Chapter Outline

Portal Hypertensive Gastropathy

Adult Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis

Gastric Dilation Without Gastric Outlet Obstruction

Widening of the Duodenal Sweep

Pancreatic Diseases Affecting the Stomach and Duodenum

Gastroduodenal and Duodenojejunal Intussusceptions

Gastric and Duodenal Perforation

Varices

Gastric Varices

Pathophysiology

Portal Hypertension.

The gastric fundus contains a venous plexus that is normally drained by numerous short gastric veins anastomosing distally with the splenic vein and proximally with branches of the coronary vein as well as venous channels surrounding the distal esophagus. Blood in the short gastric veins normally empties via the splenic vein into the portal venous system. In patients with portal hypertension, however, increased pressure in the portal and splenic veins leads to reversal of blood flow through the short gastric veins into the fundal venous plexus, producing fundal varices. As a result, gastric varices develop in 20% of patients with portal hypertension. Because elevated portal pressure also causes reversal of flow through the coronary vein (producing uphill esophageal varices), some patients with portal hypertension have combined gastric and esophageal varices. However, others with portal hypertension have isolated gastric varices, and an even greater number have isolated esophageal varices (see Chapter 25 ).

One explanation for the frequent failure to visualize gastric varices in patients with portal hypertension is that the venous channels in the gastric fundus have thicker, better connective tissue support than the thin-walled, loosely supported veins in the distal esophagus. As a result, varices may be more likely to form in the esophagus than in the stomach, despite comparable elevations in pressure. Even when gastric varices are present, they may be obscured on barium studies or endoscopy by overlying gastric rugae.

Splenic Vein Obstruction.

In patients with splenic vein obstruction, increased pressure in the splenic vein beyond the obstruction leads to reversal of flow through the short gastric veins to the fundal plexus of veins, producing gastric varices. Because these patients have normal portal pressure, however, venous blood from the dilated fundal plexus can enter the portal venous system via the coronary vein without producing uphill esophageal varices. As a result, splenic vein obstruction is characterized by isolated varices in the gastric fundus without associated varices in the esophagus.

Splenic vein obstruction may result from intrinsic thrombosis or, more commonly, from extrinsic compression of the splenic vein by a variety of benign or malignant conditions, including pancreatitis, pancreatic pseudocysts, pancreatic carcinoma, metastatic disease, lymphoma, and retroperitoneal fibrosis or bleeding. Intrinsic thrombosis of the splenic vein may be idiopathic or may result from polycythemia or other myeloproliferative disorders.

Clinical Findings

Gastric varices are important because of the risk of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, which can range from low-grade, intermittent bleeding to massive hematemesis. Gastric varices are less likely to bleed than esophageal varices because of their subserosal location and the greater thickness of overlying gastric tissue. When gastric variceal bleeding occurs, however, it tends to be more severe than esophageal variceal bleeding and is associated with a higher mortality rate. When gastric varices are associated with esophageal varices, affected individuals usually have the stigmata of portal hypertension. In contrast, patients with isolated gastric varices caused by splenic vein obstruction may present with abdominal pain and weight loss from underlying pancreatitis or pancreatic carcinoma. Splenomegaly is also a frequent finding in splenic vein obstruction, but a normal-sized spleen does not exclude this condition.

Radiographic Findings

Abdominal Radiographs.

Large gastric varices may occasionally be recognized on chest or abdominal radiographs as one or more lobulated soft tissue densities in the gas-filled fundus. Depending on the cause of the varices (portal hypertension or splenic vein obstruction), abdominal radiographs may also reveal splenomegaly, ascites, or pancreatic calcification. When gastric varices are suspected on the basis of abdominal radiographs other imaging tests such as barium studies, endoscopy, or computed tomography (CT) should be performed for a more definitive diagnosis.

Barium Studies.

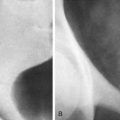

Conventional single-contrast barium studies are thought to be unreliable for detecting gastric varices. Double-contrast technique has therefore been advocated to improve visualization of these structures. Gastric varices may appear as thickened, tortuous folds or as round submucosal filling defects in the gastric fundus, resembling the appearance of a bunch of grapes ( Fig. 34-1 ). Less frequently, a conglomerate mass of fundal varices, also known as tumorous gastric varices, may be manifested by a large polypoid mass that can be mistaken on barium studies for a polypoid carcinoma or even a malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) ( Figs. 34-2 and 34-3 ). Tumorous varices have characteristic features, however, appearing in profile as smooth submucosal masses with an undulating contour and discrete borders on the posteromedial wall of the gastric fundus (see Figs. 34-2 and 34-3 ) and en face as thickened, tortuous folds that fade peripherally into the adjacent mucosa. These radiographic features should allow differentiation from polypoid gastric neoplasms in most cases. Rarely, dilated gastroepiploic veins may be manifested by varices in the antrum or body of the stomach ( Fig. 34-4 ).

When gastric varices are detected on barium studies, it is important to determine whether uphill esophageal varices are also present in these patients. The presence of combined esophageal and gastric varices almost always indicates portal hypertension as the underlying cause. In contrast, isolated gastric varices should raise the possibility of splenic vein obstruction with a patent portal vein (see Fig. 34-3 ). Nevertheless, portal hypertension is much more common than splenic vein obstruction, so most patients with gastric varices, even in the absence of esophageal varices, are found to have portal hypertension as the underlying cause (see Fig. 34-2 ). If necessary, CT or angiography may be performed to document the presence of varices and elucidate their pathophysiology.

Computed Tomography.

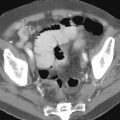

Gastric varices are usually recognized on CT as enhancing, well-defined, round or tubular densities on the posterior or posteromedial wall of the gastric fundus ( Fig. 34-5 ). CT is more sensitive than conventional radiologic examinations in detecting these lesions because barium studies can only demonstrate varices that protrude into the lumen, whereas CT can delineate deeper intramural and perigastric varices. CT may also reveal cirrhotic liver disease, splenomegaly, or ascites in patients with portal hypertension (see Fig. 34-5 ) and splenomegaly or pancreatic disease in patients with splenic vein obstruction.

Angiography.

Angiography may be performed to confirm the presence of gastric varices and determine the nature of the underlying venous abnormality. With portal hypertension, reversal of flow through the coronary and short gastric veins leads to the formation of esophageal and gastric varices, with absent visualization of the portal and splenic veins. With splenic vein obstruction, however, delayed images reveal normal filling of a patent portal vein without evidence of esophageal varices, as blood is diverted from the fundal plexus of veins via the coronary vein to the portal venous system, bypassing the obstructed splenic vein ( Fig. 34-6 ). Thus, portal hypertension can usually be differentiated from splenic vein obstruction by angiography, so appropriate therapy can be instituted in these patients.

Differential Diagnosis

When gastric varices are manifested on barium studies by thickened, nodular folds in the fundus, the differential diagnosis includes Helicobacter pylori gastritis, Ménétrier’s disease, Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, pancreatitis, and lymphoma. However, gastric varices tend to be more tortuous or lobulated than these other conditions and are often associated with esophageal varices. Occasionally, a conglomerate mass of fundal varices may resemble a polypoid carcinoma or even a malignant GIST (see Figs. 34-2 and 34-3 ). However, the vascular origin of these lesions is suggested by their smooth undulating contour and typical location on the posteromedial wall of the gastric fundus. CT or angiography may be required for a definitive diagnosis. It is particularly important to differentiate gastric varices from other lesions before performing endoscopic biopsy or surgery because inadvertent perforation of a varix may lead to catastrophic GI bleeding.

Treatment

Emergent treatment for bleeding gastric varices is rarely necessary. When major bleeding does occur in patients with splenic vein obstruction, the patients are almost always cured by simple splenectomy because portal venous pressure is normal in these individuals. In contrast, some form of portosystemic shunt may be required for gastric varices caused by portal hypertension, as splenectomy alone has no effect on portal venous pressure in these patients. Thus, the choice of treatment for gastric varices depends on the underlying cause.

Duodenal Varices

Duodenal varices typically appear on barium studies as thickened, serpiginous folds in the proximal duodenum ( Fig. 34-7 ). They are almost always associated with esophageal varices and may be complicated by GI bleeding. Occasionally, an isolated duodenal varix can present as a solitary filling defect.

Portal Hypertensive Gastropathy

Portal hypertensive gastropathy is a distinct pathologic entity caused by chronic portal hypertension. Chronic venous congestion in the stomach results in mucosal hyperemia, capillary ectasia, and increased numbers of submucosal arteriovenous communications with dilated arterioles, capillaries, and veins in the gastric wall. For reasons that are unclear, portal hypertensive gastropathy occurs more frequently in patients with cirrhosis than in other patients with portal hypertension. This condition is a cause of acute and chronic upper GI bleeding, even in the absence of esophageal or gastric varices. It has been estimated that nonvariceal bleeding from portal hypertensive gastropathy is responsible for up to 30% of all cases of upper GI bleeding in patients with portal hypertension.

Radiographic Findings

Portal hypertensive gastropathy predominantly involves the gastric fundus and is manifested on barium studies by thickened, nodular folds with undulating contours and indistinct borders ( Fig. 34-8 ). Although the pathophysiologic basis for this fold thickening is uncertain, it could result from a combination of mucosal hyperemia and dilated submucosal vessels. Gastric varices may also appear as thickened folds on barium studies, but the folds tend to have a more serpentine configuration and are often associated with discrete submucosal masses (see Fig. 34-1 ). The differential diagnosis also includes various forms of gastritis (especially H. pylori gastritis), lymphoma, and, rarely, Ménétrier’s disease.

Diverticula

Gastric Diverticula

Gastric diverticula almost always arise on a discrete neck from the posterior wall of the fundus and usually cause no symptoms. Barium studies best show a gastric fundal diverticulum in profile on lateral views of the fundus, but a collection of barium pooling within the diverticulum can occasionally mimic an area of ulceration ( Fig. 34-9 ).

Intramural or partial gastric diverticulum is a rare anomaly of no clinical importance that is characterized by focal invagination of the mucosa into the muscular layer of the gastric wall. These structures are almost always located on the greater curvature of the distal antrum. The diverticulum may be manifested on barium studies by a tiny collection of barium extending outside the contour of the adjacent gastric wall ( Fig. 34-10 ). Although these structures can be mistaken for ulcers or even ectopic pancreatic rests on the greater curvature, they tend to have a changeable configuration at fluoroscopy, whereas true ulcers have a fixed appearance.

Duodenal Diverticula

True Diverticula

Duodenal diverticula are detected as incidental findings on upper GI barium studies in up to 15% of patients. The diverticula are acquired lesions, consisting of a sac of mucosal and submucosal layers herniating through a muscular defect. These diverticula often fill and empty by gravity as a result of pressure generated by duodenal peristalsis. Most duodenal diverticula are located on the medial border of the descending duodenum in the periampullary region ( Fig. 34-11 ), but they not infrequently are found in the third or fourth portion of the duodenum and can occasionally be located on the lateral border of the descending duodenum ( Fig. 34-12 ).

Duodenal diverticula typically appear on barium studies as smooth, round or ovoid outpouchings arising on a discrete neck from the medial border of the descending duodenum (see Fig. 34-11 ). They are often multiple and may change in size and shape at fluoroscopy. The lack of inflammatory reaction (spasm or edema) allows a duodenal diverticulum to be differentiated from a postbulbar ulcer. Bizarre multilobulated or giant diverticula are occasionally seen. Filling defects representing inspissated food particles or blood clots can sometimes be found within the diverticulum ( Fig. 34-13 ).

When duodenal diverticula contain gas or a combination of fluid and gas, they are readily visible on CT. However, a diverticulum that is predominantly fluid-filled can occasionally mimic the CT findings of a cystic neoplasm in the head of the pancreas ( Fig. 34-14A ). The correct diagnosis can still be established, however, if intradiverticular gas is identified ( Fig. 34-14B ).

More than 90% of patients with duodenal diverticula are asymptomatic. Occasionally, however, these patients may develop serious complications such as duodenal diverticulitis, upper GI bleeding, gastric outlet obstruction, and pancreaticobiliary disease. Because duodenal diverticula are retroperitoneal structures, duodenal diverticulitis and perforation can occur without clinical signs of peritonitis or radiographic signs of free intraperitoneal air. Instead, abdominal radiographs may reveal localized retroperitoneal gas adjacent to the duodenum and upper pole of the right kidney. Studies with barium or water-soluble contrast agents may demonstrate localized extravasation of contrast material from the perforated diverticulum into a contained extraluminal collection or a deformed diverticulum secondary to a previous perforation that subsequently sealed off. CT is particularly helpful for showing a contained perforation or inflammatory changes involving adjacent structures.

Rarely, duodenal diverticula may cause massive upper GI bleeding. In such cases, scanning with 99m Tc–labeled red blood cells or angiography may be required to localize the site of bleeding. Duodenal diverticula have also been described as a rare cause of duodenal or even biliary obstruction. Anomalous insertion of the common bile duct and pancreatic duct into a duodenal diverticulum can be demonstrated in about 3% of carefully performed T-tube cholangiograms. This anatomic variation can impair drainage of bile into the duodenum, predisposing these patients to biliary obstruction, bile duct stones, and pancreatitis.

Pseudodiverticula

Pseudodiverticula are exaggerated outpouchings or sacculations of the inferior and superior recesses of the duodenal bulb related to acute or chronic duodenal ulcer disease ( Fig. 34-15 ). The sacculations may be caused by edema and spasm associated with an active ulcer or by asymmetric fibrosis and retraction associated with scarring from a healed ulcer. However, the degree of deformity is not directly related to the size of the ulcer because some small duodenal ulcers may produce large sacculations, whereas other large ulcers may have little or no effect on the contour of the bulb.

Intraluminal Diverticula

An intraluminal duodenal diverticulum is a sac of duodenal mucosa originating from the second portion of the duodenum near the papilla of Vater. The term intraluminal diverticulum is actually a misnomer because this structure is not a diverticulum, but begins as a congenital duodenal web or diaphragm containing a small central aperture; the web gradually elongates over time because of forward pressure by food and duodenal peristalsis. As a result, the diverticulum usually extends antegrade into the distal descending duodenum or, occasionally, the third or fourth portion of the duodenum. When filled with barium, this structure has a characteristic radiographic appearance on barium studies and abdominal CT, with a finger-like intraluminal sac separated from barium in the adjacent lumen by a thin radiolucent stripe representing the elongated web, or “wall,” of the diverticulum ( Fig. 34-16 ). Because of the resemblance to a wind sock at small airports, this structure has also been called a “wind sock” diverticulum.

Both an intraluminal duodenal diverticulum and congenital duodenal diaphragm can be associated with a variety of other anomalies, including annular pancreas, midgut volvulus, situs inversus, choledochocele, congenital heart disease, Down syndrome, imperforate anus, Hirschsprung’s disease, omphalocele, and exstrophy of the bladder.

Patients with an intraluminal duodenal diverticulum may present with nausea and vomiting from associated duodenal obstruction. The usual treatment is surgery, but some patients may benefit from endoscopic disruption of the underlying duodenal web responsible for their symptoms, avoiding the need for surgery.

Webs and Diaphragms

Antral Webs and Diaphragms

Antral webs and diaphragms are thin membranous septa that are usually located within 3 cm of the pyloric canal and are oriented perpendicular to the long axis of the stomach. Clinical symptoms of partial gastric outlet obstruction correlate with the size of the central aperture of the web or diaphragm; obstructive symptoms do not occur if the diameter of the aperture is greater than 1 cm. Even with minute central orifices as small as 2 mm, these diaphragms may not cause obstructive symptoms until adult life.

Nonobstructive antral webs and diaphragms appear on barium studies as persistent, sharply defined, 2- to 3-cm-wide, band like defects in the barium column occurring at right angles to the gastric wall ( Fig. 34-17 ). A similar appearance may be produced by a prominent transverse antral fold, but transverse folds do not generally extend across the gastric lumen, and they are not perfectly straight. Antral webs and diaphragms are best visualized when the antrum is adequately distended proximal and distal to this structure. Occasionally, the antrum distal to the web can be mistaken radiographically for the duodenal bulb ( Fig. 34-18 ) or, less frequently, for a gastric diverticulum or ulcer. With severe obstruction, gastric emptying is greatly delayed, and barium can be seen to pass in a thin stream (jet phenomenon) through the central orifice of the web.

Duodenal Webs and Diaphragms

Duodenal webs and diaphragms are weblike projections in the duodenal lumen that cause varying degrees of obstruction. Most reported cases have involved the second portion of the duodenum near the ampulla of Vater. A congenital duodenal web usually appears on barium studies as a thin radiolucent line extending across the lumen, often associated with proximal duodenal dilation ( Fig. 34-19 ). Because the obstruction is incomplete, small amounts of gas may be present in more distal portions of the bowel. Rarely, a web may balloon distally, forming an intraluminal duodenal diverticulum (see earlier, “ Intraluminal Diverticula ”). Although the vast majority of duodenal webs and diaphragms are thought to be congenital, acquired duodenal diaphragms similar to those in the small bowel have been described as a rare complication of long-term use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Adult Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis

The histologic, anatomic, and radiographic abnormalities in adult hypertrophic pyloric stenosis are indistinguishable from those in the infantile form. The disease in adults may represent a milder form of the same entity observed in infants and children. Most cases of adult hypertrophic pyloric stenosis go unrecognized because these individuals are asymptomatic. However, some patients complain of nausea and vomiting, epigastric pain, weight loss, or anorexia, and approximately 50% of patients with adult hypertrophic pyloric stenosis have associated gastric ulcers. These ulcers probably develop as a result of delayed gastric emptying with increased gastrin production and hyperacidity. In contrast to children, adults with this condition rarely develop high-grade gastric outlet obstruction.

Adult hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is typically manifested on barium studies by elongation and narrowing of the pyloric canal as a result of a hypertrophied pyloric muscle ( Fig. 34-20 ). The pylorus can be as long as 2 to 4 cm in these patients (the normal length is <1 cm in adults). The proximal end of the narrowed pylorus merges gradually with the adjacent antrum, producing a smooth, tapered juncture without the shoulders expected for a malignant neoplasm. In contrast, the distal end of the hypertrophied pyloric muscle may bulge into the duodenum, producing a distinctive concave indentation on the base of the duodenal bulb (see Fig. 34-20 ). Some patients may have findings of gastric outlet obstruction.

Gastric Outlet Obstruction

Peptic ulcer disease is the most common cause of gastric outlet obstruction in adults, accounting for about two thirds of cases ( Fig. 34-21 ). The ulcers are usually located in the duodenal bulb, but may also be located in the pyloric channel or gastric antrum or, rarely, in the gastric body. Narrowing of the lumen in peptic ulcer disease can result from acute inflammation, edema and spasm, muscular hypertrophy, or fibrosis and scarring. In many cases, more than one of these factors contributes to the development of gastric outlet obstruction. Most patients with peptic ulcer disease causing pyloric obstruction have a long-standing history of ulcer symptoms. A gastric carcinoma should therefore be suspected when gastric outlet obstruction develops in previously asymptomatic patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree