SONOGRAM ABBREVIATIONS

Ab Abscess

Ao Aorta

Bl Bladder

Ca Celiac artery

GBl Gallbladder

Ia Iliac artery

Ip Iliopsoas muscle

IVC Inferior vena cava

K Kidney

L Liver

N Nodes

P Pancreas

Ps Psoas muscle

QL Quadratus lumborum muscle

RA Rectus abdominis muscle

SMA Superior mesenteric artery

Sp Spleen

KEY WORDS

Adenopathy. Abnormally enlarged lymph nodes.

Aneurysm. Dilatation of an artery, usually the abdominal aorta. There are several types of aneurysms:

True Aneurysm. Enlargement of all three layers of the aorta.

False Aneurysm. Leaking of blood through all three layers of the vessel into surrounding tissues that contain it.

Dissecting Aneurysm. An aneurysm that occurs when the intima layer of the vessel wall separates from the media layer, secondary to bleeding.

Fusiform Aneurysm. A spindle-shaped dilation of an artery.

Saccular Aneurysm. A sac-like dilatation of an artery.

Ascites. Abnormal accumulation of fluid in the abdomen or pelvis.

Exudate. Free fluid that seeps out from blood vessels. Characterized by a high protein and cellular content.

Transudate. Free fluid that passes through membranes, causing protein and cellular content to be filtered out.

Abdominal Aortic Bifurcation. The abdominal aorta divides into the right and left common iliac arteries at approximately the level of the umbilicus.

Crohn’s Disease. Chronic inflammatory bowel disease that causes ulcers along the inner surface of the bowel. Infection and bowel obstruction are common symptoms.

Haustra. Normal sacculations of the colon’s wall.

Hernia. Protrusion of bowel, fat and/or membranes through an abnormal opening. Hernias are classified according to location. (See Chapter 13.)

Intussusception. Telescoping of a portion of the intestine into an adjacent portion. Most common in children (see Chapter 35).

Ischemic Colitis. Inflammation of the colon resulting in a decreased blood supply. The bowel wall is thickened and does not demonstrate peristalsis.

Lymphoma. Malignancy of the lymph system.

Mechanical Obstruction. Obstruction of the bowel secondary to an extrinsic process, resulting in dilated fluid-filled loops.

Mesenteric Sheath. Membranous fold that attaches the bowel to the dorsal (back or posterior) body wall.

Paracolic Gutter. Area lateral to the ascending and descending colon where fluid may accumulate.

Paralytic Ileus. Paralysis of the intestine, usually occurring secondary to surgery, injury, certain drugs, or illness.

Peristalsis. Rhythmic contraction of the bowel used to propel contents through it. Visible with ultrasound.

Psoas Muscles. Paired muscles that lie lateral to the spine and posterior to the kidneys.

Rectus Abdominus Muscles. Paired, anterior, midline muscles that extend the length of the abdomen.

The Clinical Problem

Midabdominal masses can either originate in the midabdomen or extend from an extrinsic location. Masses that originate in the midabdominal region typically arise from the abdominal aorta, bowel, lymph nodes, or the abdominal wall. Most midabdominal masses can be visualized by ultrasound; however, air within the bowel may interfere in some cases.

AORTIC ANEURYSM

Ultrasound is a useful method for evaluating the abdominal aorta (Fig. 14-1). Information regarding size and location of the aneurysm can aid the surgeon in providing appropriate treatment. Descriptive terms such as saccular or fusiform may also be helpful (Fig. 14-2). In the case of large body habitus, other imaging modalities such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging may be necessary.

The abdominal aorta is considered aneurysmal if the anteroposterior diameter measures greater than 3 cm. Surgery is indicated, however, when the diameter is greater than ~5.5 cm. Evidence of significant expansion between sequential sonograms may indicate the need for surgical intervention.

An aneurysm that has ruptured, forming a false aneurysm, is an acute emergency.

LYMPH NODES

Enlarged lymph nodes may be visualized around the aorta and its branches. Adenopathy usually occurs due to an inflammatory or neoplastic process. Detection of nodal enlargement in the midabdomen should prompt an evaluation for the extent of lymphomatous spread. CT is typically the imaging modality of choice.

BOWEL MASSES

The clinician may palpate large masses arising from the bowel. Sonography is usually not the modality of choice when evaluating for bowel masses due to interference from overlying bowel gas.

Some masses may be incidentally found by ultrasound. Secondary signs of a mass, including thickened bowel wall or dilated fluid-filled loops of bowel due to an obstruction, may be seen by ultrasound.

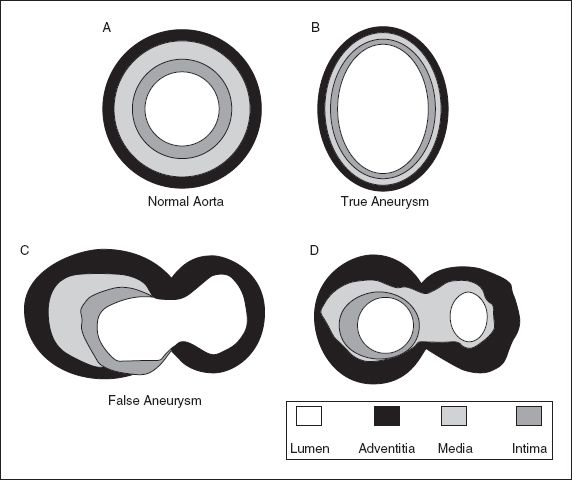

Figure 14-1. ![]() A. Normal aorta showing the three components of the wall—the intima (gray), media (hatched), and adventitia (black). B. True aneurysm. Diffuse swelling of the three layers. C. False aneurysm. Blood is released through all three layers into surrounding tissues. D. Dissection. There is a defect in the intima, with blood between the intima and media. (Adapted and reprinted with permission from Downey D. The retroperitoneum and the great vessels. In Rumack CM, Wilson SR, Charboneau JW, eds. Diagnostic Ultrasound, 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998:453–486.)

A. Normal aorta showing the three components of the wall—the intima (gray), media (hatched), and adventitia (black). B. True aneurysm. Diffuse swelling of the three layers. C. False aneurysm. Blood is released through all three layers into surrounding tissues. D. Dissection. There is a defect in the intima, with blood between the intima and media. (Adapted and reprinted with permission from Downey D. The retroperitoneum and the great vessels. In Rumack CM, Wilson SR, Charboneau JW, eds. Diagnostic Ultrasound, 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1998:453–486.)

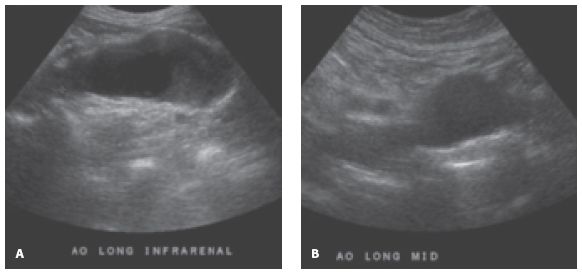

Figure 14-2. ![]() (A) A fusiform aneurysm that has a gradual change in diameter from superior (left caliper) to inferior (right caliper), whereas (B) a saccular aneurysm changes abruptly from normal to abnormal.

(A) A fusiform aneurysm that has a gradual change in diameter from superior (left caliper) to inferior (right caliper), whereas (B) a saccular aneurysm changes abruptly from normal to abnormal.

BOWEL OBSTRUCTION

Another cause of overall abdominal distention is intestinal obstruction or paralytic ileus. With these conditions, the abdomen can be extremely distended. Dilated bowel usually contains a mixture of air and fluid; therefore, an ultrasound exam may not provide an adequate evaluation. If the bowel is entirely fluid-filled and if air is not present, the sonogram can help by showing that the bowel is dilated. This finding may not be appreciated on a plain radiograph. Sonography can also be helpful if the obstruction is localized to a small segment of bowel.

During real-time ultrasound, a paralytic ileus can be distinguished from mechanical obstruction. With an ileus, there will not be peristalsis within the dilated bowel, whereas with early mechanical obstruction, the bowel will show evidence of marked peristalsis. These two conditions are treated differently: high-grade mechanical obstruction is an indication for surgery, whereas paralytic ileus is treated conservatively.

ASCITES

If the entire abdomen appears enlarged, the clinical question of ascites is raised—this is assessed relatively easily by ultrasound. Discovery of ascites is important because aspiration of the ascitic fluid can assist in patient management. Causes of ascites include congestive heart failure, liver disease, nephrotic syndrome, infection, and malignancy. Blood may also appear as simple fluid within the abdomen. This finding may be due to a recent ruptured aneurysm or trauma.

Anatomy

For information regarding anatomy, see Chapter 6, Sonographic Abdominal Anatomy.

AORTA

All vessels, including the aorta have three wall layers: the adventitia, media, and intima (Fig. 14-1).

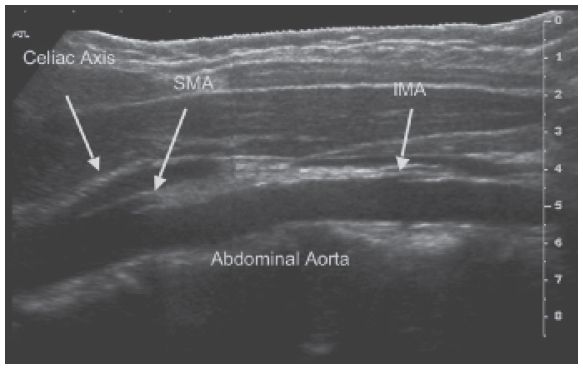

Figure 14-3. ![]() Longitudinal scan of a normal aorta and its branches.

Longitudinal scan of a normal aorta and its branches.

In the optimal patient, the aorta can be traced as far as the level of the bifurcation into the right and left common iliac arteries. The celiac axis, SMA, renal arteries, and inferior mesenteric artery arise from the aorta. Although sometimes obscured by overlying bowel gas, most branches can usually be visualized by ultrasound (Fig. 14-3).

The aorta lies midline directly anterior to the spine and to the left of the inferior vena cava (IVC).

MESENTERIC SHEATH

The mesenteric sheath (mesentery, mesenteric root) is a fibrous membrane that attaches the small and large bowel to the abdominal wall. The SMA and the superior mesenteric vein are contained within it. It is not visible by ultrasound unless it is surrounded by enlarged nodes.

BOWEL

Bowel is not well evaluated by ultrasound due to overlying bowel gas. When visualized, however, cross-sectional views through normal empty bowel show an echogenic center surrounded by a thin, echo-free wall. Bowel that is dilated, filled with fluid, or has a thickened wall is much easier to appreciate with ultrasound.

PSOAS MUSCLES

The psoas muscles can be seen on either side of the spine, posterior to the kidneys. The psoas muscles join with the iliacus muscles to form the iliopsoas muscles, which coat the anterior aspect of the iliac crest, just above the true pelvis.

RECTUS SHEATH MUSCLE

The two segments of the rectus muscle lie on either side of the midline in the anterior abdominal wall. They are seen well in the upper abdomen but are not readily visualized below the umbilicus (Fig. 14-4).

ABDOMINAL WALL

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree