How to Image Infection ( Box 5-1 )

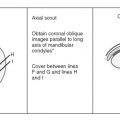

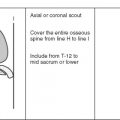

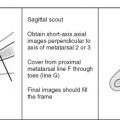

Musculoskeletal infections affect bones, soft tissues, and joints. Infection often is considered a therapeutic emergency, and MRI is used to determine the presence or absence of disease and its extent. The MRI study should be directed to the site of involvement based on clinical grounds or where abnormalities on other imaging studies have been found. The coil used, the patient’s position, the planes of imaging, and the field of view vary for each site.

- •

Coils and patient position: The patient is usually supine in the magnet, unless the region affected involves mainly the posterior soft tissues, such as the buttocks or posterior thoracic cage. Spine phased array coils are used for any portion of the spine; the body coil or, preferably, a large field-of-view phased array coil is used for the thorax, pelvis, and femora; and smaller surface coils are used for the other extremities and joints.

- •

Image orientation: The best imaging planes for the spine are sagittal and axial; for the pelvis, coronal and axial images are preferred; generally, axial and coronal images are used for lesions near the hip, foot, shoulder, and wrist; and lesions near the knee, ankle, and elbow are evaluated best with axial and sagittal images.

- •

Pulse sequences and regions of interest: In the spine, sagittal and stacked axial T1W, fast T2W, and postgadolinium T1W images of the region of interest are obtained. In the pelvis and extremities, our routine protocols include T1, STIR, and postgadolinium T1W images. Section thickness in the spine is 4 mm; in the pelvis, 7 mm; and in the extremities, 4 mm (or larger, depending on the volume to be covered).

- •

Contrast: Intravenous (IV) gadolinium routinely is used for diagnosing musculoskeletal infections. It allows differentiation of an abscess from cellulitis or phlegmon in the soft tissues, or an abscess from bone marrow edema in the marrow space. Gadolinium also increases the conspicuity of sinus tracts and sequestra.

Osteomyelitis

MRI allows for early detection of osteomyelitis, the extent of involvement, and the activity of the disease in cases of chronic osteomyelitis.

DEFINITION OF TERMS ( Box 5-2 )

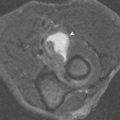

Sequestrum: A fragment of necrotic (dead) bone separated from living bone by surrounding granulation tissue is a sequestrum. This is seen on a radiograph as a dense bone fragment (sequestrum) surrounded by a radiolucency (granulation tissue); on MRIs, the sequestrum is a low signal intensity structure on T1W and STIR sequences, whereas the surrounding granulation tissue is intermediate to low signal intensity on T1W images and high signal intensity with STIR or T2W sequences ( Fig. 5-1 ). With gadolinium, the granulation tissue is enhanced, whereas the sequestrum remains low signal intensity.

Cloaca : Defect in the periosteum created by infection

Involucrum : Thick sleeve of periosteal new bone surrounding dead cortical bone

Sequestrum : Fragment of dead bone surrounded by granulation tissue

Sinus tract : Channel extending from bone to skin surface, lined with granulation tissue

Fistula : Channel between two internal organs

Involucrum: An envelope of thick, wavy periosteal reaction formed around the cortex of an infected tubular bone is known as the involucrum. It commonly is found in bones of infants and children with osteomyelitis. As the infection is controlled, the dead cortical bone is incorporated with the involucrum, forming a thickened cortex (see Fig. 5-1 ). On MRI, the ossified periosteal shell and the dead tubular cortical bone are low signal intensity on all pulse sequences; periosteal reaction and cortical bone are separated by linear intermediate to high signal intensity on T2W or STIR images ( Fig. 5-2 ), until the periosteal reaction and cortical bone are incorporated.

Cloaca: An opening through the periosteum that permits pus from the infected bone to enter the soft tissues is called a cloaca . On MRI, the linear low signal intensity periosteum that is elevated from the cortical bone or the thickened cortex is interrupted by a high signal intensity gap (cloaca) on T2W images (see Fig. 5-1 ). On T2W images, the high signal intensity pus can be seen extending into the soft tissues from the cloaca and may form a sinus tract or abscess.

Sinus Tract/Fistula: A sinus tract is a channel between an infected bone and the skin surface, whereas a fistula is a tract or channel between two internal organs. Sinus tracts and fistulae are lined by vascular granulation tissue, and they function as conduits for pus to flow away from the infected bone. On MRI, a sinus tract or fistula is linear low signal intensity on T1W images, best seen if the subcutaneous fatty tissues are not infiltrated with edema. On T2W images, the channel shows linear high signal intensity as a result of the granulation tissue and pus ( Fig. 5-3 ). The granulation tissue is enhanced after IV injection of gadolinium, and the channel is most conspicuous with a fat-suppressed T1W sequence after contrast enhancement.

Abscess/Phlegmon: A cavity filled with pus that is surrounded by a capsule and lined with granulation tissue is an abscess, whereas a phlegmon is a solid mass of inflammatory tissue. An abscess may be limited to the medullary bone, the cortex, the soft tissues, or more than one of these compartments ( Fig. 5-4 ). On MRI, the abscess and the phlegmon are intermediate to low signal intensity on T1W and high signal intensity on T2W images. After IV injection of gadolinium, the rim of an abscess is enhanced, whereas the center of the mass that contains the pus remains low signal intensity. A phlegmon enhances diffusely.

Penumbra Sign: One imaging finding reported to be helpful in differentiating a subacute or chronic abscess from tumor has been called the penumbra sign . This sign was originally described in cases of subacute osteomyelitis, but it has been found to be useful in identifying soft tissue abscesses as well. It consists of a thin, intermediate signal intensity rim along the periphery of a bone or soft tissue abscess on unenhanced T1W images ( Fig. 5-5 ). Although this appearance is not specific for an abscess, it is highly suggestive, and is thought to be related to a layer of granulation tissue along its wall.

ROUTES OF CONTAMINATION ( Box 5-3 )

Osteomyelitis can develop via three routes:

- 1.

Hematogenous seeding

- 2.

Contiguous spread from an adjacent infection

- 3.

Direct implantation of microorganisms

Hematogenous

- •

Infants (<1 yr)

- •

Metaphysis/epiphysis

- •

- •

Children (1 yr to growth plate closure)

- •

Metaphysis

- •

- •

Adults

- •

Epiphysis

- •

Direct Implantation

- •

Puncture wounds

- •

Human/animal bites

- •

Open fractures

- •

Surgery

Contiguous Spread

- •

Infection starts in soft tissues

↓

- •

Periostitis (periosteal involvement)

↓

- •

Osteitis (cortical involvement)

↓

- •

Osteomyelitis (marrow involvement)

- •

Reverse sequence from hematogenous spread

Hematogenous Seeding

The location of lesions from hematogenous seeding is related to the vascular supply of tissues; in some patients, involvement may be multifocal. In hematogenous osteomyelitis, the contamination begins in the bone marrow and extends secondarily through the cortex and then to the adjacent soft tissues. In the spine, the common initial site of involvement is the subchondral bone of the vertebral body, which is supplied by nutrient arterioles. This process eventually extends to the disk (spondylodiscitis). In children, vascular channels perforate the vertebral end plates, allowing direct access of microorganisms to the intervertebral disk (diskitis) without initial contamination of the vertebral bodies. In tubular bones, the vascular anatomy changes with age and is different for infants, children, and adults. This particular vascular distribution explains the location of lesions for the different age groups.

The infantile pattern (0-1 year) is related to the fetal vascular arrangement that persists up to age 1 year. The metaphyseal and diaphyseal vessels penetrate the growth plate and extend into the epiphysis. In infants, infection affects primarily the epiphysis and the growth plate because of this vascular anatomy. Profuse involucrum formation is characteristic, reflecting the ease with which the periosteum is lifted from the underlying bone in infants and the presence of a rich vascularity. Development of soft tissue abscesses and extension into the joint also are common. Group A streptococcus is the most common organism affecting infants with osteomyelitis.

The childhood pattern is from 1 year of age to closure of the growth plates ( Fig. 5-6 ). The metaphyseal vessels become terminal ramifications of nutrient arteries, with the capillaries forming large sinusoidal lakes in the metaphysis. The slow blood flow in this area contributes to the increased incidence of osteomyelitis that affects the metaphysis in the child. Later, extension into the epiphysis may occur from contiguous spread. Involucrum, sequestrum, and abscess formation are common. Articular extension (septic arthritis) occurs at sites where the growth plate is intra-articular, such as in the hip, elbow, and shoulder. In flat bones, such as the pelvis, childhood osteomyelitis shows a predilection for metaphyseal-equivalent locations adjacent to apophyses (eg, the iliac crests), and for epiphyseal-equivalent locations adjacent to articular cartilage (eg, around the triradiate cartilage) ( Fig. 5-7 ). Staphylococcus aureus (80%) and group A streptococcus are the most frequent organisms that affect children.

The adult pattern of hematogenous seeding of osteomyelitis is seen when growth plate closure has occurred. The diaphyseal and metaphyseal vessels penetrate the fused growth plate, which allows infection to localize in the subchondral bone regions (epiphyses). Septic arthritis may complicate this epiphyseal location. The spine, the pelvis, and the small bones of the hands and feet are the most common sites of infection.

Contiguous Spread

When soft tissues initially are infected, and the noncontained infection extends to adjacent osseous structures, it is considered contamination by contiguous spread ( Fig. 5-8 ). Contamination of bone by contiguous spread most commonly is seen in debilitated patients, in diabetics, and in patients treated with corticosteroids. The soft tissue infection invades bone marrow by progressing in sequence from cellulitis in the soft tissues to periostitis to osteitis to osteomyelitis. Osteitis indicates involvement of cortical bone; extension of the cortical infection into the marrow cavity produces osteomyelitis. The direction of contamination in contiguous spread of infection is the reverse of that which occurs with hematogenous osteomyelitis. With hematogenous osteomyelitis, marrow is affected initially, followed by cortical destruction, then periosteal contamination, and finally soft tissue cellulitis, phlegmon, or abscess.

Direct Implantation

Contamination of tissues by direct implantation of infectious agents is usually the result of puncture wounds, foreign bodies, open fractures, and surgery. Human bites ( S. aureus, Bacillus fusiformis ) and animal bites ( Pasteurella multocida, S. aureus , and Staphylococcus epidermidis ) also are common causes of infection from direct implantation ( Fig. 5-9 ). The infection starts at the site of implantation, which may be in the soft tissues, the periosteum, or the cortical or medullary bone; soft tissue involvement almost always is present ( Fig. 5-10 ).

MRI OF OSTEOMYELITIS ( Box 5-4 )

Osteomyelitis classically is divided into three stages: acute, subacute, and chronic. These stages are based on the patient’s clinical picture, on the duration of the disease, and on imaging findings.

Bone Marrow Inflammation

- •

T1: Low signal intensity

- •

T2: High signal intensity

- •

T1 with contrast: High signal intensity

Intraosseous Abscess

- •

T1: Low signal intensity

- •

T2: High signal intensity

- •

T1 with contrast: High signal intensity only in periphery

Sequestrum

- •

T1: Low signal intensity

- •

T2: Low signal intensity

- •

T1 with contrast: High signal intensity surrounding sequestrum, which remains low signal

Cortical Destruction

- •

T1: Intermediate signal intensity

- •

T2: Intermediate or high signal intensity

- •

T1 with contrast: Intermediate signal intensity

Cloaca

- •

T1: Hard to see

- •

T2: High signal intensity defect in low signal periosteum

- •

T1 with contrast: Not seen

Sinus Tract

- •

T1: Not seen, or linear low signal intensity

- •

T2: High signal intensity

- •

T1 with contrast: High signal intensity in peripheral lining of low signal intensity tract

Acute Osteomyelitis

Acute osteomyelitis of hematogenous origin has normal radiographs in the first week, followed in the next 7 to 14 days by osteoporosis, fine linear periosteal reaction, and eventually permeative or moth-eaten bone destruction. Before radiographic manifestations of infection, MRI shows obliteration of the medullary fat by bone marrow edema, which is high signal intensity on STIR images and low to intermediate signal intensity on T1W images ( Fig. 5-11 ). These MRI features are not specific. MRI is highly sensitive, but not specific for diagnosing infection, with reported specificities for osteomyelitis ranging from 53% to 94%; however, MRI has a negative predictive value for osteomyelitis of close to 100%. As the disease progresses, MRI shows elevation of the periosteum, which is a low signal intensity line on all pulse sequences. The space between the periosteum and cortical bone has intermediate signal intensity on T1W and high signal intensity on STIR images; this usually is accompanied by adjacent soft tissue edema. Cortical destruction is a later finding and is depicted initially by blurring and eventually focal interruption of the cortical line, which is normally completely devoid of signal (low signal intensity) on all pulse sequences.

The infection may transgress the periosteum with formation of a cloaca. This is seen best on STIR images as a high signal intensity defect traversing the black periosteal line ( Fig. 5-12 ). This defect may evolve into an abscess cavity or a sinus tract. An abscess cavity is usually oval in shape, low signal intensity on T1W images, and high signal intensity on T2W images. It may blend in with, and be obscured by, diffuse surrounding edema. The use of gadolinium helps to distinguish an abscess from surrounding edema. The abscess shows high signal intensity enhancement of its capsule, whereas the cavity remains low signal intensity. Cellulitis shows diffuse contrast enhancement.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree