Overview

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) is a heterogeneous group of diseases that accounts for 90% of lymphoma diagnoses, with the other 10% being Hodgkin lymphoma (HL). NHL arises during lymphocyte differentiation in either the humoral or cell-mediated immunity lineages of the immune system. Advances in molecular genetics and immunohistochemistry have increased the ability to differentiate distinct types of lymphoma, although not all of them are well understood. The 2016 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of NHL contains numerous subtypes of both mature B-cell lymphomas ( Table 24.1 ) and mature T-cell and natural killer (NK) cell neoplasms ( Table 24.2 ).

| MATURE B-CELL NEOPLASMS | |

|

|

a Plasma cell neoplasms, Hodgkin lymphomas, posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders, and tumors of histiocytic and antigen-presenting cells are not included in this panel.

| MATURE T-CELL AND NATURAL KILLER (NK)-CELL NEOPLASMS | |

|

|

a Plasma cell neoplasms, Hodgkin lymphomas, posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders, and tumors of histiocytic and antigen-presenting cells are not included in this panel.

Etiology, Prevalence, and Epidemiology

NHL is a common malignancy, with 386,000 cases reported worldwide in 2012 and 199,700 deaths in that year, per GLOBOCAN statistics. The incidence of NHL increased by 3% to 4% annually during the 1970s and 1980s, with relative stabilization in the mid-1990s. An estimated 72,240 new lymphoma diagnoses (4.3% of new cancer cases) will be seen in 2017 in the United States. The 5-year survival rate for NHL is 71% overall, and the 2014 prevalence of NHL in the United States was approximately 661,996 individuals.

Geographic differences are seen in the incidence of NHL. Incidence is highest in North America, Western Europe, and Australia/New Zealand. Annual incidence rates in the United States range from 19.9 to 21.4 per 100,000 people between 1994 and 2014. Within the European Union, national NHL incidence is quite variable, with Finland and Italy having the highest rates and former Eastern bloc countries having the lowest numbers of new cases.

Regional and socioeconomic factors also affect the distribution of lymphoma subtypes. Follicular lymphoma is most common in developed countries. The incidence of T-cell lymphoma and extranodal disease is greater in Asia. In Africa, Burkitt lymphoma is endemic, but overall incidence of NHL is low. Low-grade B-cell lymphomas are more common in high-income regions, whereas high-grade B-cell lymphoma is seen more commonly in low- and middle-income populations.

B-cell lymphomas are the most frequent type of lymphoma, constituting 85% to 90% of NHL. Multiple subtypes exist; diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common, followed by follicular lymphoma. Together they represent 65% of NHL. T/NK-cell lymphomas are much less common but equally varied. The principal subtypes of T-cell NHL are peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified; angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma; and anaplastic large cell lymphoma.

The most common risk factor for development of NHL is altered immune function, including autoimmune conditions, congenital immunodeficiency diseases, organ transplantation, and immunomodulatory infections, such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and human T-cell leukemia virus type 1. Other infections, notably Epstein-Barr virus and hepatitis C virus, are implicated in lymphomagenesis. Lymphoma is a disease of older people. Additional risk factors associated with development of B-cell lymphomas include medications, lifestyle factors, occupational exposures, and obesity. Some known risk factors for T-cell lymphomas are tobacco smoking, celiac disease, chronic skin conditions such as psoriasis and eczema, and textile or electrical work. Genetic factors also convey susceptibility.

Clinical Presentation

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma can affect any organ, and consequently symptoms at presentation may be varied and nonspecific. The most common finding is painless lymphadenopathy. B symptoms, such as night sweats, fever, pruritus, fatigue, and weight loss, may or may not be present. More aggressive lymphomas may be more symptomatic. In the thorax the most common sites of lymphoma involvement are the mediastinum, heart, lungs, pleura, and chest wall. Symptoms specific to thoracic lymphomas can include cough, chest pain, dyspnea, congestive heart failure, and superior vena cava syndrome.

