Epithelial tumors

Benign

Malignant

Urothelial papilloma and inverted papilloma

Urothelial carcinoma (transitional cell carcinoma)

Squamous papilloma

Squamous cell carcinoma

Villous adenoma

Adenocarcinoma

Nonepithelial tumors

Benign stromal tumors

Malignant stromal tumors (sarcomas)

Fibroepithelial polyps

Leiomyosarcoma

Leiomyoma

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Neurofibroma

Osteosarcoma

Hemangioma

Fibrosarcoma

Periureteric lipoma

Angiosarcoma

Malignant schwannoma

Ewing sarcoma

Miscellaneous, others

Metastases

Lymphoma

Neuroendocrine tumors

Imaging Findings and Pathological Features

Epithelial Tumors

Benign epithelial tumors are urothelial papilloma and inverted papilloma, which are extraordinarily rare and detected incidentally. Malignant epithelial tumors account more than 90 % of all renal pelvis and ureteral tumors. Approximately 90 % of malignant tumors are urothelial carcinomas (transitional cell carcinomas), followed by squamous cell carcinoma (10 %) and adenocarcinoma (less than 1 %).

Benign Epithelial Tumors

Urothelial Papilloma

General Information

Benign exophytic papillary urothelial tumor

Tends to occur in younger patients

Usually presents with gross hematuria

Imaging

Intravenous Pyelography

Radiolucent filling defect in continuity with the wall of the collecting system

Ultrasonography

Echogenic focus within the ureter and renal pelvis associated with the moderate to severe hydronephrosis

Computed Tomography

A ureteral or renal pelvis mass with attenuation in the soft-tissue range of 30–40 Hounsfield units

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance urography demonstrates the localization and extent of tumor by showing hypointense filling defect in renal pelvis and ureter on heavily T2-weighted images.

Pathology

Urothelial papilloma in these sites is rare. It is a mucosal lesion composed of a delicate papillary frond lined by typical urothelium of normal thickness. It is morphologically similar to its counterpart in the urinary bladder.

Differential Diagnosis

Papillary neoplasm of low malignant potential is a papillary urothelial neoplasm. Mean age of this disease is 64.6 years.

Transitional cell carcinoma, blood clots, and fungus balls.

Pearls and Pitfalls

Urothelial papilloma tends to occur in younger patients.

MR urography may show benign characteristics of this tumor by demonstrating the absence of periureteral or perirenal invasion.

Inverted Papilloma

General Information

It is generally considered a benign histologic lesion; however, it may harbor malignant change.

Median age is 55.

Frequently presents with hematuria.

Imaging

Intravenous Pyelography

Solitary solid, sessile or pedunculated, polypoid lesion

Ultrasonography

Echogenic mass within the ureteral lumen resulting in partial or complete urinary tract obstruction

Computed Tomography

Hypodense mass seen as filling defect in ureteral lumen. Delayed phase images at CT urography may clearly demonstrate.

Pathology

Inverted papilloma is more common in the ureter than the renal pelvis. It is also more common in older males.

Inverted papilloma consists of typical urothelium that forms trabeculae which undermine the overlying mucosa. It is morphologically similar to its counterpart in the bladder.

Differential Diagnosis

Benign and malignant neoplasms of ureter, radiolucent stones, and blood clot

Pearls and Pitfalls

Inverted papillomas of the renal pelvis and ureter may be associated with urothelial neoplasms elsewhere in the urothelial tract.

Urothelial carcinomas may coexist with or arise within inverted papillomas.

Inverted papillomas may recur.

Malignant Epithelial Tumors

Urothelial Carcinoma (Transitional Cell Carcinoma)

The most common epithelial tumor of renal pelvis and ureter. Epidemiology of urothelial carcinoma differs among geographical areas; the highest incidence is in Australia, North America, and Europe, whereas the lowest rates are in South and Central America and in Africa.

Associated etiological risk factors include smoking, long-term analgesic use (particularly phenacetin), and occupational exposure of certain chemicals (such as aniline, benzidine, aromatic amines, coal, tar, thorium). Balkan nephropathy, horseshoe kidney, and stones with chronic inflammation are known to have relation with the development of urothelial carcinoma in the pelvicaliceal system. Incidence of transitional cell tumor in patients with Lynch syndrome II is 6 %.

Pelvicaliceal epithelial carcinomas are two to four times more common than ureter tumors. As seen in bladder tumors, synchronous and metachronous urothelial tumor developments at other sites are quite frequent.

In 80 % of patients with upper urinary system urothelial tumors, a previous history of bladder carcinoma is present, and about 50 % of patients with primary diagnosis of upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma develop bladder carcinoma in their rest of life.

The tumors may be bilateral in 1–2 % of cases with pelvicaliceal urothelial carcinomas.

Synchronous tumors in ureter are more frequent with a rate of 2–9 %.

Imaging

Plain Film Radiography

Conventional x-rays have limited role in diagnosis. Calcification may be present in 2–7 % of cases, however, may mimic calculi and has no diagnostic value.

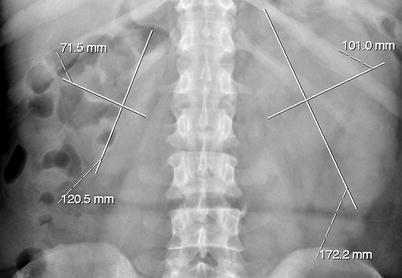

An enlarged kidney may be detected due to hydronephrosis or due to the tumor itself in the very advanced stage (Fig. 8.1).

Fig. 8.1

Plain film radiography demonstrates nonspecific enlargement of the left kidney in a patient with urothelial carcinoma

Intravenous Pyelography

Pelvicaliceal tumors have typical intravenous pyelogram findings which include the following:

Filling defects – Smooth, irregular or stippled, single or multiple filling defects of the pelvicaliceal system (Figs. 8.2 and 8.3).

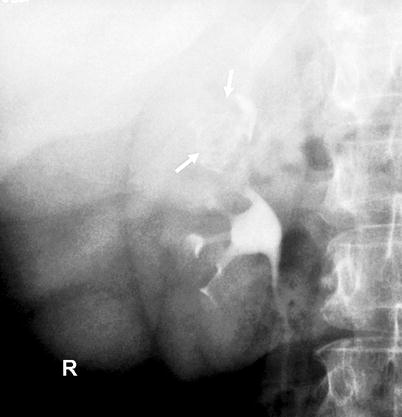

Fig. 8.2

Polypoid tumor of the left renal pelvis seen as a smooth filling defect (arrows) on excretory phase of intravenous pyelography

Fig. 8.3

Tumor at the right renal pelvis seen as a filling defect. The spaces between the papillary projections of the tumor are filled with contrast materials (arrows) resulting in “stippled appearance”

Stipple sign – Occurrence of stipple contrast accumulation within the tumor.

Oncocalyx – Tumor-filled, distended calices (Figs. 8.4 and 8.6).

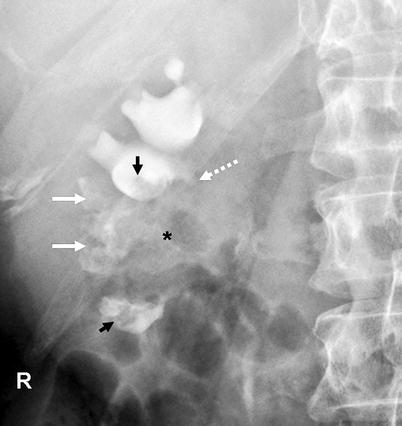

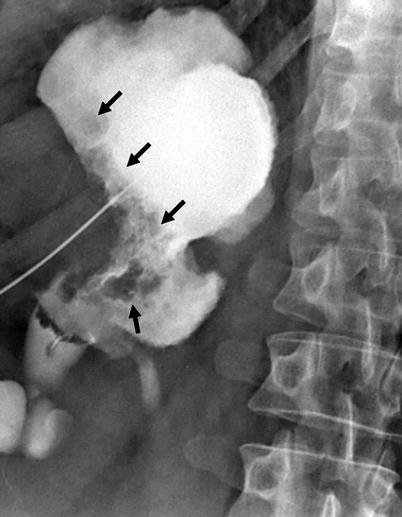

Fig. 8.4

Renal pelvis tumor (*) extending to the mid- and lower-pole calices. Tumoral extension to the calices resulted in “oncocalices” in some calices (white arrows) and appeared as multiple irregular filling defects in some others (black arrows). Infundibular stenosis of the upper-pole major calyx is denoted by dotted arrow

Fig. 8.5

Renal pelvis tumor with loss of opacification of mid- and lower-pole calices (white arrows). Caliceal dilatation of the upper pole is also seen (black arrows). The lower-pole calices involve multiple calculi (*)

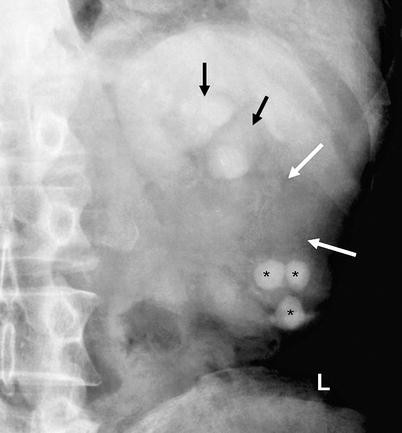

Fig. 8.6

Tumor-filled, distended calyx of the upper pole (“oncocalyx”) (arrows)

Phantom calyx – Unopacified calyx secondary to obstruction of infundibulum. Causes of a phantom calyx include tuberculosis, tumor, calculus, ischemia, trauma, and congenital anomaly.

Ureteral tumors are observed as ureteral filling defect with variable proximal ureteral dilatation. Complete or long-standing obstruction may cause the loss of function of kidney on the affected side; nonfunctioning kidney may be the only finding.

Antegrade and Retrograde Pyelography

Pelvicaliceal tumors in retrograde pyelography have similar findings with intravenous pyelography, though better depiction may be achieved.

Tumors are seen as smooth or irregular intraluminal filling defects, mucosal nodularity, or papillary projections in the involved calices.

Dilatation of involved calices, tumor-filled, distended calices (oncocalices), and nonopacification of calices (caliceal amputation) may be seen (Fig. 8.7).

Fig. 8.7

Antegrade pyelography showing dilatation of renal pelvis and all calices. Irregular filling defects due to tumor are seen (arrows)

In ureteral transitional cell tumors, the transition between the normal mucosa and tumor may show an angulation known as the “shoulder sign” (Fig. 8.8).

Fig. 8.8

Tumor at proximal ureter (black arrows) appears as a concentric filling defect. “Shoulder sign” (white arrow) is diagnostic when detected, which occurs due to acute angulation at the transition zone of tumor and normal wall

Concentric tumors cause the appearance of an “apple core” with mucosal irregularity (Fig. 8.9).

Fig. 8.9

Tumor at distal ureter (arrow) in an appearance of an “apple core” with luminal narrowing and mucosal irregularity

Polypoid filling defect, which may be smooth or irregular (Fig. 8.10).

Fig. 8.10

Antegrade pyelography image of a ureteral tumor seen as a smooth filling defect (arrow)

“Goblet sign” refers to the localized ureteric dilatation around and distal to the filling defect that occurs due to a slowly growing tumor obstructing the ureteric lumen which does not allow the opacification of proximal ureter.

Catheter of the retrograde pyelography coils below the mass (“catheter coiling sign” or “Bergman sign”).

Ultrasonography

Focal or generalized dilatation of the collecting system and concurrent loss of renal parenchyma at the areas of dilatation, depending on the duration and severity of the obstruction.

A soft-tissue mass that is hyperechoic relative to renal parenchyma is observed. Echogenicity may become heterogeneous in high-grade tumors or in tumors that gained large dimensions at the time detection.

Infiltration of renal sinus and parenchyma and perirenal tissues may be present at the time of diagnosis.

Doppler ultrasound imaging may depict the tumor vascularity and can be used for investigation of renal vein patency.

Ureteral tumors appear as intraluminal eccentric or concentric soft-tissue masses with proximal distention of the ureter and pelvicaliceal system (Fig. 8.11).

Fig. 8.11

Longitudinal sonogram of left ureter demonstrating a soft-tissue mass (arrows). (a) The tumor is originating from the posterior wall causing proximal ureteral dilatation. (b) The vascularity of tumor is seen on color flow Doppler image

Computed Tomography

On precontrast images, the tumors are usually hyperdense compared to urine and renal parenchyma (Fig. 8.12).

Fig. 8.12

(a) Precontrast CT image demonstrating the renal pelvis tumor (arrows) in higher attenuation than urine and in similar density with the renal parenchyma. (b) Postcontrast cortical-phase CT image demonstrating the enhancing renal pelvis tumor (arrows). The enhancement is less than the renal cortex

On postcontrast arterial-phase images, tumor enhances moderately and less than the renal parenchyma (Figs. 8.13 and 8.14). At the parenchymal areas corresponding to tumor-involved calices, cortical nephrogram is delayed, which is a helpful sign in diagnosis (Fig. 8.13).