LEARNING OBJECTIVES

1. Diffuse changes in the breasts on mammography, ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

2. Benign causes of diffuse changes in the breast

3. Malignant causes of diffuse changes in the breast

4. Inflammatory breast cancer versus locally advanced breast cancer

5. Descriptors for parenchymal asymmetry

6. Differential consideration for parenchymal asymmetry

7. Clinical, imaging, and histological findings in Paget disease

8. Lobular neoplasia: risk marker or precursor?

9. Controversies regarding the management of patients of lobular neoplasia

10. Approach to the management of patients with a solitary dilated duct

11. Dilated vasculature

12. Clinical and imaging findings in patients with Mondor disease

DIFFUSE BREAST CHANGES

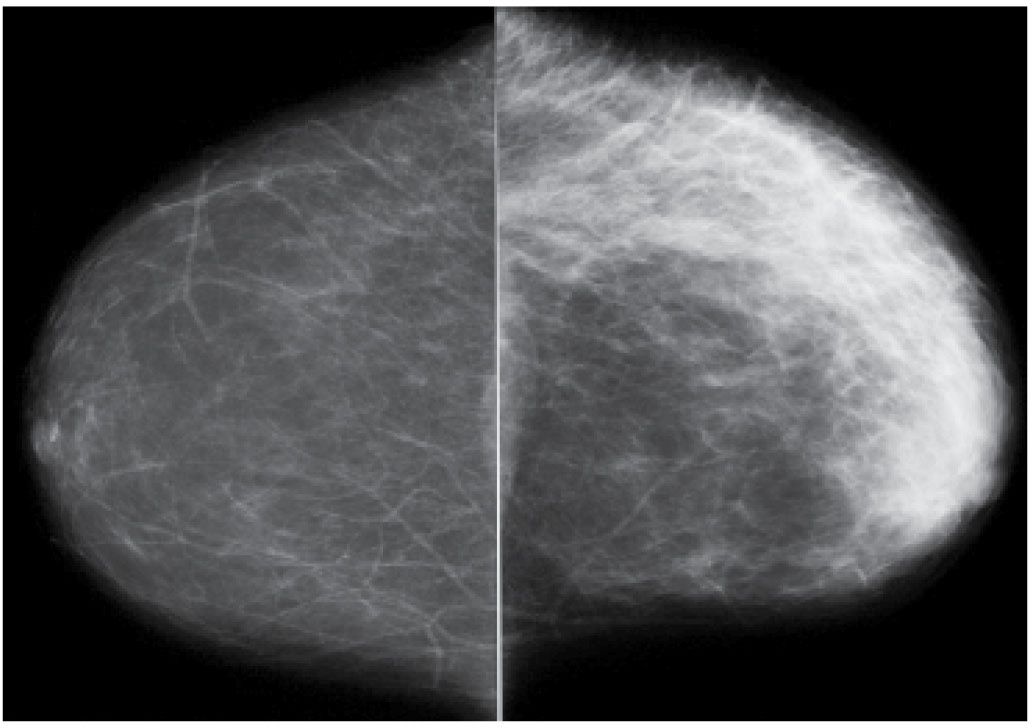

Changes that affect the breasts diffusely can be difficult to perceive on a mammogram, particularly if the process is bilateral and evolving slowly. In reviewing mammograms, prepare your brain to perceive these changes by specifically asking yourself: Are the breasts symmetric in size and density? Is there prominence of the trabecular markings? Is there a contrast difference between the breasts? How thick are the breasts (cm of compression), and is compressibility different between the breasts? What technical factors were used for the exposure, and are they different for one view or side compared with the other(s)? Have the technical factors changed from one year to the next? Comparison with prior films can be helpful if studies are viewed in sequence. Diffuse changes are characterized by increases in the overall density of the breast parenchyma, thickening of the trabecular pattern (“Kerley B lines”), and skin thickening. In some women, increases or decreases (shrinking) in the perceived size of the breast accompany these changes. On digital images, the conspicuity of the skin is such that skin thickening can be detected easily. The overall compressibility of the breast may be decreased, and the techniques needed to penetrate the thickened skin, and possibly edematous tissue, increase. As kVp is increased to penetrate the tissue adequately, contrast decreases.

Skin thickening is appreciated readily on ultrasound, though it may require the use of a standoff pad: The hypoechoic central band of the skin increases in width. The deep hyperechoic stripe may not be apparent or appears disrupted. Anastomosing lymphatic channels seen as hypo- to anechoic thin tubular structures may be identified just deep to the deep hyperechoic stripe of the skin. Flow may be seen in some of these structures with Doppler. Associated disruption of the normal breast architecture, loss of normal tissue planes, increases in tissue echogenicity, and, in some patients, focal findings may also be seen on ultrasound. During real-time scanning, pitting edema may be noted related to the pressure applied on the breast with the transducer.

On physical examination, peau d’orange changes reflecting edema may be apparent diffusely involving the breast or, less commonly, localized to the dependent portion of the breast. Depending on the underlying cause of the diffuse change, additional findings including erythema, ecchymotic areas, and increased warmth of the affected breast, variable amounts of tenderness may be elicited. Benign and malignant causes of diffuse breast changes (1–3) are listed in Table 9.1.

Radiation Therapy Effect

Radiation therapy (XRT) is probably one of the most common benign causes of diffuse changes in the breast. It is typically unilateral, limited to the treated breast. On physical examination, the breast is “tanned”; there may be associated tenderness, and surgical changes are present at the lumpectomy site and, commonly, the axilla. Distortion, spiculation, and metallic clips at the lumpectomy site accompany skin and trabecular thickening (Fig. 9.1); similar findings may be seen in the axilla, reflecting the sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy site. Diffuse changes are typically seen in the acute setting and slowly resolve over the first 2 years following completion of the radiation therapy. Residual skin thickening is seen in 20% to 40% of patients 2 years after the lumpectomy (4–6). Increases in density, combined with trabecular and skin thickening, that develop after the first 2 years following radiation therapy need to be evaluated carefully, and may warrant an MRI and biopsy, to exclude recurrent disease. Interestingly, even though the affected breast is less compressible and a higher kVp is needed to penetrate the two layers of thickened skin, in many patients, contrast may be perceived as increased on the affected side.

Table 9.1 DIFFERENTIAL: DIFFUSE BREAST CHANGES

Benign | Malignant |

Radiation therapy

Fluid overload Cardiac etiology (CHF) Renal disease

Dialysis catheter shunt Trauma

Mastitis Hormone replacement therapy Axillary adenopathy with lymphatic obstruction Superior vena cava obstruction (SVC syndrome) PASH (rare) Granulomatous mastitis (rare) Giant cell arteritis (rare) Scleroderma (rare) | Invasive ductal carcinoma (locally advanced) Invasive lobular carcinoma (shrinking or enlarging breast) Inflammatory carcinoma (infiltrating ductal carcinoma) DCIS Recurrence after conservative breast cancer treatment Lymphoma |

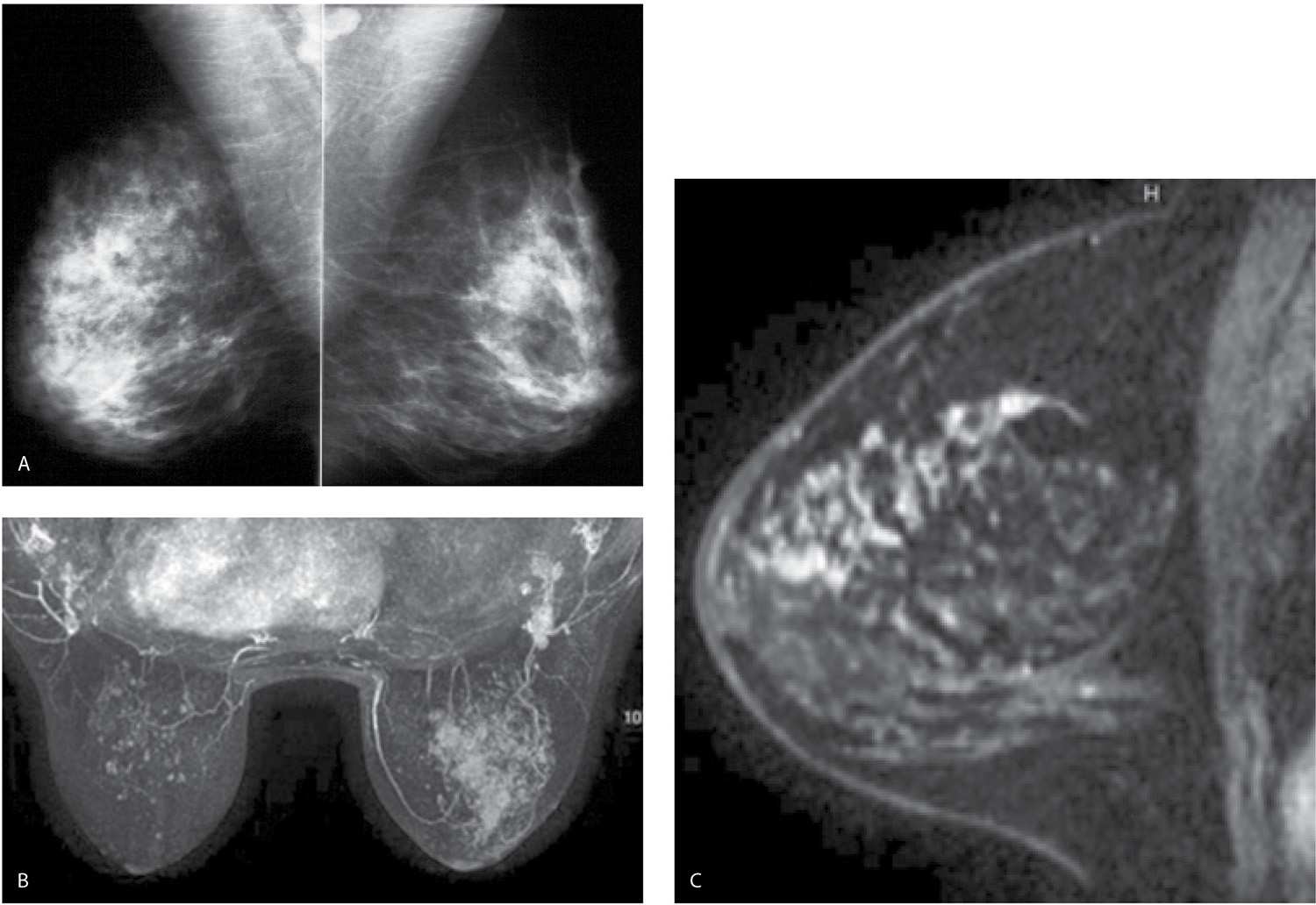

In addition to localized findings at the lumpectomy site (nonenhancing soft tissue or a mass with distortion), skin thickening and variable amounts of edema (see Figs. 11.30C and 11.33C, D) are seen on MRI acutely; the radiated breast is often relatively “quiescent” compared with the contralateral normal breast for years following XRT (Fig. 9.2; also see Fig. 5.11).

Fluid Overload

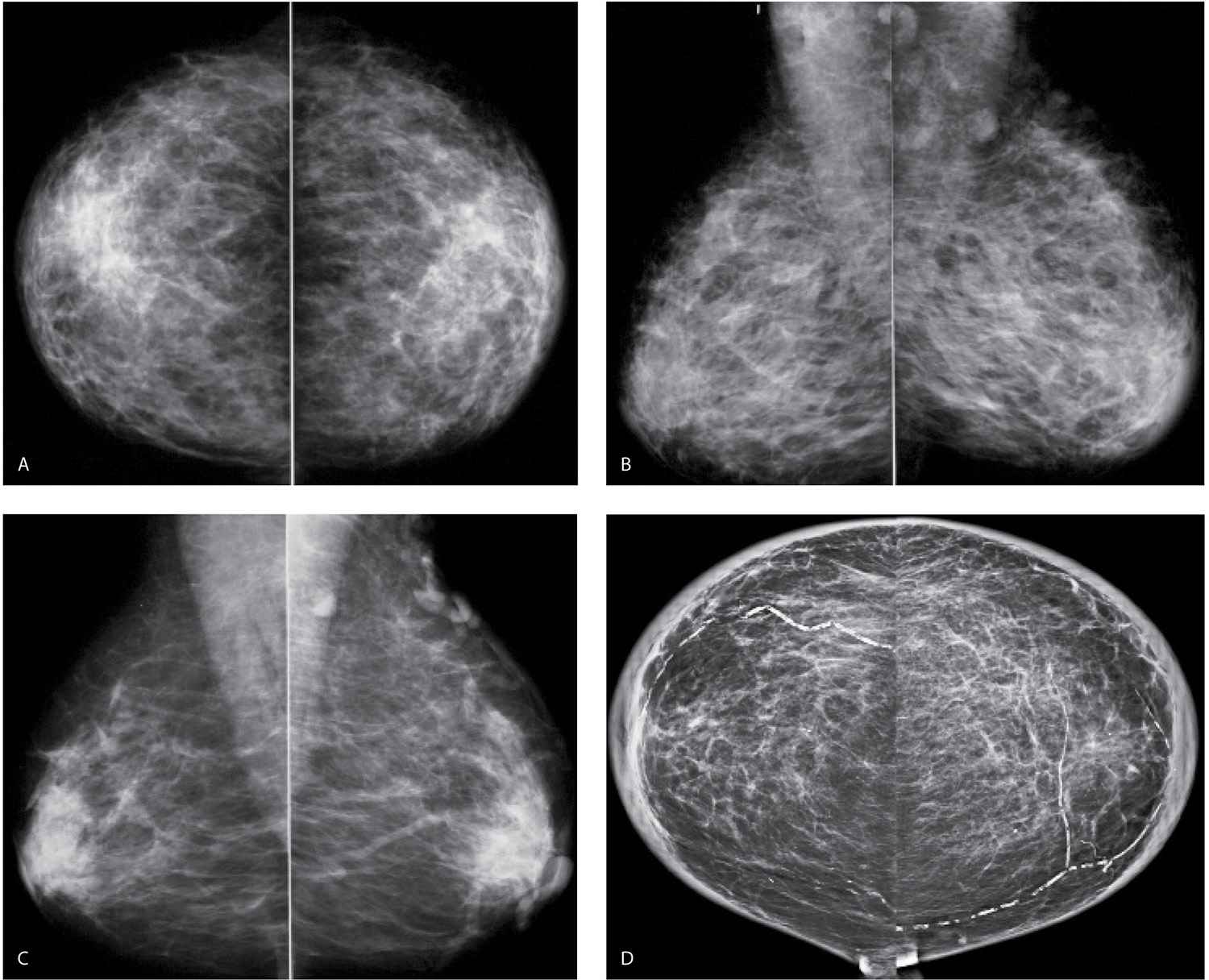

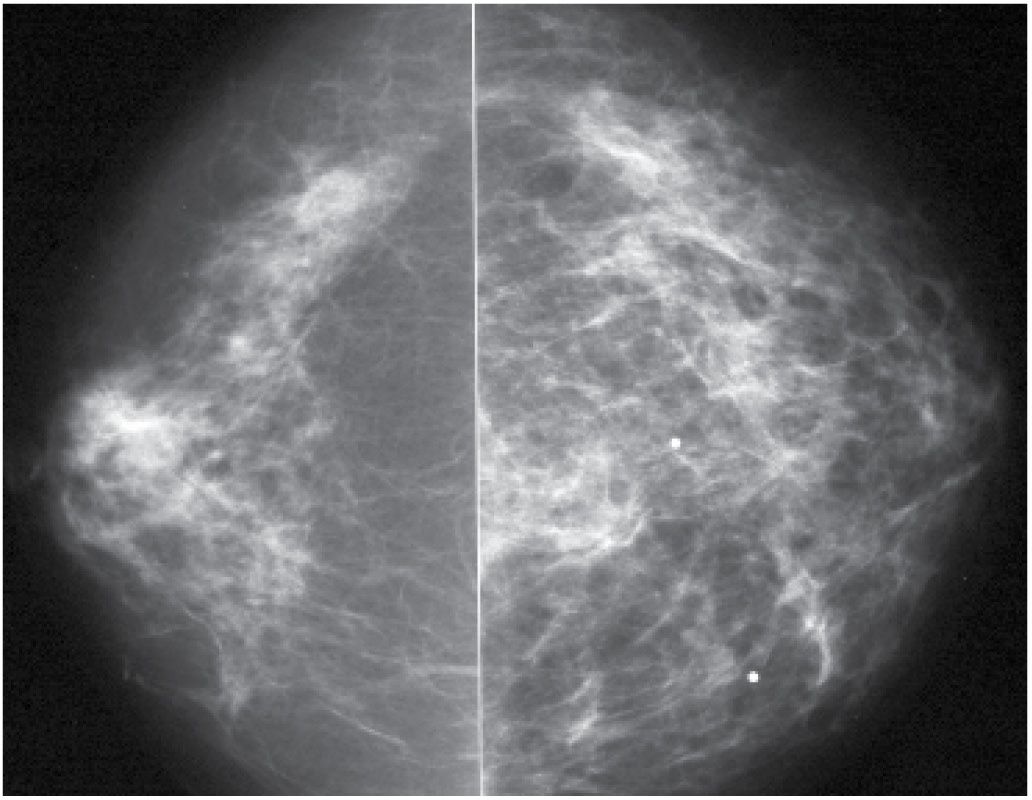

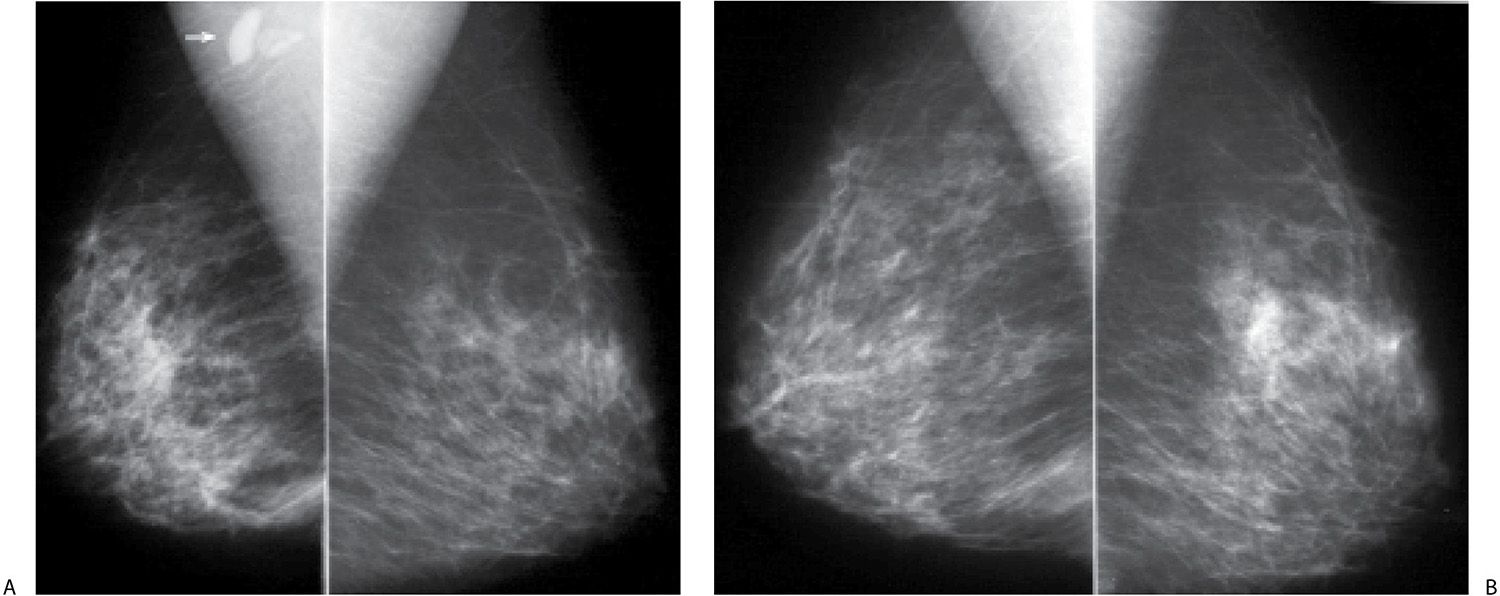

Patients with fluid overload (congestive heart failure, end-stage renal disease) can present with bilateral (Fig. 9.3), less commonly unilateral (Fig. 9.4), prominence of the trabecular markings and skin thickening (Fig. 9.3B). More recently, we have seen a number of patients with dialysis catheter shunts in an arm presenting with unilateral changes diffusely involving the ipsilateral breast (Fig. 9.5). Obtaining technically acceptable images with no blurring is made more difficult in some of these patients because of shortness of breath. Peripheral edema and shortness of breath may be apparent clinically. Patients may describe some tenderness, particularly with compression. With successful treatment of the underlying etiology, the peripheral edema and changes noted in the breasts can resolve rapidly. If the patient is lying preferentially on one side for long periods of time, the edema may be more pronounced or limited to the dependent breast. With significant congestive heart failure, the periareolar region can become quite dense on the mammogram (Fig. 9.6); this is a finding we have not seen with too many other conditions.

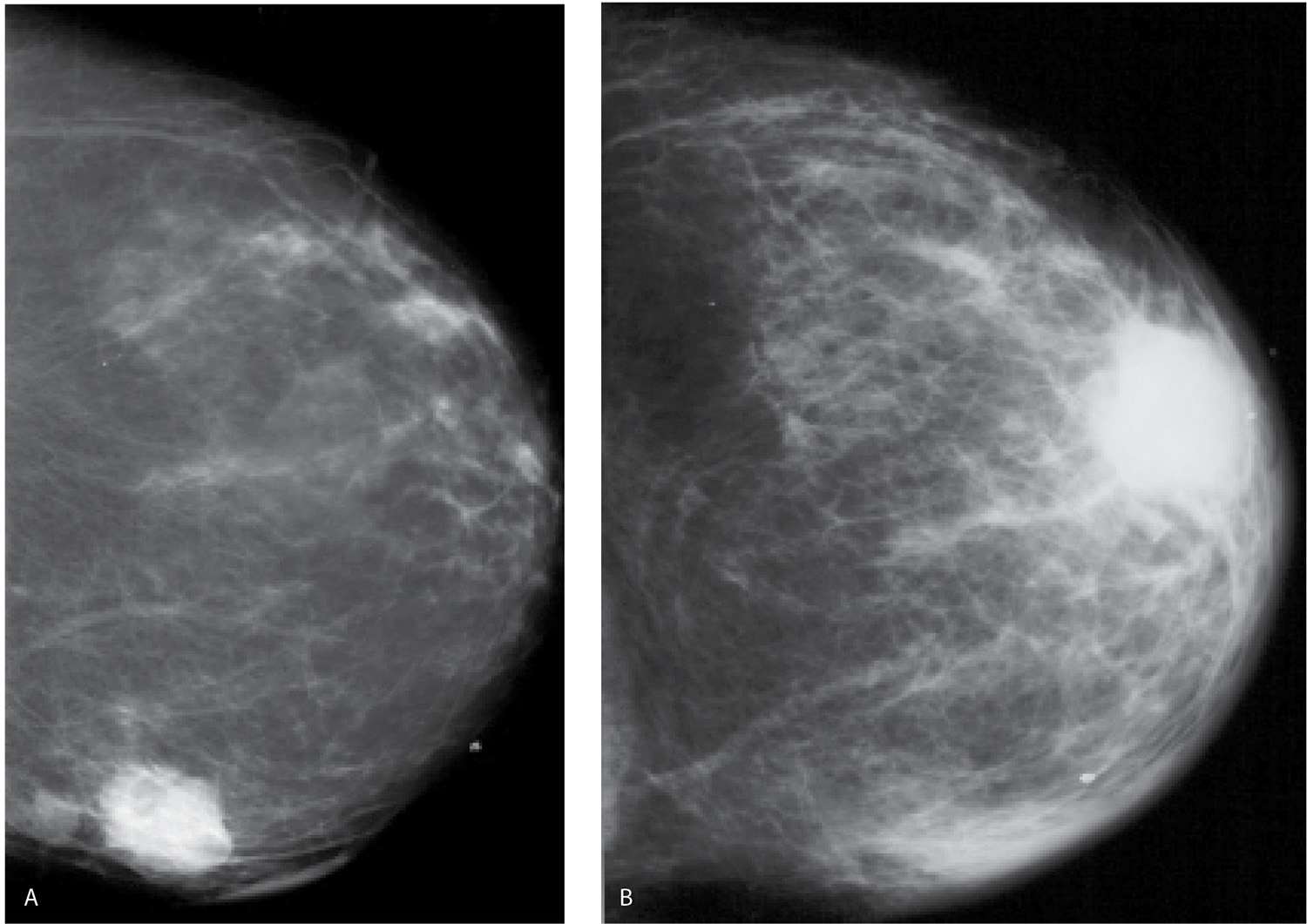

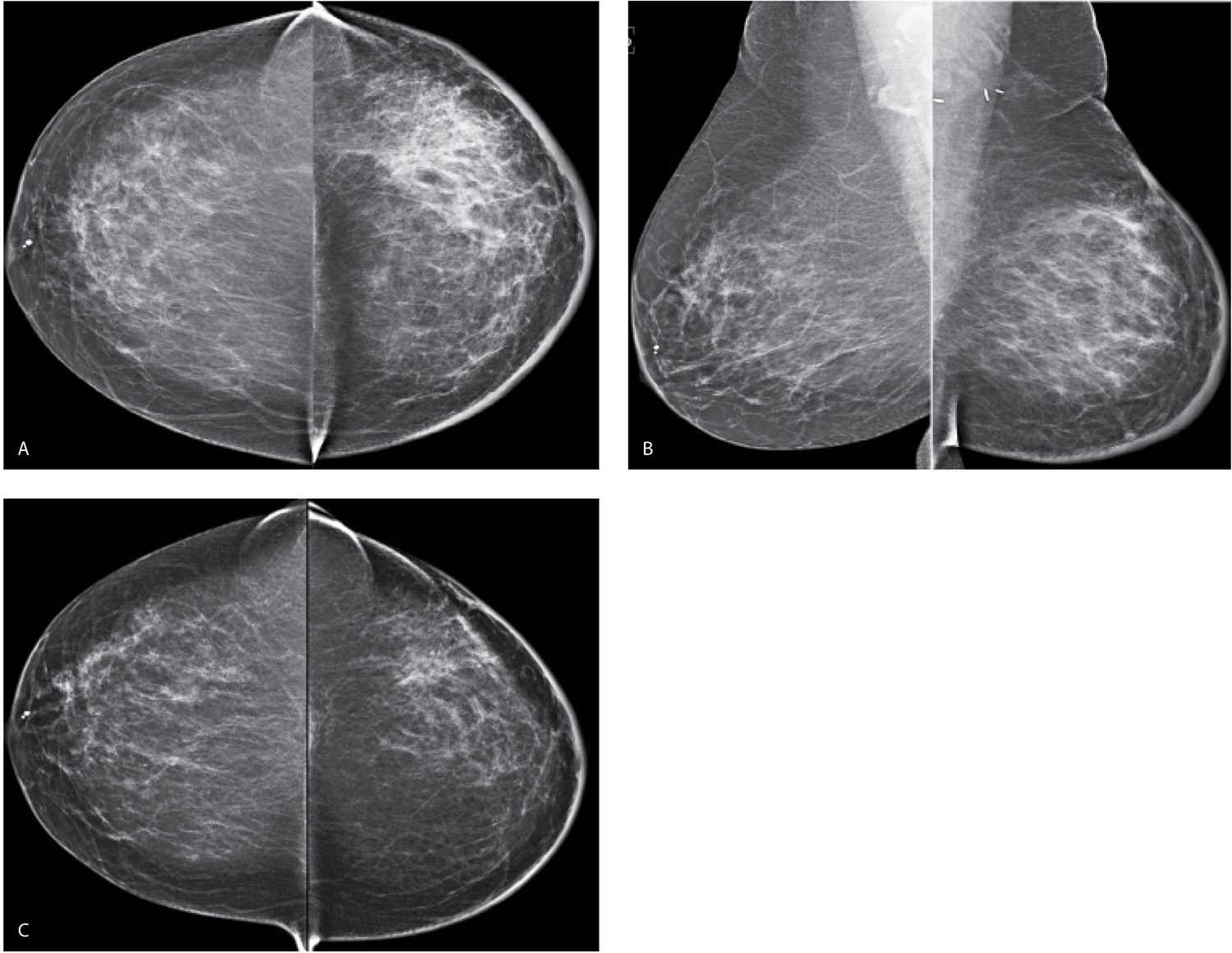

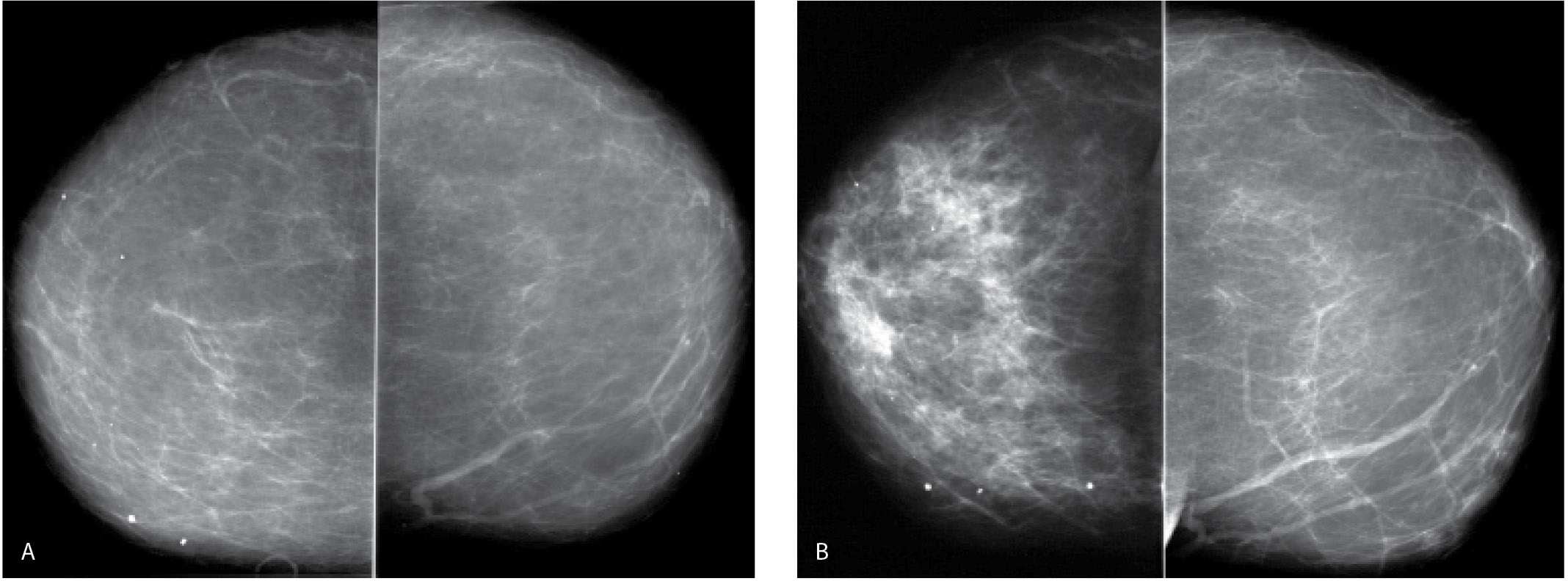

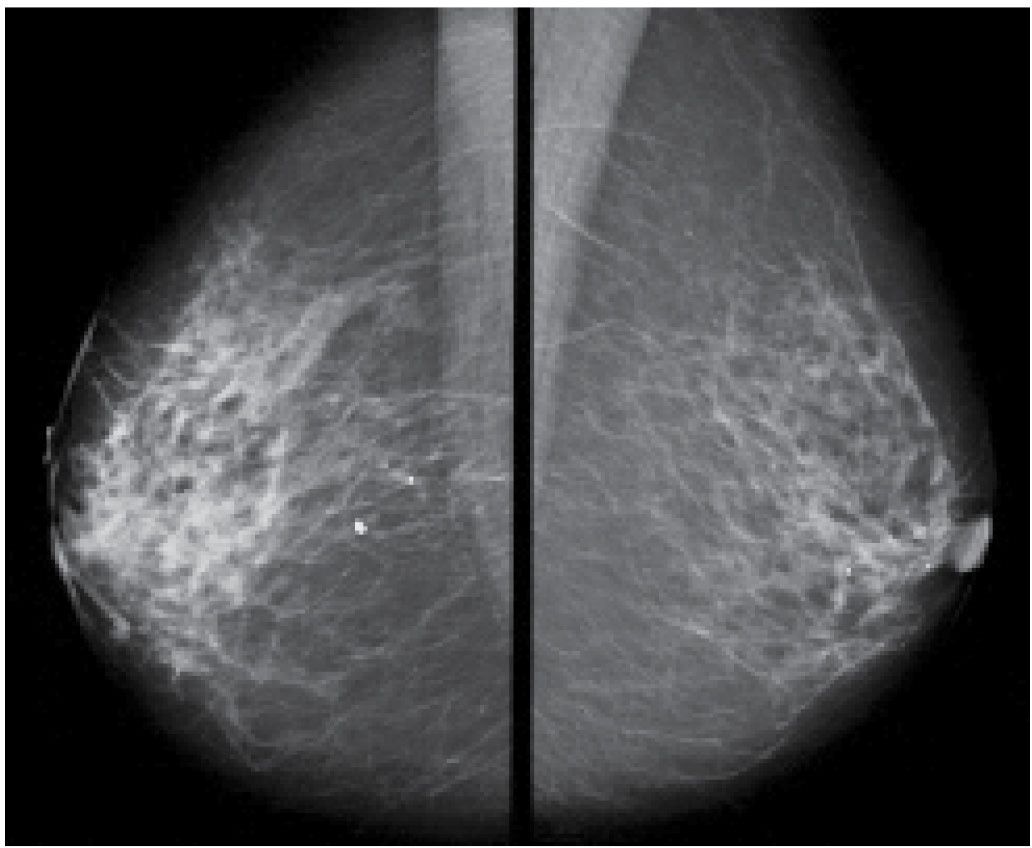

FIG. 9.1 • Radiation therapy effect. Craniocaudal (CC) (A) and Mediolateral oblique (MLO) (B) views in a 55-year-old woman 7 months following completion of radiation therapy. The left breast is smaller and characterized by increased density, diffuse prominence of the trabecular and skin thickening, as well as surgical clips in the lower aspect of the axilla. Notice the increased contrast of the left breast. Morphologically normal-appearing lymph nodes are noted in the axillae. C: CC views 1 year following those shown in part A, 19 months following the completion of radiation therapy. The asymmetry in breast size is less apparent. The overall density of the left breast is decreasing, as is the prominence of the trabecular markings and skin thickening. A small area of distortion and focal skin retraction persist at the lumpectomy site.

FIG. 9.2 • Radiation therapy effect. Magnetic resonance imaging maximum-intensity projection image. Do you notice any difference between the breasts? In this patient, the right breast is larger with scattered foci of nonspecific enhancement and prominent venous structures. The left breast is smaller and quiescent following lumpectomy and radiation therapy. Although not shown, nonenhancing increased soft tissue, distortion, and focal skin retraction are present at the lumpectomy site in the left breast.

FIG. 9.3 • Fluid overload. CC (A) and MLO (B) views on a 39-year-old patient with end-stage renal disease on dialysis. The density of the breasts is increased, and there is marked prominence of the trabecular markings. This is best demonstrated on the oblique views with trabecular markings superimposed on the pectoral muscles (Kerley B lines). C: Previous MLO views in the same patient for comparison. When the process is diffuse and bilateral, it can be difficult to perceive the described changes. It is incumbent upon the interpreting radiologist to consider the possibility of diffuse change, review technical factors, and confirm the observations by reviewing the patient’s history, and, if available, comparing with prior studies (going back to the earliest studies available). D: CC views in a 61-year-old patient with congestive heart failure. The trabecular markings are thickened bilaterally with diffuse skin thickening readily appreciated on the digital images. Dense arterial calcifications are present bilaterally.

FIG. 9.4 • Fluid overload. CC views. Diffuse prominence of the trabecular markings and increased density is noted involving the left breast in a patient with a history of atrial fibrillation and diastolic congestive heart failure. In patients with fluid overload, the changes are usually bilateral; however, they may develop unilaterally if the patient preferentially lies on one side. When asymmetric, diffuse changes are more easily perceived.

Skin thickening, anastomosing lymphatic channels, and hyperemia are identified on ultrasound. Additionally, increased echogenicity of the tissue and disruption of normal soft tissue planes may be localized to the dependent portions of the breasts or may diffusely involve the breasts (Fig. 9.5B, C).

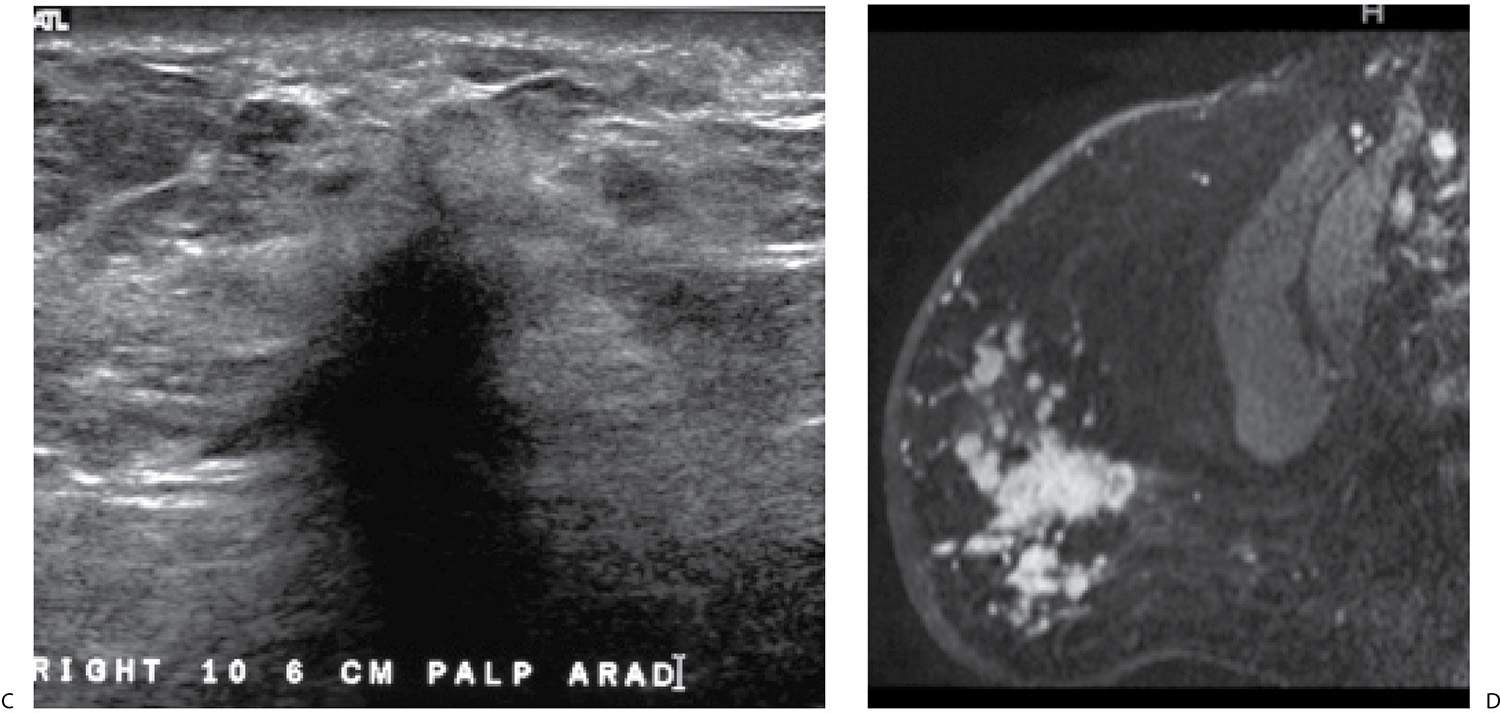

Trauma

Diffuse changes can be seen after significant trauma to the breasts, commonly following a motor vehicle accident with air bag deployment or a major fall. The changes may be unilateral or bilateral. These patients typically do not present in the acute setting but rather months (12–18 months) after the accident describing thickening, heaviness, skin changes, and pain in the affected breast. In addition to diffuse increases in density, prominence of the trabecular markings (Fig. 9.7A, B; also see Fig. 11.15) and possible skin thickening seen on the mammogram, fat necrosis and oil cysts with varying degrees of increased, irregular surrounding density and distortion as well as associated calcifications may be present (Fig. 9.7C). Skin thickening, loss of normal soft tissue planes with increased echogenicity of the tissue, and localized findings including complex cystic and solid masses may be identified on ultrasound (Fig. 9.7D). The extent and speed with which these changes resolve vary from patient to patient. See Chapter 11 for additional comments on trauma to the breast.

Mastitis

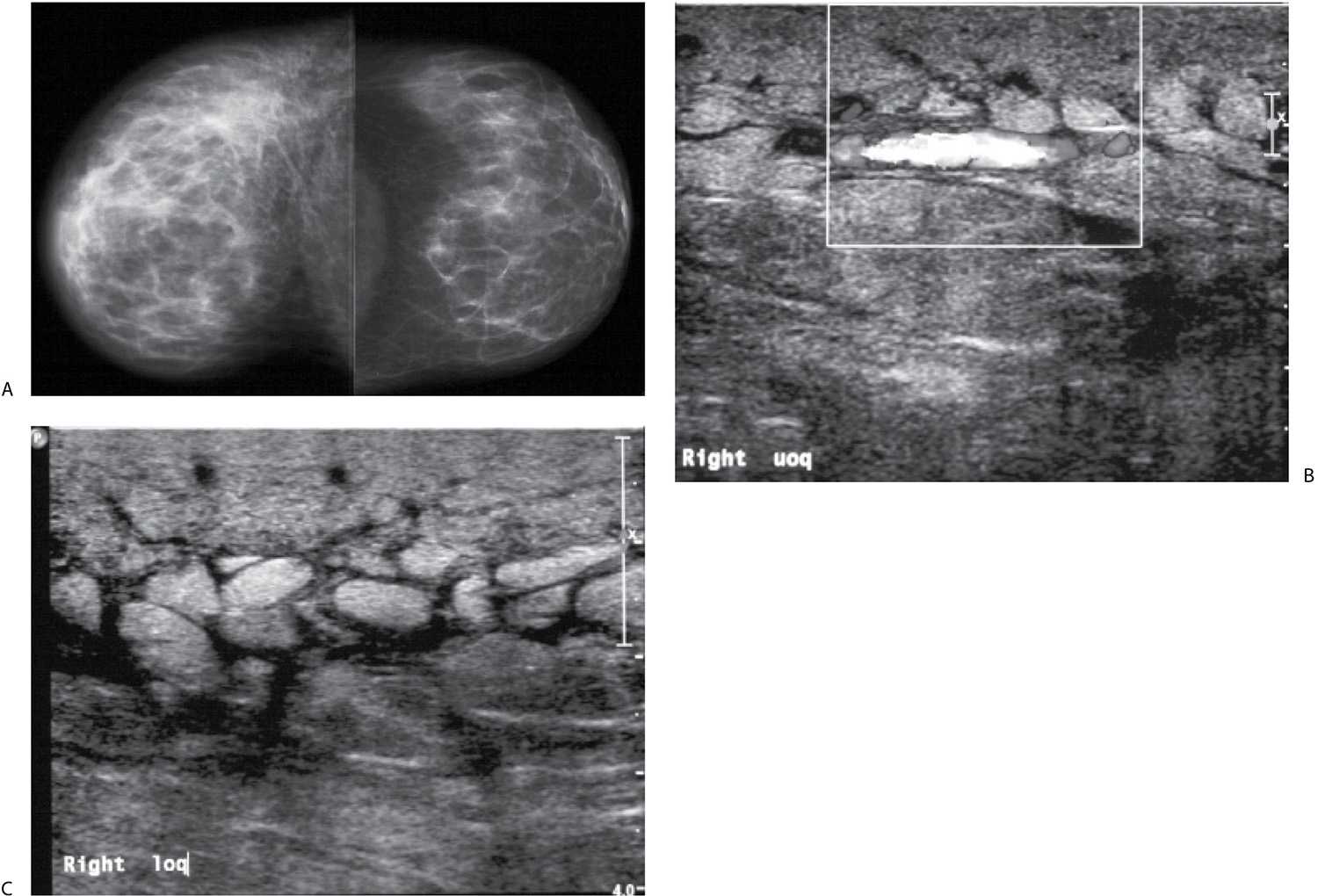

Patients with acute bacterial mastitis present with diffuse breast tenderness that may preclude an adequate mammogram because the patient is unable to tolerate significant compression. On physical examination, the affected breast is erythematous and warmer than the contralateral breast. If the patient tolerates the mammogram, diffuse increases in the density of the breast (Fig. 9.8A; also see Fig. 4.49A), prominence of the trabecular marking (Fig. 9.9A), skin thickening, and loss of compressibility may be present. On ultrasound, skin thickening may not be a prominent feature; however, increased echogenicity of the tissue with loss of normal soft tissue planes, hyperemia, and dilated lymphatics may be seen (Figs. 9.8B and 9.9B). Mastitis is relatively common in patients who are lactating; however, it can develop in women of all ages, some of whom may have a history of diabetes. An antibiotic that covers aerobic and anaerobic organisms is used in patients who are not lactating. We follow these patients closely to assure that an abscess requiring drainage does not develop and that there is complete resolution of the symptoms and findings following antibiotic therapy. Some patients require two courses of antibiotics for complete resolution.

FIG. 9.5 • Fluid overload. A: CC views. The patient presents with an increase in the size of her right breast following placement of a dialysis catheter shunt in her right arm. The right breast is larger than the left and demonstrates increased density and diffuse prominence of the trabecular markings. Note the loss of contrast related to the decreased compressibility and increased kVp needed to obtain an adequate exposure. B and C: Representative ultrasound images of the upper (uoq) and lower outer (loq) quadrants of the right breast. Skin thickening and anastomosing lymphatic channels are readily apparent in the subcutaneous tissue. Normal soft tissue planes are disrupted, and the echogenicity of the tissue is increased. When Doppler is turned on, flow can be appreciated in some of the larger tubular structures in the upper outer quadrant of the breast.

FIG. 9.6 • Congestive heart failure. Left CC view in an 89-year-old patient with left breast swelling. Increased density, diffuse trabecular thickening, and marked thickness and density in the periareolar region and anterior portion of the breast are present. Findings are bilateral but less pronounced on the right (not shown). (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

Axillary or Central Venous Obstruction

In more than 80% of patients, complete or partial obstruction of the superior vena cava is caused by superior mediastinal tumors, including adenocarcinoma of the lung, lymphoma, thyroid carcinoma, thymomas, and teratomas. Less common causes include chronic fibrotic mediastinitis that is idiopathic or secondary to tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, or drugs (e.g., methysergide); thrombophlebitis related to indwelling central venous catheters or pacemaker wires; aortic arch aneurysms and constrictive pericarditis. Symptoms include swelling of the neck and face, headaches, visual disturbances, and obstructive venous drainage of the head, neck, and upper extremities. Facial flushing and dilatation of anterior chest wall veins secondary to collateral flow may develop. Diffuse breast changes and dilated venous structures may be seen mammographically in these patients, more commonly involving the right breast; however, it can be a bilateral process. With a similar mechanism, axillary adenopathy with lymphatic obstruction can lead to diffuse breast changes limited to the ipsilateral breast.

Granulomatous Mastitis

Granulomatous mastitis is an uncommon cause of diffuse changes in the breast usually unilateral, though there are reports of bilateral involvement. Clinically, patients present with a mass that may be tender or, less commonly, diffuse breast tenderness in the absence of focal findings; rarely, they develop fistulas. Patients are relatively young, and in many, the disease presents within 6 years of pregnancy. The etiology is unknown; however, some have suggested an autoimmune reaction to extravasated lobular secretions, undetected organisms, or the use of oral contraceptives (7–10). In addition to diffuse changes in the affected breast (Fig. 9.10; also see Fig. 4.50), other reported mammographic findings include one or multiple masses, or areas of parenchymal asymmetry (11,12). On ultrasound, findings in granulomatous mastitis include multiple relatively circumscribed lesions with a tubular configuration or irregular hypoechoic lesions with shadowing. The findings on MRI are also nonspecific and include heterogeneously enhancing masses with indistinct margins, homogeneously enhancing nodules, or rim-enhancing masses, reflecting abscess formation. Kinetic curve analysis is nonspecific with variability among lesions. Reactive lymphadenopathy can be seen with all imaging modalities (12).

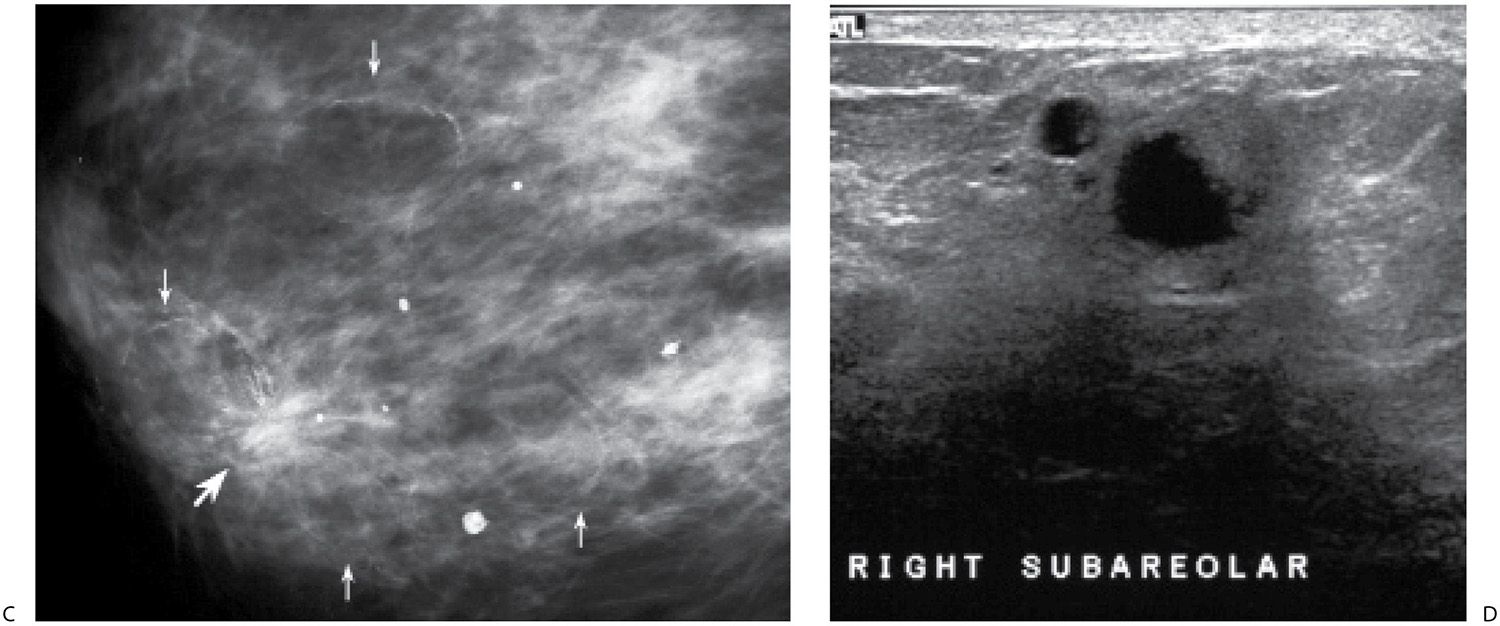

FIG. 9.7 • Trauma. A: CC views. A predominantly fatty pattern is present. Other than scattered dense, coarse dystrophic-type calcifications in the right breast, no abnormalities are identified. B: CC views 13 months following a motor vehicle accident with air bag deployment. As compared with the prior study, the right breast is smaller, and the trabecular markings are diffusely increased. C: Image photographically coned to the anterior aspect of the right breast. Distortion (large arrow) and oil cysts (small arrows), some with mural calcifications, are readily apparent, which, in conjunction with the diffuse changes, should suggest the likelihood of trauma. The job of the interpreting radiologist is to make all of the observations, postulate possible theories for the findings, and, in conjunction with a physical examination, review the patient’s pertinent history. In this patient, it is important to specifically ask about trauma. The patient may not associate the changes with an event that happened more than 1 year ago. D: Representative ultrasound image demonstrating disruption of normal tissue planes, minimally increased tissue echogenicity, and complex cystic and solid masses some with shadowing correlating with oil cysts seen mammographically.

Histologically, granulomatous mastitis is characterized by noncaseating granulomas limited to the perilobular regions; no microorganisms are identified in the tissue (7,8,11). It is a diagnosis of exclusion since granulomatous disease in the breast may also be reported in patients with sarcoid, Wegener granulomatosis, tuberculosis, diabetes, or connective tissue disorders. The treatment of patients with granulomatous mastitis remains controversial and not always effective. Some advocate the use of steroids after the possibility of an underlying bacterial etiology has been eliminated, while others have reported using methotrexate. Surgery alone has also been used with mixed results in that the disease may recur. A combination of steroids and surgery may be a more appropriate approach (13).

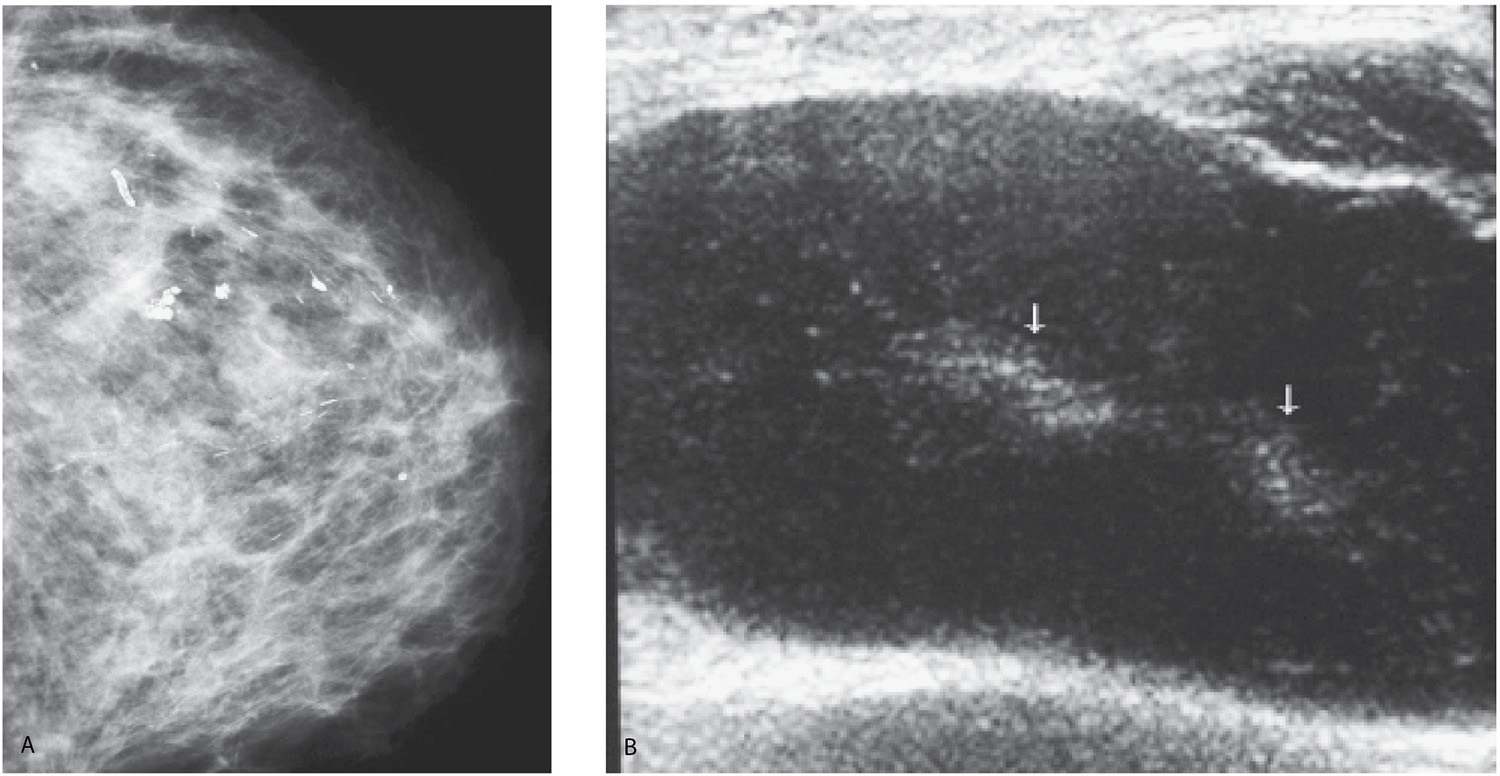

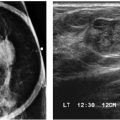

FIG. 9.8 • Acute bacterial mastitis. A: Right (kVp = 26, mAs = 68, compression = 4 cm) and left CC views (kVp = 34, mAs = 143, compression = 7 cm) in a patient with diabetes presenting with rapid onset of breast pain on the left with swelling and redness. The left breast is less compressible than the right, and the density of the breast is increased; both of these may in part be related to the patient’s inability to tolerate compression. As kV is increased to obtain an adequate exposure on the left, contrast decreases. B: Ultrasound. Skin thickening with loss of the echogenic deep dermal layer and dilated lymphatic channels (arrows) are seen throughout all four quadrants. The echogenicity of the tissue is increased with loss of normal soft tissue planes, likely reflecting edematous changes. Pus is obtained during surgical excision and drainage. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

FIG. 9.9 • Acute bacterial mastitis. A: CC views in a patient presenting with a rapid onset of right breast pain, swelling, and redness extending into the axilla and midaxillary line. The trabecular makings are increased laterally in the right breast extending to the edge of the film. B: Ultrasound. Loss of normal soft tissue planes and increased tissue echogenicity is noted in the lateral central aspect of the breast with extension of the parenchymal process to the midaxillary line along the 9 o’clock axis. In addition to the increased echogenicity of the tissue at this site, a localized irregular pocket of fluid is seen in the subcutaneous tissue with associated skin thickening. The patient is successfully managed with intravenous and subsequently oral antibiotics.

FIG. 9.10 • Granulomatous mastitis. A: MLO views in a 52-year-old patient who presents describing swelling and hardness of her right breast for 1 month with some resolution of the tenderness and erythema following a trial of antibiotics. Screening mammogram 8 months previously is normal. The right breast is less compressible and appears smaller than the left. The overall density of the right breast is increased compared with that of the left with higher technical factors (kVp and mAs) needed for an exposure on the right compared with the left. The patient is diagnosed with granulomatous mastitis following core biopsy and surgical excision. B: Ultrasound. The breast is diffusely abnormal with disruption of normal tissue planes, areas of hyperechogenicity, and tubular, serpiginous hypoechoic structures. C: Right MLO view obtained 5 months following views shown in A. The breast is normal in appearance with technical factors comparable to those used for exposures of the left breast. After the surgical resection, symptoms resolved. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

Arteritis

Giant cell or temporal arteritis is another rare cause of diffuse changes in the breast (Fig. 9.11). It may be a uni- or bilateral process, and biopsies usually demonstrate granulomatous inflammatory changes surrounding the arteries (7). This is a systemic panarteritis involving medium- and large-sized vessels in patients over the age of 50. The temporal arteries and other extracranial branches of the carotid artery are usually involved. Patients present with headaches, scalp tenderness, visual symptoms, jaw claudication, throat pain, and asymmetry of arm pulses. If blindness occurs, it is often irreversible. Patients have an elevated sedimentation rate with a normal white blood cell count, and approximately 50% have associated polymyalgia rheumatica. Elevated doses of prednisone are used in the treatment of symptoms and are helpful in minimizing visual disturbances.

FIG. 9.11 • Prominent vasculitis consistent with giant cell arteritis. CC views in a 70-year-old patient with diffuse left breast tenderness and swelling. Left breast appears larger than right. Diffuse prominence of the trabecular markings noted involving the left breast. Diagnosis made on excisional biopsy. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

Inflammatory Breast Cancer and Locally Advanced Breast Cancer

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) is characterized by a distinct clinicopathological presentation (14). It needs to be distinguished from locally advanced (neglected) breast cancer that, late in the course of the disease, can mimic some of the clinical findings described for IBC (15).

IBC is an uncommon, aggressive form of breast cancer that constitutes approximately 1% of all breast cancers; it is a stage IIIB cancer at the time of presentation. The diagnosis of inflammatory carcinoma is made on the basis of clinical findings (14). Unlike patients with locally advanced breast cancer in whom signs and symptoms may have been present for 6 months or more, patients with IBC describe the rapid onset of breast warmth, erythema involving at least one-third of the breast, and edema (14–16). As implied by its name, inflammatory carcinoma simulates mastitis in its presentation; however, the involved breast is not usually as tender as that seen in women with a diffuse acute bacterial mastitis. Although patients with inflammatory carcinoma may improve initially on antibiotics, the symptoms persist and eventually worsen.

Histologically, inflammatory carcinomas are usually poorly differentiated invasive ductal carcinomas characterized by tumor emboli in dilated dermal lymphatics and a lymphocytic reaction surrounding dilated vasculature in the dermis. These histological findings are found in approximately 80% of the patients with the clinical diagnosis of inflammatory carcinoma. The histological findings associated with inflammatory carcinoma are found in approximately 4% of patients who do not have the described clinical findings (7,8); the histologic finding of tumor emboli in dilated subdermal lymphatics in the absence of clinical signs and symptoms of IBC should not be used to diagnose patients with IBC (e.g., the diagnosis of IBC is made clinically).

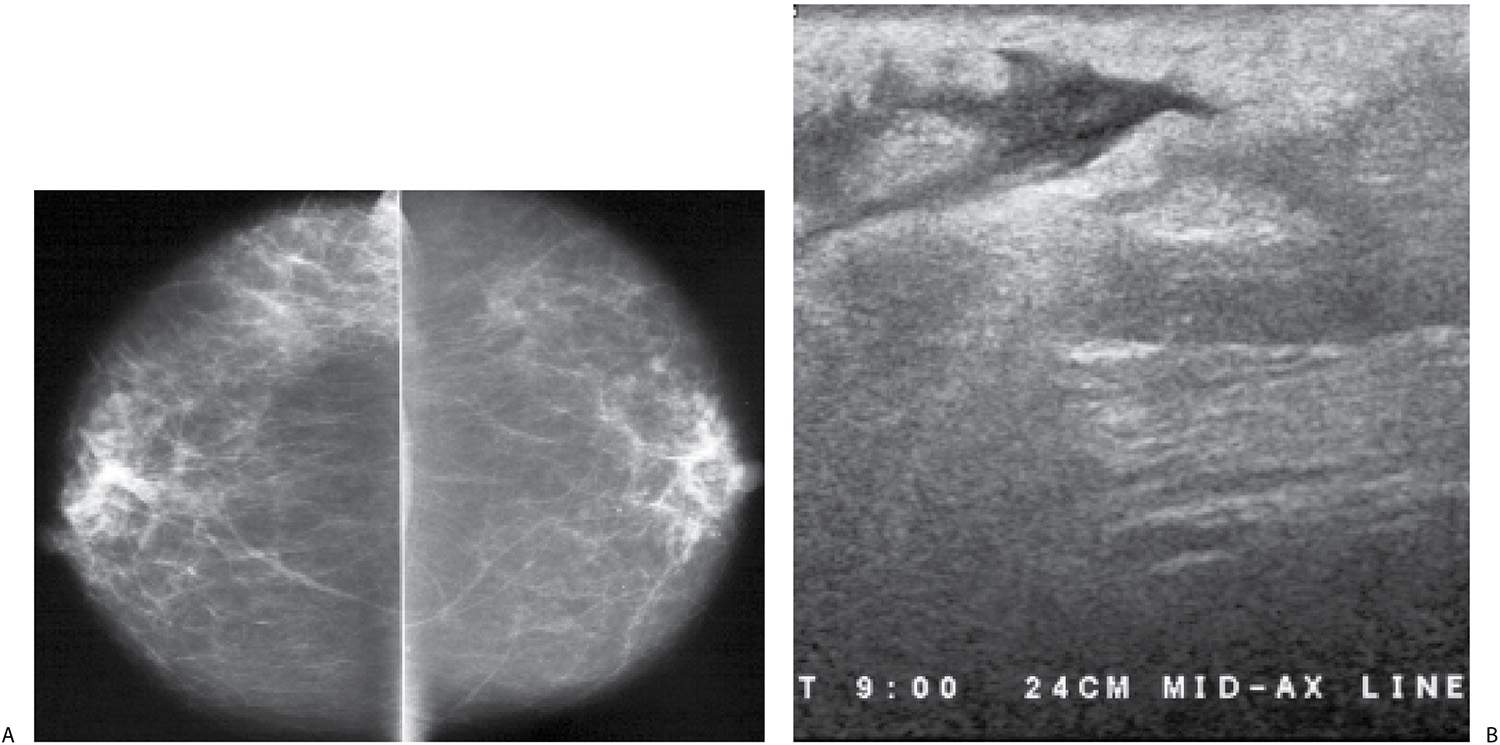

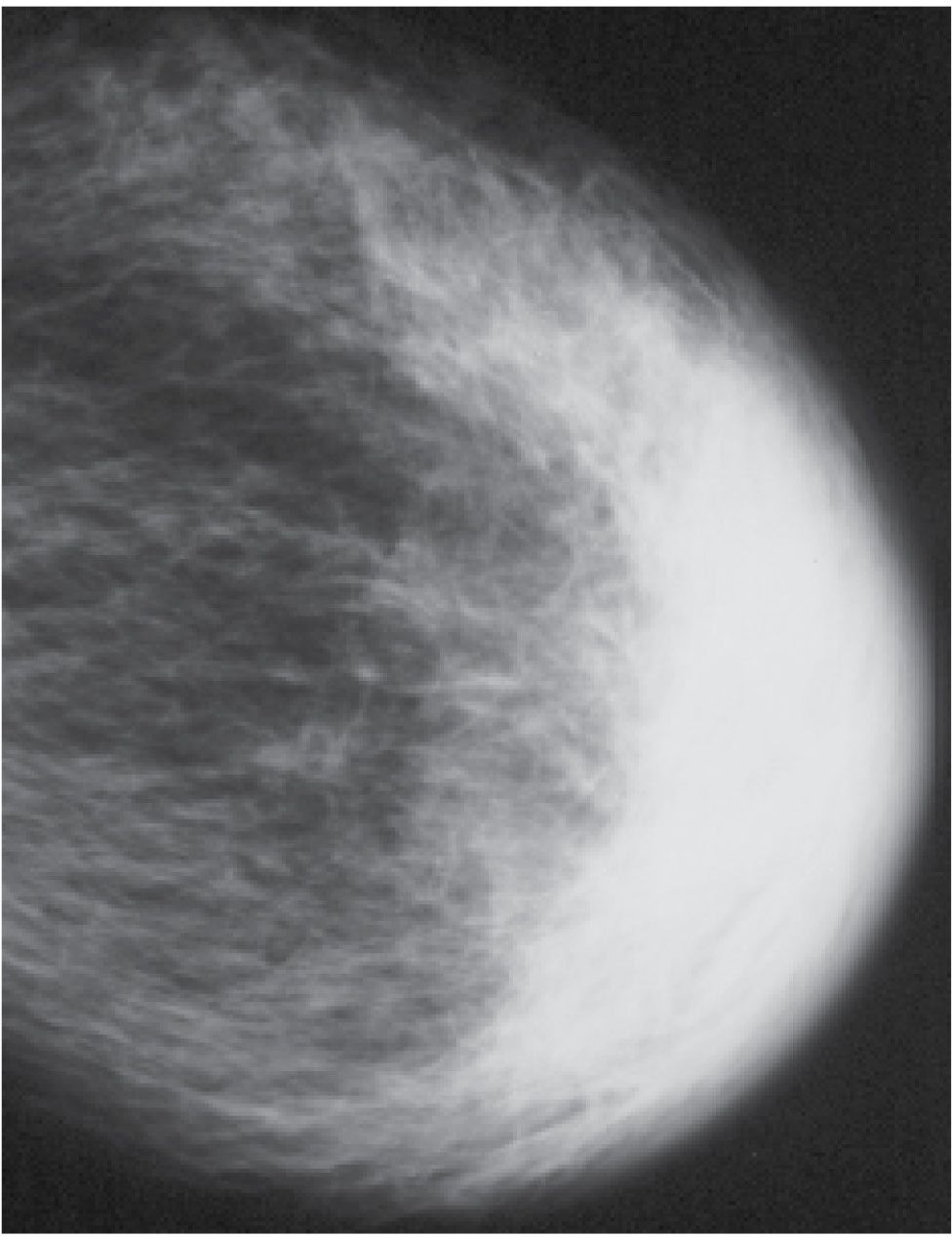

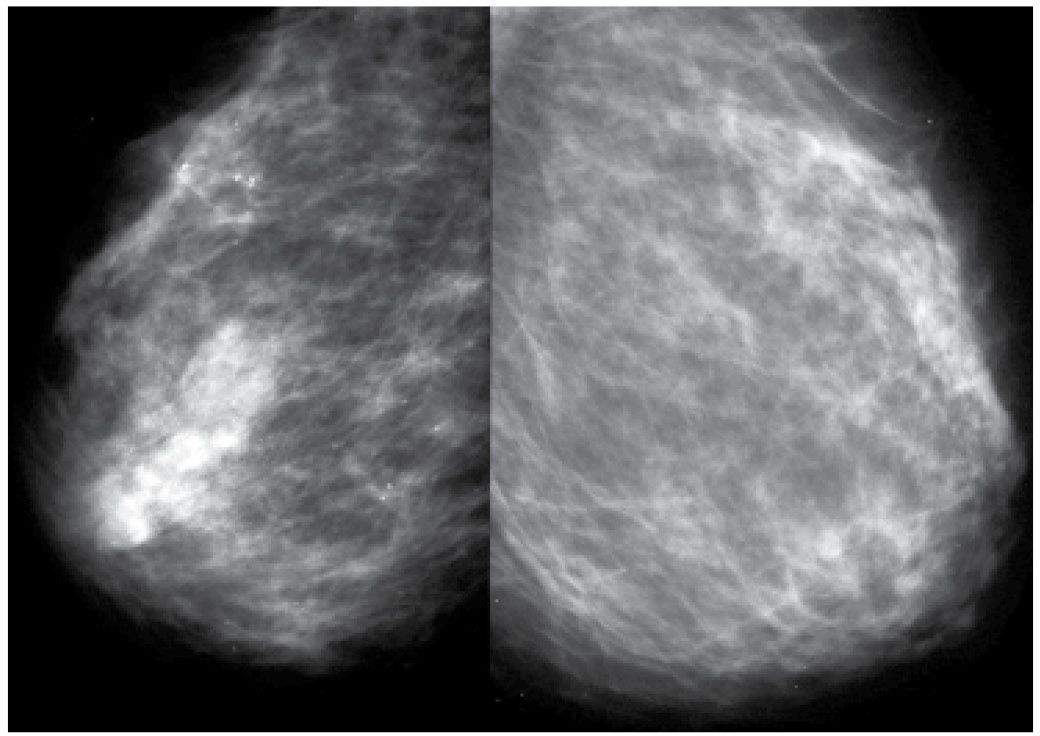

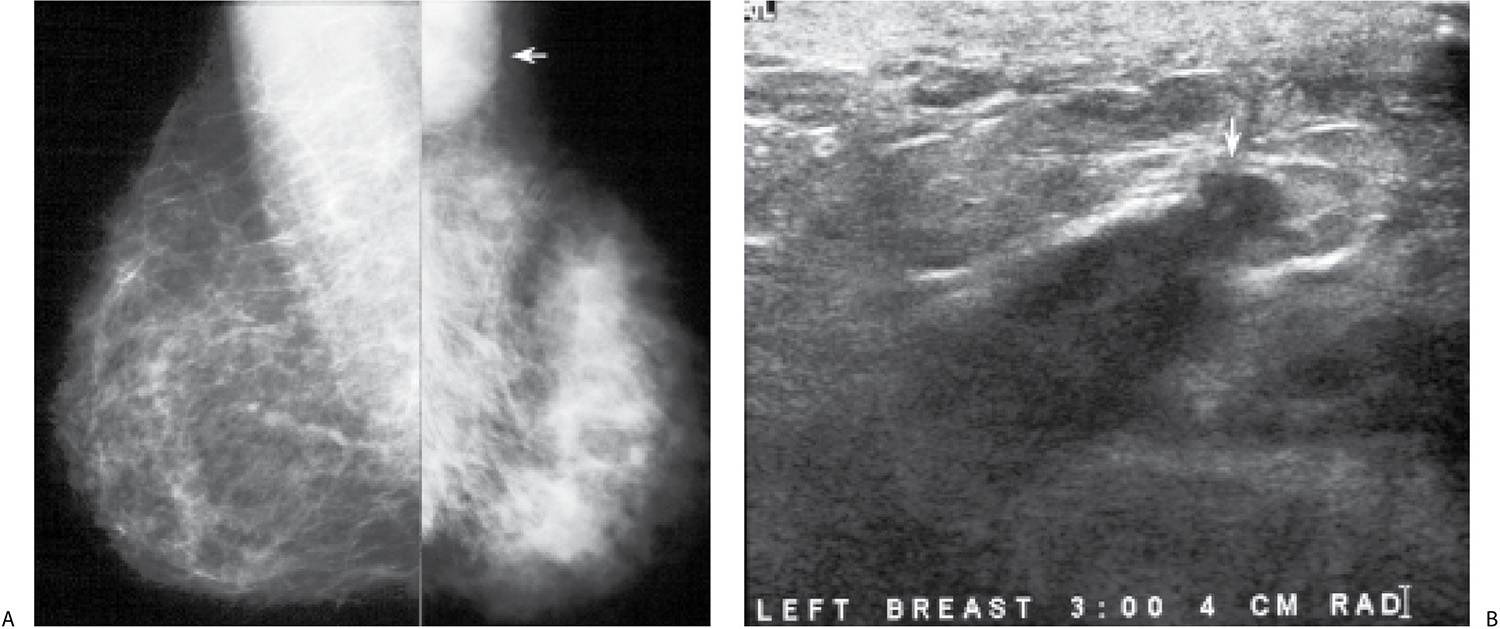

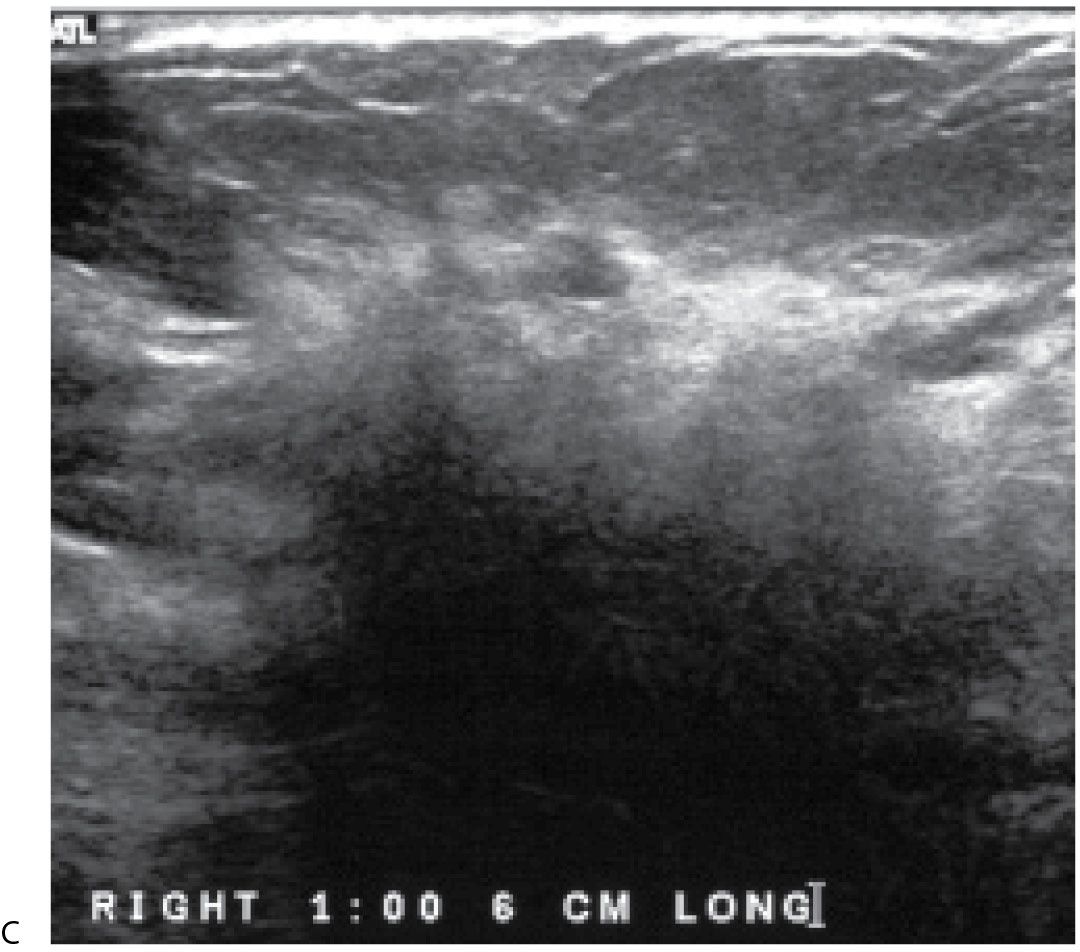

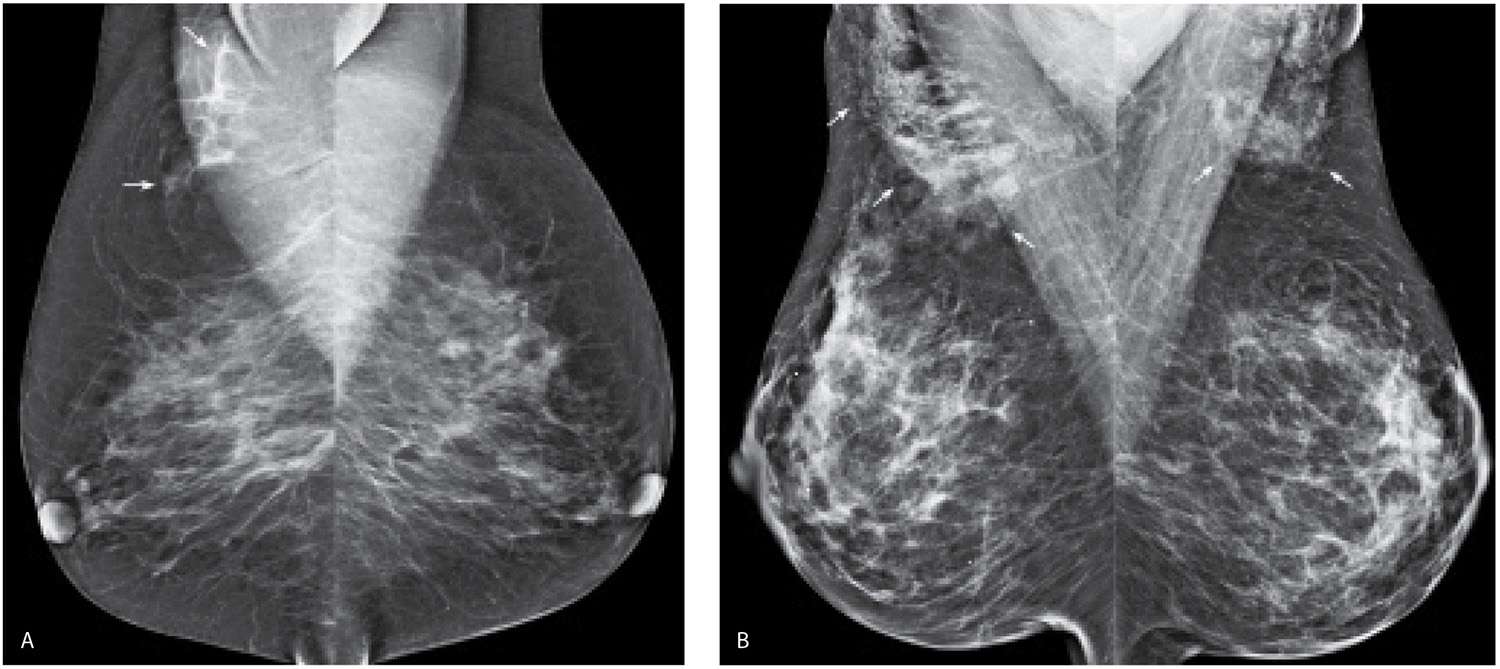

The affected breast is commonly larger and less compressible than the normal breast such that adequate exposure may be difficult to obtain (cm of compression, kVp, and mAs are higher than those used on the contralateral breast) in some patients. Increased breast size, skin thickening, and diffuse increases in the density of the parenchyma are the most common findings (Fig. 9.12) on mammography. Localized findings including a mass, architectural distortion, calcifications, and focal or global asymmetry may be identified in as many as 80% of patients (17–19). On the mammogram, axillary adenopathy has been reported in as many as 58% of patients at the time of presentation. On ultrasound, skin thickening, dilated lymphatics, disruption of normal breast architecture, and increased tissue echogenicity are commonly seen (17–19). In some patients, a focal finding including a mass, distortion, or calcifications may be detected. Ultrasound is also useful in the evaluation of the axilla with abnormal nodes reportedly detected in as many as 93% of patients with IBC (Fig. 9.13). If the appropriate areas are scanned with ultrasound, internal mammary as well as infra- and supraclavicular adenopathy may be detected with ultrasound in as many as 50% of patients (17). As mentioned previously, it is imperative that an effort be made clinically to distinguish patients with IBC from those that may have a locally advanced breast cancer with secondary skin involvement (18) (Figs. 9.14 through 9.16). If signs and symptoms are long-standing (>6 months), and no increased warmth, erythema, and peau d’orange changes (or if only one of these is present) are noted involving the affected breast, it is more appropriate to consider the diagnosis of a locally advanced breast cancer and not inflammatory carcinoma.

FIG. 9.12 • Inflammatory carcinoma. MLO views photographically coned to the anterior aspect of the breasts in a 49-year-old patient presenting with the rapid onset of erythema and edema involving the right breast; minimal tenderness (technique used for right MLO: kVp = 30, mAs = 295, compression = 8.1 cm; technique used for left MLO: kVp = 29, mAs = 122, compression = 6.4 cm). The compressibility of the right breast is decreased, and it appears smaller than the left. Increased density, thickening of the trabecular pattern and skin (seen with bright light) is apparent. Enlarged and dense axillary lymph nodes (not shown) are identified in the axilla on the right MLO view. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

Magnetic resonance imaging is particularly helpful in identifying a primary breast lesion as well as multifocal and –centric disease in patients with IBC. The affected breast is larger, and may be deformed with diffuse skin thickening and enhancement in more than 95% of all patients. Regional and internal mammary adenopathy can be identified as well as chest wall and pectoral muscle involvement. The detection of an underlying breast lesion is best done with MRI and ultrasound in 100% and 95% of patients, respectively (17). Mammography is reportedly the least sensitive with primary breast lesions being detected in 80% of patients (17).

Patients with IBC are treated aggressively with neoadjuvant chemotherapy for systemic disease followed by surgery and radiation therapy for local control. With anthracycline-based regimes followed by local therapy, 5- and 10-year survival rates of 40% and 33%, respectively, have been reported. The addition of taxanes is associated with higher survival rates as well as higher complete pathological responses (cPR) at the time of mastectomy. In patients with HER2/neu-positive tumors, treatment for 1 year with trastuzumab reportedly increases the likelihood of cPR and disease-free survival (20). After neoadjuvant therapy, a modified radical mastectomy with a full axillary dissection is the preferred surgical approach since SLN biopsy is reportedly not reliable in patients with IBC. Given the high incidence of local regional recurrence following adjuvant therapy and surgery, radiation therapy that encompasses the supraclavicular and internal mammary lymph node chains is recommended.

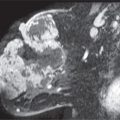

FIG. 9.13 • Inflammatory carcinoma. A: MLO views. The patient presents describing the rapid onset of redness, skin changes, and heaviness of the left breast. The left breast appears smaller with diffusely increased density and trabecular markings (Kerley B lines overlying pectoral muscle). A mass is also apparent in the left axilla (arrow). B: Ultrasound, left breast. On physical examination, the left breast is thicker and warmer than the right with diffuse erythema and peau d’orange changes. The skin also appears stretched and glistens. As the left breast is scanned, normal tissue planes are not apparent, and skin thickening is noted. An irregular mass (arrow) is identified laterally, and enlarged lymph nodes are imaged (not shown) in the axilla. Core biopsies of the mass and one of the axillary lymph nodes are done. Invasive ductal carcinoma, high nuclear grade with metastatic disease to a left axillary lymph node is reported. C: CT scan image. Axillary adenopathy (thick arrow), diffuse skin thickening involving the left breast and collateral vessels (thin arrows) medially in the area of the cleavage are imaged at this position. D: CT scan image. Left breast is thicker and firmer with diffuse skin thickening. At this level, an abnormal internal mammary lymph node (arrow) is apparent on the left.

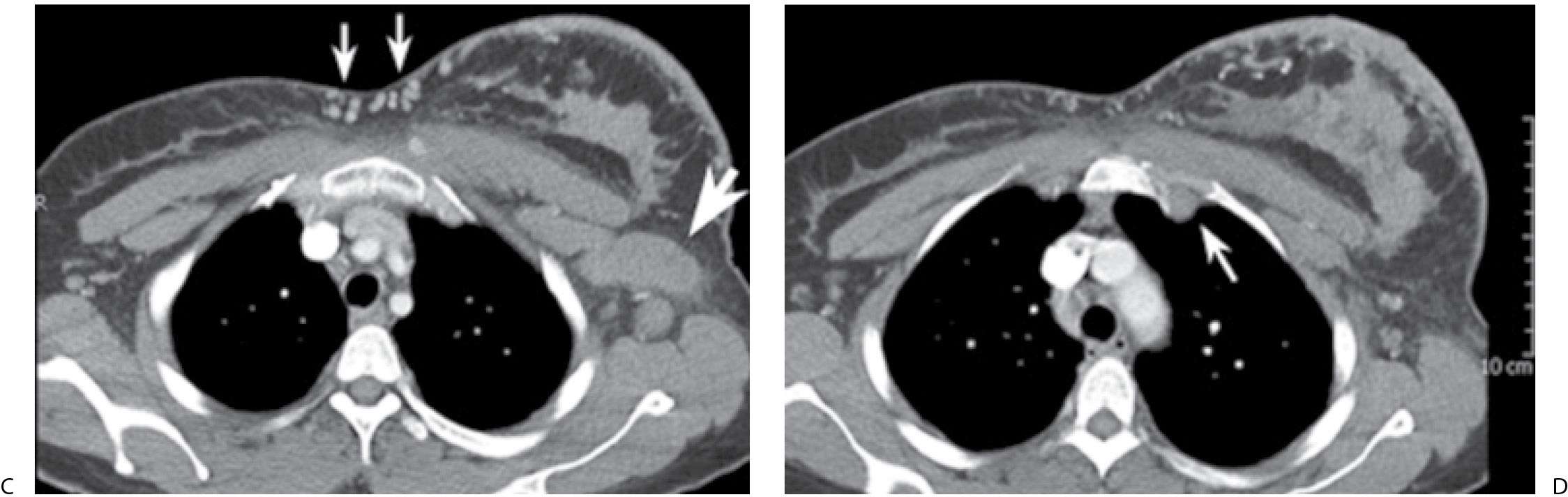

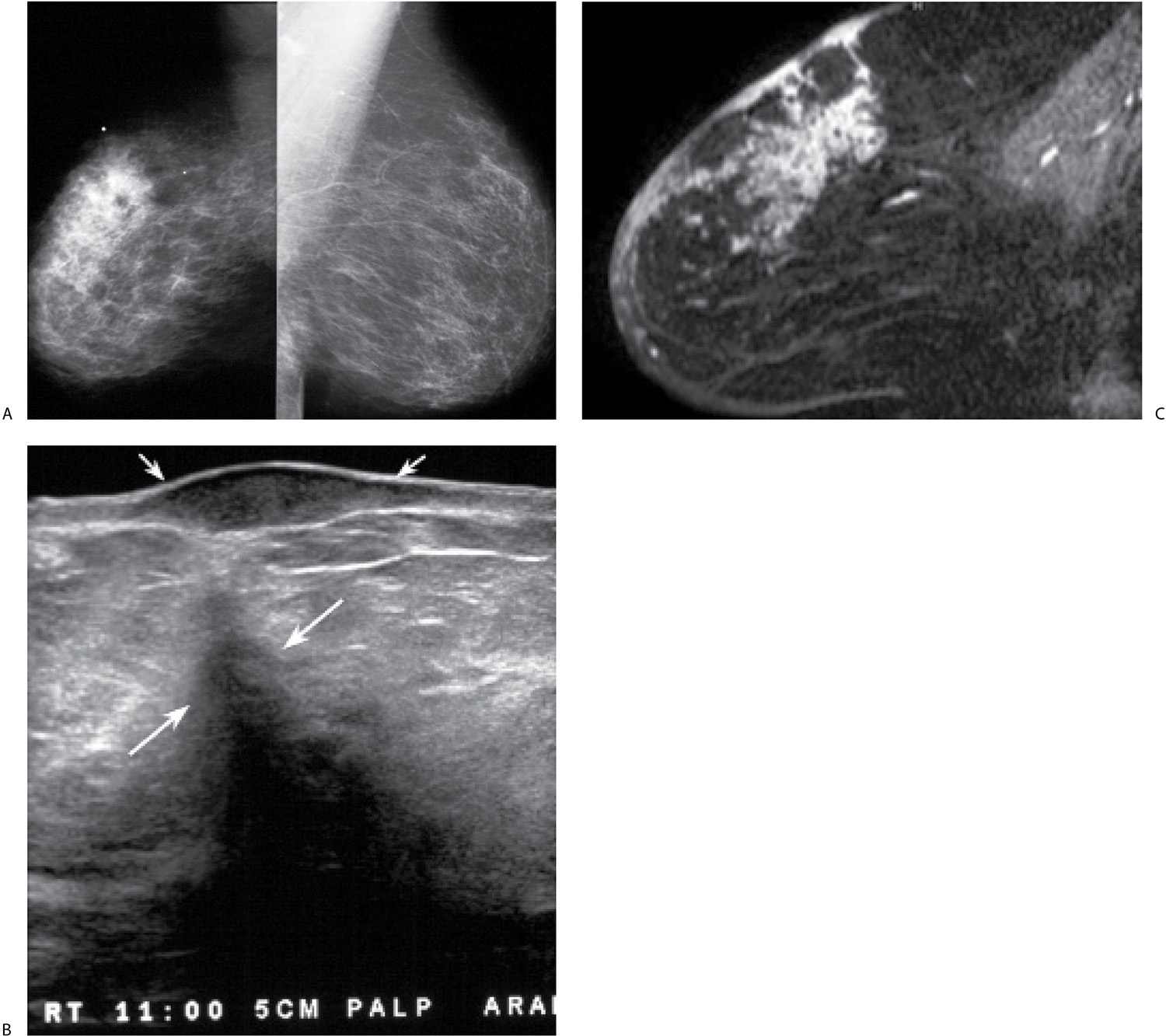

FIG. 9.14 • Locally advanced invasive ductal carcinoma with skin involvement. A: MLO views in a 76-year-old patient describing a “lump” in the right breast. Metallic BB denotes site of palpable finding. The right breast is smaller than the left with diffuse prominence of the trabecular markings and increased density localized to the superior aspect of the breast possibly corresponding to the palpable finding. B: Ultrasound image at site of “lump” demonstrates a hypoechoic mass in the dermal layer (small arrows) and an irregular mass (long arrows) with shadowing in the breast. Also note that normal soft tissue planes are not apparent, and the overall echogenicity of the tissue surrounding the mass is increased. This area is diffusely abnormal. C: MRI, sagittal T1-weighted reconstruction of the right breast post contrast. Non–mass-like regionally distributed heterogeneous enhancement is present superiorly associated with multiple sites of skin thickening and enhancement consistent with skin involvement; on sagittal T2-weighted fat-suppressed images (not shown), the skin masses are low in signal, and subcutaneous edema is present extending to the pectoral fascia. The patient is diagnosed with an invasive ductal carcinoma, high nuclear grade with multiple sites of skin involvement and 27 of 27 positive lymph nodes. The tumor is estrogen/progesterone receptor-negative, HER2/neu-positive.

FIG. 9.15 • Locally advanced invasive ductal carcinoma. A: MLO views (technique used for right MLO: kVp = 25, mAs = 105, compression = 4.9 cm; technique used for left MLO: kVp = 32, mAs = 150, compression = 7.0 cm) in a 56-year-old patient. The left breast is larger and less compressible than the right. The overall density of the left breast is increased, and the contrast is decreased, a reflection of the higher kVp needed for exposure on the left compared with the right. On the MLO views, you can see increased density and prominence of the trabecular marking superimposed on the pectoral muscle as well as a mass (arrow) with indistinct margins in the axilla. Additionally, a possible mass with indistinct margins is noted in the upper inner quadrant of the left breast, zone B. Ultrasound images (not shown) confirm the presence of a round complex cystic and solid mass in the upper inner quadrant of the left breast and a macrolobulated mass with no identifiable fatty hilum in the left axilla. The patient is diagnosed with invasive ductal carcinoma with lobular features and metastatic disease to the axilla following ultrasound-guided core biopsies. The tumor is estrogen and progesterone receptor-negative, HER2/neu-positive. B: MRI, maximum intensity projection demonstrates multiple enhancing masses with spiculated margins in the left breast as well as abnormal and matted lymph nodes in the left axilla. Note asymmetrically increased vascular structures in the left breast. C: MRI, sagittal T2-weighted fat-suppressed image of the left breast. Skin thickening and diffuse edematous changes are noted, as are matted lymph nodes (arrows) with intermediate T2 signal in the left axilla. Following 4 months of neoadjuvant therapy, cPR and no metastatic disease to the axilla (0/5 LNs) are reported at the time of the mastectomy.

Recurrence After Breast-Conserving Therapy

Recurrences following breast-conserving therapy typically develop at the lumpectomy site. Rarely, patients can present with diffuse changes, including enlargement of the breast, skin thickening, increased density, and prominence of the trabecular markings (Fig. 9.17; also see Fig. 11.32). In some of these patients, the breast changes may be related to the development of axillary adenopathy and increased interstitial fluid in the breast.

Invasive Lobular Carcinoma

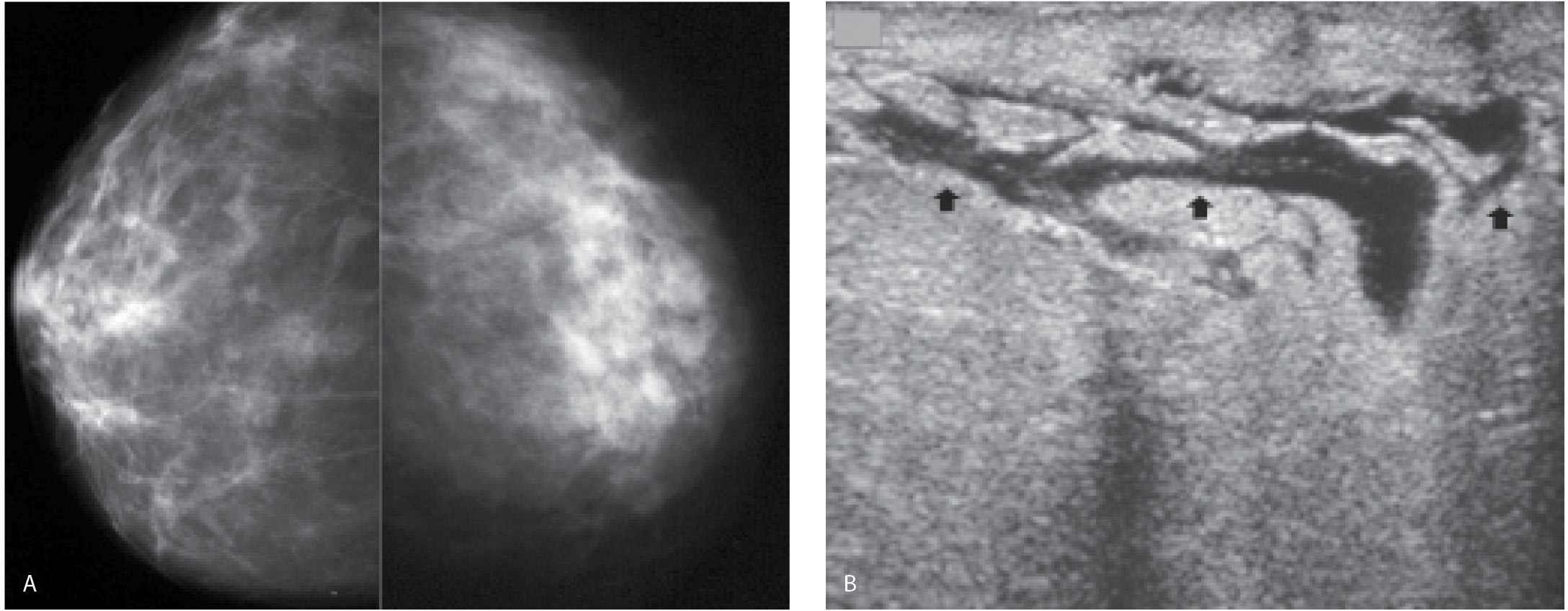

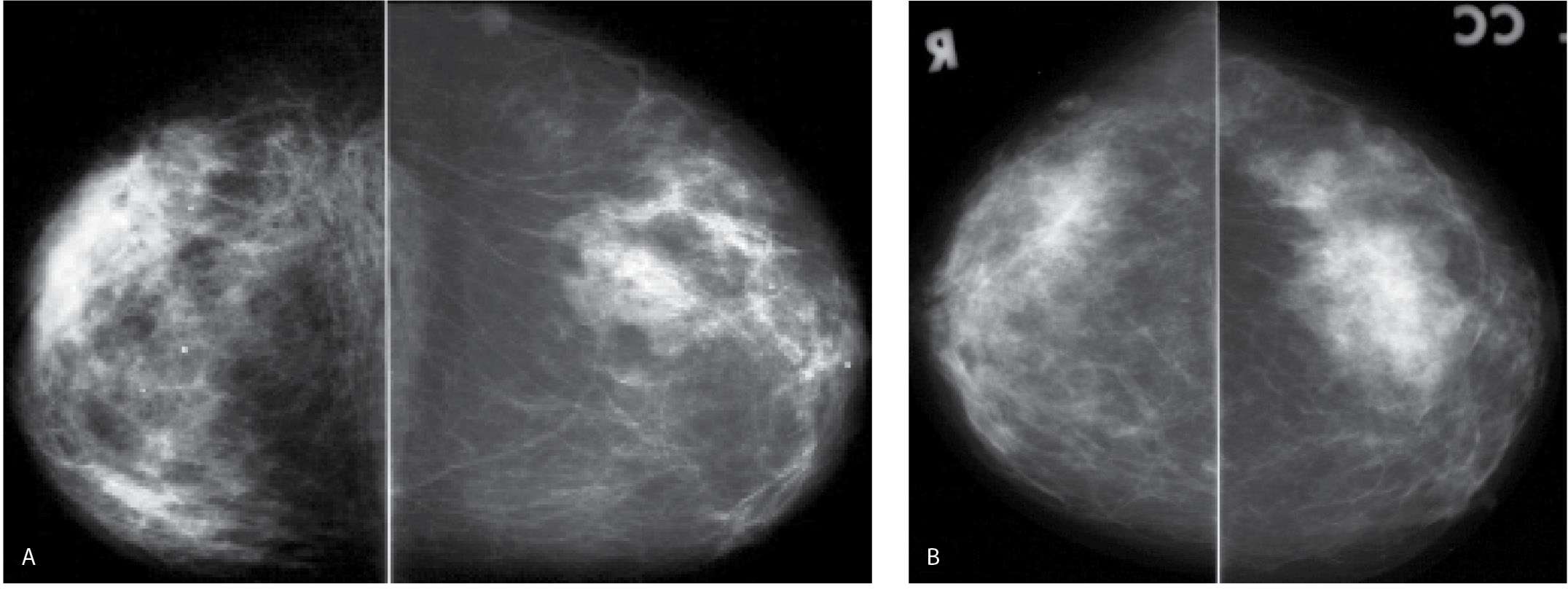

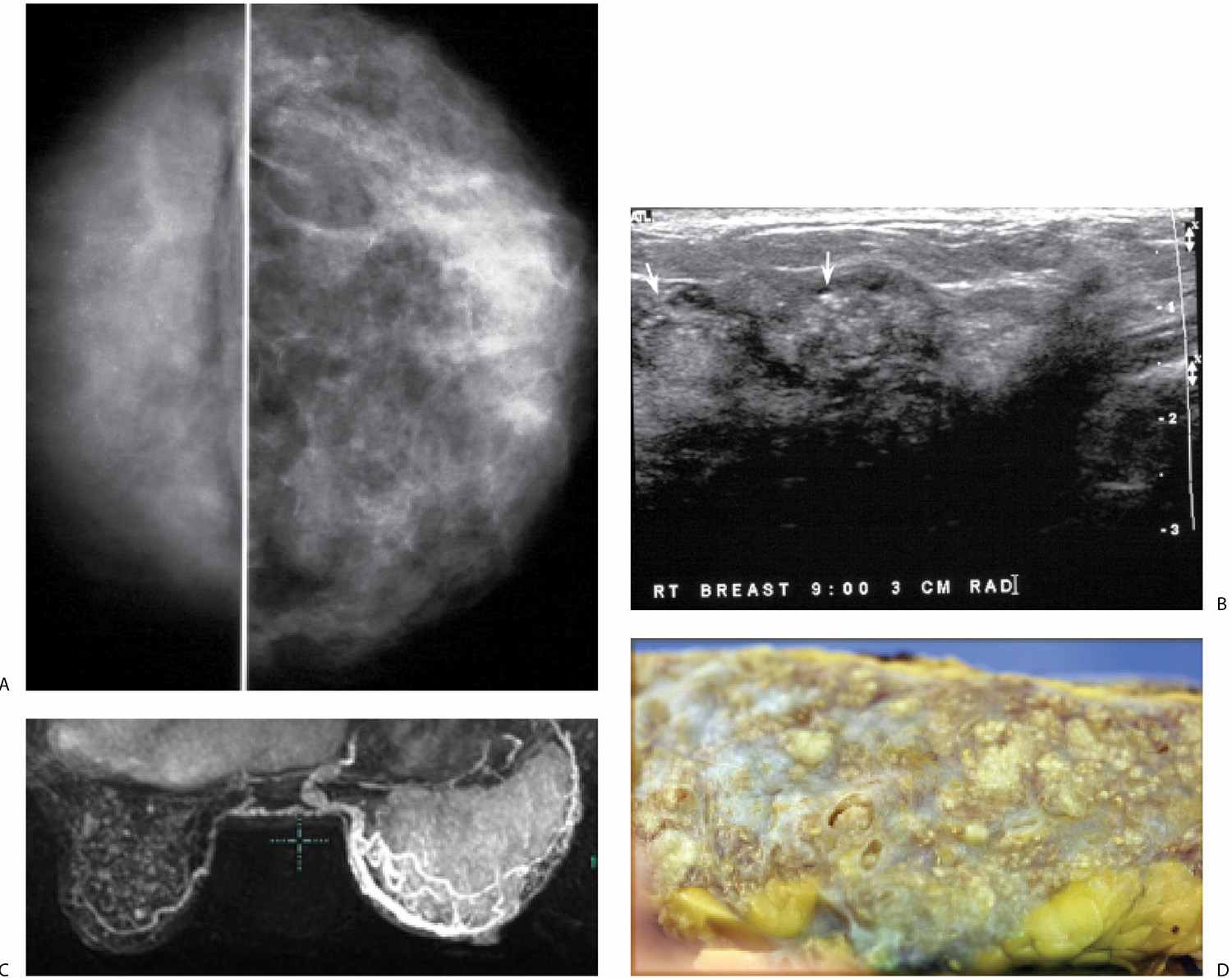

In addition to the more common localized presentations of invasive lobular carcinoma discussed in Chapter 8, patients may also have diffuse changes. The shrinking breast (Figs. 9.18 and 9.19), commonly reflecting invasive lobular carcinoma, is characterized by a progressive decrease in the size of the breast and an increasing prominence of the trabecular markings (21). On ultrasound, localized findings may be identified. This includes masses or an irregular, almost geometric abrupt interface between thickened echogenic tissue and intense shadowing (Figs. 9.18C and 9.19C). Enlarged, morphologically abnormal lymph nodes may be imaged in the axilla mammographically and on ultrasound. Asymmetric breast size, thickened skin, edematous changes, one or multiple enhancing masses or non–mass-like enhancement are more readily identified on MRI (Fig. 9.19D). MRI is also useful in the detection of regional adenopathy (axillary, infra/supraclavicular, and internal mammary). Less commonly, the involved breast may be enlarged, less compressible, and characterized by diffuse increases in breast density indistinguishable from the classic presentation of patients with IBC.

FIG. 9.16 • Locally advanced invasive ductal carcinoma. A: MLO views in a 47-year-old patient. The right breast is denser with a prominent diffuse “reticulonodular” pattern. If you are not actively thinking about diffuse changes, the finding may go undetected. An invasive ductal carcinoma high nuclear grade with metastatic disease to right axilla is diagnosed on ultrasound-guided cores biopsies (not shown). The tumor is estrogen and progesterone receptor-positive, HER2/neu-negative. B: MRI, maximum intensity projection demonstrating the extent of disease in the right breast. Foci of nonspecific enhancement are noted scattered in the left breast. C: MRI, T1-weighted sagittal reconstruction of the right breast image post contrast. Regionally distributed non–mass-like heterogeneous clumped and linear enhancement in the superior quadrants of the right breast. After neoadjuvant therapy, the MRI (not shown) demonstrates no focal abnormalities. A cPR with no metastatic disease to the axilla (0/12 LNs) is reported at the time of the mastectomy.

Ductal Carcinoma In Situ

The overwhelming number of patients with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is diagnosed following the detection of calcifications on screening mammography. A mass (palpable or screen-detected), nipple discharge, Paget disease of the nipple, diffuse changes in the breast, localized or more diffuse distension of a ductal system, and areas of parenchymal asymmetry that may or may not be associated with calcifications are less common presentations of DCIS. An increasing number of patients are diagnosed following the detection of segmentally distributed clumped and linear enhancement or an enhancing mass on MRI with no other clinical or imaging findings (please see Table 6.6).

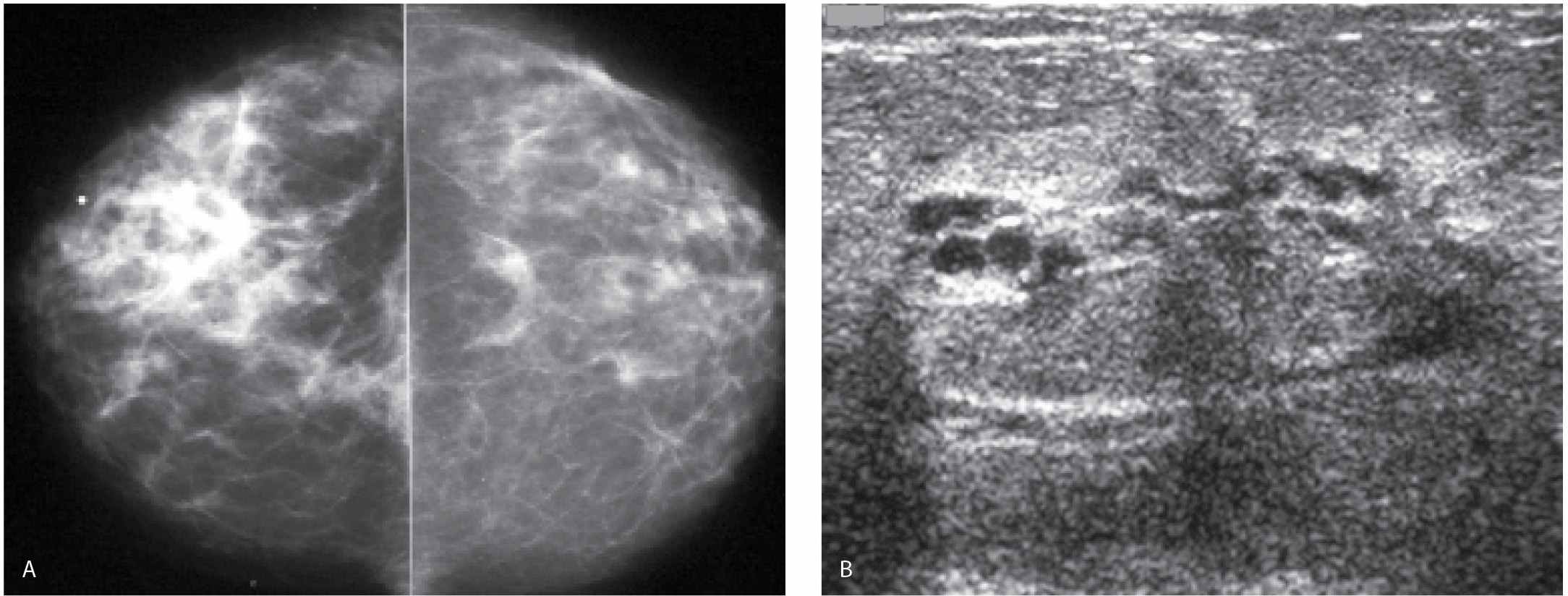

When DCIS presents as diffuse change, prominence of the trabecular markings may predominate (Fig. 9.20). Alternatively, asymmetry in the size and density of the involved breast with or without associated calcifications may be noted (Fig. 9.21; also see Fig. 5.38). On ultrasound, disruption of normal tissue architecture with irregular areas of hypoechogenicity, shadowing, calcifications (Fig. 9.21B), or dilated ducts (see Fig. 5.38) can be identified in some patients. An asymmetrically thickened breast with diffuse, non–mass-like enhancement (Fig. 9.21C) and edema may be seen on MRI; alternatively, segmentally distributed dilated ducts with surrounding enhancement on the postcontrast images may be noted (see Fig. 5.38). Although enlarged dense axillary lymph nodes may be found in these patients, these are reactive on core biopsy (e.g., metastatic disease in a patient with DCIS suggests unidentified invasive disease). In patients with diffuse changes, and a diagnosis of DCIS on core biopsies, an SLN biopsy should be considered at the time of the mastectomy. In the setting of diffuse DCIS, invasive disease may be identified in the mastectomy specimen, in which case the patient would need a full axillary dissection since SLN biopsy cannot be done after a mastectomy. It is also important to realize that invasive disease may be present but go undiagnosed since only representative sections from the mastectomy specimen are reviewed histologically.

FIG. 9.17 • Recurrent invasive ductal carcinoma. A: Left CC view. Two round dense masses are imaged in the lower inner quadrant of the left posteriorly. Invasive ductal carcinoma is diagnosed and treated with lumpectomy and radiation therapy. B: Left CC view done 7 years after image shown in part A. The density of the left breast is significantly increased compared with prior studies done following treatment (not shown). Diffuse prominence of the trabecular markings is now apparent as well as a new round dense mass in the upper outer quadrant of the left breast anteriorly. Bilateral mastectomies are done at this time. A year later, the patient presented with metastatic disease to the brain.

FIG. 9.18 • Invasive lobular carcinoma. Current MLO views in a 49-year-old patient (A) and MLO views for comparison, 3 years previously (B) . The right breast is now smaller (shrinking breast) than the left with diffuse prominence of the trabecular markings and an overall increase in the density of the parenchyma. A new oval dense mass (arrow in A) is seen superimposed on the right pectoral muscle. C: Ultrasound demonstrates an irregular mass with a thickened echogenic rim superficially, angular margins and intense shadowing distally in the upper inner quadrant of the right breast. Following ultrasound-guided core biopsies, the patient is diagnosed with invasive lobular carcinoma and metastatic disease to the axilla. Although she received neoadjuvant therapy, residual multifocal invasive lobular carcinoma (estrogen and progesterone receptor-positive, HER2/neu-negative) is found at the time of her mastectomy; sentinel lymph node biopsy (0/1 LN) is negative.

Lymphoma is primary to the breast when widespread or prior extramammary lymphoma is excluded (22). More commonly, lymphoma involves the breast secondarily. As discussed in Chapter 8, primary breast lymphoma may present with localized findings or with a more diffuse pattern of involvement (Fig. 9.22). Primary breast lymphomas are usually diffuse large B cell lymphomas (40% to 70%). Burkitt non-Hodkins lymphoma has been reported to involve the breasts of young, pregnant, or lactating women with an aggressive clinical behavior (7,8,22). Axillary and intramammary adenopathy are found in 30% to 40% of patients at the time of presentation (7,8).

PARENCHYMAL ASYMMETRY

In most women, breast tissue is symmetric. Rarely, women can have accessory tissue particularly in the axilla; this may be unilateral (Fig. 9.23A) or bilateral (Fig. 9.23B); this may be associated with accessory nipples. Although it may appear obvious, it is important to state at the onset that asymmetry cannot be established without the contralateral breast, and the term is used to describe “an area of fibroglandular-density tissue that is visible on only one projection, frequently representing superimposition of normal breast structures (summation artifact).” (23) Likewise, “developing parenchymal asymmetry” cannot be established in the absence of prior studies for comparison (Fig. 9.24). Parenchymal asymmetry may be characterized as “focal” when the island of tissue is localized, of similar size and density, and at approximately the same distance from the nipple in two or more projections (23,24). The tissue demonstrates intermingled fat and a gradual transition into the surrounding fat. The abrupt interface characteristic of a mass is not seen (Fig. 9.24). Asymmetry is characterized as “global” when the asymmetry involves larger aspects or entire quadrants of the breast (Fig. 9.25) (23,24). The progressive development of parenchymal asymmetry may reflect a benign process (hormonal, pseudoangiomatous stromal hyperplasia [PASH], focal fibrosis); however, it is viewed with more concern, and patients should be evaluated with spot compression views, correlative physical examination, and ultrasound; if the ultrasound is negative but concerns persist following the physical examination or spot compression views, a stereotactically guided biopsy can be done.

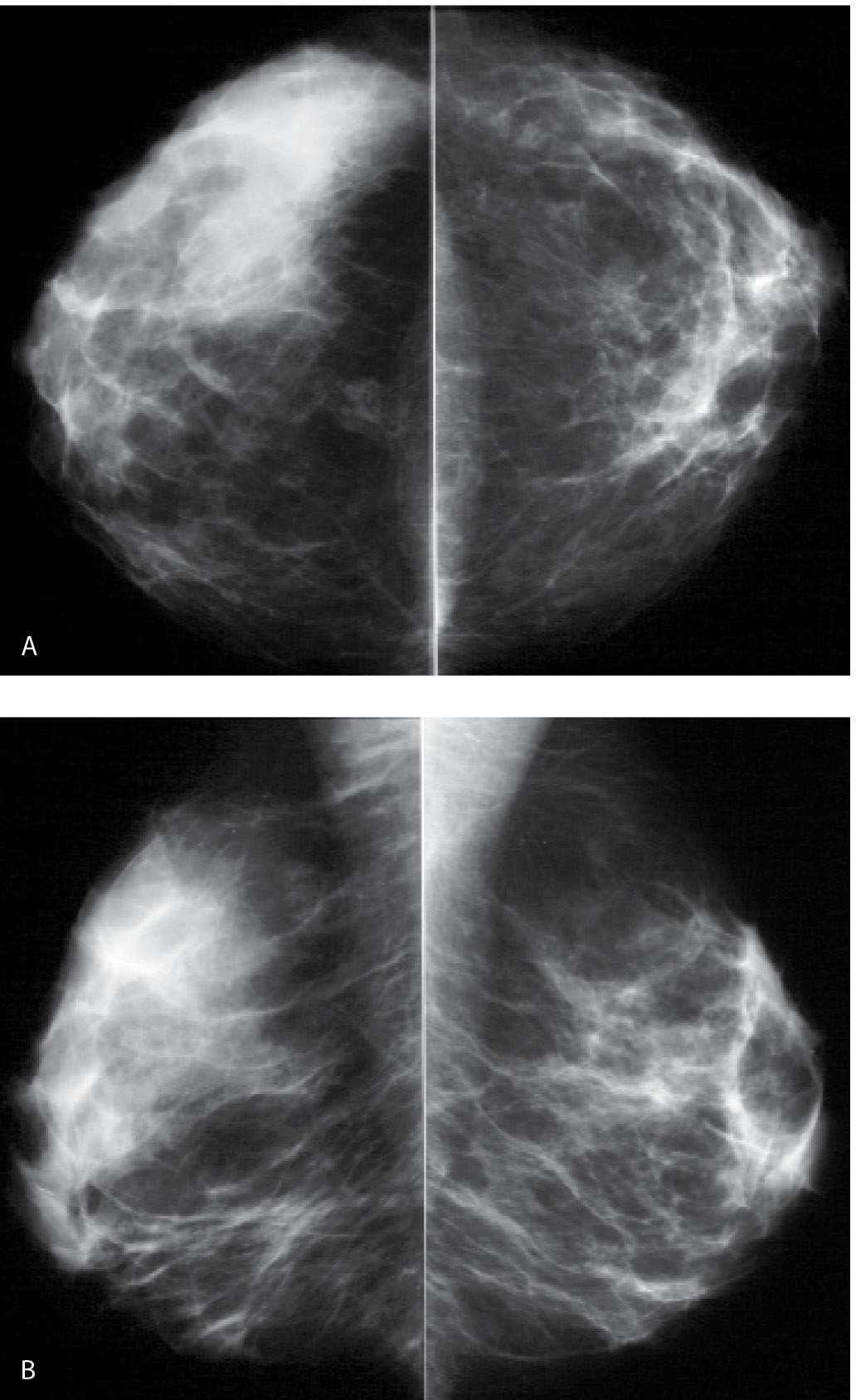

FIG. 9.19 • Invasive lobular carcinoma. A: Current CC views in a 65-year-old patient. B: CC views from 10 years before for comparison. The right breast is diffusely abnormal. It has decreased in size compared with the prior study and is smaller than the left breast. Diffuse prominence of the trabecular markings and an overall increase in the density of the breast is apparent. Also, incidentally noted is an increase in the amount of fat in the left breast with dispersal of the glandular tissue consistent with weight gain. C: Ultrasound. A vertically oriented mass with spiculated and angular margins as well as intense shadowing is imaged in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast. An invasive lobular carcinoma is diagnosed on core biopsy. The tumor is estrogen receptor-positive, progesterone receptor weakly positive and HER2/neu-negative. D: MRI, T1-weighted sagittal reconstruction of the right breast post contrast. Skin thickening is present. Although her known disease is in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast, multiple variably sized masses characterized by rapid wash in and wash out kinetic curves are identified predominantly, but not exclusively, in the lower quadrants of the right breast anteriorly. Skin thickening as well as subcutaneous and parenchymal edema extending to and along the pectoral fascia are apparent on T2-weighted fat-suppressed images (not shown).

Benign and malignant causes of parenchymal asymmetry are presented in Table 9.2. In many women, parenchymal asymmetry represents normal variation. It is also sometimes iatrogenic following excisional biopsy (see Fig. 11.4). Keep in mind, however, that on a single point in time, we have no way of knowing whether parenchymal asymmetry is stable or developing, and, as such, particularly in older women, evaluation is encouraged if there are no prior studies for comparison. Intervention is usually not warranted if there is no correlative physical finding and the ultrasound focused to the site of the asymmetry is normal. If the area of asymmetry is hard or indurated on physical examination, or if an abnormality is seen on ultrasound, biopsy may be indicated unless the history provides a good explanation for the findings. In addition to benign etiologies, malignant causes include invasive ductal (Fig. 9.26) and lobular carcinomas, DCIS (Fig. 9.27 and 9.28), in which case the parenchymal asymmetry may be associated with calcifications and lymphoma (Fig. 9.29).

PAGET DISEASE

Paget disease of the nipple represents 1% to 5% of all breast cancers with no reported age predilection (7,8). It is seen in less than 1% of men (7). Initial findings are limited to the nipple and include reddening with associated pruritus and pain. As the disease progresses, the nipple surface may be moist (oozing, gummy), there may be scaling, and eczematoid changes leading to ulceration, erosions (Fig. 9.30A), and crusting (Fig. 9.30B) of the nipple surface (25). It is usually a unilateral process associated with an underlying intraductal or invasive ductal carcinoma in as many as 95% of patients. In addition to the nipple changes, patients can present with a concurrent palpable abnormality; invasive ductal carcinoma is diagnosed in 75% to 90% of patients presenting with a palpable finding. The nipple findings may be all that is apparent in 40% of women with an underlying invasive ductal carcinoma or in many of those with an underlying DCIS. Although the associated malignancy is commonly found in the central, subareolar aspect of the breast, it is peripheral in as many as 35% to 40% of patients. The associated DCIS is usually high grade with central necrosis, and the invasive lesions are typically poorly differentiated invasive ductal carcinomas (25–29).

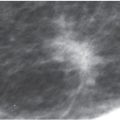

FIG. 9.20 • DCIS. MLO views in an 84-year-old patient. Diffuse prominence of trabecular markings is noted on the right. No malignant-type calcifications are identified. Multifocal DCIS, micropapillary, clinging and solid types are reported at the time of the mastectomy with no invasive disease identified.

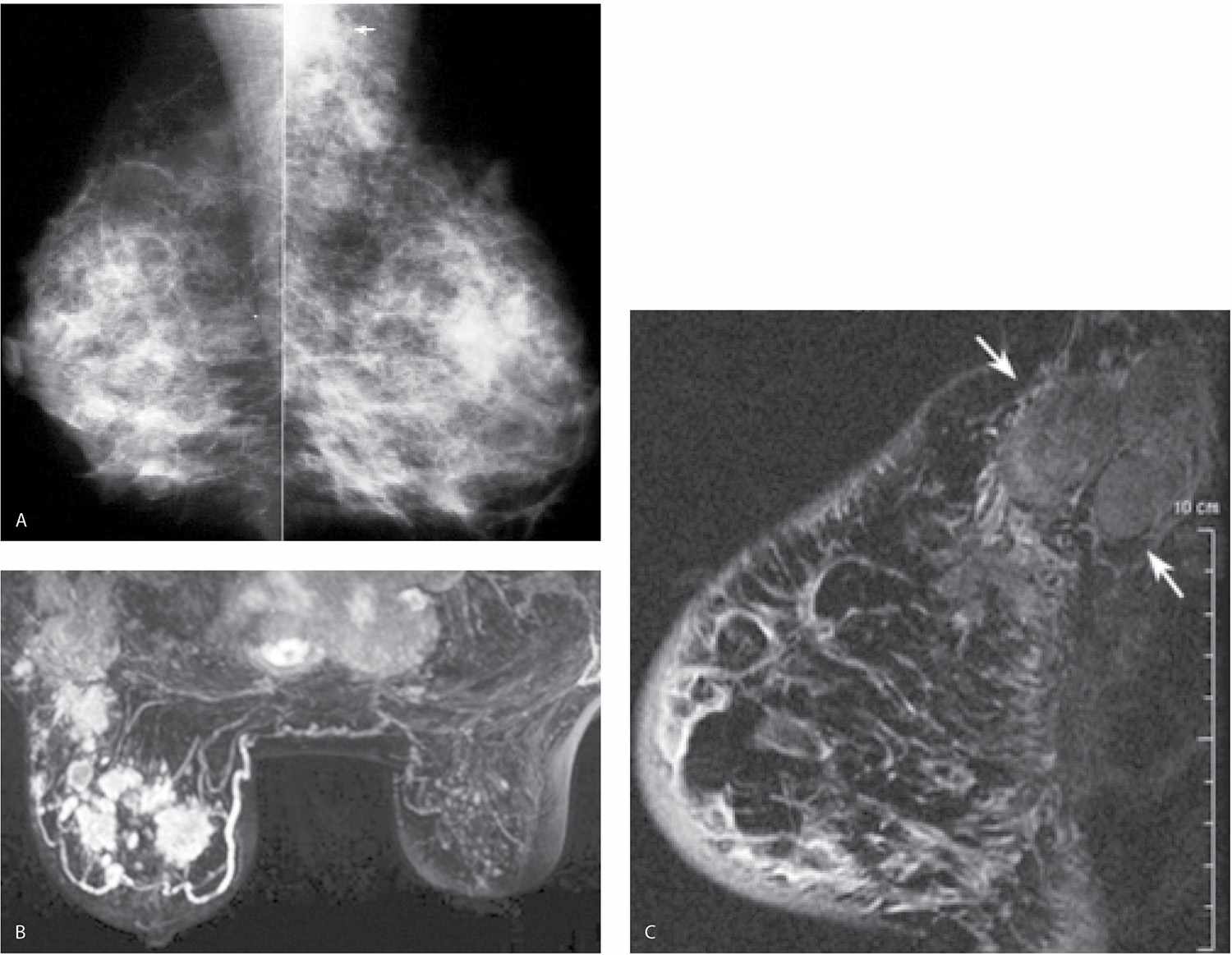

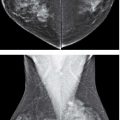

FIG. 9.21 • DCIS. A: CC views in a 45-year-old patient. The right breast is smaller. Fine pleomorphic calcifications are present diffusely scattered in asymmetrically dense breast parenchyma on the right. B: Representative ultrasound image demonstrates disruption of normal tissue architecture, distal shadowing, and rounded mass-like areas of tissue, some with numerous echogenic foci (arrows), reflecting the calcifications noted mammographically. C: MRI, maximum intensity projection. The right breast is thicker and on the MRI appears larger than the left. Diffuse enhancement and asymmetrically dilated venous structures are present. Foci of nonspecific enhancement are noted in the left breast. D: Gross image of the mastectomy specimen. Multiple variably sized ducts with intraluminal comedos are present. Diffuse, DCIS, high nuclear grade papillary and solid types with comedonecrosis and calcifications are described on the mastectomy specimen. Extensive sampling is done with no invasive disease identified. Sentinel lymph node biopsy (0/4 LNs) is negative.

In as many as 50% of patients, the mammogram is normal at the time of presentation. Alternatively, nipple retraction, nipple and areolar thickening, calcifications in the nipple and subareolar area, or a mass may be present (Fig. 9.30C). A mass or malignant-type calcifications as well as asymmetric tissue or distortion may be seen away from the subareolar area. Ultrasound may demonstrate an underlying hypoechoic mass; however, the findings may be nonspecific and include skin thickening, irregular areas of hypoechogenicity with disruption of normal tissue planes, and distended ducts that may demonstrate calcifications (26–29).

The high incidence of false-negative mammograms, in conjunction with the observation that even when there are mammographic findings, the extent of the disease is underestimated in as many as 43% of patients, has led to reports describing the use of MRI in patients presenting with Paget disease (28,29). In these patients, MRI can demonstrate clinically and mammographically occult malignancy as well as the extent of the disease (e.g., multifocal and multicentric disease) in the breast. MRI findings, alone or in combination, include intense nipple enhancement, thickening, and enhancement of the nipple areolar complex, clumped and linear enhancement, or one or more enhancing masses (Fig. 9.30D, E). Including MRI in the diagnostic evaluation of patients with Paget disease is particularly appropriate when the mammogram is negative and the patient is considering conservative therapy (28–30).

FIG. 9.22 • Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. A: Left CC view. Increased density and diffuse prominence of the trabecular markings are noted involving the left breast. Dystrophic and rod-like calcifications are scattered in the parenchyma. B: Ultrasound, left axilla. Enlarged lymph nodes are noted. The cortex is markedly hypoechoic and thickened, with mass effect and attenuation (arrows) of the central hyperechoic hilum. Posterior acoustic enhancement is noted. (From Cardeñosa G. Breast Imaging [The Core Curriculum Series]. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003.)

FIG. 9.23 • Accessory glandular tissue in the axilla. A: MLO views demonstrate asymmetric glandular tissue (arrows) superimposed on the right pectoral muscle, consistent with accessory glandular tissue in the axilla. Some women may have accessory nipples in the axillae or along the milk line extending bilaterally to the groin areas with variable amounts of associated glandular tissue. B: MLO views demonstrating accessory glandular tissue (arrows) bilaterally in the axilla, slightly more prominent on the right than the left. Some women with accessory glandular tissue in the axillae may present describing palpable findings with associated pain in the axillae that fluctuate with their cycles. On physical examination, prominent globular tissue is palpated, and normal tissue is imaged on ultrasound.

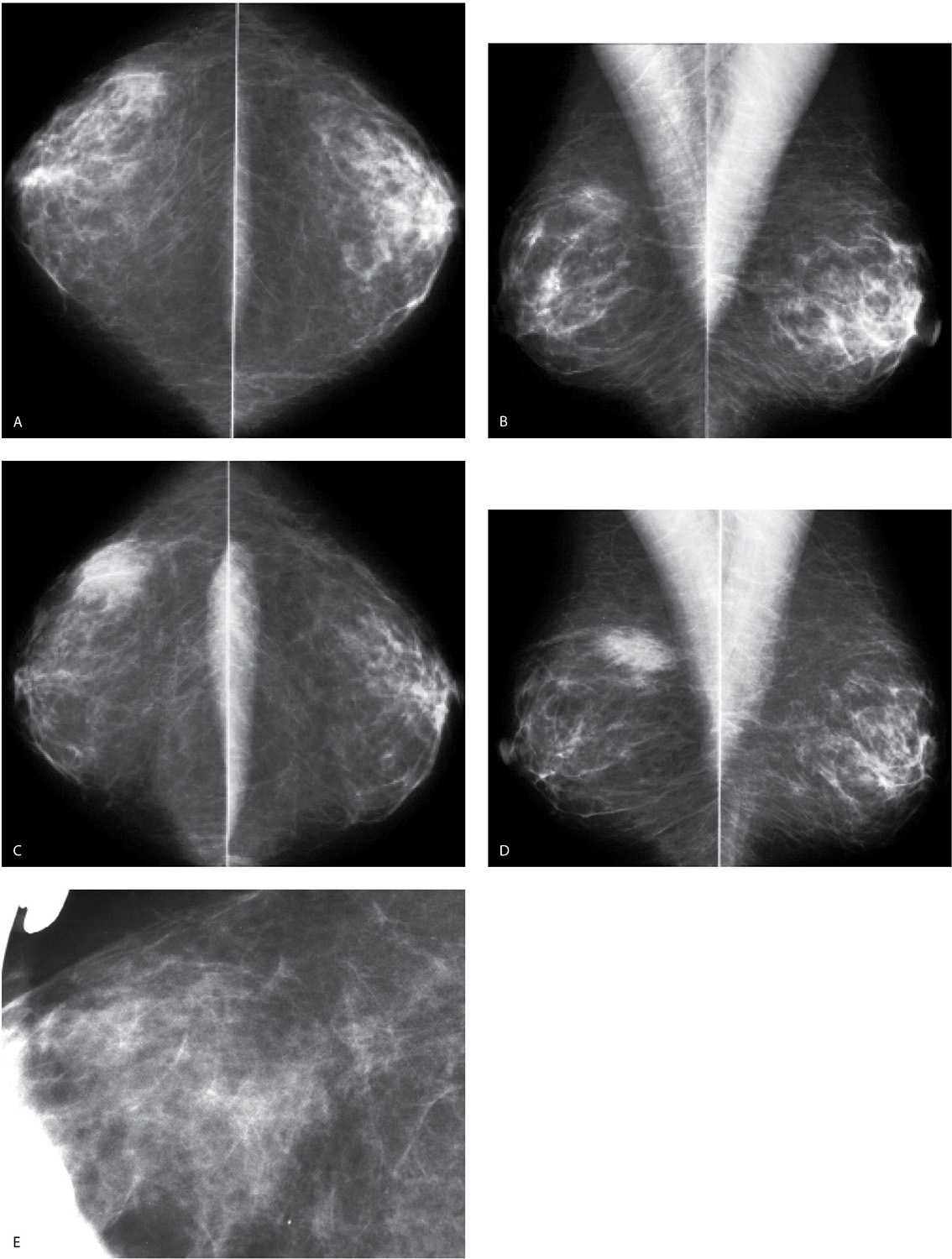

FIG. 9.24 • Developing focal parenchymal asymmetry. CC (A) and MLO (B) views. CC (C) and MLO (D) views, 1 year later in a 45-year-old woman. Developing asymmetry is identified in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast posteriorly. The finding correlates in size, density, and distance from the nipple on CC and MLO views. E: CC spot compression views. Fatty tissue intermingled with glandular tissue having a gradual transition into the surrounding tissue is seen on orthogonal spot compression views (only CC spot is shown). Normal tissue is palpated and imaged on ultrasound at the expected location of this finding. BI-RADS 2: Benign finding.

FIG. 9.25 • Global parenchymal asymmetry. CC (A) and MLO (B) views demonstrate asymmetric dense glandular tissue in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast. The tissue is scalloped, and a gradual transition is noted with the surrounding fatty tissue. BI-RADS 2: Benign finding.

Table 9.2 DIFFERENTIAL: PARENCHYMAL ASYMMETRY

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree