Musculoskeletal Neoplasms

Musculoskeletal neoplasms are treated with surgical excision, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and combination therapeutic approaches. This chapter will focus on orthopaedic approaches to treatment of neoplasms. Emphasis will be placed on the role of imaging in detection and classification and postoperative monitoring.

Preoperative Evaluation

Decisions regarding the approach to musculoskeletal neoplasms may be relatively simple in the case of a localized benign lesion or more complex. The therapeutic decisions may be more complex depending on the histology, location, bone and soft tissue involvement, and patient factors such as age, general health status, activity, and prognosis. Limb-saving procedures, often with extensive reconstruction, are usually considered when the lesion is located in a region that allows complete resection with wide surgical margin. This would require a 6-cm margin for bone and soft tissue sarcomas. Preoperative chemotherapy is often used preoperatively in conjunction with limb-saving procedures.

Limb-saving procedures are usually contraindicated in patients with neurovascular encasement, which would result in functional impairment in the extremity following resection, and in patients with significant pathologic fractures that may result in dissemination of tumor cells. Lower extremity procedures may compromise growth in an immature skeleton. However, new prosthetic designs and other surgical options do not totally exclude limb-saving procedures in children in whom the growth plate may be at risk. Additional considerations for limb-saving procedures include the risk of local recurrence, long-term survival, functional outcome compared to amputation, psychological benefit, and immediate and delayed morbidities of the surgical procedure.

Preoperative assessment includes multiple clinical and imaging factors. Enneking et al. developed a functional system for pre- and postoperative evaluation that scored 7 categories (0 to 5 points) for a total of 35 points. The categories included motion, pain, stability, deformity, strength, functional activity, and emotional acceptance.

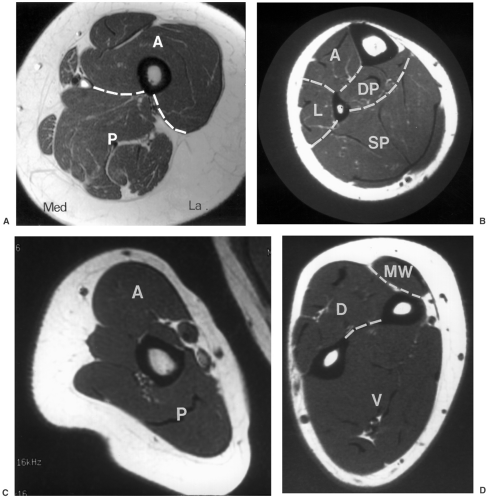

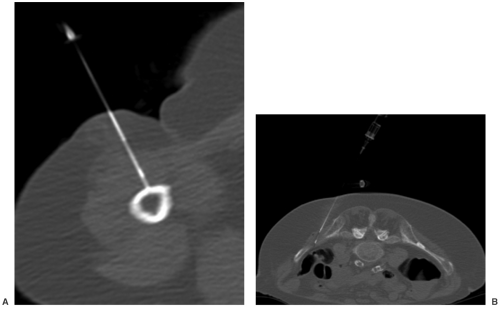

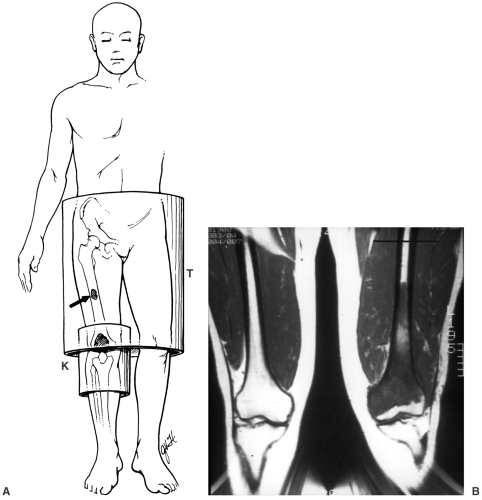

Lesion identification may be accomplished with radiographs or other imaging modalities. Once identified, multiple approaches are used to identify the type of lesion and extent of involvement. This may be initiated with lesion biopsy, followed by additional imaging for staging if the lesion is malignant. Planning the biopsy requires close communication with the orthopaedic surgeon so that the needle path can be resected along with the tumor during the procedure. In addition, knowledge of the anatomic compartments is essential when planning bone or soft tissue biopsies (see Fig. 14-1). Inappropriate needle approaches can unnecessarily contaminate compartments that could interfere with the planned limb-saving procedure. Biopsies are most often performed using computed tomographic (CT) guidance, but ultrasonography or fluoroscopy can also be used to guide needle placement (see Fig. 14-2).

Tumor staging typically involves the lesion (T), grade (G), nodal involvement (N), and metastasis (M). Thorough and accurate staging requires the use of multiple imaging modalities. Multiple staging systems have been used. Enneking et al. proposed a staging system in 1980 that incorporated prognostic factors of local recurrence and metastasis, included surgical implications and provided guidelines for adjuvant therapy. Malignant bone lesions were staged based on grade, inter- and extraosseous extent, and whether there was associated metastasis. This system was later endorsed by the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society (MSTS) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). The MSTS staging system remains the most commonly used system (see Table 14-1).

Using the MSTS system, low-grade bone lesions are considered stage I and high-grade lesions stage II. Metastases

are considered stage III regardless of the histology. The stages are subdivided based on local extent. Lesions confined to bone are substage A (intracompartmental). Lesions that extend through the cortex into the soft tissues are substage B (extracompartmental).

are considered stage III regardless of the histology. The stages are subdivided based on local extent. Lesions confined to bone are substage A (intracompartmental). Lesions that extend through the cortex into the soft tissues are substage B (extracompartmental).

Table 14-1 STAGING OF MALIGNANT MUSCULOSKELETAL NEOPLASMS | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Imaging of primary skeletal or soft tissue lesions and potential metastasis requires multiple modalities to optimize staging. Over the years accuracy has greatly improved with the additions of CT, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomographic (PET) imaging. To assist the clinician, the radiologist must identify all of the following features so that they can be correlated with the staging system:

Imaging features for tumor staging

Tumor location and size (greatest diameter)

Intra- or extracompartmental

Soft tissue involvement

Joint involvement

Neurovascular displacement or encasement

Skip lesions

Local and distant metastasis

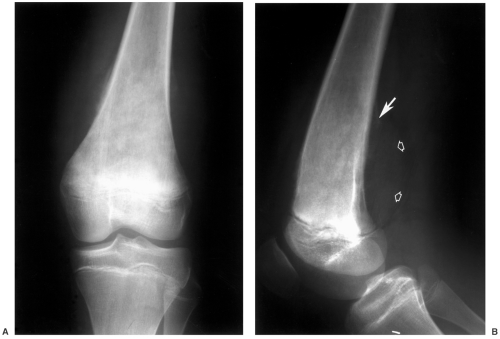

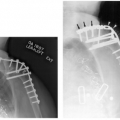

Primary Skeletal Lesions

Radiographs or computed radiographic (CR) images are still useful for detection of benign and malignant skeletal lesions. Radiographic features are extremely useful for characterizing the aggressiveness of the lesion (see Fig. 14-3). In addition, CT is useful in patients with subtle lesions, soft tissue calcification, tumor matrix, and thin cortex (see Fig. 14-4). MRI with contrast is most useful for evaluation of local bone, soft tissue compartment, and neurovascular involvement. The bone and soft tissue anatomy for at least 6 cm about the lesion should be

evaluated to assess the ability to perform and extent of resection for limb-saving procedures.

evaluated to assess the ability to perform and extent of resection for limb-saving procedures.

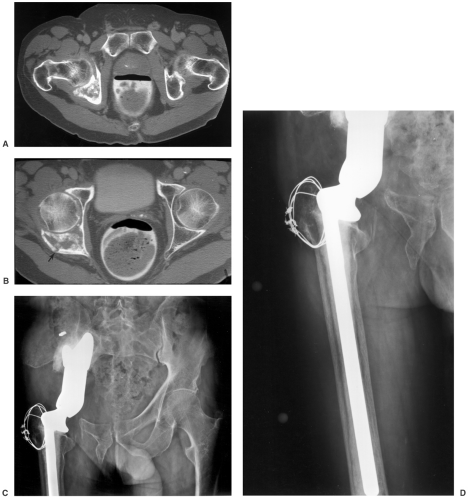

For skeletal lesions, the entire structure (i.e., entire femur and proximal and distal articulations) should be included on the image for operative planning and to exclude skip lesions (see Fig. 14-5). Images should be obtained in at least two planes using T1- and T2-weighted sequences. Additional imaging with short T1 inversion recovery (STIR) may be indicated in some cases. Post–contrast-enhanced (gadolinium) images are routinely obtained unless there is a history of allergy or renal compromise. The same approach should be used postoperatively to establish a baseline for patient follow-up (see Fig. 14-6).

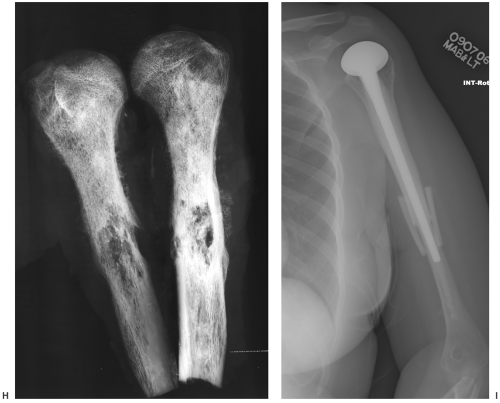

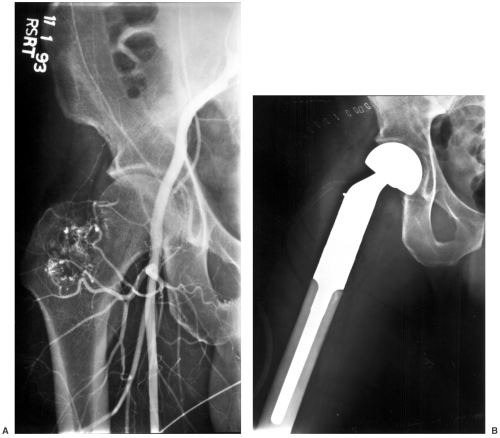

Angiography may be necessary in some cases to define neovascularity and vascular displacement or encasement (see Fig. 14-7). Angiography can also be used preoperatively to deliver chemotherapy and embolize tumor vessels.

Soft Tissue Neoplasms

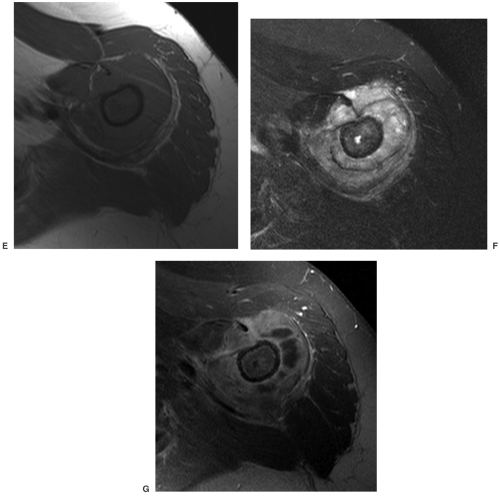

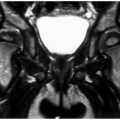

Radiographs demonstrate bone changes and soft tissue calcification. Fatty lesions may also be evident on radiographs. MRI is the technique of choice for detection and local staging of soft tissue lesions. Certain benign lesions such as lipomas, myxomas, hemangiomas, and cysts have characteristic appearances, which may obviate the need for biopsy or surgical intervention (see Fig. 14-8). Malignant or indeterminate lesions are evaluated using T1- and T2-weighted conventional or fast spin-echo sequences with or without fat suppression. Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted images are also obtained. Two image planes are necessary to fully evaluate the extent, compartment, and neurovascular involvement (see Fig. 14-9). Dynamic gadolinium techniques may be of value for differentiating benign from malignant lesions. Angiography is not often performed, but can be used for indications noted earlier.

Metastasis

Radionuclide bone scans with technetium Tc 99m methylene-diphosphonate (MDP) have long been the standard for detection of skeletal metastasis. With a few exceptions (myeloma, aggressive lytic lesions) this technique is still useful (see Fig. 14-10). MRI can be used for axial skeleton screening with axial and sagittal spine images and coronal images of the pelvis and hips using T1-weighted and/or STIR images. PET,

especially PET/CT, plays an important role in tumor staging (see Fig. 14-11).

especially PET/CT, plays an important role in tumor staging (see Fig. 14-11).

Suggested Reading

Bancroft LW, Peterson JJ, Kransdorf MJ, et al. Compartmental anatomy relevant to biopsy planning. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2007;11:16–27.

Enneking WF. Staging of musculoskeletal neoplasms. Skeletal Radiol. 1985;13:183–194.

Heck RK, Peabody TD, Simon MA. Staging of primary malignancies of bone. Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:366–375.

Liu PT, Valadez SD, Chiver FS, et al. Anatomically based guidelines for core needle biopsy of bone tumors: Implications for limb-sparing surgery. Radiographics 2007;27:189–206.

Peabody TD, Gibbs CP, Simon MA. Evaluation and staging of musculoskeletal neoplasms. J Bone Joint Surg. 1998;80A:1204–1218.

Stacy GS, Mahal RS, Peabody TD. Staging of bone tumors: A review with illustrative examples. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:967–976.

Tateishi U, Yamaguchi U, Seki K, et al. Bone and soft-tissue sarcoma: Preoperative staging with Fluorine 18 Fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT and conventional imaging. Radiology 2007;245:839–855.

Treatment Options

Limb-saving procedures for bone lesions are indicated in the following circumstances:

Tumor in the axial skeleton or extremity

Margins amenable to surgical resection

Only moderate soft tissue extension

Neurovascular structures intact

Metastasis absent or can be resected

Patient in good general health

Fig. 14-7 A: Preoperative angiogram demonstrating neovascularity in a malignant tumor in the proximal femur. B: The proximal femur was resected and a custom bipolar prosthesis was inserted. |

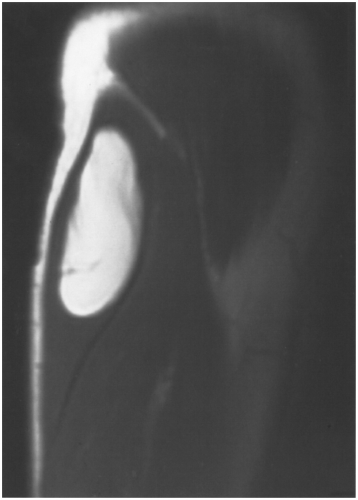

Fig. 14-8 Benign lipoma. Coronal T1-weighted magnetic resonance (MR) image of the proximal arm demonstrating the characteristic appearance of a benign lipoma with a few well-defined fibrous septae. |

Contraindications include the following:

Neurovascular encasement

Surgery would lead to functional impairment

Significant pathologic fracture with tumor cell dissemination

Poorly placed biopsy incisions (relative contraindication)

Treatment options vary with the site, tumor histology, extent of the lesion, and patient comorbidities. In some cases, implants used for fracture treatment or conventional arthroplasty can be used (Fig. 14-10). This section will focus on techniques used for limb-saving procedures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree