Miscellaneous Lesions

Several benign and malignant lesions that did not fit into the classification included in the previous chapters are discussed here. Giant cell tumor, a locally aggressive neoplasm, occurs almost exclusively after skeletal maturity, when the growth plates are obliterated. Less than 5% of these lesions are malignant, although no clear imaging criteria are established to render such diagnosis. Simple bone cyst, also known as unicameral bone cyst, is a tumor-like lesion of unknown cause, attributed to a local disturbance of bone growth. Although its pathogenesis is still debatable, the lesion appears to be reactive or developmental rather than to represent a true neoplasm. Aneurysmal bone cyst may arise de novo in bone, or it may be associated with various benign (e.g., giant cell tumor, osteoblastoma, chondroblastoma, chondromyxoid fibroma, fibrous dysplasia) or malignant (e.g., osteosarcoma, fibrosarcoma, chondrosarcoma) lesions. Giant cell reparative granuloma, also known as a solid variant of aneurysmal bone cyst, is a lesion very similar to ABC taking in consideration its morphology and biologic behavior. Intraosseous lipoma is a rare lesion; in fact, many so-called intraosseous lipomas on closer examination turned out to be merely the simple hyperplasia of normal fatty bone marrow. Adamantinoma of long bones is a malignant tumor characterized by the formation of epithelial cells surrounded by a spindle cell fibrous tissue. A close relationship of this tumor to osteofibrous dysplasia and fibrous dysplasia has been suggested by some investigators. Moreover, some pathologists, on the basis of clinical course and of molecular and immunohistochemical analysis, suggested that osteofibrous dysplasia may be a precursor lesion of adamantinoma. Chordoma is a tumor that arises from developmental embryonic remnants of the notochord, with predilection to the spinal axis. Primary leiomyosarcoma of bone is a very rare bone malignancy composed of spindle cells exhibiting smooth muscle differentiation. Intraosseous liposarcoma is an extraordinary rare tumor with only handful of cases described in the literature.

A. BENIGN LESIONS

Giant Cell Tumor (GCT)

Definition:

Benign but locally aggressive tumor composed of proliferating ovoid mononuclear stroma cells interspersed with evenly distributed osteoclast-like multinucleated giant cells.

Epidemiology:

Represents about 5% of all primary bone tumors and 20% of benign primary bone tumors and is the sixth most common primary osseous neoplasm.

Occurs almost invariably after skeletal maturity.

The peak incidence is between ages 20 and 45, with mean age of 32.

Female-to-male ratio of 2:1.

Sites of Involvement:

Characteristically affects the articular ends of bone.

Long bones are affected in 60% of cases.

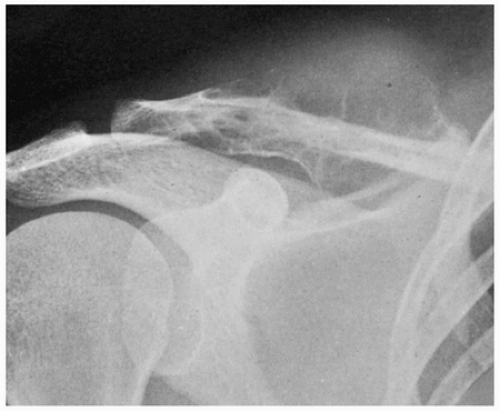

Preferential sites include the distal femur, proximal tibia, distal radius, proximal humerus, and sacrum.

Less than 5% affects short tubular bones of the hands and feet.

Very uncommonly the tumor is multifocal (usually associated with Paget disease).

Clinical Findings:

Pain of increasing intensity associated with local swelling and tenderness in the affected areas.

Limitation of motion in the adjacent joints.

Pathologic fractures occur in 5% to 10% of patients.

Less than 1% may undergo malignant transformation (mostly in older patients).

Tumor may extend to soft tissue or metastasize to the lung (intravascular invasion).

May arise in association with Goltz syndrome (focal dermal hypoplasia).

Imaging:

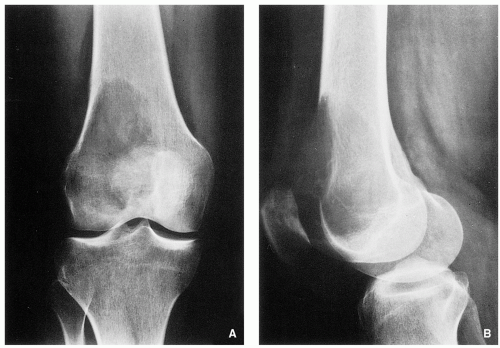

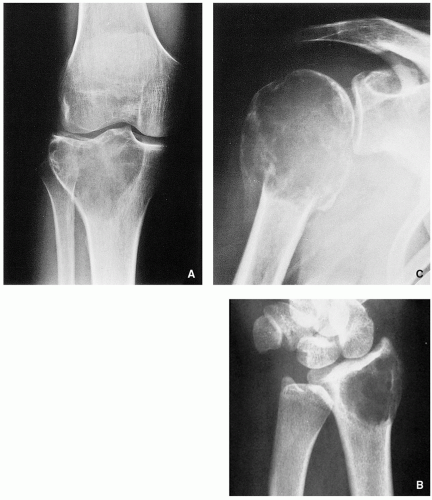

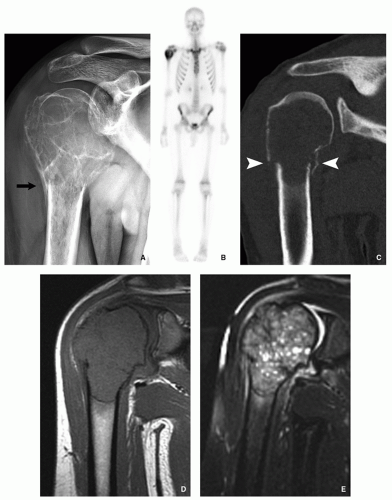

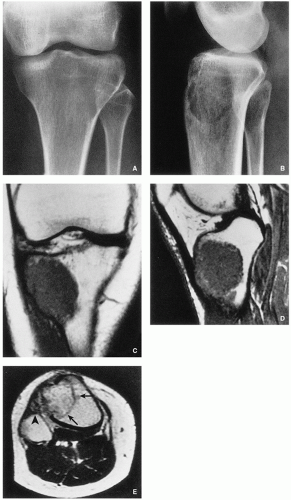

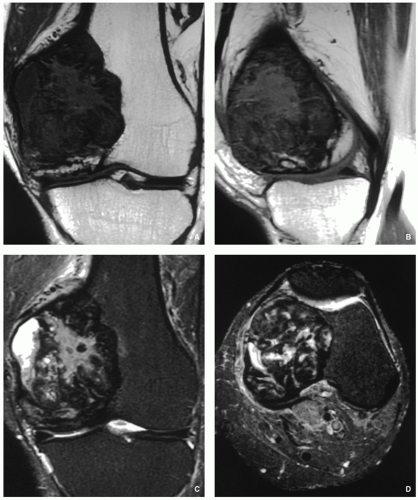

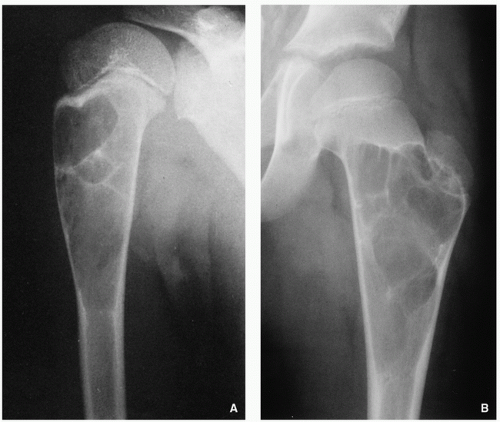

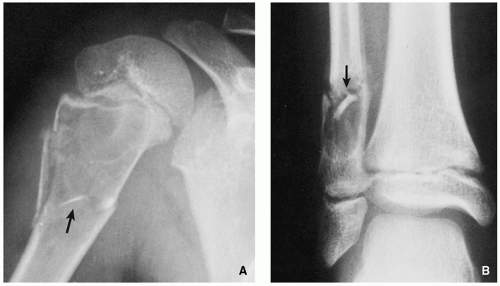

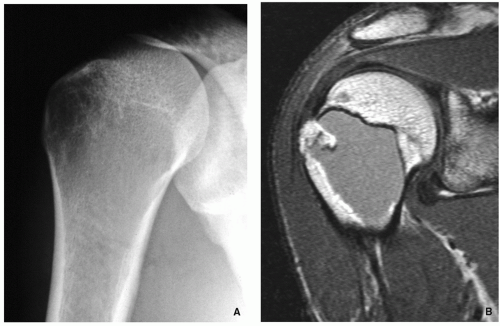

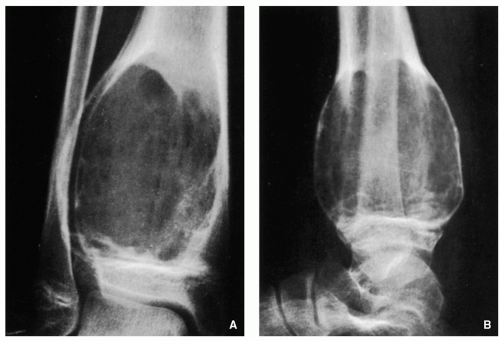

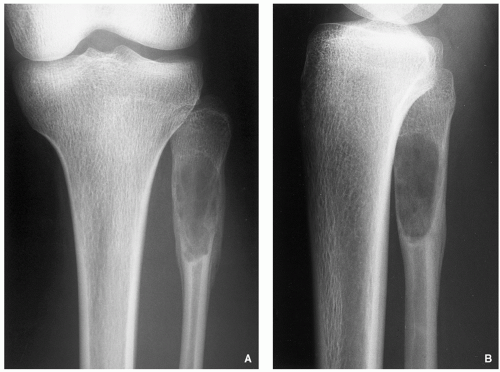

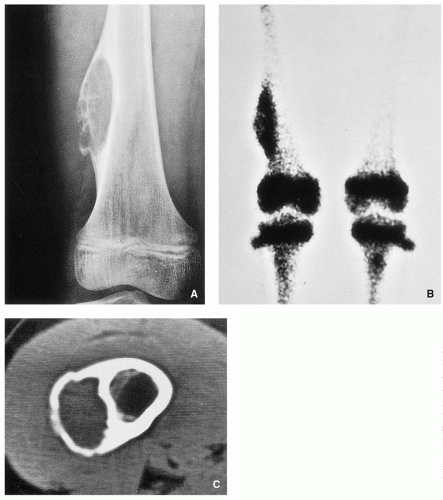

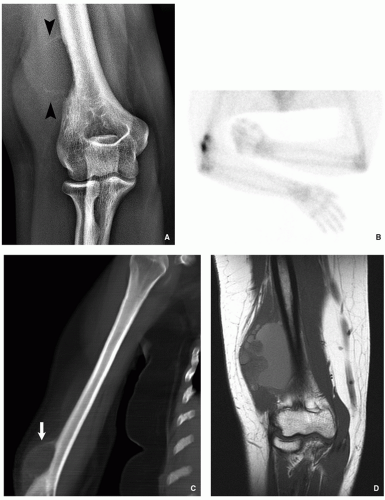

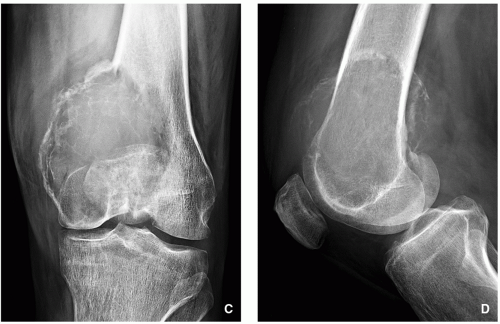

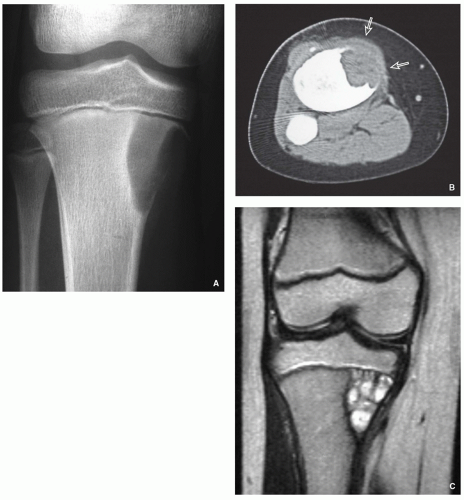

Radiography shows eccentric lytic lesion with geographic type of bone destruction without sclerotic border extending into the articular end of bone, commonly without periosteal reaction (Figs. 7.1 and 7.2); lack of matrix mineralization; internal trabeculations may be present (Fig. 7.3); occasionally “soap-bubble” appearance; invasion of the cortex and soft-tissue mass may be seen (Fig. 7.4).

Scintigraphy invariably shows increased uptake of the radiopharmaceutical agent (see Fig. 7.7B). In about 50% of cases, an abnormal pattern of uptake resembling a doughnut was observed.

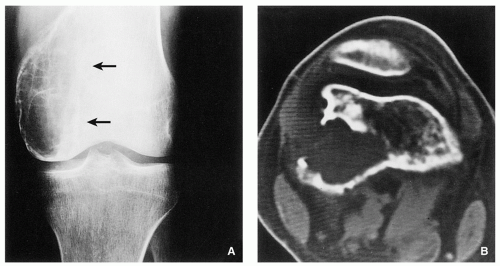

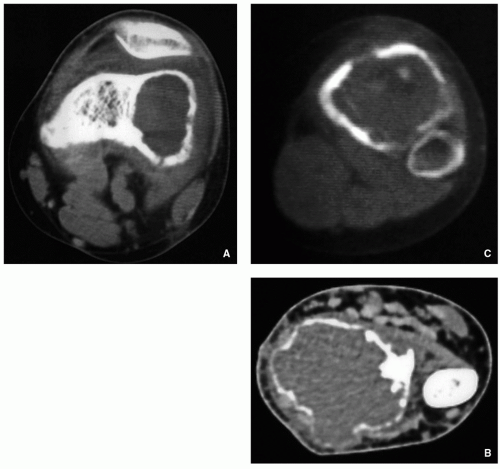

Computed tomography may outline the tumor extension and delineate better the cortical destruction (Figs. 7.5, 7.6 and 7.7).

Pathology:

Gross (Macroscopy):

Tumor tissue is usually soft and reddish brown, with occasional yellowish areas of xanthomatous change and firmer whitish areas representing fibrosis (Fig. 7.11).

Cystic and hemorrhagic spaces may be seen mimicking aneurysmal bone cyst.

Histopathology:

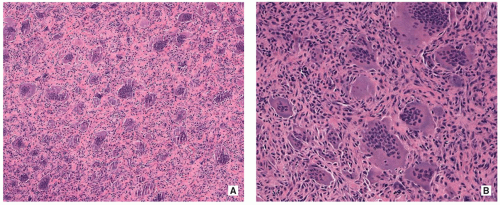

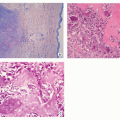

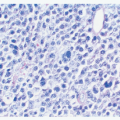

Tumor is composed of dual population of fibrocytic or monocytic round to oval in shape polygonal or elongated mononuclear stromal cells mixed with numerous evenly distributed, different in size, large osteoclast-like giant cells, which contain 20 to 100 nuclei (Figs. 7.12 and 7.13).

FIGURE 7.1 (Continued). (C) Anteroposterior and (D) lateral radiographs of the left knee of a 58-year-old man show eccentric osteolytic expansive lesion of the medial femoral condyle.

The giant cells, unlike normal osteoclasts, do not possess a ruffled border and are not apposed to bone surfaces.

It is generally accepted that the characteristic large osteoclast-like giant cells are not neoplastic.

Mononuclear cells, arising from primitive mesenchymal stromal cells, represent the neoplastic component.

Nuclei of the mononuclear stromal cells are very similar to those of the giant cells, having an open chromatin pattern and contain one or two small nucleoli.

The cytoplasm is ill defined, and there is sparse intercellular collagen.

Mitotic figures are invariably present, but no atypical mitoses are present.

Fibrous histiocytoma-like storiform pattern may occasionally be seen.

Secondary aneurysmal bone cyst changes may occur in 10% of cases.

One-third of cases show presence of intravascular plugs, particularly at the periphery of the tumor.

Areas of necrosis and hemorrhage, and occasional groups of foam cells and hemosiderin-laden macrophages may be present in large lesions.

Small foci of reactive osteoid or bone formation may be seen, especially after a pathologic fracture of the tumor or prior biopsy.

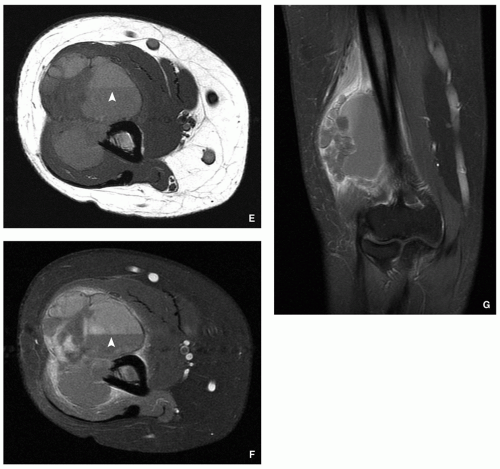

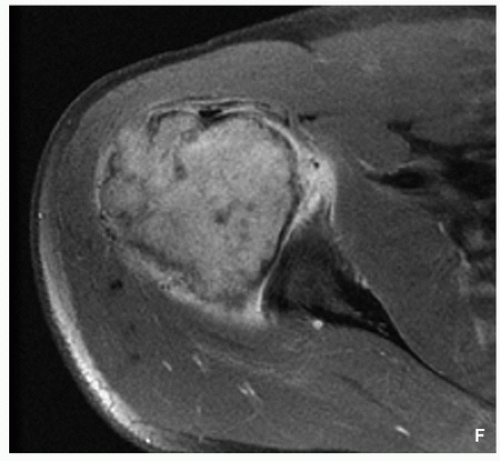

FIGURE 7.7 (Continued). (F) Axial T1-weighted fat-suppressed MR image obtained after intravenous administration of gadolinium shows heterogeneous enhancement of the tumor.

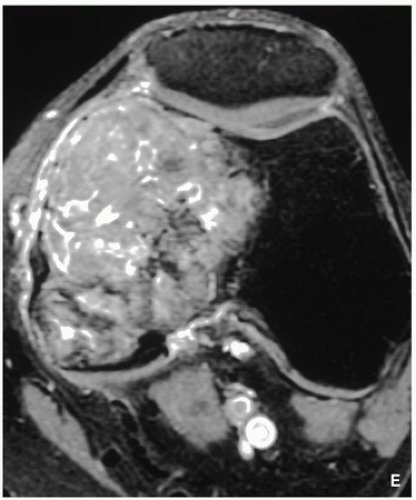

FIGURE 7.10 (Continued). (E) Axial T1-weighted fat-suppressed MRI obtained after intravenous administration of gadolinium shows significant enhancement of the tumor.

Reactive woven bone formation can be present in oldstanding tumors.

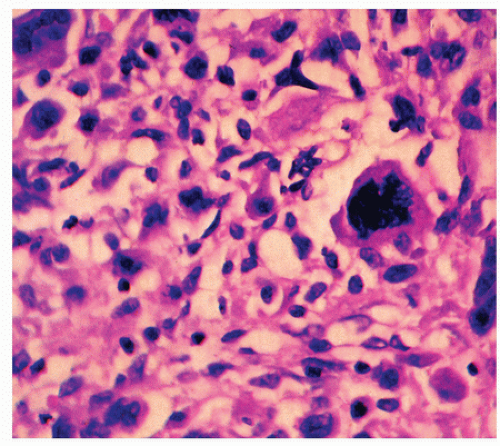

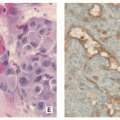

Atypical mitotic figures and the presence of pleomorphic cells may indicate malignant transformation (Fig. 7.14).

Genetics:

Telomeric associations (end-to-end fusions of apparently intact chromosomes) are the most frequent chromosomal aberration.

Telomeres most commonly affected are 11p, 13p, 14p, 15p, 19q, 20q, and 21p.

Some tumors showed rearrangement of chromosomes 16q22 and 17p13.

Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of 1p, 3p, 5q, 9q, 10q, and 19q has been reported.

Prognosis:

Giant cell tumor is locally aggressive and occasionally produces distant metastases.

Histopathologic features do not predict the extent of local aggression or local recurrence rate.

Local recurrence occurs in approximately 25% of patients and is usually seen within 2 years.

Pulmonary metastases may be seen in 2% of the patients on average 3 to 4 years after original diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis:

▪ Aneurysmal bone cyst

Imaging studies show invariably presence of periosteal reaction in form of a well-defined buttress; sclerotic margin is a common feature; fluid-fluid levels on MR imaging is characteristic.

Histopathology may show giant cells, but they are smaller than those of giant cell tumor and are in clusters rather than being evenly distributed; fibrous cell proliferation is often associated with strands of irregular islands of osteoid or bone.

▪ Intraosseous ganglion

Imaging may be similar to the giant cell tumor, since the intraosseous ganglion is radiolucent, eccentric, and located at the articular end of bone but, unlike GCT, invariably exhibits sclerotic margin; MRI shows no fluid-fluid levels.

Histopathologic studies show lack of typical features of GCT, such as dual population of fibrocytic or monocytic mononuclear stromal cells and evenly distributed osteoclast-like giant cells.

▪ Fibrosarcoma

Imaging appearance of some lesions may be similar to the giant cell tumor; however, involvement of the articular end of bone is uncommon.

Histopathology showing fascicles of spindle cells exhibiting characteristic “herringbone tweed” pattern is diagnostic.

▪ Plasmacytoma

Imaging appearance of some lesions may be similar to the giant cell tumor; however, the lesion is commonly central and not eccentric in location within the bone; involvement of the articular end of bone is unusual; the tumor affects much older population than giant cell tumor.

Histopathology showing sheets of closely packed cells, which resemble normal plasma cells with eccentric nuclei; clustered chromatin with cartwheel pattern and prominent nucleoli; and abundant, dense basophilic cytoplasm, coupled with characteristic immunohistochemistry findings showing positivity for CD138, CD38, and MUM1, is diagnostic.

▪ Osteolytic metastasis

Imaging appearance of solitary metastatic lesion may be very similar to giant cell tumor; soft-tissue mass, however, is less common; generally, metastatic lesion does not extend into articular end of bone; metastases are present in much older population.

Histopathology occasionally showing the origin of metastatic lesion, and immunohistochemistry studies (particularly application of cytokeratins), are diagnostic.

▪ Brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism

Solitary lytic bone lesion representing brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism may look on the imaging studies similar to the giant cell tumor; however, MRI shows often low signal intensity of the lesion, reflecting magnetic susceptibility to hemosiderin; other features of hyperparathyroidism including osteopenia, subperiosteal and chondral resorption, and softtissue calcifications are also helpful in the differential diagnosis.

Histopathology showing clusters of multinucleated giant cells within fibroblastic and reactive stroma in addition to clumps of hemosiderin pigment is diagnostic.

Simple Bone Cyst (SBC)

Definition:

Intramedullary, tumor-like lesion of unknown cause, attributed to local disturbance of bone growth, usually unilocular cyst filled with serous or serosanguineous fluid.

Epidemiology:

Represents approximately 3% of all primary bone lesions.

Eighty percent of patients are in the first two decades of life.

Male-to-female ratio of 3:1.

Sites of Involvement:

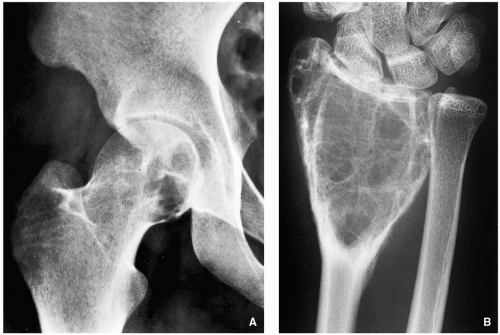

Any bone can be affected with most common locations of the proximal humerus followed by the proximal femur and proximal tibia.

Metaphysis and proximal diaphysis are the most common sites in the long bone.

Clinical Findings:

May be asymptomatic.

The first symptom may be a pathologic fracture.

Pain and local swelling.

Imaging:

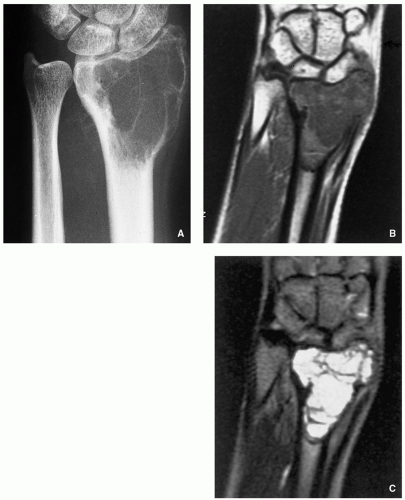

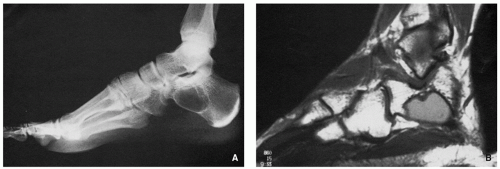

Radiography shows centrally located, well-circumscribed radiolucent lesion with sclerotic margins (Figs. 7.15, 7.16, 7.17, 7.18 and 7.19) and absence of periosteal reaction (unless there has been a pathologic fracture); “fallen fragment” sign is a diagnostic feature (see Fig. 7.19).

Magnetic resonance imaging shows intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted sequences and homogenously high signal on T2-weighted and other water-sensitive sequences (Figs. 7.20 and 7.21).

Pathology:

Gross (Macroscopy):

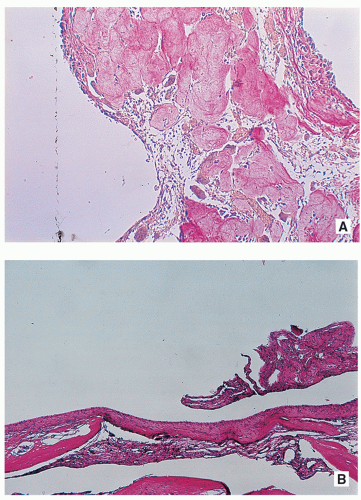

Well-demarcated cystic cavity with glistening membrane, and occasionally thin grayish-white fragments (Fig. 7.22).

Histopathology:

Cyst’s wall consists of a thin layer of fibrous tissue composed of scattered fibroblasts and collagen fibers, with occasionally a flattened single-cell lining (Fig. 7.23).

Pathologic fractures may cause reactive changes and result in the presence of numerous reactive fibroblasts, osteoclast-type giant cells, hemosiderin deposits, and reactive woven bone.

Genetics:

Clonal rearrangements involving chromosomes 4, 6, 8, 16, and 21.

Translocation t(16;20)(p11.2;q13) has been described.

Prognosis:

Recurrence after surgical treatment has been reported in about 10% to 20% of cases, especially in children.

Growth arrest of the affected bone and avascular necrosis of the head of the femur after pathologic fracture have been reported.

Spontaneous healing after pathologic fracture has been reported.

Differential Diagnosis:

▪ Aneurysmal bone cyst

Imaging studies show eccentric location of the lesion and periosteal reaction in the form of a buttress; MRI shows fluid-fluid levels.

Histopathology shows solid areas containing giant cells and fibrous cell proliferation often associated with strands of irregular islands of osteoid or bone.

▪ Nonossifying fibroma

Imaging studies show the lesion to be eccentric in location, commonly with lobulated, thick sclerotic border, and magnetic resonance imaging exhibits features of a solid, not cystic, lesion.

Histopathology showing bland monomorphous spindle cells admixed with histiocytic cells commonly arranged in a swirling storiform pattern is diagnostic.

▪ Monostotic fibrous dysplasia

Radiography shows characteristic rind sign; occasionally noted are focal calcifications.

Magnetic resonance imaging exhibits features of a solid, not cystic, lesion.

Histopathology showing metaplastic woven bone trabeculae resembling Chinese characters without osteoblastic activity is diagnostic.

Aneurysmal Bone Cyst (ABC)

Definition:

Benign multiloculated, blood-filled cystic mass that is often expansive and locally destructive; may arise de novo in bone or may arise secondary within various benign and malignant osseous lesions.

Primary aneurysmal bone cysts account for approximately 70% of all cases.

Majority of secondary ABC arise in association with benign lesions, most commonly giant cell tumor of

bone, chondroblastoma, osteoblastoma, chondromyxoid fibroma, and fibrous dysplasia, and less frequently, osteosarcoma or chondrosarcoma.

Epidemiology:

Affects all age groups, but most common during the first two decades of life, 76% of cases occurring in patients younger than 20 years.

No sex predilection.

Sites of Involvement:

May affect any bone, but usually arises in the metaphysis of the long bones.

Most common locations are the femur, tibia, humerus, and posterior elements (neural arch) of the vertebra.

Clinical Findings:

Pain and local swelling.

Occasionally, a pathologic fracture may be the first symptom.

Neurologic symptoms if lesion is located in the spine.

Imaging:

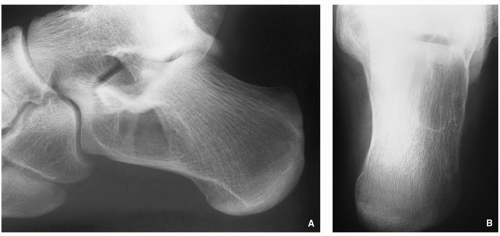

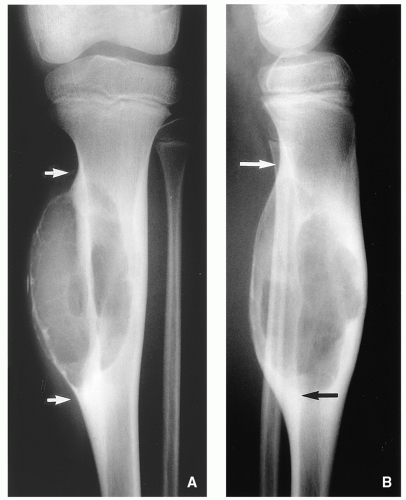

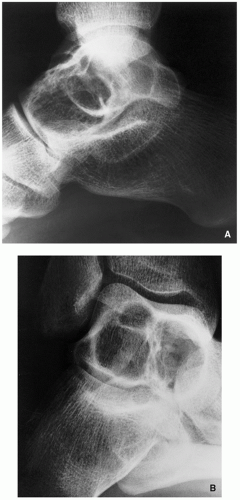

Radiography shows an eccentric, multicystic radiolucent lesion, commonly expansive, with buttress of periosteal reaction; narrow zone of transition and geographic type of bone destruction are characteristic features (Figs. 7.24, 7.25, 7.26 and 7.27); soft-tissue extension may be present (Fig. 7.28, see also Fig. 7.32).

Skeletal scintigraphy shows increased uptake of radiopharmaceutical tracer (see Figs. 7.30 and 7.31).

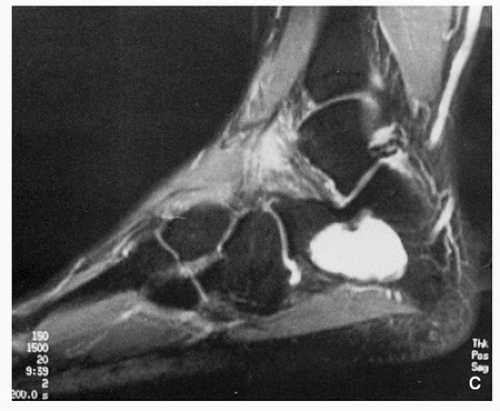

FIGURE 7.20 (Continued). (C) Sagittal T2-weighted MR image demonstrates homogeneous high signal intensity of the fluid-filled cyst.

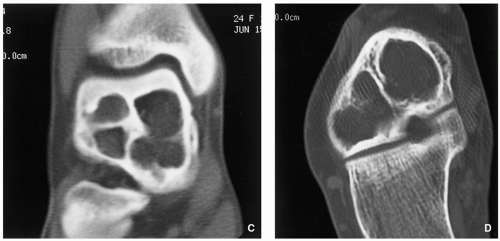

Computed tomography shows to better advantage the internal ridges and may demonstrate a shell of periosteal reaction surrounding the soft-tissue mass, not always well shown on the conventional radiography (Figs. 7.29, 7.30, 7.31, 7.32 and 7.33).

Magnetic resonance imaging shows cystic cavities exhibiting fluid-fluid levels (see Figs. 7.31E,F, 7.33C, 7.34E,F, and 7.35B). The wide range of signal intensities within the cyst on both T1- and T2-weighted images is probably due to settling of degraded blood products and reflects intracystic hemorrhages of different ages (Figs. 7.31, 7.32, 7.33, 7.34 and 7.35).

Pathology:

Gross (Macroscopy):

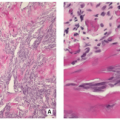

Well-defined sponge-like mass composed of multiple, blood-filled spaces separated by thin, tan-white septa; solid foci of various size may be present (Fig. 7.36).

Histopathology:

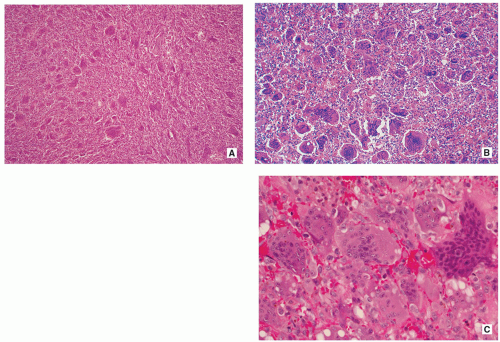

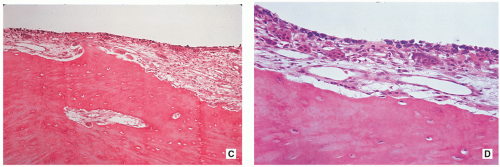

Well circumscribed and composed of blood-filled cystic spaces lined by a single layer of flat undifferentiated cells (that react negatively with all endothelial markers), separated by fibrous septa, alternating with solid areas (Figs. 7.37 and 7.38).

Fibrous septa are composed of uniform plump fibroblasts (which may show active mitoses without atypia), multinucleated osteoclast-like giant cells, usually in clusters (sometimes they look like “jumping into swimming pool” of cystic spaces), and reactive woven bone rimmed by osteoblasts (Fig. 7.39).

FIGURE 7.21 (Continued). (C) Sagittal STIR MRI shows the lesion exhibiting homogeneous high signal intensity consistent with fluid content.

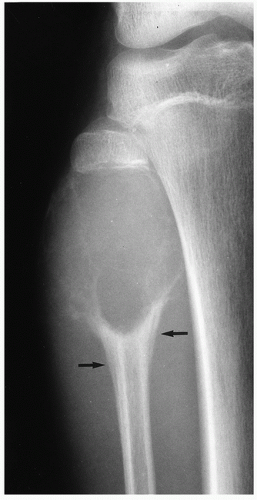

FIGURE 7.27 Radiography of aneurysmal bone cyst. A large, radiolucent expansive lesion in the proximal fibula of an 11-year-old girl reveals a buttress of periosteal reaction (arrows).

FIGURE 7.29 (Continued). (C) and through the posterior and middle subtalar joint facets (D) demonstrate the internal ridges of the lesion to better advantage.

Solid tissue surrounding vascular spaces is composed of fibrous, richly vascular connective tissue (Figs. 7.40 and 7.41).

Some of the reactive bone is basophilic and has been called “blue bone.”

Deposits of iron pigment are common findings.

Atypical mitotic figures are absent (if, however, present, diagnosis of telangiectatic osteosarcoma should be contemplated).

Necrotic areas are rare, unless there was a prior pathologic fracture.

Genetics:

Rearrangements of the USP6 (ubiquitin-specific peptidase 8/Tre-2) gene at chromosome 17q13.

Clonal rearrangements of chromosome bands 16q22 and 17p13.

Chromosome translocation t(16;17)(q22;p13).

Prognosis:

Recurrence rate following curettage is variable (20% to 70%).

Differential Diagnosis:

▪ Simple bone cyst

Imaging studies show central location in bone and lack of “ballooning,” periosteal reaction, or soft-tissue extension. If a pathologic fracture occurs, the “fallen fragment” sign is diagnostic.

Histopathology shows thin layer of fibrous tissue composed of scattered fibroblasts and collagen fibers covering the cyst’s wall; however, solid areas with significant number of giant cells are not present.

FIGURE 7.32 Radiography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging of aneurysmal bone cyst. (A)

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

|