30

Nonvariceal Upper GI Bleeding

Upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding refers to a bleeding site proximal tothe ligament ofTreitz and accounts for 80% of all gastrointestinal bleeding.1 From its onset, this entity must be recognized as potentially lethal, so diagnosis, resuscitation, and definitive treatment should be undertaken concomitantly. The mortality from acute non-variceal UGI bleeding is approximately 10% and has remained fairly constant over the past 50 years;2 it has been postulated that, despite advances in pharmacologic and endoscopic therapy, the mortality rate has remained the same because older, sicker patients have made up an increasing proportion of patients with gastrointestinal bleeding.3 On the other hand, in one article suggesting that there is some evidence of a decline in mortality over the past 10 years, endoscopic advances and the wider availability and increased effectiveness of treatment in intensive care units are credited with the improved survival.4

The epidemiology of UGI bleeding is not static. The number of hospitalizations for gastric ulcers increased by 20% and the frequency of bleeding gastric ulcers increased by 100% between 1980 and 1985; during the same period, however, hospital admissions for nonbleeding duodenal ulcers decreased dramatically.5 The increase in bleeding gastric ulcers has been attributed to the frequent use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and the lower incidence of duodenal ulcers has been attributed to the availability of histamine 2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs).6

UGI bleeding from a wide variety of sources stops spontaneously in approximately 80% of patients. Recurrent bleeding, however, occurs in as many as 25% of cases. In patients who have continued bleeding or rebleeding, mortality rates may be as high as 30 to 40%.7 Patients must receive prompt, effective treatment to preclude the onset of hemorrhagic shock and coagulopathy. Even when bleeding rapidly ceases spontaneously, identifying the source of the hemorrhage will facilitate rapid treatment if rebleeding occurs.

Clinical Approach to UGI Bleeding

Clinical Approach to UGI Bleeding

History and physical examination

A careful history and physical examination often will direct the physician to the cause of the bleeding and yield information regarding coexisting diseases and medications that may impact diagnosis and treatment. A history of pain preceding presentation or a history of peptic ulcer disease suggests peptic ulcer disease. The use of aspirin or other NSAIDs should raise the suspicion of peptic ulcer. A history of retching or vomiting before bleeding is classic for a Mallory-Weiss tear. Alcohol use or a history of blood transfusions increases the likelihood of liver disease with congestive gastropathy or varices. A previous history of pancreatitis should lead the physician to consider hemorrhage resulting from a pseudoaneurysm or pancreatic pseudocyst. Renal disease often is associated with GI bleeding.8 Approximately 50% of patients with acute renal failure have GI bleeding, often from peptic ulcer disease. Aortoduodenal fistula must be the primary consideration in patients with an aortic graft for aneurysm or occlusive disease, but it may occur with abdominal aortic aneurysms without previous surgery. A history of epistaxis, especially with skin telangiectasias, should raise the possibility of Osler-Weber-Rendu disease.

Physical evaluation should include evaluating for stigmata of cirrhosis, abdominal tenderness, and a rectal examination. Inspection of nasogastric and rectal contents may provide information regarding the prediction of mortality; with bleeding from peptic ulcers, mortality rates of 30% when there was a red nasogastric aspirate and red stool and 9% when the nasogastric aspirate and stool were black have been reported.9 Hematemesis generally indicates a more severe bleeding episode than melena.

Orthostatic hypotension (an increase in pulse rate by more than 20 beats per minute, a decrease in systolic blood pressure by more than 20 mm, and a decrease in diastolic blood pressure by more than 10 mm) may be the only physical finding and this usually occurs when there is a loss of 20% of intravascular volume or 1500 mL. Frank shock with supine hypotension and tachycardia indicates a volume loss approaching 40% or 2500 mL. Hypotension may result in transient hemostasis, and bleeding may recur when the blood pressure is restored to normal levels.

Resuscitation and management

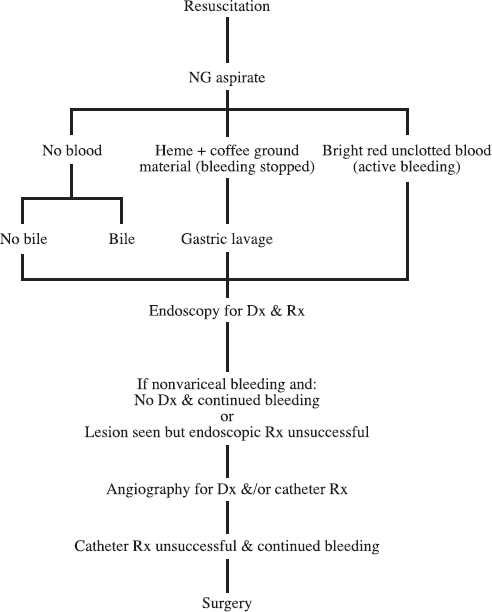

An algorithm for the management of UGI bleeding is shown in Figure 30-1.

FIGURE 30-1. Algorithm for management of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Nasogastric tube and gastric lavage

A nasogastric tube should be passed. Black coffee-ground material (due to gastric acid acting on hemoglobin to form acid hematin) that tests positive for blood is indicative of recent hemorrhage, and bright red unclotted blood suggests continued rapid bleeding. If the nasogastric aspirate does not show evidence of blood, it is important to note the presence or absence of bile; if bile is present, it is likely that the bleeding is from the lower GI tract or that a UGI source has stopped. If neither blood nor bile is present, the bleeding may still be from a duodenal ulcer with no reflux of duodenal contents into the stomach (one large survey showed that 12% of patients with no blood on nasogastric aspirate demonstrated active UGI bleeding on endoscopy).10 This same study showed a higher correlation between nasogastric return and endoscopy with gastric lavage and more prolonged nasogastric monitoring. Although melena (black tarlike stool) typically is seen with UGI or small bowel bleeding, it occasionally is seen with colonic bleeding. Frankly bloody bowel movements also can be due to bleeding from the stomach or duodenum and in these latter cases indicates rapid loss of more than 500 mL of blood.10 The airway should be protected in patients with a reduced level of consciousness or repeated episodes of vomiting.

Gastric lavage has been used since the late 1950s, when Wangensteen and colleagues introduced the principle of gastric hypothermia for control of UGI bleeding.11 Subsequent studies showed that lavage with saline at room temperature works as well as with ice solutions; indeed, cold-fluid lavage may impair coagulation, which occurs optimally at room temperature. Gastric lavage with a large-bore tube, regardless of the temperature and type of solution (saline, water, epinephrine), is a mainstay of treatment of UGI bleeding in most centers. Decreased gastric distension results in decreased gastrin release (and therefore decreased acid secretion). Although hemoglobin in the stomach helps to buffer acid, the fibrinolytic activity of retained blood outweighs the acid neutralizing action of blood.

Venous access lines

Large-bore (at least 16 gauge) peripheral or central venous access lines and (often) a urinary catheter should be placed. A Swan-Ganz catheter should be placed in patients who have underlying cardiac or renal disease or in patients in shock. Blood should be analyzed for type and cross-match for packed red blood cells. Blood should be drawn for hemoglobin, hematocrit, platelet count, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, calcium, and glucose. The hematocrit and hemoglobin do not change for the first few hours after hemorrhage because proportional amounts of plasma and red blood cells are lost; only as extracellular fluid enters the vascular space do these values fall, and this equilibration process may take from 24 to 72 hours. An elevated BUN with normal creatinine suggests a UGI source of bleeding. Oxygen should be administered because oxygen-carrying capacity is lost due to the loss of red blood cells (RBCs). The patient must receive appropriate blood and fluid replacement to maintain adequate intravascular volume and red cell mass, and coagulation defects must be corrected (usually with vitamin K or fresh frozen plasma). A hematocrit of 30% is a reasonable goal for most patients and provides a buffer should bleeding recur.

Histamine 2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs)

H2RAs reduce gastric acid secretion and are useful for ulcer healing, but they have not been shown to stop active bleeding or to definitely prevent rebleeding.12 H2RAs are extremely effective in preventing the formation of, and bleeding from, stress ulcers;13,14 their use in intensive care unit (ICU) patients accounts for the marked reduction in stress ulcers seen in ICU patients in recent years.

Endoscopy

Emergency endoscopy should be the first diagnostic test in patients with continued bleeding or if esophageal varices are suspected to be the source of bleeding. It should be noted that 20 to 30% of bleeding patients with varices will be bleeding from a source other than varices.15,16 Endoscopy should be performed as soon as all melenic material and clots have been evacuated by lavage. Endoscopy should be performed when bleeding persists after lavage, because endoscopy usually will be successful even in the presence of persistent bleeding. It is likely that hemorrhage from lesions bleeding so rapidly as to preclude endoscopic diagnosis most likely will not be stopped by further lavage.

The accuracy of endoscopy in identifying the cause of UGI bleeding ranges from 74 to 96%.17 It is important that endoscopy be performed as close to the bleeding episode as possible, because the longer the delay between cessation of bleeding and endoscopy, the less revealing will endoscopy be. In one study, the diagnostic accuracy decreased from 90% when endoscopy was performed within 48 hr of a bleeding episode to 33% when endoscopy was performed more than 48 hr from the cessation of the bleeding episode.18 The complication rate for emergency endoscopy has been reported to range from 0.1 to 8%, which contrasts with a complication rate of only 0.01% when elective endoscopy is used.19 All patients who do not undergo endoscopy emergently should have elective endoscopy within 24 hr of the initial bleed. This timing is important because (a) endoscopic signs (especially seeing pulsatile arterial blood) can be used to predict the risk for continued or recurrent hemorrhage with peptic ulcer,20 (b) multiple lesions are present in about 25% of cases and early endoscopy can identify the lesion actually responsible for the bleeding, (c) superficial lesions can heal in a short time, and (d) identification of the lesion responsible for bleeding makes it possible to direct therapy appropriately.

Causes of UGI Bleeding

Causes of UGI Bleeding

Endoscopic surveys10,21 show that acid peptic diseases account for up to 75% of cases of UGI bleeding, with equal numbers caused by gastritis, gastric ulcer, and duodenal ulcer; varices, esophagitis, duodenitis, and Mallory-Weiss tears account for most of the remaining cases. The following is a brief description of some of the major causes of nonvariceal UGI bleeding.

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD)

Whereas the number of hospitalizations, operations, and deaths from PUD have decreased in recent years, hospitalizations for bleeding ulcers have not decreased.22 PUD is particularly a problem of the elderly: the incidence of PUD increases with age. Of patients hospitalized for PUD complications, 70% are 60 years of age or older, approximately 80% of ulcer deaths occur in patients over 65 years, and the average mortality from complicated PUD in the elderly is 30%.22 Overall mortality from bleeding PUD is approximately 6%. Clinical risk factors that are correlated with an adverse outcome from bleeding PUD are hematemesis, red nasogastric aspirate that does not clear, clinical shock, age greater than 60 years, and associated illnesses. Endoscopic features associated with a poor outcome are location (high gastric ulcer, posterior duodenal ulcer), large size, and endoscopic stigmata of recent hemorrhage.20

Gastric ulcers penetrate the muscularis mucosa, which distinguishes them from superficial erosions. Although ulcers can occur anywhere in the stomach, the most frequent location is on the lesser curvature near the angularis.23 In 2 to 8% of cases, ulcers are multiple.24 Gastric ulcers are one fourth as common as duodenal ulcers.

There are many theories regarding the pathogenesis of gastric ulcers.25 Of patients who take NSAIDs, 25% develop gastric ulcers, and the risk of bleeding is twice that of gastric ulcers in patients who do not take NSAIDs.9 NSAID-induced duodenal ulcers occur slightly less frequently.26 The use of aspirin is associated with acute mucosal lesions and chronic ulcers.25,27 Smoking also has been associated with gastric ulcers.25

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative bacterium that was first isolated in 1982 and is believed to have a dominant causal role in chronic superficial gastritis.28 Because only a small percentage of patients with H. pylori develop ulcerations and because of the lack of strong evidence from animal models, it has been difficult to prove that H. pylori directly causes PUD; however, it is believed that infection with the organism may be a prerequisite for the occurrence of almost all duodenal ulcers in the absence of other specific precipitating factors.28 As mentioned, the prevalence of H. pylori is much higher than the incidence of peptic ulcers; however, almost all patients with duodenal ulcer and a somewhat smaller percentage of patients with gastric ulcer have H. pylori colonization of the stomach.29 Additional strong evidence that H. pylori causes peptic ulcers is the marked decrease in the recurrence rate of ulcers following eradication of the organism.28 It is not clear whether H. pylori and NSAIDs act synergistically to cause ulcers.

Acute hemorrhagic gastritis

This term describes superficial gastric mucosal lesions (which do not penetrate the muscularis mucosa) that result in bleeding. The erosions are found primarily in the body and fundus of the stomach. Hemorrhagic gastritis is associated with physiologic stress (related to trauma, surgery, burns, or severe medical problems), NSAIDs, alcohol abuse, and portal hypertension. Less frequent causes are gastric irradiation, ingestion of caustic substances, bile reflux, and long-distance running. In only 20% of cases is a predisposing cause absent.30 Duodenal erosions and gastric or duodenal ulcers may coexist with hemorrhagic gastritis.

Stress-related mucosal disease (SRMD)

This is a common cause of acute hemorrhagic gastritis and also a cause of duodenal mucosal bleeding. The formation of stress ulcers is multifactorial; factors that have been implicated are coagulopathy, reduced mucosal blood flow, inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis, bile reflux, reduced secretion of mucus and bicarbonate, and possibly increased gastric acidity.12,31,32 Following a major physiologic stress, nearly all patients show evidence of acute mucosal injury. Although SRMD occurs in most critically ill patients, it is particularly common with major trauma, severe burns, sepsis, and respiratory, renal, and hepatic failure. Endoscopic studies have shown that the incidence of gastroduodenal damage within 18 to 24 hours of admission to an ICU is between 52 and 100%.30 Before the use of H2RAs, clinically significant bleeding occurred in 5 to 20% of patients who had experienced a major physiologic stress, with a mortality rate approaching 50%.31,33

Mallory-Weiss tear

The Mallory-Weiss syndrome, a mucosal tear at the esophagogastric junction, was first described in 1929.34 Approximately two thirds of patients have an antecedent history of retching or vomiting, and 70% of patients are men.35 Alcohol ingestion traditionally is associated with Mallory-Weiss tears and is present in 40 to 75% of patients. Recent use of aspirin or NSAIDs (30%), blunt trauma, straining at stool, coughing, seizures, heavy lifting, primal scream therapy, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, increased intracranial pressure, pregnancy, and endoscopy are also associated with this lesion.36,37 80 to 90% of tears are on the gastric side of the esophagogastric junction, and the remaining 10 to 20% are in the esophagus.38 Other authors state that although tears may extend to the esophagus, they usually do not involve the esophagus alone.37 Hematemesis occurs in 85% of cases; 10% of patients present only with melena. Abdominal pain is rare. The diagnosis is made at endoscopy with visualization of a single linear mucosal tear in 80 to 90% of cases, with two or three tears seen in the remainder. Transfusions are required in only 40% of patients, and bleeding stops spontaneously in more than 90%ofcases. Managementisusually supportive. When intervention is necessary, electrocoagulation, compression with the gastric balloon of a Sengstaken-Blakemore or Minnesota tube, vasopressin (systemic or into the celiac or left gastric artery), and left gastric artery embolization all have been effective.37,39

Esophageal causes of UGI bleeding

Hemorrhage is an infrequent complication of peptic esophagitis and is more likely related to an inflamed hiatus hernia or Barrett’s esophagus. Hemorrhage in these cases may be the presenting symptom or may be superimposed on other symptoms of esophagitis. Hemorrhage usually is associated endoscopically with a discrete esophageal ulcer and less frequently by diffuse ulcerative esophagitis.40 Other esophageal diseases that may cause melena and hematemesis are fungal and viral infections and aortoesophageal fistula (as a result of foreign bodies, lung and esophageal cancer, aortic aneurysm, or perforation of an esophageal ulcer).41 Bleeding is usually fatal with aortoenteric fistulas.

Gastric tumors

Overt bleeding, more frequently melena than hematemesis, infrequently may be the presenting symptom of gastric cancer,42 or it may occur in patients with known tumors.43 Bleeding also can be the presenting symptom with gastric polyps, carcinoid, leiomyoma and leiomyosarcoma, lipoma, and liposarcoma. Bleeding also occurs with lymphoma, metastatic disease to the stomach, and pancreatic rests.

Dieulafoy’s disease

Dieulafoy’s disease is bleeding that occurs from a defect in an unusually large but histologically normal submucosal artery, through a minute mucosal erosion, usually in the proximal stomach; 75 to 95% of lesions occur within 6 cm of the gastroesophageal junction.44 Lesions also have been described in the gastric antrum, duodenum, jejunum, colon, and rectum.44 Whereas Dieulafoy’s disease is uncommon, it has been reported to account for 1.7 to 5.8% of cases of nonvariceal UGI bleeding.44,45 Although alcohol, aspirin, NSAIDs, and PUD have been reported to be associated with Dieulafoy’s,45 these associations remain controversial.37

It is not known why the enlarged submucosal artery is present or what causes the mucosal erosion or defect over the artery. The two main theories are that a normal artery becomes elongated with aging, and that a large submucosal artery is congenitally abnormally close to the mucosa. In either case, the tortuous artery may cause pressure on the mucosa, leading to mucosal ischemia and erosion, which are followed by arterial rupture.44 Dieulafoy’s disease can cause massive bleeding and can be difficult to see endoscopically because of the small mucosal defect. The Dieulafoy lesion is identified endoscopically in 82% of cases (49% were identified on initial endoscopy, 33% during a second examination, and 18% were seen only at surgery).46 The typical presentation is a middle-aged or elderly man (the male-to-female ratio is 2:1) with sudden massive hematemesis, melena, and hemodynamic instability. Angiography can identify extravasation when bleeding is active, but Dieulafoy’s lesions have no specific angiographic signs.47 A review of endoscopic treatment of Dieulafoy’s disease in 1991 showed that permanent hemostasis was achieved in 85% of cases and that 15% rebled, requiring a second therapeutic endoscopic procedure.46

Aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms

Chronic pancreatitis causes pseudoaneurysms by enzymes eroding arterial walls and by pseudocysts eroding into arteries (variceal bleeding resulting from splenic vein occlusion also may occur). These problems are unusual but life-threatening complications of chronic pancreatitis. Pseudoaneurysms of pancreatitis rupture and bleed more frequently than true splenic artery aneurysms. Hemorrhage from these pseudoaneurysms tends to be intermittent, repetitive, and sometimes massive. Pseudoaneurysms can bleed into the pancreatic parenchyma or the GI tract through the pancreatic duct; presentation usually is associated with bleeding into the lumen of the GI tract, but patients may present with pain resulting from pancreatitis or the pseudocyst. The splenic, gastroduodenal, and pancreaticoduodenal arteries most frequently are involved, but pseudoaneurysms can originate from any branch of the celiac or superior mesenteric arteries. Ten percent of patients with chronic pancreatitis will demonstrate pseudoaneurysms on arteriography.48 Of pseudocysts, 2 to 10% have been reported to hemorrhage with a mortality rate of 40 to 80%.49

Hemobilia

Hemobilia

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree