Fig. 1

Plain radiograph of a normal lumbar spine and of lumbar spondylosis. a Lateral view of a normal lumbar spine. b Anteroposterior view of a normal lumbar spine. c Lateral view of a patient with lumbar spondylosis. Marginal osteophyte (arrowhead) and narrowing of a facet joint (arrow) are present. d Anteroposterior view of a patient with lumbar spondylosis. Notice the marginal osteophytes (arrowhead) at multiple levels

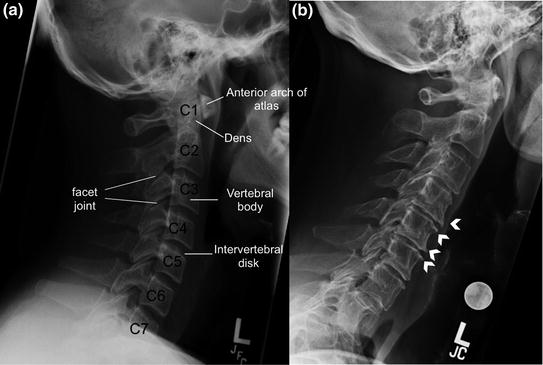

Fig. 2

Plain lateral radiographs of a normal cervical spine (a) and of a patient with cervical spondylosis (b). Marginal osteophytes are denoted by arrowheads

Grade 0 | None |

Grade 1 | Doubtful |

Grade 2 | Minimal |

Grade 3 | Moderate |

Grade 4 | Severe |

In patients with progressive neurologic symptoms, or in patients with persistent pain and severe radiographic spondylosis, MRI is the imaging test of choice. It provides a better resolution for structural changes, and is ideal for visualization of the spinal cord, the intervertebral disk, and the soft tissues.

CT is superior for detection of bony changes, especially small osteophytes or erosions arising from the lateral edge of the vertebral body and the facet joints (Fig. 3). However, because of the exposure to radiation, it is only used in patients with contraindications to MRI, and when establishing a firm diagnosis is needed to guide treatment.

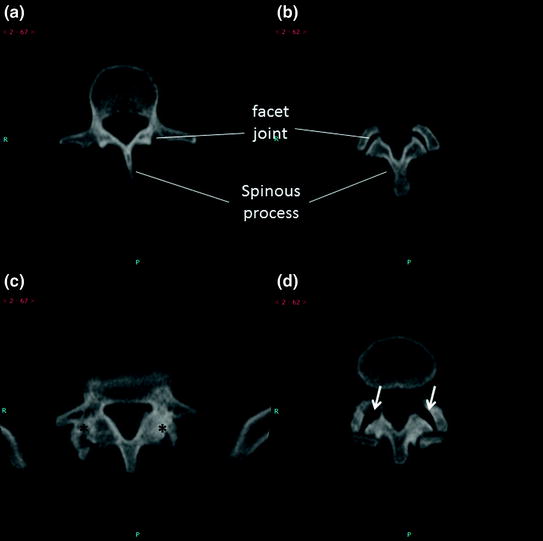

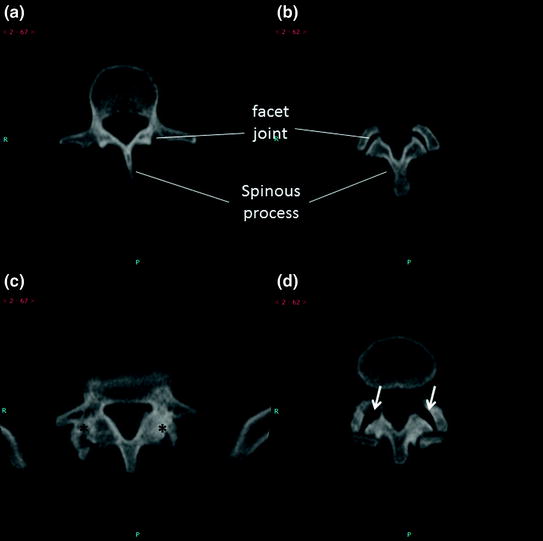

Fig. 3

Facet joint osteoarthritis on computed tomography. a, b Axial view of a normal lumbar spine. c, d Axial view of a lumbar spine with facet joint osteoarthritis. Hypertrophy (asterisks) and erosions (arrows) are common findings in facet joint osteoarthritis

As degenerative changes are common in older people and are not always symptomatic, the interpretation of MRI results (or CT with myelogram) should be cautious and correlated with the clinical findings for diagnosis and further management.

2.2 Degenerative Disk Disease

2.2.1 Definition and Occurrence

Degenerative disk disease is a group of conditions caused by wear and tear changes of the intervertebral disks. It is usually a part of the aging process; however, in rare conditions, accelerated degeneration occurs, causing juvenile degenerative disk disease.

The intervertebral disk is composed of the gelatinous nucleus pulposus in the center, surrounded by the annulus fibrosis, which is composed of layers of dense, fibrotic tissue. With aging, the disk undergoes three phases of degenerative changes [10]. In phase I, or the dysfunctional phase, microtrauma from repetitive use causes small tears and fissures in the annulus fibrosis, associated with pain. Meanwhile, the nucleus pulposus loses water content. MRI study often reveals disk bulging without herniation and tears in the annulus. In phase II, or the unstable phase, more tears occur and lead to disk disruption, resorption, and loss of the disk space. Local inflammation may follow if the herniated disk compresses the spinal nerve root. Cartilage degeneration and malalignment can develop in the facet joints. Clinically, patients often present with spine instability and symptoms related to nerve irritation. Phase III is the stabilization phase. With disk resorption and disk space narrowing, mechanical stress leads to fibrosis of the disk and degenerative changes at the vertebral endplates.

The prevalence of degenerative disk disease is difficult to estimate. In a MRI study in 239 asymptomatic individuals with a mean age of 39 years, degenerative cervical disk disease progressed in 81 % of the study subjects over 10 years [11]. In patients with cervical radiculopathy, disk protrusion was identified as the cause in 21.9 % of patients [12]. In a study of cervical MRI scans of patients undergoing throat surgery who had no neck pain, cervical disc protrusion or herniation was incidentally seen in 20 % of patients aged 45–54, and 57 % of those older than 64 [13]. Lumbar degenerative disk disease affects young to middle aged people as well, with a peak incidence at age 40 years. A recent study using MRI of the whole spine of 975 individuals found degenerative disk disease in 71 % of men and 77 % of women younger than age 50 years, and in more than 90 % of men and women older than age 50 years [14].

2.2.2 Clinical Manifestations

Degenerative disk disease may present a wide spectrum of symptoms, and MRI studies have shown that the degree of disk degeneration does not correlate with the symptoms [15, 16]. The majority of patients with degenerative changes on MRI remain asymptomatic for years [11].

Common symptoms include pain and nerve dysfunction such as radiculopathy. Radiculopathy is caused by the compression of a spinal nerve root from a laterally herniated disk. It is one of the most common causes of acute pain of the neck or the back. In cervical disk herniation, pain usually affects the arms, shoulders, the region between the shoulder blades, or the rib cage, and can mimic chest pain. Persistent compression will lead to numbness, tingling, and weakness of the arms or the hands, in the areas supplied by the compressed spinal nerve. In one series, 70 % of patients with cervical radiculopathy were found to have lesions at the disk between the sixth and seventh cervical vertebrae (C6–C7), and 20 % of patients had lesions at the C5–C6 intervertebral disk [17].

In lumbar disk herniation, pain is usually in the low back, travelling to the buttocks or down the leg to below the knee. Pain is usually worsened with bending forward, coughing, or sneezing. Numbness, tingling, and weakness of the leg may occur. The straight leg test is a physical exam test used to assess lumbar disk herniation, with specificity of 89 % and sensitivity of 52 % [18].

A large central disk herniation may cause compression of the spinal cord, with neurological symptoms compatible with myelopathy or cauda equina syndrome in the lower lumbar spine. Detailed clinical manifestation will be discussed in the section on spinal stenosis.

Disk pain is caused by irritation on the annulus fibrosis. It comprises neck pain or back pain, extending along the spine, without associated neurologic symptoms. A diagnosis of discogenic pain is based a fluoroscopic provocative test, and will be discussed in detail in the imaging section.

2.2.3 Treatment

No treatment is needed for asymptomatic patients. For patients with pain along the spine without nerve symptoms, conservative management is appropriate. Most patients have a benign course. In a study with 19 years of follow up, 75 % of patients had only one episode of pain or mild recurrent symptoms [7]. Pain management with NSAIDs, muscle relaxant during acute episodes, exercise, and cervical or lumbar traction, are commonly used.

In patients with progressive neurologic symptoms, MRI is indicated. If compression of the spinal nerves or nerve roots by a herniated disk is found to be the cause of symptoms, local injection of corticosteroids is often used, especially in cases of lumbar disk herniation. Without treatment, persistent compression may lead to permanent damage of the nerve, and lead to irreversible nerve symptoms. If compression of the spinal cord is present with clinical symptoms of myelopathy, definitive surgery is indicated.

2.2.4 Imaging

Plain radiographs of the spine have limited use in diagnosing degenerative disk disease, although some radiographic findings indicate degenerative disk disease. These findings include narrowing or loss of the disk height (Fig. 4), sclerotic changes of the vertebral endplates, and, in later stages, the presence of osteophytes and sclerosis of the facet joints. “Vacuum phenomenon” is considered a specific radiographic indicator of disk degeneration. With degeneration of the disk, gases transpired from the circulation accumulate in the space that the nucleus pulposus once occupied, causing the intervertebral disk space to appear radiolucent (Fig. 4). In general, in the absence of trauma, radiographs are not always needed.

Fig. 4

Severe degenerative disk disease and lumbar spondylosis on plain radiograph. Lateral view of a lumbar spine. Narrowing of intervertebral disk space (black arrow), complete loss of disk space (asterisk), and vacuum phenomenon (white arrow) are characteristic features of degenerative disk disease. Osteophytes originating from vertebral bodies (black arrowheads) and facet joint narrowing (white arrowheads) are present, signifying associated spondylosis

Provocative discography may be used to confirm that a degenerative disk is the source of neck pain or back pain in difficult cases [19]. Under fluoroscopy, a diseased disk is injected at a certain pressure to see if this procedure reproduces the patient’s pain. If the injection to an adjacent normal disk does not reproduce the pain, the test is confirmatory.

MRI is the standard imaging modality for detecting disk disease. It is indicated in patients who have progressive neurological symptoms despite conservative management, or in patients who plan to undergo surgery. On MRI, a degenerated disk has decreased intensity on T2 weighted images, due to loss of water content and glycosaminoglycans [20]. Bulging of the annulus (Fig. 5a), herniation of the disk contents (Fig. 5b), and loss of intervertebral disk height can be demonstrated on MRI. Early changes of disk degeneration, such as tears of the annulus fibrosis, can be seen as high intensity zone lesions [21, 22].

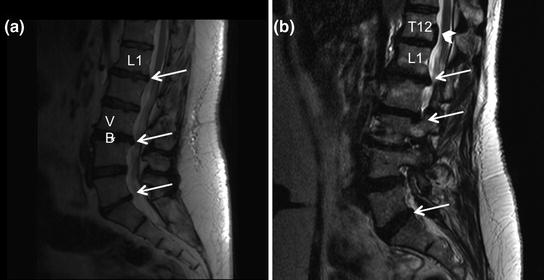

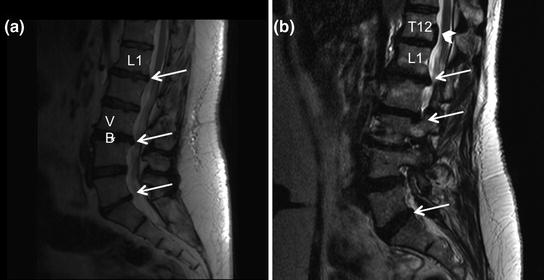

Fig. 5

Degenerative disk disease by magnetic resonance imaging. Sagittal view of a lumbar spine, T2 weighted images. a Disk bulging at multiple levels, most prominent at L1–L2, L3–L4 and L5–S1, and indenting the spinal canal (arrows). VB indicates vertebral body; Asterisk indicates intervertebral disk. b Disk herniation at the T12–L1 level, with migration of disk material posterior to the T12 vertebral body (arrowhead). Disk bulging (arrow) is present at L1–L2 and L2–L3 as well

CT scan can depict degeneration, bulging and herniation of the disk, but with much less detail than MRI. CT can also show sclerotic changes of the vertebral endplate and loss of the disk height, which are commonly seen in degenerative disk disease, but these findings most often can be readily seen on plain radiographs. Clinically, CT is used in patients with contraindications to MRI.

2.3 Spinal Stenosis

2.3.1 Definition and Occurrence

Spinal stenosis is a condition of narrowing of the central spinal canal, causing compression on the structures within the canal, mainly the spinal cord and spinal nerve roots, with associated nerve dysfunction. The spinal cord extends from the base of the brain and ends at the level of the first and second lumbar vertebrae (L1–L2). Spinal nerves branch off the spinal cord and course alongside it before exiting the spinal canal. Below the L1–L2 level, the spinal nerves form a bundle called the cauda equina. Anatomically, when compression happens above the L1–L2 level, both the spinal cord and the nerve roots can be affected, while below the L1–L2 level, compression of the nerve roots alone is seen. Both direct mechanical compression and secondary changes due to lack of blood supply contribute to damage of the spinal cord and nerve roots. When the spinal cord is affected, it is called myelopathy, and when the spinal nerve roots are involved, it is termed radiculopathy.

Spondylosis is the most common cause of spinal stenosis in people older than 60 [23]. Osteophytes of the facet joints, disk bulging, and calcification and overgrowth of the posterior longitudinal ligament and ligamentum flavum can slowly encroach the spinal canal, and eventually lead to compression of the spinal cord or nerve roots. Spondylolisthesis, a condition in which the one vertebra slips relative its neighboring vertebra, can be a cause of lumbar spinal stenosis, especially at the L4–L5 level.

Conditions other than degenerative changes can cause spinal stenosis, including tumors and post-operative scar tissue. Inflammatory conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis, may lead to overgrowth of the synovium at the facet joints, with compression of the spinal cord in severe cases. Some people are born with a narrow spinal canal and are susceptible to spinal stenosis with even minor changes in spine anatomy or mild degrees of degenerative disease. Spina bifida is another congenital cause of spinal stenosis.

Spinal stenosis usually has an insidious onset. It can be an incidental finding on radiologic study in asymptomatic individuals. It occurs in 20–30 % of people older than 60 years of age [24]. In a study of 187 individuals, the prevalence of lumbar spinal stenosis increased with age, affecting 2.1 % of people aged 40–49, 6.1 % of people aged 50–59, and 16.3 % of people older than 60 years [25].

2.3.2 Clinical Manifestations

In patients with cervical spinal stenosis, neck pain or pain in the area below the shoulder blades is frequently reported. When the narrowing and compression damage the cord, neurological symptoms develop. Clumsiness and weakness are common, and both the arms and legs may be affected. Many patients experience loss of sensation, often associated with numbness and tingling. When the spinal cord is compressed, a sensory plane can be detected, separating the body into areas with normal sensation above the plane and areas without normal sensation below the plane. If a nerve root is affected, the sensory change is often distributed in the skin area supplied by the compressed spinal nerve, or in other words, in a dermatomal pattern. Patients may also experience difficulty with urination or having bowel movements. On physical exam, patients are found to have an abnormal gait early in the course of disease, indicating weakness of the legs. Neck motion is often limited. Lhermitte’s sign is a characteristic finding, and can be induced by bending the neck. When this sign is present, patients experience a sensation of an electric shock in the neck, shooting down to the arms and along the spine.

Rarely, cervical spinal stenosis presents acutely. This can happen after minor injury or whiplash injury. These patients often have pre-existing degenerative changes, and a minor disturbance then leads to worsening and onset of nerve symptoms, with rapid progression of weakness, sensory changes, and bladder or bowel dysfunction.

The common clinical presentation of lumbar spinal stenosis was well characterized in a cohort of 68 patients [26]. Back pain, often travelling down the legs, numbness, and weakness of the legs are common. A prominent feature is neurogenic claudication, with worsening of symptoms on walking or standing, and relief when sitting or bending forward. On exam, patients are often found to have a wide-based gait. Weakness and sensory changes are distributed in one or more spinal nerve areas, indicating radiculopathy. Cauda equina syndrome is a rare complication of lumbar spinal stenosis, with weakness of both legs associated with urinary dysfunction. If spinal stenosis occurs higher in the spine than the L1–L2 level, damage of the spinal cord will cause myelopathy, with presentation similar to that of cervical spinal stenosis, but involving the legs.

2.3.3 Treatment

Conservative management is the mainstay treatment for spinal stenosis. In patients with cervical spinal stenosis, immobilization with a soft collar or a brace is often recommended. Activities such as action sports or intense neck movements should be avoided. Prevention of whiplash injury during motor vehicle accident is important. For patients with lumbar spinal stenosis, although evidence is lacking, exercise is recommended with a goal to strengthen muscles and to maintain correct posture. Pain control with acetaminophen and NSAIDs is commonly used, and can be escalated to opioids if needed. Epidural injection of corticosteroids is used in lumbar spinal stenosis, but with limited evidence supporting its effectiveness.

In some cases, compression can be relieved by surgery. However, the indications for surgery and its timing have not been well studied. Commonly, surgery is considered in patients with progressive nerve symptoms or moderate to severe symptoms with difficulty performing daily tasks [26]. In patients with spinal stenosis but without neurologic symptoms, surgery can be deferred with close monitoring [26, 27].

Acute nerve symptoms may be the first presentation in some patients, and is a medical emergency. Immediate MRI is indicated for diagnosis and assessment of severity. Neurosurgery or orthopedic evaluation for potential surgical intervention is essential. Treatment with high dose intravenous corticosteroids to decrease acute inflammatory changes in the spinal cord may improve outcomes [28].

2.3.4 Imaging

The diagnosis of spinal stenosis is based on imaging and a compatible clinical presentation. Plain radiographs have limited utility for this condition. It is used in cases of neck pain or back pain without neurologic symptoms to exclude other conditions. In patients with nerve symptoms, MRI is the study of choice, while CT with myelography is used in patients with contraindications to MRI. Direct compression of the spinal cord can be visualized on MRI, and it may or may not be associated with a signal change in the spinal cord. Findings may be present in one or multiple vertebral levels.

Measurement of the anteroposterior diameter of the spinal canal or the intraspinal canal area has been suggested as radiologic diagnostic criteria of spinal stenosis [24], and for assessment of myelopathy [29, 30], however it has not been routinely used in clinical practice. More importantly, radiologic spinal stenosis is an incidental finding in 6–7 % of asymptomatic individuals, and its prevalence increases to 20–30 % in people older than 60 years [24].

Abnormal MRI signal in the spinal cord can be a useful marker of myelopathy (Fig. 6). Hyperintense signal on T2-weighted imaging, hypointense signal on T1-weighted imaging, and hyperintense signal on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) have been evaluated for their correlation with clinical findings, and DWI has a better correlation [31, 32].

Fig. 6

Cervical spinal stenosis with spinal cord compression by magnetic resonance imaging. Sagittal view of a cervical spine, T2 weighted images. At the C4–C5 level, intervertebral disk bulge compresses the spinal cord, associated with hyperintense signal at the corresponding level (arrow), indicating structural damage of the spinal cord. Asterisks mark intervertebral disks

2.4 Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis

2.4.1 Definition and Occurrence

Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) is a non-inflammatory condition characterized by calcification and ossification of ligaments, with a predilection for the spine. It most commonly affects the anterior longitudinal spinal ligament, particularly in the thoracic spine. Large flowing osteophytes with an appearance of ‘candle wax dripping down the spine’ is the typical finding in this condition. Thickening, calcification, and ossification may also involve peripheral ligaments, especially at sites of the tendon insertions. Unlike spondylosis, in which the primary pathologic target is cartilage, the discovertebral joints and the facet joints are usually intact in DISH. Lack of sacroiliac joint involvement and inflammation distinguishes DISH from ankylosing spondylitis [33, 34]. The cause of DISH remains unclear.

DISH is rare in people younger than 40 years old. It generally affects people older than 50, with a prevalence of 15 % in women and 25 % in men. This prevalence increases to 26–28 % in those over 80 years [35].

2.4.2 Clinical Manifestation

DISH is largely asymptomatic. Patients may report pain in the spine and legs, morning stiffness, and limited spine flexibility. Pain in the upper back is common, and is often associated with limited chest expansion. The cervical spine and lumbar spine may also be involved. Although rare, in severe cases, large calcifications may impinge on the airway to cause difficulty or pain with swallowing, hoarseness, or high-pitched sounds from the throat with breathing. In the peripheral joints, calcification of the ligaments and entheses (sites where tendon attach to the bone) cause local pain, and can limit movement of the affected joints. Some patients have tenderness and nodules of the entheses.

2.4.3 Treatment

Pain control with acetaminophen and NSAIDs is the mainstay of treatment. Physical therapy and exercise may relieve some symptoms and improve function. Surgery is needed if compression is present and causing symptoms.

2.4.4 Imaging

The current accepted diagnostic criteria for DISH is based on plain radiography of the thoracic spine [36]. Large, flowing right-sided ossification over the thoracic spine is typical, extending over at least four vertebral bodies (Fig. 7). Preservation of intervertebral disk heights and absence of facet joint and sacroiliac joint involvement are also required for diagnosis.

Fig. 7

Plain radiograph of the thoracic spine in a patient with diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis. Anteroposterior view of a thoracic spine. Radiolucent areas (arrow) indicate space between ossified longitudinal ligament and the vertebral bodies. The changes are predominantly located on the right side of the thoracic spine

3 Inflammatory Arthritis

3.1 Ankylosing Spondylitis

3.1.1 Definition and Occurrence

Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS, from the Greek ankylos, fused; spondylos, vertebrae; –itis, inflammation) is the prototypic disease of the seronegative spondyloarthritis family, a group of inflammatory spinal arthritis that includes AS, psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis, spondyloarthritis associated with inflammatory bowel disease, and undifferentiated spondyloarthritis. In contrast to rheumatoid arthritis, patients with seronegative spondyloarthritis usually do not produce autoantibodies, such as rheumatoid factor or anti-cyclic citrullinated protein (anti-CCP) antibody, and therefore are termed “seronegative.” AS primarily involves the axial skeleton, including the spine and sacroiliac joints, with features of chronic inflammation and new bone formation. The sacroiliac joints are the connections between the lower end of the spine (sacrum) and the pelvis.

Genetic factors are important in the susceptibility to AS. Early study of AS in 1970s discovered an association with a gene called human leukocyte antigen B27 (HLA-B27) [37]. It is estimated that 85–90 % of patients with AS have HLA-B27, compared to under 10 % of the general population [38]. Among those who have HLA-B27, AS is more common among those with a close relative who also has AS than in those without any close relative with AS [39]. This indicates other genetic factors are involved in the pathogenesis of AS. Recent genome-wide association studies have advanced our understanding of the genetic basis of AS. More than 20 genes, e.g. ERAP1, IL-23R, KIF21B, etc., and a few intergenic regions, e.g. 2p15 on chromosome 2, are now identified to be associated with AS [40–42]. Substantial evidence suggests environmental factors trigger the onset of AS in people with certain genetic background, a theory well supported by the study of HLA-B27 transgenic rats. These rats develop arthritis and gut inflammation, resembling human HLA-B27 associated diseases. Interestingly, they are protected from the disease if raised in germ-free conditions [43].

Chronic inflammation of the entheses and new bone formation are two cardinal features of AS. Entheses are the sites where tendons or ligaments insert into bones. Immunohistologic staining of entheses from the sacroiliac joints [44] and the foot ligaments [45] of patients with AS showed inflammatory cell infiltration at these sites. In addition to enthesitis, inflammation occurs in bone (osteitis) and synovium (synovitis), and can cause pain and swelling.

New bone formation is a slow and insidious process, with new skeletal tissues formed in connection with, but extending outside the original bone [46]. Bony growths originating from the ligament insertions of the spine are called syndesmophytes, while those originating from the entheses in the extremities are called enthesophytes. Growth of syndesmophytes starts at the thoracolumbar junction, gradually involves other spinal areas, and may eventually lead to bridging of vertebral bodies and complete fusion (ankylosis) of the spine, causing significant loss of mobility. The same process happens at the sacroiliac joints, causing ankylosis. Several molecular pathways have been proposed to be involved in this process, including bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs), Wnt protein, hedgehog protein and fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) [46]. The relationship between chronic inflammation and new bone formation remains unclear.

The prevalence of AS ranges from 0.1 to 1 % of the population, depending on the ethnic groups studied. Caucasians and Native Americans have the highest prevalence, while AS is rare in Africans. Men are 3 times more likely to have AS than women, and often have more severe disease. AS tends to run in families, with an estimated heritability of more than 90 % [47]. It usually begins during adolescence or early adulthood, and is life-long.

3.1.2 Clinical Manifestations

Inflammatory back pain is the most common symptom in patients with AS. Patients often describe pain in their lower back or the buttock, worse after rest, especially during the second half of the night. They often report waking up in significant pain and stiffness in the morning. Exercise and NSAIDs improve the back pain. The symptoms usually fluctuate, and are often associated with fatigue.

With progression of the disease and the growth of syndesmophytes, ankylosis of the spine becomes a more prominent feature in the disease presentation. In advanced stages of AS, patients may develop a stooped posture, have decreased movement of their spine, and significant loss of function. Fusion of the cervical spine leads to a forward flexion of the head, and patients may have difficulty raising their head to look straight ahead. Involvement of the thoracic spine and the chest wall may make it difficult for patients to expand their chest and take deep breaths, affecting the function of the lungs. In severe cases, patients may develop roundback, which prohibits them from sleeping on their back. Lumbar spine involvement may make it difficult for patient to bend forward and reach the floor. Complete fusion of the spine makes patients more susceptible to trauma and spine fractures. The extent of spine fusion varies greatly among patients, and progression to complete fusion is not inevitable.

Complaints in the limbs are common, mainly due to enthesitis and arthritis. Inflammation of the entheses causes intermittent pain and swelling at various tendon insertion sites, for example, at the heel, where the Achilles tendon attaches, or at the bottom of the foot. Hips, shoulders and collarbone joints are frequently involved with pain, stiffness, and sometimes swelling, indicating ongoing inflammation. Over time, inflammation may causes damage, with erosion of the bone and loss of cartilage and the joint space. Joint movements may become limited, for example, with flexion contracture of the hips.

Paradoxically, despite the propensity to add extra abnormal bone to the spine, patients with AS often develop osteoporosis, a condition of decreased bone density, with increased risk of fracture. Organs other than musculoskeletal system are affected in AS. Common manifestations include uveitis (inflammation of eyes), aortitis (inflammation of the aorta, the largest artery in the body, originating from heart), and colitis (inflammation of the large bowel). Inflammation can also lead to secondary amyloidosis (a process of protein deposition in internal organs), usually associated with kidney dysfunction.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree