The female perineum has a complex anatomy and can be involved by a wide range of pathologies. In this article, we specifically focus on the clitoris, labia, and introitus. We discuss the normal anatomy of these structures, the MR imaging techniques to optimize their evaluation, and several common and uncommon entities that may affect them, including benign and malignant tumors, as well as infectious and inflammatory, vascular, iatrogenic, and developmental entities.

Key points

- •

A variety of common and uncommon pathologies affect the clitoris, labia, and introitus.

- •

These can be better evaluated by knowledge of the normal anatomy and optimized MR imaging techniques to facilitate observation of these entities.

- •

This is important to avoid unnecessary surgeries for benign conditions and to assist with surgical planning.

Introduction

MR imaging is an ideal technique to evaluate the female perineal structures owing to its excellent soft tissue contrast differentiation, high sensitivity to detect fluid, and multiplanar imaging capability. In this article, we specifically focus on the evaluation of the clitoris, labia, and introitus. We discuss the normal anatomy of these structures, techniques to optimize their MR imaging evaluation, and several common and uncommon entities that may affect them. Knowledge of these conditions can prevent unnecessary surgeries in benign entities and assist with preoperative planning when surgery is needed.

Introduction

MR imaging is an ideal technique to evaluate the female perineal structures owing to its excellent soft tissue contrast differentiation, high sensitivity to detect fluid, and multiplanar imaging capability. In this article, we specifically focus on the evaluation of the clitoris, labia, and introitus. We discuss the normal anatomy of these structures, techniques to optimize their MR imaging evaluation, and several common and uncommon entities that may affect them. Knowledge of these conditions can prevent unnecessary surgeries in benign entities and assist with preoperative planning when surgery is needed.

Normal anatomy

The female perineal anatomy is complex. The mons pubis is adipose tissue that overlies the pubic symphysis and separates inferiorly into thick skin folds, which are the labia majora, bilateral anterior structures at the medial borders of the thighs. The labia minora arise at the medial borders of the labia majora in the midline. The anterior borders of the labia minora fuse at the level of the clitoral glans, forming the clitoral dorsal hood or prepuce.

The clitoris is a pyramidal structure with the distal urethra and vagina as a core in the midline. It is deep to the labia minora and the bulbospongiosus and ischiocavernosus muscles. The clitoris and the perineal neurovascular bundles are large, paired terminations of the pudendal neurovascular bundles. The clitoris is composed of erectile tissue (paired crura, bulbs, and corpora) and a nonerectile tip (glans), as detailed below ( Fig. 1 ).

Crura

- •

Parallel and medial to the ischiopubic rami

- •

Each tapers posteriorly to a thin line that becomes continuous with the ischiocavernosus muscle (dark on MR imaging)

- •

Each continues anteriorly as the bodies (corpora)

- •

Bodies (Corpora)

- •

Formed by 2 corpora cavernosa within a fibrous envelope, separated by an incomplete septum

- •

Start posteriorly as the crura and join anteriorly as a single body

- •

Descends and folds back on itself in a “boomerang-like” shape (best seen on the sagittal view)

- •

Superior body is attached by the deep suspensory ligament to pubic symphysis undersurface

- •

Most caudal part is contiguous with the glans

- •

Bulbs

- •

Paramedian erectile tissue, parallel to the crura

- •

Surround urethra and vagina anterolaterally

- •

Convene anteriorly at the commissure, ventral to the urethra and close to the body and glans

- •

There may be point(s) of communication between commissure of the bulbs and the clitoral bodies

- •

Glans

- •

Nonerectile tissue

- •

Caudal end of the body

- •

Partly external

- •

Projects into the mons pubic fat

- •

Midline septum is evident

- •

The ischiocavernosus muscles cover the crura and attach to the ischiopubic rami, aiding in clitoral erection in combination with the bulbospongiosus mucles. There is no difference in clitoral morphology between premenopausal and postmenopausal women.

Optimized MR imaging techniques

In our practice, we place gauze between the labia for labial separation and better delineation of the clitoris and labia ( Fig. 2 ). Our perineal MR imaging protocol consists of the following sequences (slice thickness/field of view):

- •

Sagittal T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) (4 mm/22 mm)

- •

Axial oblique fat-saturated (FS) T2WI, perpendicular to abnormality (4 mm/22 mm)

- •

Coronal oblique T2WI, parallel to abnormality (4 mm/22 mm)

- •

Axial T1-weighted imaging (T1WI) in/out phase (5 mm/34 mm)

- •

Axial diffusion-weighted imaging (4 mm/22 mm)

- •

Axial oblique 3D T1WI FS precontrast (same angle and coverage as the axial oblique T2WI FS) (3 mm/24 mm)

- •

Axial oblique 3D T1WI FS post contrast—2 phases post timing run (3 mm/24 mm)

For imaging of the introitus, we administer 60 mL of ultrasound gel into the vagina via a Foley catheter and add an axial T2WI high-resolution sequence, which can be obliqued to cover the mass or region of interest only.

Clitoral anatomy is best seen in the axial plane with sagittal and coronal planes providing additional details, such that all components can be seen on MR imaging, with each plane providing a different representation of the structure. Sagittal planes demonstrate the angled “boomerang-shaped” clitoral body and glans at the undersurface of the pubic symphysis. The coronal plane demonstrates the 2 corpora uniting into a single body and terminating in the glans clitoris as well as depicting the labia minor and majora.

Applying fat saturation highlights the cavernous tissue owing to its increased vascularity. The clitoris enhances avidly on postcontrast T1WI, although the clitoral bulb enhances slightly less than the remainder of the clitoris. The labia minora enhance more than the labia majora.

Benign perineal tumors

An array of neoplasms can affect the perineal structures, posing a diagnostic challenge owing to their rarity, as well as imaging and histologic overlap. Aggressive angiomyxomas (AAM) and cellular angiofibromas are among the more common mesenchymal neoplasms. Angiomyofibroblastoma (AMF), a related but less invasive soft tissue neoplasm that occurs in the same region and patient population, is a differential diagnostic consideration. Additional benign tumors that are discussed include nodular fasciitis, vaginal fibroepithelial polyps, and nonneoplastic cysts.

Aggressive Angiomyxoma

AAM is a benign myxoid neoplasm affecting women in their third to fifth decades of life. It has been reported rarely in men. Patients may present with a mass, but AAMs are often asymptomatic and can become large, sometimes measuring more than 10 cm at presentation. A large intrapelvic component may not appreciated on clinical examination, and these can often be mistaken for a lipoma, perineal hernia, or Bartholin gland cyst. These masses tend to be slow growing. Metastases are rare but have been reported.

The mass arises from the connective tissues of the perineum or lower pelvis, rarely from perineal or pelvic viscera. Grossly, it appears as a rubbery, gelatinous mass. Histologically, the tumor is hypocellullar with stellate and spindle-shaped mesenchymal cells embedded in a loose myxoid stroma.

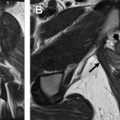

Imaging is important to determine the anatomic extent and relationship to the pelvic floor, perineal tissues, and pelvic viscera to optimize the surgical approach. On MR imaging, the mass is isointense or hypointense to muscle on T1WI. On T2WI, the mass is hyperintense owing to high myxomatous content with a characteristic “swirled” or “whorled” appearance, attributed to stretching of the fibrovascular stroma and disorganized vascular network within the tumor. On postcontrast T1WI, the tumor enhances avidly, sometimes revealing the swirled pattern, demonstrating their hypervascular nature ( Fig. 3 ). In 1 study, AAMs demonstrated high signal intensity on diffusion-weighted imaging with ADC values of more than 2 × 10 −3 mm 2 /s.

Because AAMs tend to grow around and displace pelvic structures without penetration or invasion, patients can have extensive tumor above the pelvic floor with normal sexual, urinary, and anal sphincter function. The tumor does not generally cause rectal, vaginal, urethral, or vascular obstruction.

Surgery with wide local excision is the treatment of choice for AAM. MR imaging is important for surgical planning to determine whether the tumor traverses the pelvic diaphragm, which allows the surgeon to determine if a perineal, abdominal, or combined approach to resection is needed. Complete resection of AAMs is often not possible, hence the term “aggressive,” denoting the high rate of local recurrence after resection (36%–72%). The high local recurrence rate may be owing to diagnostic difficulty before the initial surgery, limiting complete preoperative assessment of tumor extent. Additionally, the intimate relationship of the tumor to pelvic viscera with extension above and below the pelvic diaphragm makes complete resection difficult. Most recurrences are likely owing to inadequate resection and residual tumor. Patients often require multiple resections with wide margins to achieve control or cure. Recurrence may occur, even with negative surgical margins. Long-term follow-up is warranted owing to late recurrence in some cases.

In AAMs that are estrogen and progesterone receptor positive, tamoxifen, raloxifene, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists have been used as neoadjuvant therapy to shrink the tumor and minimize the radicality of surgery and as a treatment for recurrence.

Angiomyofibroblastoma

AMF was characterized as a separate entity from AAM in 1992. It affects the vulvar region of women ages 23 to 71, with a mean age of 42. As with AAM and cellular angiofibroma, AMF often presents as a painless mass. It tends to be well-circumscribed as opposed to the infiltrative nature of AAM. AMFs range in size from 0.5 to 12.0 cm in diameter, with most less than 5 cm. AMFs arise in the superficial soft tissues of the vulva, whereas AAMs often extends into the deep pelvic structures as described, particularly at recurrence.

Histologically, AMF is characterized by alternating hypercellular and hypocellular zones with abundant vessels, predominantly capillaries. AMF is distinguished from AAM by its circumscribed borders, greater cellularity, and more numerous vessels, among other histologic features, which are beyond the scope of this article.

On MR imaging, Mortele and colleagues described AMF to be hypointense and heterogeneous on T1WI with areas of hyperintensity representing interspersed fat contents. On T2WI, the mass may not be well seen owing to hyperintensity of the mass and the surrounding fat, depending on the location. On postcontrast imaging, there is strong, homogenous enhancement owing to hypervascularity. Local surgical excision is often curative and postoperative recurrence is rare, in contrast with AAM.

Cellular Angiofibroma

Cellular angiofibroma, also known as AMF-like tumor, was first characterized as a distinct histologic entity in 1997. It is rare, found in various anatomic sites, such as the perineum, vulva, genital tract, and inguinal regions. Initially thought to only occur in women, it has been described in men in the scrotum and inguinal canal. It occurs in men and women approximately equally. Women are more affected in the fifth decade (ages 39–50), whereas men are mainly affected in the seventh decade. Cellular angiofibromas have a small size (<3 cm) and are usually well-circumscribed, like AMFs. The term cellular angiofibroma was given to highlight the principal histologic components: the cellular spindle cell stromal component and the prominent thick walled blood vessels. There are scarce mature adipocytes.

On MR imaging, it is a circumscribed mass, isointense to muscle on T1WI. On T2WI, it has heterogeneous signal intensity depending on the amount of collagenous stoma, myxoid matrix, spindle cell component, and fat. Often, cellular angiofibroma demonstrates lower signal intensity on T2WI owing to fibrous tissue, fibrosis in the wall, abundant blood vessels, and lack of myxoid tissue. It may have a T2 hypointense rim. On postcontrast T1WI, it is highly vascular and avidly enhancing with solid, homogenous enhancement ( Fig. 4 ).

Treatment consists of simple local excision with clear margins. Most literature cites that these do not recur, although we have seen a case of recurrence in our institution, attributed to malignant degeneration. Thus, close postoperative monitoring and long-term follow-up is recommended; suspected recurrence should be imaged and explored.

AAM, AMF, and cellular angiofibroma are compared in Table 1 .

| Clinical Features | Aggressive Angiomyxoma | Cellular Angiofibroma | Angiomyofibroblastoma |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 3rd to 5th decade (often 35–40) | Women: 5th decade (39–50); men: 7th decade | Young to older women (ages 23–71; mean 42) |

| Sex | F>>M | F = M | F>>M |

| Presentation | Painless mass, effects of pressure on adjacent structures | Painless mass | Painless mass |

| Size of lesion | 3–10 cm (often >5 cm at presentation) | <3 cm | 0.5–12 cm (often <5 cm) |

| Behavior | Infiltrative | Well circumscribed | Well circumscribed |

| MR imaging | |||

| T1W1 | Isointense or hypointense to muscle | Isointense to muscle | Hyperintense (fat) |

| T2Wl | Hyperintense (swirled or whorled pattern) | Heterogenous, often lower T2 signal intensity | Hyperintense (fat) |

| Post contrast | Avidly enhances (may have whorled pattern) | Avidly enhances | Avidly enhances |

| Treatment | Surgical excision; often recurs; metastases have been reported | Surgical excision is often curative; rare recurrence or malignant degeneration | Surgical excision is often curative; rare recurrence |

Nodular Fasciitis

Nodular fasciitis was initially named pseudosarcomatous fibromatosis. This entity has variously been known as pseudosarcomatous fasciitis, infiltrative fasciitis, and proliferative fasciitis, reflecting the limited understanding of this benign, self-limiting condition, despite it being the most common tumor of fibrous tissue. Nodular fasciitis results from a proliferation of fibroblasts, arranged in loose fascicles with a myxoid stroma and multinucleated giant cells. Rapid growth of the lesion, a high mitotic rate and high cellularity can raise concern for a sarcoma both on imaging and pathology.

The condition is typically seen in younger adults; 85% of patients are under 50 years of age. It is rare in the pediatric population, however, accounting for 10% of cases. Clinically, the lesions present as a rapidly growing mass developing over several weeks. These lesions may be tender but tend to be small, less than 5 cm. The lesions may be subcutaneous, within the fascia or intramuscular. Rare cases of intravascular lesions have been described. The most common site of involvement is the upper extremity (46%), but it also commonly involves the head/neck, trunk, and lower extremity. Cases of vulvar involvement have been published. Spontaneous resolution can occur and lesions may respond to intralesional steroid injection. Surgical excision can be performed with a very low rate of recurrence, even with only partial excision.

Lesions may be predominantly fibrous, cellular, or myxoid and, as a result, a variety of MR imaging appearances can be seen. Lesions tend to be isointense to hyperintense to muscle on T1WI and hyperintense to fat on T2WI. There is usually hyperenhancement, although this may be diffuse or peripheral. Pathologically, nodular fasciitis is an unencapsulated but well-demarcated lesion; however, it can be focally infiltrative, manifesting on MR imaging as lesional extension along fascial planes or a “fascial tail” ( Fig. 5 ). In addition, aggressive features such as spread between compartments, bony changes, and intraarticular involvement have been described. Calcification or ossification are rarely seen on radiographs. The “inverted target” sign has been described in nodular fasciitis when there is hyperintense signal centrally on T2WI correlating with an area of relative hypoenhancement after contrast administration. Nodular fasciitis is one of the few benign lesions that can demonstrate central necrosis (along with ancient schwannomas). The appearances are not specific, however, and biopsy is typically necessary to exclude a sarcoma or other aggressive malignancy.

Vaginal Fibroepithelial Polyp

Vaginal fibroepithelial polpys, also known as fibroepithelial stromal polyps or mesodermal stromal polyps, develop in women during their reproductive years, predominantly affecting the vagina, less commonly the vulva, and rarely the cervix. They seem to have a hormonal association, because they are often found in patients who are pregnant at diagnosis, during tamoxifen therapy, or other hormone usage.

Patients most commonly present with a painless mass, although other presentations include skin tags, discharge, and vaginal bleeding. They are usually less than 2 cm in diameter, but can measure up to 12 cm. Lesions may be solitary or less commonly multiple and bilateral. Bilaterality is more frequently encountered in pregnancy.

On gross pathologic examination, fibroepithelial polyps are often pedunculated with polypoid stromal proliferation. Histologically, they are covered with squamous epithelium. The fibrovascular stroma is typically edematous with collagen fibers. Fat may be present and it usually has a vascular component, generally toward the lesion center.

On MR imaging, fibrous tissues presents as stratiform hypointense areas on T2WI. At the center of the attachment site, there may be clustered fatty tissue, which appears as a linear hyperintense area on T1WI. Most of the remainder of the lesion demonstrates increased signal intensity on T2WI owing to edematous stroma with less fibrosis and cellularity. Phase shift T1-weighted gradient echo imaging or equivalent T1WI with fat suppression may demonstrate intralesional fat more clearly. The lesion enhances on postcontrast T1WI ( Fig. 6 ).

Surgical excision is often curative, although local recurrence can occur with incomplete excision. Because they may be hormonally responsive, some recur in pregnancy; others regress during the postpartum period. Metastases have not been reported.

Nonneoplastic Cysts (Bartholin Gland Cyst, Skene Gland Cyst, Clitoral Epidermal Inclusion Cyst)

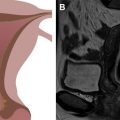

Nonneoplastic cysts affecting the perineum have a similar MR imaging appearance to cysts seen elsewhere in the body ( Fig. 7 ). They are characteristically strongly hyperintense on T2WI, hypointense on T1WI, with no or very thin peripheral enhancement. If there is internal hemorrhage or mucin/protein within the cyst, they may appear hyperintense on T1WI. Any of these can become infected, often causing imaging changes of wall thickening and/or peripheral enhancement.

Cysts can be differentiated based on location ( Fig. 8 ). If a line is drawn from the coccyx to the inferior aspect of the pubic symphysis (pubococcygeal line), Bartholin gland cysts and Skene gland cysts occur below the line. Gartner duct cysts occur above or at the line at the anterolateral aspect of the vagina and are therefore not discussed in this article. Bartholin gland cysts occur at the posterolateral wall of the introitus, whereas Skene gland cysts are anterior to the introitus and more medial, because they are associated with the urethra.

Clitoral epidermal inclusion cysts have a similar MR imaging appearance as Bartholin gland and Skene gland cysts, but are located within the clitoris.

Bartholin gland cysts (see Fig. 7 A–C)

- •

The Bartholin gland is the female homologue of the male Cowper gland.

- •

Bilateral gland ducts open into the posterolateral aspects of the introitus.

- •

Ductal obstruction, which may be owing to a stone or stenosis resulting from prior infection, trauma, or inspissated mucus, leads to secretion retention and cyst formation.

- •

Most common vulvar cysts.

- •

Develop in 2% of women during their lifetime, usually second to third decade of life.

- •

Often asymptomatic, but may present with mild dyspareunia.

- •

1 to 4 cm, but can become larger with repeated sexual stimulation.

- •

Pain may indicate enlargement or infection (most commonly Neisseria gonorrhoeae ).

- •

Symptomatic cysts are treated with marsupialization or surgical excision with or without antibiotics, if infected.

- •

Incision and drainage for abscess with definitive treatment after resolution.

- •

Rarely, squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma can develop in a Bartholin gland duct or cyst, respectively (look for a solid component).

- •

Adenoid cystic carcinoma, more commonly seen in salivary glands, is a rare, slow-growing complication of Bartholin gland cyst with a tendency for local invasion, treated with vulvectomy and bilateral inguinal and femoral node dissection.

- •

Skene gland cysts (see Fig. 7 D–F)

- •

Gland ducts are paired structures lateral to the external urethral meatus.

- •

Open directly into the urethral lumen, anterior to the introitus.

- •

Cysts result from duct obstruction, similar to Bartholin gland cysts.

- •

Differentiate from urethral diverticulum, which tends to be in a midurethral location.

- •

Often asymptomatic.

- •

May cause recurrent urinary tract infection or urethral obstruction.

- •

May require drainage or excision if infected.

- •

Clitoral epidermal inclusion cysts (see Fig. 7 G–I)

Clitoral epidermal inclusion cysts are occasionally spontaneous or can occur after accidental clitoral trauma. However, they are most often seen with prior clitoral surgery and are the most common long-term complication of female genital mutilation, which is more commonly practiced in African countries. According to the World Health Organization, female genital mutilation is defined as all procedures that involve partial or total removal of female external genitalia and/or injury to the female genital organs for nonmedical reasons. Other complications of female genital mutilation include wound infection and labial adhesion.

- •

May be more common than previously thought, possibly underreported in the literature.

- •

Slow growing, intradermal or subcutaneous lesions with a wall composed of true epidermis.

- •

Result from embedding of epidermal keratinized squamous epithelial cells and sebaceous glands into the line of the clitoral circumcision scar; the epidermal cells proliferate within the closed space to form a cyst.

- •

Often contain sebaceous material on gross examination.

- •

Usually asymptomatic, but may be associated with dyspareunia, micturition disturbances, vulvar pain, or vaginal discharge.

- •

May become inflamed or infected, leading to pain or tenderness.

- •

Treatment is surgery with enucleation of the cyst.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree