Cross-sectional imaging modalities including ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonancy imaging (MRI) provide good anatomic detail of the abdominal wall and allow evaluation of pathologic processes in this area. Ultrasonography is frequently used as the first imaging modality to explore a palpable abdominal mass.

Non-neoplastic Conditions

Abdominal Wall InflamMation, Infection, and Fluid Collection

Etiology

Inflammatory processes involving the abdominal wall include diffuse edema ( Figure 83-1 ), infections such as cellulitis or abscess, and sterile collections (seroma or liquefying hematoma) ( Figure 83-2 ).

Fluid collections of the abdominal wall commonly result from trauma, postsurgical wound complication, or extension from an intra-abdominal source ( Figures 83-3 and 83-4 ).

Abdominal wall infections also can manifest as necrotizing fasciitis. This condition is considered a true surgical emergency.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Spontaneous infection of the abdominal wall is infrequent in the general population. It is more commonly seen in patients with diabetes mellitus, immunosuppressant therapy, sepsis, surgery, trauma, atherosclerosis, alcoholism, obesity, and malnutrition.

Clinical Presentation

Clinical recognition of fluid collections or inflammatory processes can be difficult, and patients may present with fever, pain, and skin changes.

Pathology

Pathologic and laboratory findings vary according to the specific type of infection.

Imaging

Infectious involvement of the abdominal wall may manifest as cellulitis with poorly defined inflammatory changes in the subcutaneous fat tissue or as a well-defined collection (abscess). CT and MRI provide key information regarding the nature and extent of the infection.

Radiography.

Conventional radiographs have no role in assessing infection and collections of the abdominal wall.

Computed Tomography.

On CT, abscesses appear as low-attenuation fluid collections, often with enhancing margins and gas or gas/fluid levels. Diffuse inflammatory stranding of adjacent structures also is seen. Necrotizing fasciitis can be seen as soft tissue gas dissecting fascial planes in a characteristic appearance. CT plays an important role in guiding percutaneous aspiration or drainage procedures.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

Abscesses are often heterogeneous but generally appear hypointense on T1-weighted sequences and hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences with peripheral enhancement and inflammatory changes in the adjacent tissues.

Ultrasonography.

Fluid collections complicated by infection or hemorrhage have a complex appearance on ultrasound with echoes and internal septa.

Imaging Algorithm.

Ultrasonography is the mainstay for diagnosis of abdominal wall abscesses; however, in obese or postoperative patients, in whom ultrasound evaluation is limited, multidetector CT (MDCT) or MRI should be considered ( Table 83-1 ).

- •

Cellulitis appears as diffuse inflammatory changes involving the skin and subcutaneous tissue.

- •

Abscesses appear as fluid collections, with enhancing margins and surrounding inflammatory changes.

| Modality | Accuracy | Limitations | Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radiography | Limited availability of source literature for comparing accuracy of different imaging modalities for detecting non-neoplastic pathology of the abdominal wall | Not useful | |

| CT | Ionizing radiation | ||

| MRI | Expensive and not widely available Limited spatial resolution Limited on postoperative patients Patient-limiting factors (e.g., claustrophobia, pacemaker) | ||

| Ultrasonography | Obesity, significant scarring, patients with acute abdominal pain Operator dependent Requires high-frequency transducer | If near field is overlooked, abdominal wall pathologic process may be missed. |

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of abdominal wall collections includes uninfected seroma, hematomas, and abscess. Image-guided aspiration with bacteriologic analysis may be needed to differentiate between these entities.

Treatment

Therapy includes antimicrobial therapy and percutaneous drainage. Surgical management is usually required in severe conditions or in cases of necrotizing fasciitis.

Traumatic Abnormalities, Including Abdominal Wall Hematoma

Etiology

Traumatic injuries include laceration, contusion, hematoma, and muscle tear. Abdominal wall hematomas may be associated with trauma, anticoagulation therapy, and blood dyscrasias. Abdominal wall hematomas commonly involve the anterior or anterolateral muscle groups.

Groin, or retroperitoneal hematoma may occur as a complication of arterial or venous catheterization.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Trauma may result in abdominal wall abnormalities that can be detected on imaging studies, including abdominal wall laceration ( Figure 83-5 ), hematoma, contusion, and muscular tear ( Figure 83-6 ).

Clinical Presentation

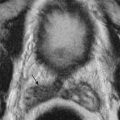

Above the arcuate line, wall hematomas are confined within the rectus sheath, they are oval ( Figure 83-7 ), and they manifest with pain and tenderness. Below the arcuate line and because of the absence of the posterior rectus sheath, the hematoma is unconfined; it can leak and dissect posteriorly into the extraperitoneal spaces, across the midline in the prevesical space (Retzius’s space), or laterally into the flank, predisposing to hypovolemic shock secondary to uncontained blood loss ( Figure 83-8 ).

Pathology

Trauma may affect skin, subcutaneous tissues, and muscles of the abdominal wall.

Imaging

Computed Tomography.

On CT, acute hematoma is hyperdense relative to muscle because of clot formation. Attenuation values decrease with time as breakdown of blood products occurs. Chronic hematoma may be isodense or hypodense relative to surrounding muscle.

A classification method for rectus sheath hematoma has been described on the basis of CT findings, as follows :

- •

Type 1: The hematoma is unilateral and intramuscular.

- •

Type 2: The hematoma is intramuscular, as it is in type 1, but blood is also present between the muscle and the transversalis fascia. It may be unilateral or bilateral. No blood is seen in the prevesical space.

- •

Type 3: The hematoma may or may not affect the muscle; blood products are seen between the muscle and the fascia transversalis, as well as in the prevesical space.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

MRI is very useful in the diagnosis of abdominal wall hematoma, especially when the CT findings are nonspecific. Acute hematomas appear isointense relative to muscle on T1-weighted images and hypointense on T2-weighted images. Subacute hematomas demonstrate high signal intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted images.

Ultrasonography.

Hematomas appear as a nonspecific complex fluid collection with internal echoes and septations.

Imaging Algorithm.

Ultrasonography is the mainstay for diagnosis of suspected abdominal wall hematoma; however, in obese or postoperative patients, in whom ultrasound evaluation is limited, MDCT should be considered (see Table 83-1 ). In the acute setting, MDCT provides key information regarding hematoma size and extension into the abdominal cavity.

- •

Hematomas appear as heterogeneous fluid collections. Rectus sheath hematomas occurring above the arcuate line are contained within the muscular fascia. Below the arcuate line, hematoma may extend into the prevesical space, becoming uncontained ( Figure 83-9 ).

Figure 83-9

Abdominal wall hematoma. Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography image of the abdomen demonstrates a hematoma in the anterior abdominal wall in a 32-year-old woman after cesarean section. The hematoma is below the arcuate line, demonstrates hematocrit effect (asterisks), and is associated with extraperitoneal extension of the hematoma into the space of Retzius (arrowheads).

- •

CT and MRI show a heterogeneous fluid collection with fluid/fluid levels (hematocrit effect).

- •

Ultrasonography demonstrates a complex collection.

Differential Diagnosis

Abdominal wall hematoma may mimic other pathologic processes leading to acute abdomen. It may be confused with other fluid collections, such as infected or uninfected seroma ( Figure 83-10 ) or abscesses.

Treatment

In hemodynamically stable conditions, conservative measures are the mainstay of treatment. If the patient becomes unstable or cannot be controlled with conservative measures, surgical intervention or transcatheter embolization may be considered.

Endometriomas

Etiology

Endometriomas form when functional endometrial tissue is located outside the uterine cavity. This may occur after surgical procedures that disrupt the uterine cavity (e.g., cesarean section), allowing endometrial tissue to be seeding. In these cases, endometriomas may be located within the abdominal wall at the site of the surgical incision.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

In most cases, ectopic endometrial tissue is located within the pelvis, associated with the ovaries, uterine ligaments, and pelvic peritoneal folds.

Clinical Presentation

Most patients present with a palpable mass in the region of a surgical scar. A history of cyclic pain associated with menses may be present.

Pathophysiology

Two leading theories exist for endometriosis. One hypothesis suggests that mesenchymal cells with multipotential properties may undergo metaplasia into endometriosis. The other theory states that endometrial cells may be transported to ectopic sites, forming an endometrioma. When these cells are stimulated by estrogens, they may proliferate and become symptomatic.

Pathology

Extrapelvic endometriosis has been described in nearly all body cavities and organs, but the abdominal wall is the most frequent location, occurring in approximately 0.8% of patients with endometriosis.

Imaging

The ultrasound, CT, and MRI features of abdominal wall endometriosis are nonspecific. Endometriomas appear as a solid mass in the abdominal wall with hypervascular component.

Computed Tomography.

The major role of CT is to demonstrate a solid, enhancing mass in the abdominal wall.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

MRI may show high signal intensity on T1- and T2-weighted images resulting from hemorrhage. Nevertheless, abdominal wall endometrioma may be nonspecific—hypointense or isointense to muscle on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images and enhance after contrast administration.

Ultrasonography.

On ultrasonography, endometriomas tend to be solid, hypoechoic lesions within the abdominal wall; they show internal vascularity on Doppler studies. Cystic changes may occur and are probably secondary to intralesional bleeding during menstruation.

Imaging Algorithm.

Ultrasonography is the primary modality in the evaluation of abdominal wall masses (see Table 83-1 ). Because of its nonspecific solid appearance, additional imaging with MDCT or MRI is important to confirm local extent. Image-guided biopsy should be considered to exclude malignancy.

- •

A nonspecific, solid hypervascular mass is located within the abdominal wall.

- •

Presentation tends to be at the surgical incision site after pelvic surgery.

- •

Appearance on MDCT and MRI is similar to that of soft tissue tumors; thus, histologic assessment is usually necessary.

Differential Diagnosis

Imaging findings of abdominal wall endometrioma are nonspecific, and a wide spectrum of disorders should be considered in the differential diagnosis, including neoplasms (e.g., sarcoma, desmoid tumor, lymphoma, or metastasis) and non-neoplastic causes (e.g., suture granuloma, ventral hernia, hematoma, or abscess).

Treatment

Pharmacologic therapies with hormonal agents such as progestogens are indicated. If medical treatment of abdominal wall endometriosis fails, surgical excision is the treatment of choice.

Varices

Etiology

Abdominal wall varices are dilated subcutaneous veins that form part of a portosystemic shunt secondary to portal hypertension.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

In the setting of chronic liver disease, varices are common, occurring in up to 20% to 35% of patients.

Clinical Presentation

Abdominal wall varices are mainly asymptomatic.

Pathophysiology

Cirrhosis is the most common cause of intrahepatic portal hypertension and accounts for the majority of cases of portal hypertension in the West. Postsinusoidal and posthepatic causes of portal hypertension include portal and splenic vein thrombosis or hepatic diseases, Budd-Chiari syndrome, and inferior vena cava obstruction.

Pathology

The left portal vein communicates with the systemic epigastric veins near the umbilicus via paraumbilical venous channels (Cruveilhier-Baumgarten syndrome).

Imaging

Varices are easily identified on cross-sectional imaging modalities. They are located in the subcutaneous tissue or wall musculature and have a characteristic tubular shape ( Figure 83-11 ).

Computed Tomography.

Abdominal wall varices appear as subcutaneous, enhancing tubular structures near the umbilicus.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

Varices have a similar appearance on MR images as they do on CT scans.

Ultrasonography.

On Doppler ultrasonography, abdominal wall varices appear as fluid-filled dilated tubular structures, with intraluminal venous flow near the umbilicus.

Nuclear Medicine.

Abdominal varices result in pooling of technetium-99m–tagged red blood cells within the dilated vessels. Radiotracer localization may mimic scintigraphic findings of acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Clinical suspicion and careful evaluation of scintigraphic gastrointestinal bleeding studies will avoid false-positive interpretations.

Imaging Algorithm.

Ultrasonography is the mainstay for diagnosis of abdominal wall masses, including varices; however, if ultrasound evaluation is limited, MDCT or MRI should be considered (see Table 83-1 ).

- •

Dilated tubular structures, located within the abdominal wall, demonstrate slow flow on Doppler ultrasonography.

- •

Slow filling, with delayed enhancement after administration of a contrast agent, can be seen.

Differential Diagnosis

Abdominal wall varices may simulate hernias, abdominal wall tumors, or excessive scarring after previous surgery ( Figure 83-12 ).

Treatment

Abdominal wall varices are incidental findings and generally do not require medical treatment; however, these varices may bleed and require surgical ligation.

Pseudoaneurysms

Etiology

Pseudoaneurysms arise from disruption to the arterial wall, resulting from inflammation, trauma, or iatrogenic causes such as surgical procedures, percutaneous biopsy, or drainage.

A pseudoaneurysm is a pulsatile hematoma in the soft tissues with persistent communication between the artery and the extraluminal space.

Pathophysiology

A pseudoaneurysm lacks endothelial lining and differs from a hematoma in that it has direct communication with the arterial lumen.

Pathology

Pseudoaneurysms predominantly involve the common femoral artery and usually manifest within 2 cm of the arterial puncture site.

Imaging

Femoral artery pseudoaneurysm causes a localized groin mass with heterogeneous appearance on unenhanced images due to blood products communicating with the arterial lumen.

Radiography.

Angiography remains the standard of reference for the diagnosis of pseudoaneurysms despite the advent of new imaging technologies.

Computed Tomography.

Contrast-enhanced CT and CT angiography show a contrast-filled sac. A low-attenuation area within the pseudoaneurysm indicates partial thrombosis. The donor artery adjacent to the pseudoaneurysm can usually be seen communicating with it.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

On MRI, pseudoaneurysms have an appearance similar to that on CT. MR angiography is a valuable tool assessing pseudoaneurysms in patients with allergy to iodinated contrast agents.

Ultrasonography.

A pseudoaneurysm is a cystic structure that typically demonstrates direct communication with the arterial lumen. Swirling of echogenic blood may be seen within the pseudoaneurysm cavity on real-time examination. On Doppler examination, arterial flow is seen within the pseudoaneurysm. To-and-fro flow between the artery and the pseudoaneurysm also is usually evident.

Imaging Algorithm.

Ultrasonography is the mainstay for detection and visualization of pseudoaneurysms and associated hematoma (see Table 83-1 ). Moreover, it permits evaluation of the neck and lumen of the pseudoaneurysm; and, in most cases, ultrasound-guided compression results in complete thrombosis of the pseudoaneurysm. For cases in which additional information is needed, MDCT and/or MRI may be performed.

- •

Pseudoaneurysm is a contained vascular perforation.

- •

On contrast-enhanced studies, pseudoaneurysms show contained contrast extravasation, with a neck (pseudoaneurysm inlet) at the site of vessel perforation.

Differential Diagnosis

A hematoma or any inflammatory or neoplastic process may produce a groin mass and local mass effect.

Treatment

Medical Treatment.

Ultrasound-guided percutaneous injection of thrombin is an alternative procedure that many authors suggest as the therapeutic method of choice. Technical success rates with this method in the setting of postcatheterization pseudoaneurysms are greater than 90%.

Surgical Treatment.

Endovascular management permits exclusion of pseudoaneurysms from the circulation and includes two broad categories: embolization and stent placement.

Neoplastic Conditions

Etiology

Both primary and secondary neoplasms of the abdominal wall are relatively uncommon. Benign primary tumors include lipoma, neuroma, neurofibroma, and desmoid tumor, which do not typically metastasize but can be locally aggressive. Malignant primary tumors include the spectrum of soft tissue sarcomas. Metastases to the abdominal wall are more common than primary malignancy, and periumbilical involvement may occur secondary to intraperitoneal spread.

Prevalence and Epidemiology

Abdominal wall neoplasms are rare, accounting for less than 2% of adult malignant tumors. Some subcutaneous lesions may be a manifestation of systemic disease, such as neurofibromas in neurofibromatosis or lipomas in lipomatosis.

The most common primary neoplasm of the abdominal wall is a desmoid tumor, a benign entity with aggressive local behavior. Primary malignant lesions, most commonly sarcomas, occur infrequently and metastatic melanoma is the most frequent secondary malignancy.

Clinical Presentation

Although large masses are generally discovered by inspection and palpation, small tumors may be difficult to detect clinically, particularly in obese patients or in those with surgical scars or indurated tissue.

Pathophysiology

Malignant primary tumors tend to originate from connective tissues of the abdominal wall, whereas metastases tend to involve subcutaneous tissue but may occur in any compartment of the abdominal wall.

Pathology

Pathologic findings vary greatly, according to the specific type of neoplasm.

Imaging

Computed Tomography

MDCT is the mainstay of diagnostic imaging to assess patients with suspected abdominal wall lesions owing to its widespread availability, excellent spatial resolution, and relative lack of susceptibility to motion artifact. Multiplanar and three-dimensional CT reformatted images provide excellent anatomic assessment of these lesions, which is useful when planning operative intervention.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Because of its superior soft tissue contrast, MRI provides important information regarding tumor extension and is particularly useful to facilitate accurate preoperative local staging and surgical planning.

Ultrasonography

Although ultrasonography is highly operator dependent, it is relatively inexpensive, noninvasive, and widely available, playing an important role in the evaluation of patients with suspected abdominal wall masses.

Ultrasonography provides important information regarding lesion location and extent and may be used for percutaneous image-guided biopsy or percutaneous treatment. The primary limitation of ultrasonography is that it does not demonstrate deep extension of large abdominal wall lesions and may not accurately delineate the relationship of these lesions to underlying bowel.

Positron Emission Tomography With Computed Tomography

Positron emission tomography with CT (PET/CT) is recommended for staging metastatic disease. Abdominal wall metastases shows avid uptake of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), allowing differentiation from benign nodules. FDG uptake of soft tissue sarcomas is variable, and thus the role of PET/CT in this setting is limited.

Imaging Algorithm

The most useful diagnostic imaging techniques for suspected abdominal wall tumors are MDCT, MRI, and ultrasonography, all of which show high anatomic detail, tumor location, and local extension ( Table 83-2 ).

| Modality | Accuracy | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Radiography | Limited availability of source literature for comparing accuracy of different imaging modalities for detecting abdominal wall neoplastic lesions | Not useful for small lesions |

| CT | Ionizing radiation | |

| MRI | Expensive and not widely available Limited on postoperative patients Patient-limiting factors (e.g., claustrophobia, pacemaker) | |

| Ultrasonography | Obesity, significant scarring, patients with acute abdominal pain Operator dependent | |

| PET/CT | Most wall metastases demonstrate avid FDG uptake. Benign primary lesions do not show FDG uptake. |

Ultrasonography may be used as the primary imaging modality in patients with suspected abdominal wall lesions. MDCT and MRI are particularly useful to assess local extension and involvement of intra-abdominal structures.

Imaging of Specific Lesions

Benign Abdominal Wall Tumors.

Benign abdominal wall tumors are frequent incidental findings on abdominal imaging. This category includes lipoma, neuroma, neurofibroma, and other less common tumors, such as hemangioma and lymphangioma.

Lipomas may manifest in the subcutaneous tissue or in the muscular planes. When there is a soft tissue component or an increase in size, malignant degeneration (liposarcoma) should be suspected.

Neurofibromas occur most frequently in patients with neurofibromatosis, manifesting as multiple, small, and well-defined lesions in the subcutaneous tissue of the abdominal wall ( Figure 83-13 ).