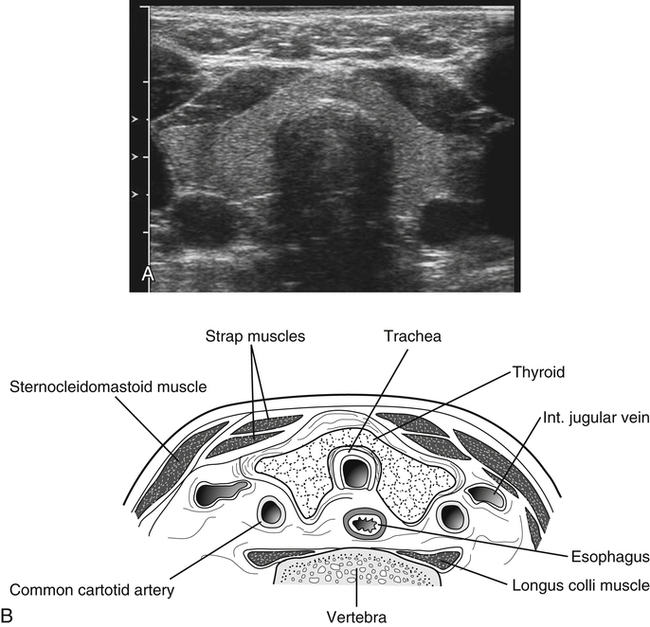

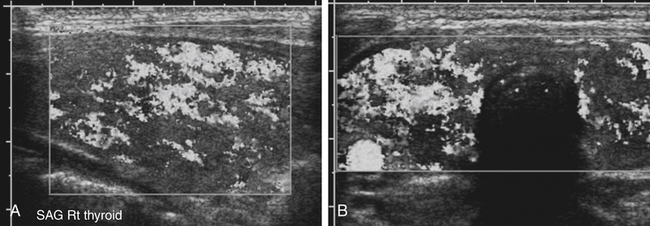

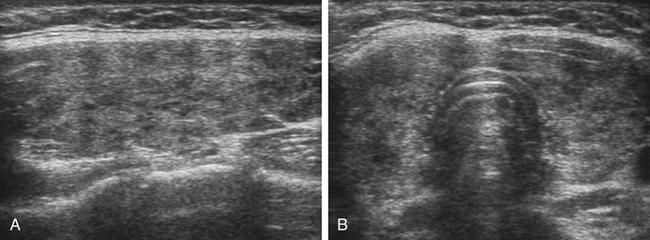

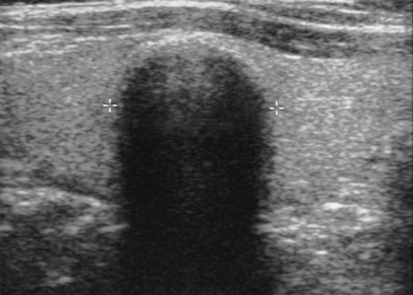

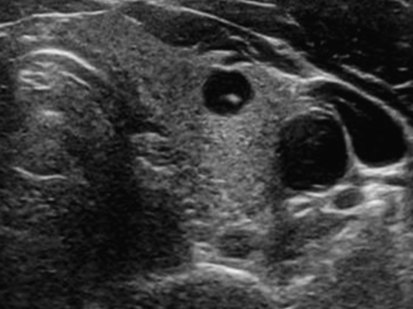

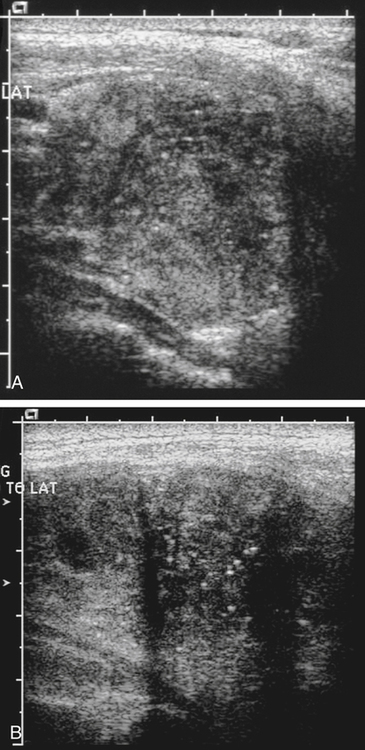

• Name the most common neck masses encountered on sonographic examinations. • List risk factors associated with the development of neck masses. • Describe the sonographic appearances of the most commonly seen neck masses. • Identify sonographic features that suggest a thyroid nodule is benign or malignant. • List the risk factors, laboratory values, and sonographic features of parathyroid adenoma. • Describe less common cystic neck pathologies that can be diagnosed with sonography. The thyroid gland is part of the endocrine system, which helps the body to maintain a normal metabolism. The thyroid consists of paired right and left lobes in the lower anterior neck. The lobes are joined at the midline by a thin bridge of thyroid tissue called the isthmus, which is draped over the anterior aspect of the trachea at the junction of the middle and lower thirds of the gland (Fig. 29-1). A midline pyramidal lobe that arises from the isthmus and tapers superiorly, anterior to the thyroid cartilage, is seen in some patients. Anterior to the thyroid surface are the strap muscles of the neck, the sternohyoid and sternothyroid. The large sternocleidomastoid muscles are located anterolaterally. The carotid sheath, which contains the common carotid artery and the jugular vein, is located laterally. The wedge-shaped longus colli muscles are located posteriorly. In the midline, the shadowing air-filled trachea generally hides the esophagus, but the esophagus may be seen protruding slightly laterally and can be confused with a parathyroid adenoma with imaging in the transverse plane only. Graves’ disease is an autoimmune disorder characterized by thyrotoxicosis and is the most frequent cause of hyperthyroidism. Graves’ disease usually produces a diffusely hypoechoic thyroid texture, with accompanying contour lobulation but without palpable nodules. A characteristic increase in color flow Doppler in the thyroid is present on examination, both in systole and in diastole, leading to the term “thyroid inferno,” coined by Ralls et al.1 (Fig. 29-2; see Color Plate 48). Hashimoto’s disease is the most common form of thyroiditis. The typical clinical presentation is a painless, diffusely enlarged gland in a young or middle-aged woman. The sonographic appearance of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is well recognized. The gland is often diffusely enlarged, and the parenchyma is coarsened, hypoechoic, and often hypervascular. Also seen are multiple ill-defined hypoechoic areas separated by thickened fibrous strands (Fig. 29-3). A micronodular pattern on sonography is highly diagnostic of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Color Doppler imaging usually demonstrates increased vascularity. In the final stages of the disease, a fibrotic gland may be seen that is small, ill-defined, and heterogeneous. Because of the increased risk for malignant disease associated with Hashimoto’s disease, follow-up examinations are recommended. Discrete thyroid nodules with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis are less common. However, discrete nodules may also occur within diffusely altered parenchyma or within sonographically normal parenchyma.2 The sonographic features and vascularity of nodular Hashimoto’s thyroiditis are variable and overlap with the findings typically associated with other benign nodules as well as malignant nodules. A “typical” sonographic appearance for nodular Hashimoto’s thyroiditis has not been reported.2 Thyroid nodules are very common. In the United States, 4% to 8% of adults are estimated to have thyroid nodules, which can be detected with palpation. Of thyroid nodules, 10% to 41% are visible with ultrasound, and 50% are discovered at autopsy.3 The prevalence of thyroid cancer increases with age. The likelihood that a nodule is malignant is affected by several risk factors. Thyroid cancer is more common in patients younger than 20 years or older than 60 years.4 History of neck radiation or a family history of thyroid cancer also increases the risk that a thyroid nodule is malignant. However, thyroid cancer is rare. Most nodules that the sonographer encounters are benign and not clinically significant. In a patient who is referred or has a palpable thyroid nodule, the challenge is to distinguish significant malignant nodules from the many benign ones and to identify patients for whom FNA or surgery is indicated.3 Benign nodules either are hyperplastic (involution of underlying thyroid tissue) or are adenomas, also called follicular adenomas. Adenomas are true thyroid nodules but are less common than hyperplastic nodules, and follicular adenomas are much more common than follicular carcinomas. In contrast to carcinomas, adenomas have no vascular or capsular invasion but otherwise have similar cytologic features. However, in most clinical cases of suspected follicular neoplasm encountered in day-to-day practice, the sonographic features cannot confidently, prospectively distinguish follicular carcinoma from follicular adenoma.5 Sonographically, palpable thyroid nodules can be seen with a high degree of accuracy. However, the differentiation of benign from malignant nodules on the basis of sonographic appearance is challenging. Features that suggest a benign nodule include nodules that are mostly cystic. These cystic nodules almost always contain debris (Fig. 29-4). A nodule with multiple microcystic spaces separated by thin septa or intervening isoechoic parenchyma (a “spongiform” appearance) is also predictive of benignity.6 Less common types of benign nodules are nodules that are hyperechoic relative to the adjacent thyroid parenchyma and nodules that have peripheral eggshell-type calcification (Fig. 29-5). The sonographic features predictive of malignant nodules have been well reported and include the presence of microcalcifications, hypoechogenicity, irregular (spiculated) margins, the absence of a halo, a predominantly solid composition, a shape taller than wide, and intranodular vascularity. The diagnostic accuracy of the sonographic criteria for malignancy depends on tumor size. Specifically, a lower frequency of microcalcifications in microcarcinomas suggests that microcalcification is not a major predictor of malignancy in nodules 1 cm or smaller.7 Most thyroid cancers appear solid and hypoechoic. The significance of peripheral, eggshell or rim calcification for differentiating a benign from a malignant thyroid nodule is debated. Studies have shown that a hypoechoic halo and disruption of peripheral, eggshell calcification are findings that suggest malignancy.6 A wide, irregular halo surrounding the nodule and fine punctate internal calcifications known as psammoma bodies are features commonly seen with papillary thyroid cancer (Fig. 29-6). Hypervascularity in the central portion of the nodule has not proven to be useful to predict malignancy with a high degree of confidence.3 Most follicular tumors are solid and have homogeneous echogenicity. They can be hyperechoic, isoechoic, hypoechoic, or mixed with well-defined areas of different echogenicity within the tumor. Focal cystic components may be present. They usually have a “spoke-and-wheel”–like vascularity with marked circulation in the peripheral halo with vessels converging toward the tumor center.8 The sonographic features of follicular adenoma and follicular carcinoma are very similar making a sonographic distinction challenging, but larger lesion size, lack of a sonographic halo, hypoechoic appearance, and absence of cystic change favor a diagnosis of follicular carcinoma.5 Other types of cancers include anaplastic and medullary cancers. Sonographic findings of these other malignancies are different from the findings of a typical papillary carcinoma (see Table 29-1).6 TABLE 29-1 Pathology of Thyroid, Parathyroid, and Neck ∗Features of follicular adenoma and carcinoma are very similar (adenoma is more common); extensive cytologic and histologic sampling may be necessary for diagnosis, but larger lesion size, lack of a sonographic halo, hypoechoic appearance, and absence of cystic change favor a diagnosis of follicular carcinoma.5

Neck Mass

Thyroid Gland

Normal Sonographic Anatomy

Diffuse Disease

Thyroid Mass

Benign Nodules

Sonographic Findings

Malignant Nodules

Sonographic Findings

Pathology

Symptoms

Sonographic Findings

Adenoma

Usually asymptomatic; possibly palpable

Well-marginated, mostly cystic with internal debris

Adenopathy (cervical)

Variable depending on cause; possibly palpable

Loss of normal flattened, elongated oval lymph node shape with increase in anteroposterior dimension; loss of fatty hilum

Anaplastic thyroid cancer

Painful rapid enlargement of nodule; may mimic thyroiditis

Inhomogeneous hypoechoic invasive solid mass

Branchial cleft cyst

Painless mass on lateral neck; if infected, may be tender and painful

Noninfected—thin uniform wall surrounding homogeneous mass; usually fluid-filled; infected—low-level echoes, layering effect, or complex appearance

Thyroglossal duct cyst

Usually asymptomatic; may cause pain if infected

Well-defined, thin-walled, anechoic mass with through enhancement; mass with mixed echogenicity suggests infection of the cyst; midline or just off midline in position; can be found at any level from the base of the tongue to the isthmus of the thyroid gland

Cystic hygroma

Painless, soft, semifirm mass in posterior neck

Usually multiloculated homogeneous cystic masses

Follicular tumors

Usually asymptomatic; possibly palpable

May be hyperechoic, isoechoic, hypoechoic, or mixed with well-defined areas of different echogenicity within; focal cystic components may be present; usually have a “spoke-and-wheel”–like vascularity with marked circulation in peripheral halo∗

Goiter

Enlargement of thyroid

Nonspecific

Graves’ disease

Symptoms associated with hyperthyroidism

Diffuse hypoechoic thyroid texture; hypervascular

Hashimoto’s disease (chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis)

Painless, diffusely enlarging gland

Ill-defined hypoechoic areas separated by thickened fibrous strands; coarse but overall homogeneous thyroid echotexture; frequently hypervascular

Parathyroid adenoma/parathyroid hyperplasia

Increased levels of serum calcium and parathyroid hormone; hypophosphatasia; increased renal excretion of calcium; nephrocalcinosis and renal stones

Single or multiple oval homogeneous low-echogenicity solid masses; if minimally enlarged, may not be detected with sonography

Medullary thyroid cancer

Possible palpable nodule; increased calcitonin level

Discrete tumor in one lobe or numerous nodules involving both lobes; possible focal hemorrhage, necrosis, coarse calcification, and reactive fibrosis in tumor

Papillary thyroid cancer

Possible palpable mass

Variable, but almost always mass of low echogenicity; wide, irregular halo surrounding nodule often multicentric; internal microcalcifications (psammoma bodies) are a common and specific finding

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Neck Mass