Tissue sampling is required to make the diagnosis of NHL. Excisional biopsy is preferred, although core biopsy may be sufficient. Fine-needle aspiration and fluid cytology are not adequate for evaluation. Immunohistochemical studies and genetic analysis are recommended to accurately assign the lymphoma subtype and guide treatment planning.

Pathophysiology

B cell: All B lymphocytes originate in the bone marrow and travel to the spleen and lymph nodes, where they differentiate with the assistance of T cells into primary and secondary lymphoid follicles after encounter with an antigen. The secondary lymphoid follicle is characterized by germinal centers, which are the site of normal B-cell maturation. Within the germinal center, B cells proliferate rapidly and also undergo processes that require double-strand deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) breaks: class-switch recombination, by which the immunoglobulin heavy chain may be converted from immunoglobulin (Ig)M to IgG, IgA, or IgE; and somatic hypermutation, which orchestrates mutations of the light-chain variable immunoglobulin, IgV, in response to specific antigens. These processes carry the potential for DNA damage.

Many B-cell lymphomas have been associated with chromosome translocations that activate protooncogenes. As an example, t(14;18)(q32:q21) translocation is a common mutation in follicular lymphoma and causes overexpression of the antiapoptotic protein BCL2, which blocks programmed cell death in the germinal center. The “double-hit” lymphomas have combined defects in the transcription factor genes MYC and BCL2 or BCL6, and have particularly poor prognosis.

Lymphomas can also originate in activated B cells once they leave the germinal centers. The prognosis for germinal center lymphomas is better than that of activated B cells, with a 5-year survival of 76% and 16%, respectively.

T cell: Significantly less is understood of the pathophysiology of T-cell lymphomas, although they are thought to correlate with various stages of T-cell development. This is primarily because the diversity and rarity of the T-cell lymphoma subtypes hinder clinical and laboratory studies. Classification currently distinguishes between disease involving cells of innate immune system, such as NK cells and γδ T lymphocytes, and that affecting antigen-specific cells, including mature CD4 + and CD8 + αβ T cells and regulatory T cells. Advances in immunohistochemical analysis now allow differentiation between the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-positive and ALK-negative variants of anaplastic large cell lymphoma; one study showed that survival outcomes appear dependent on patient age and not the ALK status.

Imaging Evaluation

Radiography: Radiography is no longer used as a tool for assessment of lymphomas. However, chest radiography is commonly used as a preliminary imaging modality for nonspecific thoracic symptoms and may therefore reveal the first indication of a mediastinal mass, lung consolidation, or pleural disease.

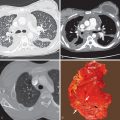

Computed tomography (CT): A CT examination is likely to be the initial study performed to assess abnormalities on chest radiography. This imaging modality is useful in identifying and characterizing the sites of disease in the thorax and developing a differential diagnosis. It may prompt further evaluation with additional multiplanar imaging modalities, depending on the findings and the level of clinical suspicion. A contrast-enhanced CT study is preferred if not contraindicated by renal insufficiency or allergy profile of the patient.

Positron emission tomography (PET) and PET-CT: PET imaging with 18 F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), particularly combined with CT, is now the imaging modality of choice for assessment of lymphoma. PET-CT has a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 100% in identifying nodal lymphoma as well as sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 100% for detecting extranodal disease. It has been suggested to be as sensitive as bone marrow biopsy in ascertaining bone marrow involvement. Different types of lymphoma can have different rates of FDG uptake: DLBCL and follicular and mantle cell lymphomas have avid uptake, whereas extranodal marginal zone lymphoma and T-cell lymphomas can have variable uptake ( Table 24.3 ).

| Histology | % FDG Avid |

|---|---|

| Burkitt lymphoma | 100 |

| Mantle cell lymphoma | 100 |

| Anaplastic large T-cell lymphoma | 100 |

| Lymphoblastic lymphoma | 100 |

| Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma | 100 |

| Natural killer/T-cell lymphoma | 100 |

| Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma | 97–100 |

| Follicular lymphoma | 91–100 |

| Nodal marginal zone lymphoma | 83–100 |

| Small lymphocytic lymphoma | 50–100 |

| MALT marginal zone lymphoma | 54–82 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree