e.g., lung cancer, breast cancer, renal cell carcinoma, papillary thyroid carcinoma, sarcoma, and melanoma), Castleman disease ( Fig. 4.9 ), infections such as tuberculosis, and sometimes sarcoidosis.

Lung Cancer

Approximately 35% of patients in whom lung cancer has been diagnosed have mediastinal node metastases ( Fig. 4.10 ). Lung cancer most often involves the middle mediastinal node groups. Cancers of the left upper lobe typically metastasize to aortopulmonary window nodes, whereas tumors involving the lower lobes tend to metastasize to the subcarinal and right paratracheal groups. Tumors of the right upper lobe typically involve paratracheal nodes.

Lymph Node Metastases in Lung Cancer

In patients with lung cancer the likelihood that a mediastinal node is involved by tumor is directly proportional to its size. However, although enlarged nodes are most likely to be involved by tumor ( Fig. 4.10 ), they can be benign; similarly, although small nodes are usually normal, they can harbor metastases. Although a short-axis measurement of greater than 1 cm is used in clinical practice to identify abnormally enlarged nodes, it is important to realize that no node diameter clearly separates benign nodes from those involved by tumor.

With use of a short-axis node diameter of 1 cm as the upper limit of node size, CT will detect mediastinal lymph node enlargement in about 60% of patients with node metastases (CT sensitivity), whereas about 70% of patients with normal nodes will be classified as normal on CT (CT specificity). Although CT is not highly accurate in diagnosing node metastases, it is commonly used to guide subsequent procedures or treatment.

In contrast, if mediastinal lymph node enlargement is seen on CT, about 70% of patients will have node metastases; benign hyperplasia of mediastinal lymph nodes accounts for the other 30%. Patients with large mediastinal nodes may undergo node sampling at mediastinoscopy or by CT-guided needle biopsy before surgery.

Positron emission tomography (PET) is more accurate than CT in the assessment of mediastinal lymph node metastases in lung cancer and has assumed a significant role in preoperative staging. PET has a sensitivity of about 80% for diagnosis of mediastinal node metastases (vs. 60% for CT) and a specificity of about 90% (compared with 70% for CT). PET is often combined with CT (PET-CT) because of the poor anatomic detail provided by PET alone. In a patient with lung cancer, PET-CT is commonly done rather than a routine CT in staging.

Lung Cancer Staging

In patients with non–small cell lung carcinoma, the genetics, cell type, and histologic characteristics of the tumor affect prognosis, but the anatomic extent of the tumor (tumor stage) is usually most important in determining the therapeutic approach and the use of chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and/or surgery. Lung cancer is staged by a TNM system, based on consideration of (1) the size, location, and extent of the primary tumor (T); (2) the presence or absence of lymph node metastases (N); and (3) the presence or absence of distant metastases (M). Tumor stage (I, II, III, or IV, with subdivisions) is based on specific groupings of T, N, and M categories and subcategories. With this classification, excellent correlations are found between tumor stage and survival after treatment.

The eighth edition of the lung cancer TNM staging system (TNM-8) has recently been published and is based on analysis of more than 75,000 lung cancer patients; the staging system was last revised in 2009 (TNM-7). A somewhat condensed and edited version of the TNM-8 categories is provided in Tables 4.3 and 4.4 , and the reader is referred to Suggested Reading (Rami-Porta et al.) for a detailed review.

| T (primary tumor) | |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ: adenocarcinoma in situ or squamous cell carcinoma in situ |

| T1 | A tumor that is: |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| T2 | A tumor with any of the following features: |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| T3 | A tumor with any of the following features: |

| |

| |

| |

| T4 | A tumor with any of the following features: |

| |

| |

| |

| N (regional lymph nodes) | |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastases |

| N1 | Metastases to ipsilateral peribronchial and/or hilar and intrapulmonary nodes, including direct extension |

| N2 | Metastases to ipsilateral mediastinal nodes and/or subcarinal nodes |

| N3 | Metastases to contralateral hilar or mediastinal lymph nodes, or scalene or supraclavicular lymph nodes |

| M (distant metastases) | |

| M0 | Metastases absent |

| M1 | Metastases present |

| M1a intrathoracic metastases, with either | |

| |

| |

| M1b single extrathoracic metastasis; involvement of single distant lymph node a | |

| M1c multiple extrathoracic metastases in one or more organs a | |

| Stage | T | N | M |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

| IA1 | T1mi | N0 | M0 |

| T1a | N0 | M0 | |

| IA2 | T1b | N0 | M0 |

| IA3 | T1c | N0 | M0 |

| IB | T2a | N0 | M0 |

| IIA | T2b | N0 | M0 |

| IIB | T1a,b,c | N1 | M0 |

| T2a,b | N1 | M0 | |

| T3 | N0 | M0 | |

| IIIA | T1a,b,c | N2 | M0 |

| T2a,b | N2 | M0 | |

| T3 | N1 | M0 | |

| T4 | N0, N1 | M0 | |

| IIIB | T1a,b,c | N3 | M0 |

| T2a,b | N3 | M0 | |

| T3, T4 | N2 | M0 | |

| IIIC | T3, T4 | N3 | M0 |

| IVA | Any T | Any N | M1a,b |

| IVA | Any T | Any N | M1c |

No changes were made in lymph node categories in TNM-8, although it has been shown that the number of nodal zones or stations involved impacts prognosis. In TNM-8 (as in TNM-7) lung lymph node (N) designations are as follows:

- •

N0: absence of regional lymph node metastases;

- •

N1: metastasis to ipsilateral peribronchial and/or hilar or intrapulmonary lymph nodes;

- •

N2: metastasis to ipsilateral mediastinal and/or subcarinal lymph nodes;

- •

N3: metastasis to contralateral mediastinal or hilar nodes; or scalene or supraclavicular nodes on either side.

In routine practice a precise classification of tumor stage is not usually necessary. However, differentiation of potentially resectable stages (stage I to stage IIIa) and stages usually considered unresectable (stage IIIb to stage IV) is important ( Table 4.4 ). Keep in mind that the criteria for resectability are generally accepted, but are not absolute, and depend on several factors.

N0 and N1 nodes, in and of themselves, are considered resectable. N2 lymph nodes are considered potentially resectable (although this is not always the case). N3 nodes are considered unresectable ( Fig. 4.10 ). In the absence of metastases (M1a–M1c), the following rules apply:

- •

N0 or N1 nodes, depending on the primary tumor, may be part of stage I, II, or IIIa.

- •

N2 nodes, depending on the primary tumor, may be part of stage IIIa or IIIb.

- •

N3 nodes are associated with stage IIIc.

A number of changes regarding primary tumor descriptors and stage classification were made in TNM-8 ( Tables 4.3 and 4.4 ). However, a discussion of lung cancer staging in this chapter is limited to a review of lymph node metastases and mediastinal invasion. Other important findings in staging lung cancer are discussed in other chapters. These include hilar lymph node enlargement and hilar mass ( Chapter 5 ), primary tumor characteristics ( Chapter 6 ), and pleural and chest wall invasion ( Chapter 7 ).

Mediastinal Invasion by Lung Cancer

Lung cancer can invade the mediastinum by direct extension, resulting in a mediastinal mass contiguous with the primary tumor. In TNM-8, invasions of the parietal pleura, parietal pericardium, phrenic nerve, or chest wall are termed T3 , and in the absence of mediastinal lymph node metastases are classified as stage IIB or IIIA ( Table 4.4 ). Invasions of the diaphragm, mediastinum, heart, great vessels, trachea, carina, esophagus, recurrent laryngeal nerve, or vertebral body are termed T4 , and in the absence of mediastinal lymph node metastases are classified as stage IIIA. Stage IIIA tumors are potentially resectable.

How accurate is CT in predicting mediastinal invasion? An obvious finding is that a lung mass not contacting the mediastinum is not invasive, and this is an important use of CT.

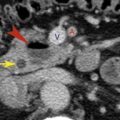

CT findings of mediastinal invasion ( Fig. 4.11 ) include:

- •

replacement of mediastinal fat by tumor (i.e., soft tissue);

- •

compression, displacement, or obstruction of mediastinal structures;

- •

extensive contact of tumor with a mediastinal structure, such as the aorta or trachea (e.g., one-quarter or more of its circumference);

- •

obliteration of the fat planes normally seen adjacent to mediastinal structures;

- •

pericardial thickening associated with a mass.