Chapter Outline

Metastases

Esophageal metastases are found at autopsy in less than 5% of patients dying of carcinoma. Most cases result from direct invasion by primary malignant tumors of the stomach, lung, and neck or from contiguous involvement by tumor-containing lymph nodes in the mediastinum. These various forms of esophageal involvement by metastatic tumor produce characteristic radiographic findings that are discussed separately in later sections.

Sites of Origin

Carcinoma of the stomach accounts for about 50% of all esophageal metastases. Tumors involving the gastric cardia or fundus may invade the distal esophagus by contiguous spread through the diaphragmatic hiatus. Carcinomas of the lung and breast are other less common causes of esophageal metastases. Most cases result from direct extension of tumor to the esophagus or from contiguous esophageal involvement by lymphadenopathy in the posterior mediastinum. The esophagus may also be involved by contiguous spread of malignant tumors in the neck, such as laryngeal, pharyngeal, and thyroid carcinomas. Rarely, the esophagus may be involved by hematogenous metastases from tumors arising in distant locations such as the kidney, liver, rectum, prostate, cervix, and skin. Thus, most malignant tumors are capable of metastasizing to the esophagus.

Clinical Findings

Patients with esophageal metastases may present with dysphagia as a result of esophageal compression by enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes or actual invasion of the esophagus by tumor. Although the presence of esophageal metastases usually indicates a poor prognosis, some patients (particularly those with breast or lung cancer) may present with dysphagia as the initial manifestation of their disease. Also, patients with breast cancer often have late-onset metastases to the esophagus, with an average interval of approximately 8 years from the time of diagnosis to the development of dysphagia. When dysphagia occurs, these patients usually have widespread metastatic disease.

Radiographic Findings

Direct Invasion

Direct invasion of the cervical or thoracic esophagus by carcinoma of the larynx, pharynx, thyroid, or lung produces characteristic findings on barium studies. Early invasion may be manifested by a smooth or slightly irregular indentation on the esophagus with gently sloping, obtuse borders and a contiguous soft tissue mass in the adjacent mediastinum or neck. The area of involvement may have a more serrated, scalloped, or nodular appearance as the esophageal wall is further infiltrated by tumor ( Fig. 24-1 ). Eventually, there may be circumferential narrowing of the esophagus with mass effect, nodularity, ulceration, or obstruction ( Fig. 24-2 ). Rarely, thyroid cancer invading the esophagus may be manifested by an expansile intraluminal mass, mimicking the appearance of a spindle cell carcinoma (see later, “ Spindle Cell Carcinoma ”).

Secondary esophageal involvement by carcinoma of the gastric cardia or fundus may be manifested radiographically by a polypoid mass extending from the fundus into the distal esophagus ( Fig. 24-3 ) or by irregular narrowing of the distal esophagus without a discrete mass. Esophageal involvement is usually confined to a short segment of the distal esophagus but may extend as far proximally as the aortic arch. Occasionally, these tumors may cause smooth, tapered narrowing of the distal esophagus at or near the gastroesophageal junction, mimicking the appearance of achalasia (see later, “ Secondary Achalasia ”).

When the distal esophagus appears to be involved by tumor on barium studies, the gastric cardia and fundus should also be evaluated radiographically to determine whether there is associated gastric involvement. In some cases, barium studies may demonstrate an obvious malignant tumor in the stomach (see Fig. 24-3 ). In others, however, the presence of tumor in the gastric fundus may be recognized only by distortion or obliteration of the normal anatomic landmarks at the cardia associated with relatively subtle areas of nodularity, mass effect, or ulceration ( Fig. 24-4 ). Thus, a meticulous double-contrast examination of the fundus is essential to rule out an underlying carcinoma of the cardia in these patients.

Contiguous Involvement by Mediastinal Lymph Nodes

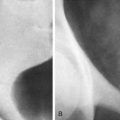

Although any neoplasm that metastasizes to mediastinal lymph nodes may secondarily involve the esophagus, breast and lung cancer are the most common underlying malignant tumors in these patients. Because of the proximity of the midesophagus to subcarinal lymph nodes, esophageal involvement by mediastinal lymphadenopathy usually occurs at this level. Barium studies typically reveal a smooth or slightly lobulated extrinsic indentation on the esophagus at or just below the carina ( Fig. 24-5A ). When tumor directly invades the esophagus, it may have a more irregular contour, often with areas of ulceration ( Fig. 24-6 ). Eventually, the esophageal wall may be circumferentially infiltrated by tumor, producing an area of concentric narrowing with a surrounding soft tissue mass ( Fig. 24-7 ). When esophageal involvement by mediastinal tumor is suspected on barium studies, CT should be performed to show the location and extent of lymphadenopathy in the mediastinum ( Fig. 24-5B ).

Hematogenous Metastases

True blood-borne or hematogenous metastases to the esophagus are extremely uncommon. Most cases are caused by carcinoma of the breast, but other distant tumors may also metastasize hematogenously to the esophagus. Surprisingly, however, malignant melanoma (which has the highest percentage of blood-borne metastases to the gastrointestinal tract) rarely involves the esophagus. Whatever the origin, blood-borne metastases to the esophagus usually appear on barium studies as short, eccentric strictures (usually in the middle third of the esophagus) with intact overlying mucosa and smooth, tapered margins ( Fig. 24-8 ). Although blood-borne metastases to the esophagus tend to be infiltrating lesions, they occasionally may be manifested by one or more discrete submucosal masses or centrally ulcerated bull’s-eye lesions.

Differential Diagnosis

A smooth or slightly lobulated indentation on the esophagus may be caused by a variety of extrinsic mass lesions such as benign tumors and cysts in the mediastinum, aberrant vessels, and an ectatic aorta or aortic aneurysm compressing the esophagus. In contrast, esophageal invasion by metastatic tumor should be suspected when the area of mass effect has an irregular, serrated, or nodular contour or is associated with ulceration. As a result, malignant invasion of the esophagus usually can be distinguished from benign lesions in the mediastinum that are compressing but not invading the esophagus.

The differential diagnosis for upper or midesophageal strictures caused by metastatic tumor includes Barrett’s esophagus and scarring from mediastinal irradiation, caustic ingestion, eosinophilic esophagitis, or oral medications such as potassium chloride and quinidine. When these patients are known to have a previously irradiated malignant tumor in the thorax, the major diagnostic considerations include a benign radiation stricture and recurrent tumor. In such cases, computed tomography (CT) may be used to differentiate recurrent tumor from a radiation stricture by showing a mediastinal mass or lymphadenopathy in the region of the stricture.

Secondary Achalasia

The terms secondary achalasia and pseudoachalasia are used interchangeably to describe an entity in which the clinical, radiographic, endoscopic, and manometric features may be indistinguishable from those of primary, or idiopathic, achalasia. Malignancy-induced secondary achalasia is an uncommon condition, accounting for only 2% to 4% of patients with findings of achalasia at manometry. Almost 75% of cases are caused by carcinoma of the gastric cardia or fundus directly invading the gastroesophageal junction or distal esophagus. Less frequently, hematogenous metastases from other malignant tumors such as breast, lung, pancreatic, uterine, and prostate cancer or even lymphoma involving the gastroesophageal junction may produce identical findings. Other benign causes of secondary achalasia include Chagas’ disease, amyloidosis, and Nissen fundoplication. It is important to differentiate primary and secondary achalasia because primary achalasia may be treated by pneumatic dilation, botulinum toxin injection, or laparoscopic myotomy, whereas secondary achalasia often necessitates chemotherapy or other treatment for widespread metastatic disease.

Pathogenesis

Primary and secondary achalasia are characterized by absent esophageal peristalsis and a hypertensive lower esophageal sphincter that fails to relax normally in response to deglutition. In patients with primary achalasia, the motor disorder is thought to be caused by degeneration and loss of the ganglion cells of Auerbach’s plexus in the esophagus. However, the precise mechanism whereby metastases produce this motility disorder is uncertain. Some patients have tumor directly invading the distal esophagus with actual destruction of myenteric ganglia. However, others have tumor confined to the gastroesophageal junction without involvement of the neural plexus in the esophagus. In such cases, the motor disorder may be caused by extraesophageal metastases to the vagus nerve or dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve in the brain stem. Secondary achalasia may also occur as a paraneoplastic phenomenon caused by circulating tumor products that alter esophageal motor function. Finally, malignant neuroendocrine tumors (particularly small cell carcinoma of the lung) may express a variety of neural antigens that initiate an autoimmune response with circulating antibodies—known as anti-Hu antibodies—that cause neural degeneration and secondary achalasia.

Clinical Findings

Although dysphagia occurs in primary and secondary achalasia, various clinical features are helpful for distinguishing these entities. Most patients with primary achalasia are between 20 and 50 years of age, and they have dysphagia for a mean duration of 4 to 6 years before seeking medical attention. In contrast, most patients with secondary achalasia are more than 60 years of age, and the duration of symptoms is usually less than 6 months. Secondary achalasia also is far more likely to be associated with weight loss. An underlying malignant tumor should therefore be suspected whenever achalasia is diagnosed in older patients with recent onset of dysphagia and weight loss. Nevertheless, some patients with primary achalasia may be older than 60 years and others may have a relatively short duration of symptoms. Thus, it is not always possible to differentiate these conditions on clinical grounds.

Radiographic Findings

Secondary achalasia is classically manifested on barium studies by absent esophageal peristalsis and smooth, tapered narrowing of the distal esophagus, producing a bird-beak configuration at or abutting the gastroesophageal junction ( Fig. 24-9 ). Although the radiographic appearance may closely resemble that of primary achalasia, infiltration of the distal esophagus by tumor in secondary achalasia sometimes causes asymmetric or eccentric narrowing, abrupt transitions, rigidity, and mucosal nodularity or ulceration. Another important sign of malignancy is the length of the narrowed segment, which may extend 3.5 cm or more above the gastroesophageal junction in secondary achalasia ( Fig. 24-10 ) but rarely extends this far proximally in patients with primary achalasia. Finally, the degree of esophageal dilation is usually less in patients with secondary achalasia because of the rapid onset of disease. When findings of achalasia are present on barium studies, a narrowed distal esophageal segment longer than 3.5 cm with little or no proximal dilation in an older patient with recent onset of dysphagia should therefore be highly suggestive of secondary achalasia, even in the absence of other suspicious radiographic findings.

Because secondary achalasia is usually caused by carcinoma of the gastric cardia or fundus invading the distal esophagus, careful radiologic evaluation of the fundus is essential in these patients. Not infrequently, an obvious polypoid, ulcerated, or infiltrating carcinoma may be demonstrated in the fundus (see Fig. 24-9B ). With less advanced lesions, no gross abnormalities may be demonstrated in the gastric fundus on conventional single-contrast barium studies. However, double-contrast studies may reveal subtle evidence of tumor distorting or obliterating the normal anatomic landmarks at the gastric cardia (see Fig. 24-10 ). In contrast, the characteristic rosette that demarcates the gastric cardia on double-contrast studies should be normal in patients with primary achalasia.

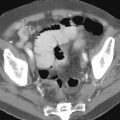

CT is often helpful for differentiating primary and secondary achalasia. Patients with primary achalasia typically have little or no gastric esophageal wall thickening ( Fig. 24-11A ) and no evidence of mediastinal lymphadenopathy or a mass at the cardia on CT ( Fig. 24-11B ). In some cases, however, CT may reveal a pseudomass at the cardia because of inadequate distention of this region. In contrast, patients with secondary achalasia often have a thickened wall in the distal esophagus on CT, and the thickened wall tends to be lobulated and asymmetric ( Fig. 24-12A ). CT may also reveal a soft tissue mass at the cardia ( Fig. 24-12B ), mediastinal lymphadenopathy, and the presence of pulmonary, pleural, or hepatic metastases. CT is also helpful for detecting the site of the primary tumor in patients with secondary achalasia caused by carcinoma of the gastric cardia or fundus, lung, or pancreas or other malignant neoplasms in the chest or abdomen.

Lymphoma

The esophagus is the least common site of gastrointestinal involvement by lymphoma, accounting for only about 1% of cases. Both non-Hodgkin’s and, less commonly, Hodgkin’s lymphoma may involve the esophagus. These patients almost always have generalized lymphoma with direct invasion of the esophagus by lymphomatous nodes in the mediastinum, contiguous spread of lymphoma from the gastric fundus, or synchronous development of lymphoma in the esophagus. Rarely, primary esophageal lymphoma (usually Hodgkin’s lymphoma) may occur without extraesophageal disease. Cases of AIDS-related primary esophageal lymphoma have also been reported. When esophageal lymphoma is suspected, endoscopy should be performed with deep esophageal biopsy specimens to confirm the diagnosis. However, false-negative biopsy specimens have been reported in 25% to 35% of cases because of the patchy nature of the disease and sampling error. Thus, some patients may require surgery for a definitive diagnosis.

Clinical Findings

Most patients with esophageal lymphoma have no esophageal symptoms, so the diagnosis is usually made at autopsy in patients with widespread disease. However, some patients may develop dysphagia as a result of esophageal narrowing or obstruction by tumor. Rarely, they may present with dysphagia as the initial manifestation of their disease.

Radiographic Findings

Secondary involvement of the esophagus by gastric lymphoma may be manifested on barium studies by irregular narrowing of the distal esophagus caused by contiguous spread of tumor from the gastric fundus ( Fig. 24-13 ). In such cases, careful radiologic examination of the gastric cardia and fundus may demonstrate a polypoid, ulcerated, or infiltrating lesion in the fundus secondary to the underlying gastric lymphoma. Transcardiac extension of gastric lymphoma is thought to occur in about 10% of patients. However, these lesions cannot be distinguished radiographically from carcinoma of the gastric fundus invading the distal esophagus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree