Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Todd M. Blodgett, MD

Alex Ryan, MD

Omar Almusa, MD

Key Facts

Terminology

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL)

NHL: Malignancy of B or T lymphocytes

Imaging Findings

Spleen involved in 20% of patients with NHL

Other extranodal lymphoma may arise in CNS, peripheral nervous system, lung and pleura, bone, skin, breast, testis, and GU tract

PET/CT: Use with contrast-enhanced CT for staging

Enlarged LN, extranodal mass with low to moderate FDG uptake

Enlarged/normal-sized FDG-avid nodes in liver or spleen; “misty mesentery”

PET excellent for predicting prognosis in aggressive NHL after therapy

Post-therapy evaluation

Absence of metabolic activity on FDG PET following treatment (high predictive value for disease-free survival)

Persistent metabolic activity on FDG PET following treatment (moderate predictive value for recurrence)

Top Differential Diagnoses

Normal Structures

Reactive Lymph Node Hyperplasia

Sarcoid

Histoplasmosis

Other Malignancy

Diagnostic Checklist

Perform a baseline PET/CT in all patients with newly diagnosed NHL

TERMINOLOGY

Abbreviations and Synonyms

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL)

Large B-cell lymphoma

Low grade follicular B-cell lymphoma (FL)

Small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL)

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)

Marginal zone lymphoma (MZL)

Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT)

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL)

Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease (PTLD)

Hodgkin disease (HD)

Definitions

NHL: Malignancy of B or T lymphocytes

Low grade lymphoma

Slow growing, indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Low grade diffuse B-cell lymphoma

SLL: Termed CLL when 1° in blood or marrow

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (immunocytoma)

MZL: MALT; nodal marginal zone; splenic marginal zone

FL

Small-cleaved cell type: < 20-25% large cells

Mixed small-cleaved and large cell type: Survival inversely proportional to large cell percentage

Large cell type: Intermediate grade but more aggressive in nature

CTCL: Mycosis fungoides (MF), Sézary syndrome (leukemic variant)

CTCL: Rarely transforms into more aggressive large cell lymphoma

Separate entity from aggressive peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTL)

Also separate from adult T-cell lymphoma/leukemia (ATLL)

Extranodal lymphomas

Refer to lymphomas located in Waldeyer throat ring, thymus, and spleen

IMAGING FINDINGS

General Features

Best diagnostic clue

Pre-therapy evaluation

High grade NHL: Multiple enlarged lymph nodes or nodal groups with intense FDG activity ± splenic/other organ involvement

Low grade NHL: Enlarged LN, extranodal mass with low to intense FDG uptake

Marked FDG uptake may represent high grade transformation

“Misty mesentery” also a common finding in NHL

Occasionally normal-sized FDG-avid nodes

PET/CT Post-therapy evaluation

Absence of metabolic activity on FDG PET following treatment (high predictive value for disease free survival)

Persistent metabolic activity on FDG PET following treatment (moderate predictive value for recurrence)

Location

Superior mediastinal and paraaortic nodes common

NHL known for less predictable spread than HD

Head and neck region

Second most common site of NHL

Primary head and neck lymphoma accounts for 10-20% of all cases of NHL

Prone to be asymptomatic and unsuspected clinically

Usually presents on PET/CT as asymmetrical intense FDG activity in a lymphoid structure

Common locations: Palatine, lingual, sublingual tonsils, and adenoids

Pulmonary

Pulmonary involvement uncommon

Involvement without nodal disease seen more commonly in recurrent disease than at presentation

Also seen more commonly in PTLD

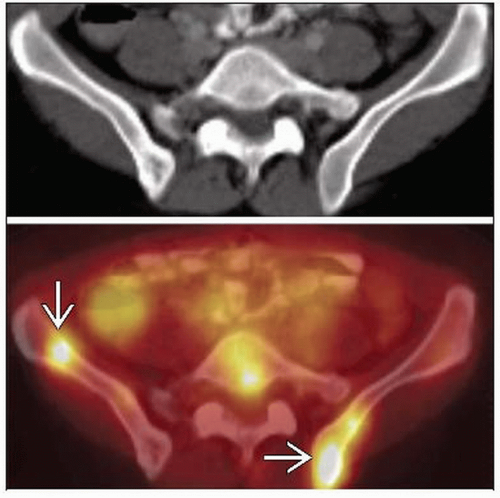

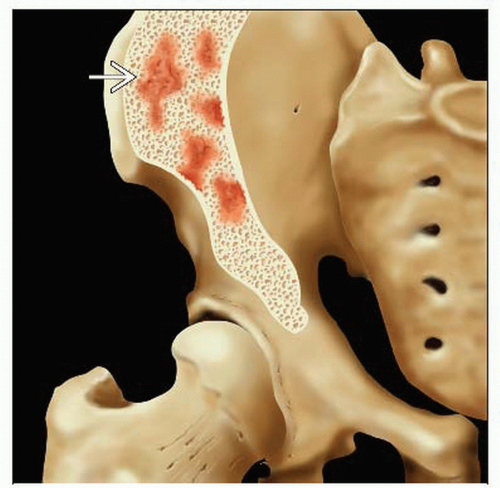

Bone marrow

PET/CT can help direct bone marrow biopsy to most metabolically active areas

Frequently have abnormal focal FDG activity without a correlative CT abnormality

Involvement found in 50-80% of low grade NHL and 25-40% of high grade NHL

Tends to signify advanced stage disease

Spleen

Involved in 20% of patients with NHL

Defined as nodal in HD, extranodal in NHL

Organ size is poor predictor; spleen can be large but not involved or normal with infiltration

PET/CT significantly more accurate than CT alone for detecting splenic involvement

May appear as multiple lesions or diffuse involvement on FDG PET

Other extranodal lymphoma

CNS, peripheral nervous system, lung and pleura, bone, skin, breast, testis, and GU tract

GI lymphoma represents approximately 10-15% of all NHL

Size

Most patients being evaluated for new onset lymphoma will have enlarged nodes

PET/CT will often detect additional normal-sized but malignant nodes

Lymph node size is a poor predictor of tumor involvement

Imaging Recommendations

Best imaging tool

PET/CT

Preferred modality for staging NHL

Sensitivity/specificity for evaluating malignant nodes: PET/CT 91%, 90% vs. CT 88%, 86%

Sensitivity/specificity for extranodal involvement: PET/CT 88%, 100% vs. CT 50%, 90%

Current and potential clinical applications of FDG PET/CT

Initial diagnosis: Evaluate adenopathy ± systemic symptoms without current pathologic diagnosis of NHL

Determine staging

Guide biopsy

Assess conversion to higher grade

Evaluate early response to chemotherapy

Determine restaging

Monitor post-treatment progress

Conventional imaging staging technique

CECT of neck, chest, abdomen, pelvis; occasionally MR

Uni- or bilateral bone marrow biopsy

Protocol advice

Consider PET/CT with contrast-enhanced CT for staging

Stage with PET/CT before any therapy is administered

One dose of chemotherapy may ↓ FDG uptake

Consider low dose CT for restaging/surveillance after a negative PET/CT following therapy

CT Findings

NECT

Enlarged lymph nodes

Can be large conglomerate masses with lobulated margins

Calcification rarely seen prior to treatment; frequently seen after therapy in larger confluent nodal masses

Size is not an independent predictive factor

CECT

Slight to moderate uniform enhancement following IV contrast

Marked enhancement unusual (low attenuation in 20% of cases)

Masses from lymphoma more likely to encase and displace the mediastinal structures

Unusual to constrict or invade them

Lung/Mediastinum

Intrathoracic involvement in 50% of newly diagnosed cases (vs. 85% in HD)

20% present with mediastinal adenopathy

Single or multiple discrete pulmonary nodules less well-defined and less dense than carcinoma

May cavitate (10-20%)

Consolidation with air bronchograms (solitary or multiple, includes pseudolymphoma)

Diffuse reticulonodular opacities (lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia)

Post-obstructive atelectasis due to nodal compression

Pleura

Pleural effusions seen in 10% of patients at presentation, due to lymphatic or venous obstruction

Effusion, may resolve with irradiation of mediastinal lymph nodes

Pleural masses rare

Pericardial

Pericardial effusion mostly coexists with adenopathy adjacent to pericardial margins

Associated with high grade peripheral T lymphoma, large B-cell lymphoma, and PTLD

Chest wall

Invasion with rib destruction uncommon

Nuclear Medicine Findings

Initial diagnosis

PET/CT used to evaluate enlarged nodes in patients without a history of lymphoma

Covered indication by CMS, but rarely used for initial diagnosis

Some NHL may not be FDG avid

MALT generally less FDG avid, but as a group MALTs have complex histology and may demonstrate uptake

PET for differentiation of indolent vs. aggressive lymphoma

Controversial topic

SUV ≥ 10 confers higher likelihood for aggressive disease (considerable overlap exists)

Staging

PET/CT more sensitive than CT for staging NHL

Consider baseline PET/CT for all patients with newly diagnosed NHL

Consider directed bone marrow biopsy to most metabolically active osseous structures detected on PET

Splenic involvement much more accurately assessed with PET/CT than with CT alone

Liver involvement may present as diffuse disease with patchy infiltrates originating in portal areas

Other patterns include miliary with multiple small lesions or, rarely, large focal lesions

False negative bone marrow biopsy may result due to patchy nondisseminated marrow involvement

Bone marrow biopsy (BMB) alone can detect minimal bone marrow disease, which may escape detection by PET

PET/CT shown to modify radiotherapy planning in 44% of patents with head/neck lymphoma

CLL/SLL: PET of limited use in staging 2° ↓ FDG uptake (sensitivity 58%)

SUV > 3.5 suggests Richter transformation of CLL/SLL → diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (sensitivity 91%, specificity 80%, PPV 53%, NPV 97%)

MZL: FDG PET staging sensitivity 71% (lower for extranodal)

MALT lymphoma: Typically no or low FDG uptake; SUV > 3.5 suggests plasmacytic differentiation

CTCL: FDG PET useful in staging, especially in suspected single cutaneous site

CTCL: Intense nodal sites suspicious for large cell transformation

FL: FDG PET useful in staging all grades (sensitivity 94%, specificity 100%)

Wide overlap between FDG uptake by lower (SUV 2.3-13) and higher grade (SUV 3.2-43) FL

Emergence of sites of ↑ FDG uptake (SUV > 10): Transformation to higher grade (specificity 81%)

Upstaging of extranodal disease observed mostly in stage I and II disease

Response to therapy

FDG PET demonstrates poor sensitivity for predicting likelihood of response/progression in patients with indolent lymphoma

PET excellent for predicting prognosis in aggressive NHL after therapy

Usefulness of follow-up scan hinges on existence of pre-therapy scan indicating FDG-avid disease

Early identification of therapy response allows modification of ineffective treatment

Nonresponders may avoid unnecessary side effects

Tumor FDG uptake decreases dramatically as early as first week post-treatment in aggressive NHL

Strong predictive value for 18 month outcome when imaged early in chemotherapy cycle, after only one cycle

FDG PET in early response assessment (after 1-4 cycles): Sensitivity 79%, specificity 92%, PPV 90%, NPV 81%, accuracy 85%

FDG PET in post-Rx assessment (mixed population HD, NHL): Sensitivity 79%, specificity 94%, PPV 82%, NPV 93%, accuracy 91%

FDG PET in post-Rx assessment NHL: Sensitivity 67%, specificity 100%, PPV 100%, NPV 83%, accuracy 88%

FDG PET in post reinduction chemo (before stem cell transplant): Sensitivity 84%, specificity 83%, PPV 84%, NPV 83%, accuracy 84%

1999 European Organization for Research

Post-therapy SUV that increases 25% over baseline indicates progressive disease

SUV decrease of 15-25% after cycle 1 of chemotherapy and 25% after more than 1 cycle indicates partial metabolic response

Ga-67-citrate less sensitive and specific than FDG PET for aggressive lymphomas

Chemotherapy can cause marrow hyperplasia and also generalized FDG uptake

G-CSF and recombinant erythropoietin can result in diffusely increased FDG uptake bone marrow and spleen, limiting sensitivity

Uptake due to growth factors usually returns to baseline by one month post-therapy

Restaging

Rationale for FDG PET imaging post-therapy

Allow for treatment of residual/progressive disease before it spreads further

PET can be positive months before histological confirmation of an asymptomatic relapse

Especially for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients

Benign FDG uptake patterns directly/indirectly associated with chemotherapy

Low level, patchy uptake in residual fibrotic mass and scars

Decreases over months but may persist

Diffuse FDG uptake in all adipose tissue (brown + yellow fat), adrenal/periadrenal regions

Concurrent chemo + protease inhibitors (lymphoma + HIV)

Skeletal muscle uptake

Pattern similar to carbohydrate-insulin effect

Granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) or other marrow stimulant drugs

Intense red bone marrow + splenic uptake/enlargement

May persist 2-3 months

Following cessation of chemotherapy

Increased thymic uptake (thymic rebound); diffuse FDG activity in thymus usually 4-8 months following chemotherapy

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Normal Structures

Thymus, salivary glands, muscle, tonsils

Look for symmetry

Can be asymmetrical if contralateral normal structure paralyzed (vocal cord) or surgically removed (muscle, glands)

Correlate with anatomical findings for confirmation of structure

Reactive Lymph Node Hyperplasia

Typically ↑ FDG uptake

Numerous sites, often symmetrical

LN mildly to moderately enlarged

May resolve over weeks to months

When equivocal, short term follow-up exam is usually helpful

Granulomatous Disease

FDG uptake moderate to marked

Stable over time

Often symmetrical hilar/mediastinal LN

Sarcoid

Lung nodules: Sarcoid “galaxy” sign; multitude of tiny clustered lung nodules along bronchovascular bundle

Garland triad (1-2-3 sign): Symmetrically enlarged bilateral hilar & right paratracheal LN

Enlarged anterior mediastinal LN favors lymphoma

Viral Infections; Infectious Mononucleosis

Minimally enlarged LN

Sub-cm lung nodules that usually resolve completely

Histoplasmosis

Sub-cm lung nodules that often calcify (granuloma)

Calcified normal-sized mildly FDG-avid mediastinal & hilar LN, calcified splenic & hepatic granulomas

Tuberculosis (TB)

Enlarged LN & ipsilateral consolidation in primary TB

Lung nodules may calcify, apical scarring, positive PPD

Cavitary lung lesion in the posterior segment right upper lobe or superior segment of the lower lobes

Cat-Scratch Fever

Enlarged, painful LN

Symptoms resolve over weeks

Whipple Disease

Enlarged abdominal LN with low attenuation center

HIV, AIDS

Higher Grade Lymphomas on Therapy

May show ↓ FDG uptake, mimicking low grade lymphoma

Other Malignancy

FDG PET may identify best candidate site for biopsy

Thoracic, Extrathoracic Malignancy

Enlarged FDG-avid LN accompanied by multiple FDG-avid lung nodules that increase in size and number over time

Small Cell Lung Carcinoma

Markedly enlarged, prominently FDG-avid hilar and mediastinal LN

PATHOLOGY

General Features

General path comments

Most common subtype in adults is diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Most aggressive subtype with 60% of patients having disseminated disease at diagnosis

More aggressive types

Diffuse large B-cell

Mantle cell

Peripheral T-cell

Fast-growing types

Burkitt lymphoma

Lymphoblastic

Slow-growing types

Marginal zone

Small cell (= CLL when principally in lymph nodes)

Lymphoplasmacytic

Follicular

Extranodal marginal zone lymphomas

GI tract, lung, salivary gland, conjunctiva, and thyroid

Diagnosed as separate entity termed MALT

Etiology

Unknown in most patients

MALT lymphoma (stomach) associated with H. pylori infection

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma: 1/3 associated with hepatitis C infection

Hashimoto thyroiditis associated with primary thyroid lymphoma

Epidemiology

NHL incidence ↑ 75% in the past 20 years, with ↑ mortality

Primary NHL of thyroid unusual, only 3.4% of primary thyroid malignancies

Malignant lymphomas as a group compose 5th most frequently occurring type of cancer in the USA

Most common NHL subtypes

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, 31%

Follicular lymphoma, 22%

Small lymphocytic lymphoma, 16%

Mantle cell lymphoma, 6%

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, 2%

Anaplastic large T-cell/null cell lymphoma, 2%

Burkitt-like lymphoma, 2%

Marginal zone nodal-type lymphoma, 1%

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma, 1%

Burkitt lymphoma, < 1%

Microscopic Features

T- or B-cell clonality: No Reed-Sternberg cells

Fine-needle aspiration is diagnostic in NHL

FL: Aggressiveness proportionate to percentage of large cells

Staging, Grading, or Classification Criteria

Histologic grading more important than staging of anatomic sites in NHL

Clinical staging

Includes history & physical examination

Imaging of the chest, abdomen, & pelvis

Blood count, chemistry, and bone marrow biopsy

Pathologic staging

Staging laparotomy & pathologic staging no longer routinely performed

REAL/WHO classification

Revised European-American Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms (REAL), adopted by World Health Organization (WHO)

Distinct disease entities defined by combination of morphology, immunophenotype & genetic features, and distinct clinical features

Relative importance of features varies by disease; no “gold standard”

Includes all lymphoid neoplasms: HD, NHL, lymphoid leukemias, & plasma cell neoplasms

Lymphomas & lymphoid leukemias included because solid + circulating phases are present in many lymphoid neoplasms

REAL/WHO classification of B-cell neoplasms

Precursor B-cell neoplasm: Precursor B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (precursor B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia)

Mature (peripheral) B-cell neoplasms

B-cell CLL/SLL; B-cell prolymphocytic leukemia

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma; splenic marginal zone B-cell lymphoma

Hairy cell leukemia; plasma cell myeloma/plasmacytoma

Marginal zone B-cell/MALT lymphoma

Nodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma; follicular lymphoma; mantle cell lymphoma

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; Burkitt lymphoma/Burkitt cell leukemia

REAL/WHO classification of T-cell and natural killer (NK)-cell neoplasms

Account for 10-15% of NHL

Precursor T-cell neoplasm: Precursor T-lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia (precursor T-cell ALL)

Mature (peripheral) T-/NK-cell neoplasms

T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia; T-cell granular lymphocytic leukemia; aggressive NK-cell leukemia

Adult T-cell lymphoma/leukemia (HTLV1+); extranodal NK-/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type

Enteropathy-type T-cell lymphoma; hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma; subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma

Mycosis fungoides/Sézary syndrome; anaplastic large cell lymphoma, T/null cell, primary cutaneous type

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise characterized; angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma, T/null cell, primary systemic type

Ann Arbor classification

Anatomic extent of disease in HD & NHL

Stage I

Single LN region (I)

Or localized involvement of a single extralymphatic site in the absence of LN involvement (IE) (rare in HD)

Stage II

≥ 2 LN regions, same side of diaphragm (II); or single extralymphatic site with regional LN

± Other LN stations, same side of diaphragm (IIE)

Stage III

LN regions, both sides of diaphragm (III)

May have extralymphatic extension with adjacent LNs (IIIE) or + spleen (IIIS) or both (IIIE, S)

Stage IV

Diffuse or disseminated disease in ≥ 1 extralymphatic organ

± LN; or isolated extralymphatic organ with or without regional LN

Any liver, bone marrow, lung nodules

Presence or absence of systemic symptoms

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree