Fig. 9.1

Radiation therapy-related changes in a prostate needle biopsy are characterized by a diminution in the number of neoplastic glands, which are often poorly formed and haphazardly arranged within the prostatic stroma (left). Immunohistochemistry with triple stain that combines two basal cell markers (p63 and high molecular weight cytokeratin [clone 34betaE12] in brown) and alpha-methylacyl-CoA racemase (AMACR) (in pink/red). The glands with no brown and only red-pink are cancerous glands, while those with the both red-pink plus a brown rim are benign (right). Figure courtesy of Samson W. Fine, MD, of the MSKCC Department of Pathology, Surgical Pathology Diagnostic Services, Genitourinary Pathology. Used with permission

Salvage Radical Prostatectomy

Early recurrence of prostate cancer is likely to be organ confined and therefore amenable to salvage therapy. Although salvage RP has been used successfully to eradicate locally recurrent prostate cancer after definitive RT, complications are common [6, 9, 15–17]. Accordingly, the procedure should only be performed by experienced urologic surgeons. Patient selection should be limited to those in excellent health, with a life expectancy of at least 10 years, whose cancer (whether initial org recurrent) is clinically organ-confined and potentially curable. Patients should have no evidence of metastatic disease, no evidence of lymph node involvement before RT, and no evidence of severe radiation cystitis or proctitis. Salvage RP is technically feasible using current surgical techniques, with satisfactory immediate intraoperative and postoperative outcomes [15]. The majority of patients can be treated via a retropubic approach; rarely is a combined abdominoperineal approach required. The rate of major complications has decreased from 33 to 13 % for patients treated before and after 1993 (p = 0.02) and rectal injury has been encountered in only 1 of 60 patients (2 %) since 1993.

Salvage RP can be safely performed after failed external beam RT, brachytherapy, or combinations of these techniques. Short-term and long-term complications are more common after salvage RP than standard RP, partly because the normal anatomic planes are lost as a consequence of radiation. According to published series, up to 15 % of patients experienced rectal injuries although recent reports suggest the incidence in closer to 2 % [15]. Other early complications of surgery include ureteral transection, prolonged anastomotic leakage, and/or pulmonary embolism. Later complications include development of an anastomotic stricture or persistent urinary incontinence. The overall anastomotic stricture rate is as high as 30 % [15], and most patients who develop an anastomotic stricture will require multiple interventions. The development of an anastomotic stricture appears less likely in patients undergoing minimally invasive salvage RP than those undergoing an open procedure [15–19]. A review of published series suggests that the recovery of continence after salvage RP (both open and minimally invasive) has improved over time [6, 9, 15, 20], likely reflecting not only an improvement in surgical technique but also better targeted radiation therapies resulting in better preservation of the urinary sphincter.

Erectile dysfunction has been considered almost inevitable after salvage RP, but in selected cases this may be prevented by preservation of one or both neurovascular bundles. Stephenson et al. reported on a series of 100 consecutive patients with biopsy-confirmed, locally recurrent prostate cancer treated with salvage RP between 1984 and 2003. While overall postsurgical potency in that series was low (16 % [95 % CI, 4–28 %]), many patients had erectile dysfunction prior to salvage RP [15]. For men who were potent preoperatively, the 5-year recovery of potency was 45 % (95 % CI, 16–75 %). Of seven patients who underwent bilateral nerve-sparing procedures, five (71 %) recovered functional erections. Importantly, none of the seven had a positive surgical margin in the area where the neurovascular bundle was preserved.

Data on patterns of recurrence (local or metastatic) after salvage RP have been fairly limited. Several recent series, however, have demonstrated excellent oncologic outcomes after salvage RP (>90 % cancer-specific survival at 5 years) [5, 6, 8, 9, 20]. In a retrospective study by Paparel et al. of 146 patients treated with salvage RP at a single institution [8], the 5-year recurrence-free probability was 54 % (95 % CI, 44–63 %). Clinical local recurrence occurred in only one patient, who also had bone metastases. Sixteen patients died of prostate cancer and 19 died of other causes. The 5-year cumulative incidence of death due to prostate cancer was 4 % (95 % CI, 2–11 %). Serum PSA level and biopsy Gleason score before salvage RP were found to be significantly associated with death from prostate cancer (p < 0.0005 and p = 0.002, respectively).

Technique of Open Salvage Radical Prostatectomy

Salvage RP is curative only if the entire cancer is removed. Accurate preoperative assessment of the cancer allows the surgeon to plan an operation tailored to the size, location, and extent of the patient’s cancer, as well as the prostatic and periprostatic anatomy. Consideration of additional factors such as PSA levels, clinical stage, and the results of systematic needle biopsy increase the likelihood of successful treatment. Information about the location of positive biopsies, the length of cancer in each core, and the Gleason grade can help to characterize the location and extent of cancer within the prostate and surrounding tissues. Knowledge of the presence and location of any extraprostatic extension allows the surgeon to modify the operation by performing a wider excision in the involved area to decrease the risk of a positive surgical margin.

Patient Positioning and Initial Incision

The patient should be in a supine position (see Fig. 7.2), with the table flexed as needed to gain access to the pelvis. Sharply incise the transversalis fascia through an 8-cm suprapubic midline incision extending toward the umbilicus, and enter the retropubic space. Take care not to sweep perivesical lymph nodes cephalad as the lateral pelvic sidewalls are exposed. A self-retaining Turner Warwick retractor is effective in providing adequate pelvic exposure, although alternative retractors can be used as well. Insert an 18 Fr Foley catheter and fill the balloon with 10–15 cm3 of sterile water.

Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection

Patients undergoing salvage RP are at increased risk of nodal involvement compared to those undergoing standard RP [5, 6, 8, 9], and a pelvic lymph node dissection (PLND) at the time of RP is recommended for all such patients. There have been no prospective studies demonstrating the appropriate anatomical limits of a PLND for prostate cancer. However, lymphatic drainage of the prostate is known to be highly variable and involves regions not sampled during an obturator-only PLND [21]. Some surgeons resect only the external iliac lymph nodes unless imaging suggests abnormal lymph nodes in other regions, while other surgeons routinely perform a more extensive dissection that includes the obturator, external iliac, and hypogastric areas. When such an extended PLND is performed, not only are more nodes retrieved, but the lymph nodes from most of the potential landing zones are removed—significantly increasing the number of patients found to have lymph node invasion [21–23]. The extended dissection yields a higher lymph node count and detects more positive lymph nodes than a lymphadenectomy that is limited to the nodal tissue between the external iliac vein and top of the obturator nerve (external iliac area).

Mobilization of the Prostate and Control of the Dorsal Vein Complex

Mobilize the prostate by incising the endopelvic fascia laterally in the groove between the prostate and the levator ani muscles. Extend the fascial incision sharply toward the pelvis where the fascia condenses into the puboprostatic ligaments. Blunt dissection is inadequate during this procedure, as tissues are typically fused together. Using sharp dissection, further mobilize the prostate from the levator ani muscles. The puboprostatic ligaments need not be divided if the apex of the prostate is adequately exposed.

To prevent significant back bleeding, ligate the superficial dorsal vein complex at the bladder neck and suture-ligate the deep dorsal vein complex at the mid-prostate using a 0-polyglactin absorbable suture on a CT-1 needle (Fig. 9.2). The first suture marks the site of division of the bladder neck later in the operation. The suture at the level of the mid-prostate traverses the anterior surface of the gland from one cut edge of endopelvic fascia to the other. Placement of this stitch is facilitated by use of either a Babcock or Allis clamp to bunch the deep dorsal venous complex followed by a figure-of-eight suture beneath the closed clamp. This suture should not be placed too far laterally as this may injure the periprostatic veins and increase bleeding.

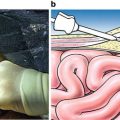

Fig. 9.2

The superficial dorsal vein complex (DVC) is suture ligated at the bladder neck, approximately 1 cm cephalad to the junction of the prostate and bladder (a, b). A deeper suture is placed around the superficial and deep DVC midway toward the apex, extending from one cut edge of endopelvic fascia to the other. Using a Babcock clamp to “bunch” this tissue together can facilitate placement of this suture. These sutures limit back bleeding on transection of the DVC. From Scardino PT, Linehan WM. Comprehensive Textbook of Genitourinnary Oncology. © 2011 Wolters Kluwer Health, used with permission

Next, pass a right-angle clamp through the fascia beneath the entire dorsal vein complex anterior to the urethra just distal to the prostatic apex (Fig. 9.3a). This clamp will be used to grasp a 22-gauge stainless steel wire looped on the end. Grasp the small loop in the wire with the right-angled clamp and bring it beneath the dorsal vein complex, then grasp the two ends of the wire with a Kelly or Cocker clamp. Use a third suture of 0-polyglactin absorbable suture on a CT-1 needle to control the deep dorsal venous complex at the pelvic floor. The wire (which has been placed anterior to the urethra) can be used as a guide to set the proper depth of this suture. Pass a second throw of this suture approximately halfway above the first throw, and then pass a third and final throw through the periosteum on the underside of the pubic bone. The final throw helps to crush the superficial dorsal veins between the pubis and the main dorsal vein complex. It also fixes the urethra in the pelvis, which may reduce urethral hypermobility.

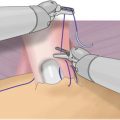

Fig. 9.3

A long-nosed right-angled clamp is passed through the fascia between the urethra and dorsal vein complex (DVC) and grasps a stainless steel wire that is looped on the end (a). The wire serves as a guide to allow a square transection of the DVC and its surrounding fascia (b). A sucker tip can be used to retract the apex of the prostate (c). By this maneuver the DVC can be divided close to or far from the apex of the prostate, as the surgeon chooses, with care to avoid a positive anterior surgical margin. A&B from Scardino PT, Linehan WM. Comprehensive Textbook of Genitourinnary Oncology. © 2011 Wolters Kluwer Health, used with permission. C used with permission from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center

The wire serves as a template when the complex is transected sharply with a No. 15 surgical blade on a long knife handle between the mid-prostate and pelvic floor dorsal venous complex sutures (Fig. 9.3b). Adjusting the upward tension on the wire and downward traction on the prostate with a sponge stick will enable division of the dorsal vein complex sufficiently far from the apex to minimize the risk of a positive anterior surgical margin. The dorsal vein complex must be divided sufficiently distal to the anterior prostate to avoid an anterior positive margin. A sucker tip placed on the prostatic apex can be used to further expose this area (Fig. 9.3c). Using a surgical wire to divide the dorsal vein complex will facilitate the anterior dissection of the prostate. To control bleeding from the dorsal vein complex, sew together the incised edges of the lateral pelvic fascia on either side of the complex using a continuous 00-polyglactin absorbable suture on a CT-2 needle (Fig. 9.4a). Finally, sew the suture through the periosteum of the pubis, compressing the superficial veins between the fascia and the pubic bone (Fig. 9.4b).