Abstract

Neurointerventional radiology has many applications in the skull base. We focus on preoperative embolization to hypervascular tumors and embolization of the vascular lesion, in a hope to keep in-depth discussion. The former section discusses preoperative embolization to hypervascular tumours. The goals of the preoperative embolization are to devascularize the tumour vessel and to decrease surgical blood loss. The basic principle is emphasized in this part. Dangerous intracranial-extracranial collateral, in terms of functional anatomy, is introduced. Embolic agents and embolization methods are comprehensively discussed. Illustrations with the juvenile angiofibroma and paraganglioma are presented. In the section on vascular lesions, we discuss the dural arteriovenous fistula and carotid cavernous fistula. The goal of embolization treatment is usually disease cure or alteration of natural history. The pathophysiology, classification, and clinical presentations of the entities are briefly reviewed. Embolization approaches and common techniques are discussed with updated evidence. Other issues, including postprocedural care and alternative treatments, are also covered in this section.

Keywords

Carotid cavernous fistula, Dural arteriovenous fistula, Embolization, Juvenile angiofibroma, Paraganglioma

In this chapter, we discuss the embolization of the most common hypervascular tumors and vascular lesions occurring at the skull base (i.e., the juvenile angiofibromas [JAFs], paragangliomas [PGLs], dural arteriovenous fistula [DAVF], and traumatic carotid-cavernous fistula [CCF]). Other rare diseases such as orbital arteriovenous malformation and aneurysm at the foramen magnum are not included. We provide an introduction to the pathogenesis of these diseases, the current methods of embolization, outcome assessment, and the controversies relating to the clinical management of these diseases.

Embolization of Hypervascular Tumors Located at the Skull Base

The most common hypervascular tumors arising at the skull base are JAF and PGL (glomus tumor). Less common tumors include meningioma, hypervascular metastases, hemangiomas, and endolymphatic sac tumors. Preoperative embolization is considered to be a relatively safe, minimally invasive, supplementary procedure. In the following sections, we discuss the goal of treatment, the functional anatomy, embolic materials, and methods of embolization and provide some details about the embolization of JAF and skull base glomus tumor.

Goals of Preoperative Embolization

The main goals of preoperative embolization of hypervascular tumors in the skull base are to shorten the operation time and decrease the intraoperative blood loss by obliterating the capillary bed and the proximal feeding arteries. Other goals are to improve exposure of the tumor, enable a more radical removal of the tumor, and decrease recurrence rate. In comparing blood loss without and with preoperative embolization, one report found that blood loss was reduced from 750 to 400 mL on average, but no cases with intracranial extension were included in this assessment. Others reported the mean intraoperative blood loss in patients with embolized tumors to be 770 mL compared with 1500 mL in patients with nonembolized tumors. We can speculate that a successful preoperative embolization could cut intraoperative blood loss in half.

Preoperative devascularization decreased recurrence rates from 11% to 7% and increased the absolute relapse-free rate from 56% to 73% in patients with JAF. However, the contribution of preoperative arterial embolization to lowering JAF recurrence rates has been questioned.

Functional Anatomy

The anatomy of vascular structures at the skull base is complex and variable. Most skull base structures draw their blood supply from the external carotid artery (ECA), but skull base tumors commonly receive blood from the internal carotid artery (ICA) and vertebral artery (VA), especially when the tumors extend intracranially. The extent of vascular anastomosis between the extracranial and intracranial vasculatures is another important issue to consider when selecting patients with skull base tumors for embolization. Dangerous anastomosis may exist between the ECA, ICA, VA, ophthalmic artery, ascending cervical artery, deep cervical artery, and spinal arteries. Box 17.1 summarizes these dangerous anastomoses.

- 1.

Anterior or ophthalmic artery connections with facial and internal maxillary arteries;

- 2.

Middle or petrocavernous internal carotid artery branches with internal maxillary and ascending pharyngeal branches;

- 3.

Posterior or VB (Vertebrobasilar) connections with ascending pharyngeal, occipital, and subclavian artery branches, especially the ascending and deep cervical arteries.

These dangerous anastomoses may not be revealed by preembolization diagnostic angiography and may appear suddenly as a result of the Venturi effect after partial embolization. Cerebral stroke is one of the major complications of embolization for skull base lesions and can occur when embolic material travels into the VA or ICA territories via existing anastomoses. Another concern during embolization of the skull base tumor is the blood supply to cranial nerves. Valavanis proposed the concept of “dangerous” and “safe” vessels for embolization. Arteries not supplying a cranial nerve were regarded as “safe,” whereas arteries feeding a functional nerve were termed “dangerous.” The caliber of the tiny vasa nervorum is usually less than 60 μm. Devascularization of the vasa nervorum (a region of dangerous vessels) might cause cranial nerve palsy during embolization of the skull base tumor. To deal with dangerous vessels supplying both the tumor and cranial nerve, we have to use larger particles (>150 μm) and avoid liquid embolic agents.

Embolic Materials

Embolic materials can be categorized as particles and liquids. See Box 17.2 .

Particles

Gelform

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)

Tris-acryl gelatin (Embospheres)

Polyzene-F hydrogel (Embozenes)

Liquid

n-Butyl cyanoacrylate (NBCA)

Ethylene vinyl alcohol copolymer (Onyx) (SQUID)

Particulate Embolic Materials

Many different particles have been used for tumor embolization, and their further subdivision into polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), tris-acryl gelatin (embospheres), and polyzene F-coated hydrogel (embozenes) is based on the composition of the microsphere polymer matrix. PVA microspheres can be further subdivided into nonspherical PVA, spherical PVA, and acrylamido PVA.

The catheters required to inject these particles must have a larger inner diameter and be stiffer than those used for the delivery of liquid embolic agents. Catheters are wire guided and more difficult and hazardous to navigate through distal friable vessels than flow-guided catheters. All these restrictions make it difficult to optimize the particle size of embolic agents used to penetrate the capillary bed of the tumor without occluding the arterial pedicle or passing through the nidus into the venous system.

The size of the particles is important. Larger particle size (more than 150 μm) is believed to enable the efficient penetration of the tumor’s capillary bed. Meanwhile, particle size more than 150 μm is also safe in cases of dangerous vessel embolization. The same is true for tris-acryl gelatin and polyzene-F hydrogel microspheres.

Tris-acryl gelatin and polyzene-F hydrogel microspheres do not aggregate and tend to lodge in vessels that are close in size to the particle diameter, and blood does not flow beyond the embolized region. They are less likely to clump and clog the microcatheter. By contrast, PVA particles aggregate in vessels larger than the particle’s diameter, preventing blood flow into regions peripheral to the embolized region. However, both methods produce only temporary occlusion. Therefore, no more than 7 days between particle embolization and surgery is critical to ensure sufficient devascularization. Seemingly, tris-acryl gelatin and polyzene-F hydrogel are superior to PVA for tumor penetration to achieve embolization. But one meta-analysis assessing five widely used embolic particles (three types of PVA particles, tris-acryl gelatin, and polyzene-F hydrogel) in uterine fibroid embolization found no evidence of the superiority of any embolic agent.

Liquid Embolic Materials

The two most widely used and most effective agents for embolizing vascular lesions are polymers: n-butyl cyanoacrylate (NBCA [Histoacryl], Braun, Melsungen, Germany, and Trufill, Cordis Neurovascular, Miami, FL) and ethylene-vinyl alcohol (EVA) (Onyx; EV3 Neurovascular, Irvine, CA) dissolved in the solvent base dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Like Onyx, SQUID (Emboflu, Fribourg, Switzerland) is also an EVA dissolved in DMSO but it is available in different concentrations: 4.9% and 6.0%. Micronized tantalum powder is added to both Onyx and SQUID to provide radiopaque contrast. Both Onyx and SQUID must be vortexed (Vortex-Genie, Scientific Industries, Bohemia, NY) at least 20 min to ensure stable mixing of the tantalum with the polymer.

NBCA is a liquid monomer that polymerizes into an adhesive when in contact with an anionic solution (i.e., blood). It is radiolucent but becomes radiopaque when mixed with agents such as Lipiodol (Lipiodol Ultra Fluide, Guerbet, Solingen, France), Ethiodol (Savage Laboratories, Melville, NY), or Tantalum powder (American Elements, Los Angeles, CA). A small, flexible microcatheter is safely and gently navigated into the capillary bed of the tumor for NBCA delivery. A significant level of experience is needed to deliver NBCA appropriately. It is difficult to control the polymerization time of NBCA. In our institution, we usually mix NBCA with Lipiodol in a ratio of 1:2 to 1:3 to slow polymerization. The relationship between the NBCA to Lipiodol ratio and polymerization time is not linear. Gluing the microcatheter to the vessel wall is another risk. Delayed migration of the polymerized glue into the intracranial circulation 12 h after NBCA embolization has also been reported.

The benefits of Onyx over NBCA have been well described. Onyx polymerizes after contact with blood or any aqueous solution and with diffusion of the solvent DMSO. Onyx forms a spongy surface layer but remains liquid at its center. This characteristic causes it to flow like lava within blood vessels and to form a nonadherent plug without fragmentation during injection. During the Onyx injection, the operator can interrupt the procedure several times to allow assessment of the outcome of embolization and early recognition of dangerous intracranial anastomoses. SQUID (another EVA copolymer dissolved in DMSO polymer) has become available in Europe. It is less viscous (which facilitates vascular penetration), less dense, and contains 30% less tantalum, all of which may help visualize structures behind dense embolic casts under X-ray. The micronized tantalum particles in SQUID are smaller than those in Onyx and allegedly are dispersed into a more homogeneous suspension. SQUID has been successfully used for embolization of tumors without any complication.

Particulate embolic agents are usually cheaper than liquid agents, but they have several disadvantages. The particles are radiolucent and require the addition of a contrast agent to indirectly determine the extent of tumor embolization. This adds to the embolic load, which should be a consideration when carrying out the procedure in young patients. The particles (especially PVA) tend to aggregate in and clog the microcatheters, necessitating recatheterization of the feeding arteries; this makes particulate embolization more time consuming than liquid embolization. The devascularization effect of particulate embolization is temporary, and tumor resection should be performed within 7 days.

During surgical or endoscopic procedures, it is often very difficult to distinguish tumor tissue from the surrounding tissue. Onyx provides an additional advantage in that tumor tissue is readily distinguishable both visually and under X-ray examination, making it possible to determine intraoperatively whether residual tumor tissue exists and where it is located. The clear demarcation by Onyx of the tumor from its surroundings allows for complete tumor removal and may account for the much lower recurrence rates associated with Onyx use for embolization.

Onyx and NBCA are associated with similar complications. However, Onyx use is also associated with trigeminocardiac reflex, a rare complication defined as the sudden onset of parasympathetic dysrhythmia, sympathetic hypotension, apnea, or gastric hypermotility during stimulation of any of the sensory branches of the trigeminal nerve. Because Onyx use is more expensive and more time consuming than NBCA use, it should be reserved for selective cases.

Methods of Embolization

Transarterial Embolization

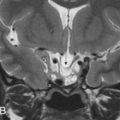

Skull base tumors are often devascularized under general anesthesia. Some institutions monitor neurophysiologic activity (electroencephalography, somatosensory evoked potentials, and brainstem auditory evoked potentials) and maintain activated clotting times between 250 and 300 s during the procedure. At our institution, we maneuver a 6Fr Envoy (Cordis; Miami Lakes, FL) guide catheter or 4Fr diagnostic catheter of 100 cm length (Vertebral, Glide catheter; Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) into the appropriate ECA and selectively catheterize the feeding vessels with either an SL-10 microcatheter (Stryker Neurovascular, Fremont, CA) or a 2.9F microcatheter (Progreat, Terumo) using the coaxial technique. Selective angiograms of those feeder arteries are performed to assess the portion of the tumor supplied by the artery, the degree of tumor pedicle vascularity, and the location of potentially dangerous extracranial/intracranial anastomoses ( Fig. 17.1 ).

Particulate embolization of skull base tumors is performed by placing the microcatheter tip as close to the capillary bed of the tumor as possible under fluoroscopic guidance. The antegrade flow in the feeders carries the particles to the target tumor. We prefer to start with particles about 150–250 μm in diameter to penetrate the capillary bed of the tumor and then introduce particles 250–350 μm in diameter till contrast medium stasis is observed in the feeders ( Fig. 17.2 ). Transarterial particulate embolization is performed under continuous fluoroscopic guidance until nearly complete stasis of the blood flow within each feeding pedicle is achieved. In some centers, nitroglycerine is administered intraarterially to prevent arterial spasm and to promote appropriate forward flow of particles. Many authors prefer to block the main trunk with gelfoam pledgets (Gelfoam, Upjohn, Kalamazoo, MI) or platinum microcoils (Target Therapeutics, Fremont, CA) after obtaining cessation of flow. Sometimes, we use microcoils to occlude the branches supplying normal tissue to decrease the risk of damage to the normal tissue.

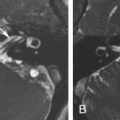

During NBCA embolization, the NBCA and Lipiodol are mixed in an appropriate ratio based on the flow dynamics and micro-angio-architecture depicted on the angiogram. The catheter is then prepared by flushing with 5% dextrose water. The NBCA-Lipiodol mixture is then injected slowly under guidance using a single-column method. Injection is stopped immediately if reflux or flow into dangerous vessels is found. After withdrawal under moderate negative pressure, the micro- and guide catheters are rapidly pulled away from the site of injection to prevent them from being glued in place. The technique is repeated as many times as necessary to achieve maximal devascularization of the neoplasm. Before the NBCA-Lipiodol injection for brain arteriovenous malformations, some authors prefer to have the patient under moderate hypotension or ask the anesthesiologist to apply a Valsalva maneuver to the patient during the injection because this increases venous pressure, preventing or reducing the movement of the NBCA-Lipiodol mixture into the draining vein. We do not use this maneuver during devascularization of skull base tumors. The short polymerization time of NBCA limits the amount of embolic injected and always requires multiple injections. The injection of NBCA cannot be halted during the procedure to allow assessment of the degree of embolization and early recognition of dangerous anastomoses ( Fig. 17.3 ).

Onyx polymerizes after contact with blood or any aqueous solution and with diffusion of the solvent DMSO. Compared with NBCA, Onyx is more easily controlled. However, all DMSO-compatible microcatheters are stiffer than the microcatheters used for injection of other agents, and DMSO can cause angionecrosis and vasospasm. Before injection, Onyx must be mixed for at least 20 min. Otherwise, visualization of the Onyx during injection could be suboptimal and sedimentation of the tantalum powder could block the microcatheter hub or shaft.

Onyx is available in two concentrations and viscosities: Onyx-18, with a polymer to solvent ratio of 6% and a viscosity of 18 cP and Onyx-34, with a polymer to solvent ratio of 8% and a viscosity of 34 cP. The impact of viscosity on intraparenchymal penetration is theoretically an important consideration. In devascularization of skull base tumors, Onyx-18 is preferred.

Before embolization, removal of microcatheter redundancy should be done under fluoroscopic guidance. The contrast material in the microcatheter is cleared by flushing with saline. Then, DMSO is injected into the catheter to fill dead space in the microcatheter. Onyx injection is conducted under blank road map fluoroscopy over a 90-s period to replace the DMSO in the dead space, thereby eliminating the angionecrotic potential of DMSO. Onyx infusion is stopped when reflux around the catheter tip is detected. After several minutes, a new blank road map is created and injection is resumed. Ideally, antegrade flow is reestablished, and the Onyx enters other compartments. This procedure (the plug and push technique) is repeated until the desired effect is obtained or a normal branching vessel can be occluded. After multiple rounds of injection, reflux, and waiting, the reflux may extend 1.0–1.5 cm from the tip of the microcatheter. Finally a plug may form around the tip completely blocking blood flow and changing pressure gradients within the tumor’s capillary bed until Onyx penetrates the tumor more deeply. Unlike NBCA, Onyx requires that the microcatheter be pulled straight before retracting it with gradually increased force and then either snapping it out of the Onyx cast or slowly pulling it out. We use postembolization ECA angiograms to assess the degree of devascularization.

Embolization by Direct Puncture

Many centers suggest direct intratumoral puncture as the first-choice devascularization technique for head and neck tumors. In our institution, the rationale for using direct puncture for skull base tumor devascularization is reserved for the following conditions: impossible superselective catheterization of the feeding arteries because of their small size and tortuosity, high possibility of reflux into a dangerous intracranial anastomosis, and persistence of leakage after transarterial embolization. Using the transarterial approach, optimal intraparenchymal tumor penetration with liquid agents is difficult to achieve unless the microcatheter is situated within 2 cm of the tumor.

A single dose of preoperative antibiotics is administered because of the theoretical but low risk of infection from oral or nasal flora. A detailed angiographic evaluation of the degree of lesion is obtained, and the tumor extent is confirmed by CT or MR examination. Depending on the location of the tumor and the important adjacent neurovascular structures, needles can be placed directly into the tumor via the transzygomatic, transnasal, transoral, transbuccal, transpalatal, transorbital, or percutaneous route. Which approach is selected depends on proximity to the tumor and appropriate margins needed to protect vital neurovascular structures. An 18- or 20-gauge needle is used to puncture the tumor under angiographic and fluoroscopic guidance and subsequently advanced to the center of the lesion under fluoroscopic road map guidance. An intratumoral angiogram is performed to confirm the position of the needle within the tumor, assess the microvasculature of the tumor, determine the venous drainage pattern, and identify dangerous intracranial anastomoses. Then the hub of the puncture needle is connected to a 10-cm Luer Lock extension tube. The dead space is slowly filled with DMSO (when Onyx is the embolic agent) or 5% dextrose water (when NBCA is the embolic agent) using a 1-mL Luer Lock syringe as needed. Embolization of the tumor is performed under subtracted road map guidance. In large heavily vascularized tumors, the needle can be redirected under road map guidance to a different compartment of the tumor to allow a more thorough penetration of embolic agents. Intermittent ECA and ICA angiography is needed to assess the degree of devascularization and detect hemodynamic changes such as recruitment of short arterial feeders from the ICA or VA after partial embolization. If this happens, placement of a temporal balloon at the origin of these arteries in the ICA or VA may theoretically be helpful in preventing nontarget embolization during further intratumoral injection of a liquid embolic agent. However, this increases the complexity of the procedure and may subject the patient to the additional risk of dissection or a thromboembolic event. Feeders from the ophthalmic artery are a relative contraindication for direct puncture embolization with a liquid embolic agent. Embolization is continued until the desired degree of tumor penetration is achieved.

Complications

Regardless of the method or materials used in the devascularization of skull base tumors, the most common complication is migration of the embolic agent to the ophthalmic artery or intracranial system. Inadvertent ocular embolization of the central retinal artery occurs via the middle meningeal artery in up to 3% of the population not identified by the preembolization study. This can also happen when embolization of the recurrent meningeal artery, meningoophthalmic trunk, and normal vessel variants is performed. Besides the common intracranial-extracranial anastomoses mentioned earlier, arteries such as the deep temporal, infraorbital, sphenopalatine, greater palatine, and ascending pharyngeal arteries and artery of the vidian canal have the potential for forming intracranial-extracranial anastomotic collateral networks and may be the culprit vessels involved in cerebral stroke occurrence after extracranial embolization.

Juvenile Angiofibroma

JAFs account for approximately 0.05% of all head and neck neoplasms. Surgical removal is widely accepted as the primary mode of JAF therapy. JAFs are highly vascular lesions, and their excision is frequently accompanied by significant intraoperative blood loss. Preoperative tumor devascularization is a supplementary treatment to minimize intraoperative blood loss. All the treatments mentioned in the earlier sections can be applied to JAFs.

The blood supplied to JAFs is usually from internal maxillary artery branches, such as the sphenopalatine arteries, anterior ascending pharyngeal artery, and accessory meningeal artery. As the tumor grows, it receives blood from facial artery branches such as the ascending palatine artery, ethmoidal branches of the ophthalmic artery, and ICA branches, such as the mandibulovidian/pterygovaginal artery, inferolateral trunk, meningohypophyseal trunk, and other petrous ICA segment branches. JAF blood supply is often bilateral (in up to 30%–40% of cases).

During surgery, the flow through the sphenopalatine artery is considered to be the source of profuse bleeding during removal of the tumor ( Fig. 17.3 ). Preoperative occlusion of this artery can thus shorten the operative time, increase the safety of the operation, and help reduce the total perioperative blood loss.

Many classifications have been proposed for the staging of JAFs. A detailed discussion of these classifications is not within the scope of this chapter. Yet they are used for surgical planning and treatment. A concise easier-to-use staging system for deciding whether to perform devascularization in JAF (see Box 17.3 ) was proposed by Yi et al. We propose that transarterial embolization (particles or liquid) can be used to devascularize type I lesions and direct puncture and/or the transarterial approach may be needed for type II lesions. In type III lesions, both the transarterial and direct puncture approaches are associated with a high risk of bleeding from the ICA and its branches and also from preexisting intracranial-extracranial anastomotic collaterals.

Type I: JAFs fundamentally localized to the nasal cavity, paranasal sinus, nasopharynx, or pterygopalatine fossa.

Type II: JAF extending into the infratemporal fossa, cheek region, or orbital cavity, with anterior and/or minimal middle cranial fossa extension but intact dura mater.

Type III: Calabash-like massive tumor lobe in the middle cranial fossa.

In comparison with the transarterial approach, direct puncture is associated with a shorter operation time. But current studies did not have sufficient power to show a statistically significant difference in estimated blood loss during subsequent tumor resection between the two methods. Careful embolization via either direct tumor injection or a transarterial route is safe and effective in presurgical management of JAFs. Occasionally, direct percutaneous embolization with liquid agents in conjunction with standard endovascular embolization techniques may be a good alternative.

Tympanojugular Paragangliomas

Head and neck PGLs are rare tumors, and they are classified by the sites of origin as carotid body tumors (at the bifurcation of the common carotid artery); jugular PGLs (close to the jugular bulb) and tympanic PGLs (in the middle ear), usually considered together (tympanojugular PGLs, TJPGLs); and vagal PGLs (along the vagus nerve). In a large reported series of 204 PGLs, 57% were carotid body tumors and 30% were TJPGLs. PGLs have their origin in the paraganglia of the chemoreceptor system. TJPGLs arise from a small group of cells in the adventitia of the jugular bulb.

The natural history of PGLs is variable. Approximately 38%–60% of PGLs are slow growing, with the tumor’s doubling time varying widely (0.6–21.5 years; mean growth range 0.2–1 mm/year). In a study of 47 patients with PGL, 42% had stable tumors and 20% had tumors that decreased in size.

Despite their benign origin, TJPGLs are locally aggressive, destructive neoplastic lesions and frequently invade the middle ear, temporal bone, and upper neck, with extension through the jugular foramen into the posterior cranial fossa. Based on their location, size, and extent, they have been classified by Fisch into four categories (see Box 17.4 ).

Class A tumors are located along the tympanic plexus on the promontory

Class B tumors invade the hypotympanum but do not erode the jugular bulb

Class C tumors

C1 tumors destruction of the jugular bulb/foramen

C2 tumors invasion of the vertical carotid canal

C3 tumors invasion of the horizontal carotid canal

C4 tumors invasion of the cavernous sinus

Class D: Besides the various degrees of invasion described for class C, intracranial extradural or intradural extension occurs

De1 intracranial and extradural invasion of up to 2 cm

De2 intracranial and extradural invasion of more than 2 cm

Di1 intracranial and intradural extension of up to 2 cm

Di2 intracranial and intradural extension of between 2 and 4 cm

Di3 intracranial and intradural extension of more than 4 cm

Optimal management is multifactorial and highly dependent on the tumor (location, size, involvement of neurovascular structures, malignancy, and hormone production), the patient (age, comorbidities, and symptoms), and the genetic status (implying potential for recurrence, malignancy, or multicentric tumors). Treatment of TJPGL remains controversial. Observation alone has been recommended, especially in the elderly and/or asymptomatic patients. The main treatment modalities for TJPGL include surgery and radiotherapy. Overall, gross total resection is achievable in 78.2%–86% of the cases and is associated with a low surgical mortality rate (0%–2.7%), but the success rate is generally lower in Fisch C and D class TJPGLs, and it decreases to 41% in class D tumors or 35% if the tumors have a large intradural extension. Surgery is associated with hemorrhagic, cerebrovascular, and neurologic risks (paresis of the lower cranial nerves leading to swallowing and speech problems, aspiration, feeding tube or tracheostomy dependence, facial palsy, and hearing loss). The recurrence rate was 18.8% in one report with 112 months follow-up. Surgery for large TJPGLs is challenging because of their high vascularity and close relationship with delicate neurovascular structures. However, favorable long-term results can be achieved by involving a multidisciplinary team in the planning and execution of surgery. Radiosurgery as the primary treatment revealed high rates of tumor growth control and relatively low morbidity in a series. Owing to the relatively benign natural history of TJPGLs, a long follow-up duration is needed before a correct conclusion can be drawn about the efficacy of any treatment.

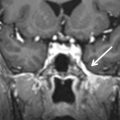

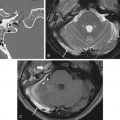

The primary arteries supplying blood to TJPGLs are the ascending pharyngeal artery, posterior auricular artery, and occipital artery ( Fig. 17.4 ). The clival meningeal branches of the carotid artery and the meningeal branches of the VA supply the intracranial component in patients with Fisch class D TJPGL, and the posterior inferior cerebellar artery and the anterior inferior cerebellar artery supply the posterior intradural TJPGLs. Preoperative embolization and interdisciplinary microsurgical resection of TJPGLs are the preferred treatment for selected patients because of their association with high tumor control rates and good long-term results. Preoperative embolization can dramatically reduce tumor vascularity, operative times, blood loss, and surgical complications.

In instances in which the ICA is encased, balloon occlusion is used to assess whether carotid sacrifice would be possible during surgery. An alternative to sacrifice of the ICA is preoperative stenting. This prevents the risk of the carotid rupture during surgery and obviates the need for balloon occlusion or bypass procedures.

However, the intimate anatomic relationship and overlapping blood supply between these tumors and cranial nerves (see Box 17.5 ) may contribute to a high incidence of cranial neuropathy (approximately 18%) after liquid agent embolization.

| Facial nerve | Petrosal branch of middle meningeal artery |

| Stylomastoid branch of postauricular artery or occipital artery | |

| Glossopharyngeal nerve, vagus nerve, and spinal accessory nerve | Jugular branch of neuromeningeal trunk of the ascending pharyngeal artery |

| Hypoglossal nerve | Hypoglossal branch of neuromeningeal trunk of the ascending pharyngeal artery |

Warren et al. reported that postoperative new cranial neuropathy occurred less frequently when preoperative TJPGL devascularization was carried out by a combination of two procedures (embolization of the inferior petrous sinus and transarterial embolization) than by transarterial embolization alone (38% vs. 80%). However, the materials used in these procedures and postembolization outcome were not reported. So, further investigation is warranted.

The recently reported use of dual-lumen balloon catheter injection for preoperative Onyx embolization of skull base PGLs in five patients showed promising results. However, this has not yet been confirmed in a large series, and we still consider that liquid agents pose a higher risk of permanent cranial neuropathy. A single embolization can be regarded as merely palliative owing to the high revascularization rate, although good short-term outcome has been reported in a small series. We consider embolization to be the sole treatment for recurrent or inoperable TJPGLs ( Fig. 17.5 ).

Embolization for Vascular Lesions in the Skull Base

In this section, we shall discuss the treatment of the two most common vascular lesions occurring in the skull base: DAVF and traumatic CCF.

Dural Arteriovenous Fistula

Intracranial DAVF is a disease in which blood flow from the meningeal artery is shunted directly into the cerebral drainage venous system in the dura or associated osseous structure. It is considered an acquired disease, accounts for 10%–15% of intracranial vascular anomalies, and can occur anywhere in the pachymeninges. Because intracranial DAVF varies in location and severity, it can vary in clinical manifestations and natural history. The pathophysiology is not yet completely understood, but cerebral venous thrombosis and hypertension may play an important role. Many conditions are associated with its occurrence, such as trauma and hypercoagulation. A common hypothesis is that DAVFs form in three stages. It begins with a thrombotic event in a compromised sinus, followed by formation of a fistula extending from the site of arterial occlusion to the vasa vasorum of the sinus wall, and ends with partial recanalization of the thrombosed segment, reflecting the complex nature of locoregional vasogenesis.

In more than 70% of cases, the disease occurs predominantly in the skull base region, including the cavernous sinus and transverse-sigmoid sinus. Other less frequent locations in the skull base include the anterior cranial base, superior sagittal sinus (SSS), tentorial incisura, hypoglossal canal, and foramen magnum, making it the most common neurovascular disease affecting the skull base.

Classification, clinical presentation, and diagnosis

Proper description of the disease is essential for subsequent management. A good way to describe these diseases is to separate them by location. This is still the most essential element of the classification of this entity. Subsequent classification systems added clinical implications, mainly based on natural history. There are many different classification systems for this disease. The effort began with Djinjian and Merland. Currently, the Cognard and Borden systems are the most popular and widely used. The three classification systems are listed in Table 17.1 . We suggest readers become familiar with all three. Cognard classified the disease into types I through V, with two subtypes IIa and IIb, representing retrograde sinus flow and retrograde flow into the cortical vein, respectively. Borden classified the disease into types I–III. Type II is equivalent to Cognard type IIb, and type III is equivalent to Cognard type III or IV. Both systems call attention to corticovenous reflux, which is associated with aggressive clinical presentation and outcome. Borden type I is considered benign, whereas type II and type III are considered aggressive. In a 7-year follow-up study, the aggressive type was associated with 8.1% of hemorrhagic events and 6.9% of nonhemorrhagic neurologic events.

| Djindian & Merland | Cognard | Borden | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type I | Drainage into a sinus or a meningeal vein | Type I | Antegrade drainage into a sinus or meningeal vein | Type I | Drainage directly into dural venous sinuses or meningeal veins |

| Type II | Sinus drainage with reflux into a vein discharging into the sinus | Type IIa | As type I but with retrograde flow | Type II | Drainage into dural sinuses or meningeal veins with retrograde drainage into subarachnoid veins |

| Type III | Drainage solely into cortical veins | Type IIb | Reflux into cortical veins | Type III | Drainage into subarachnoid veins without dural sinus or meningeal venous drainage |

| Type IV | With supra- or infratentorial venous lake | Type IIa + b | Reflux into both sinus and cortical veins | ||

| Type III | Direct cortical venous drainage without venous ectasia | ||||

| Type IV | Direct cortical venous drainage with venous ectasia | ||||

| Type V | Spinal venous drainage | ||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree