Chapter Outline

Malignant Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor

Metastases

Gastric metastases are found at autopsy in less than 2% of patients who die of carcinoma. Duodenal metastases are even rarer. Nevertheless, metastases to the stomach and duodenum have been encountered more frequently as combined treatment with surgery, radiation, and/or chemotherapy has led to prolonged survival of patients with widespread metastatic disease. Most lesions are hematogenous metastases from malignant melanoma or carcinoma of the breast or lung. Less frequently, the stomach or duodenum may be involved by lymphatic spread of tumor or by direct extension of tumor from neighboring structures or mesenteric reflections such as the gastrocolic ligament, transverse mesocolon, and greater omentum. These various forms of spread produce characteristic radiographic findings that are considered separately in the following sections.

Clinical Findings

Most gastroduodenal metastases are discovered unexpectedly at surgery or autopsy. However, some patients with ulcerated metastases may develop signs or symptoms of upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, such as hematemesis, melena, and guaiac-positive stool. Others may present with epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, early satiety, anorexia, or weight loss. One or more of these findings are sometimes caused by systemic chemotherapy or the hypercalcemia associated with widespread metastatic disease. As a result, gastroduodenal metastases may not be suspected, even if symptoms are present.

Most patients with gastroduodenal metastases have a known underlying malignancy. Occasionally, however, metastases to the stomach or duodenum may occur as the initial manifestation of an occult primary tumor. Certain malignancies such as carcinoma of the breast and kidney can also metastasize to the stomach or duodenum many years after treatment of the original lesion. It is therefore important to obtain a detailed clinical history in these patients.

Radiographic Findings

Hematogenous Metastases

True hematogenous or blood-borne metastases to the stomach or duodenum may be caused by a variety of malignant tumors. Although malignant melanoma has the highest percentage of hematogenous metastases to the GI tract, breast cancer is such a common disease that it rivals melanoma as the most common cause of metastases to the bowel. Much less frequently, the stomach or duodenum may be involved by hematogenous metastases from thyroid or testicular carcinoma or from other remote tumors.

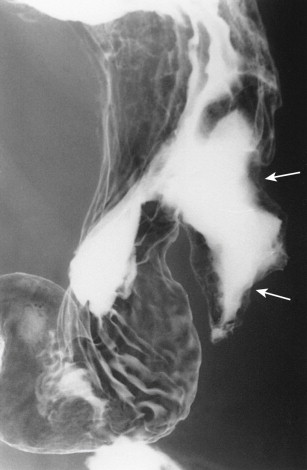

Hematogenous metastases usually appear on barium studies as one or more discrete submucosal masses in the stomach, duodenum, or small intestine ( Fig. 33-1 ). When multiple lesions are present, they tend to be of varying sizes because of periodic showers of tumor emboli into the arterial supply of the bowel. As these submucosal masses outgrow their blood supply, they may undergo central necrosis and ulceration, resulting in the development of classic “bull’s-eye” or “target” lesions ( Fig. 33-2 ). In general, bull’s-eye lesions have large central ulcers in relation to the size of the surrounding mass. Superficial fissures may occasionally radiate toward the central ulcer crater, producing a characteristic spoke wheel pattern (see Fig. 33-2B ).

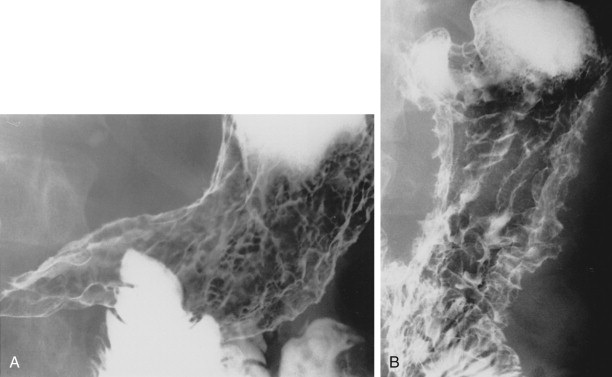

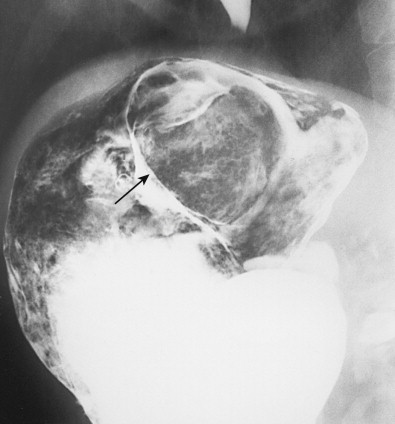

Hematogenous metastases to the stomach or duodenum are sometimes manifested by larger, more lobulated masses that can be mistaken radiographically for malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) or even polypoid carcinomas ( Fig. 33-3 ). Other metastases, particularly those from malignant melanoma, may become necrotic, resulting in the development of giant cavitated lesions. These cavitated metastases can be recognized on barium studies as amorphous collections of barium (usually ranging from 5-15 cm in size) that communicate with the lumen ( Fig. 33-4 ). Computed tomography (CT) is particularly well suited for demonstrating these giant cavitated lesions.

Hematogenous metastases to the stomach from breast cancer may produce a linitis plastica or “leather bottle” appearance indistinguishable from that of a primary scirrhous carcinoma of the stomach ( Fig. 33-5 ). This linitis plastica appearance is caused not by fibrosis (as in patients with scirrhous carcinoma) but by highly cellular infiltrates of metastatic tumor in the gastric wall. Although the degree of luminal narrowing is variable, these lesions can still be recognized on double-contrast studies by distortion of the normal surface pattern of the stomach with mucosal nodularity, spiculation, ulceration, or thickened, irregular folds (see Fig. 33-5 ). Some of these tumors may involve the proximal portion of the stomach with sparing of the antrum (see Fig. 33-5B ). The possibility of metastatic disease should therefore be considered in any patient with linitis plastica who has a history of breast carcinoma.

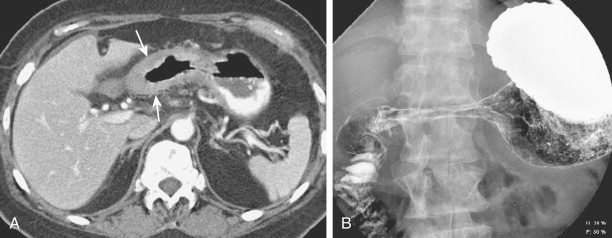

Metastatic disease to the stomach is usually found on CT studies performed as part of the routine work-up of patients with known malignant tumors. Although many extragastric tumors can metastasize to the stomach, careful evaluation of the stomach is particularly important in patients with known malignant melanoma or breast or lung cancer. It has been found that metastatic breast cancer involves the stomach in 5% to 27% of patients, often causing extensive gastric wall thickening (sometimes associated with increased attenuation of the wall after intravenous [IV] contrast enhancement) that simulates the linitis plastica appearance of a scirrhous gastric cancer ( Fig. 33-6 ). In other patients, CT may demonstrate more focal wall thickening ( Fig. 33-7 ). Because these tumors often reside deeply within the gastric wall, it can be difficult to obtain a definitive pathologic diagnosis from endoscopic biopsy specimens. Nevertheless, in the proper clinical setting, CT findings should be highly suggestive of metastatic breast cancer involving the stomach.

Hematogenous metastases to the stomach from malignant melanoma, bronchogenic carcinoma, and Kaposi’s sarcoma may also be detected on CT.

Lymphatic Spread

Gastric metastases are found at autopsy in 2% to 15% of patients who die of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. These metastases are thought to be caused by tumor emboli that seed the gastric cardia or fundus via submucosal esophageal lymphatics extending subdiaphragmatically to paracardiac, lesser curvature, and celiac nodes. Squamous cell metastases to the gastric fundus may appear on barium studies as giant submucosal masses, often containing central areas of ulceration ( Fig. 33-8 ). As a result, these lesions can be mistaken for benign or malignant GISTs or even adenocarcinomas. Squamous cell metastases to paracardiac or other lymph nodes in the upper abdomen are sometimes recognized on CT scans as low-attenuation masses relative to skeletal muscle ( Fig. 33-9 ).

The duodenum is occasionally involved by peripancreatic lymphadenopathy from pancreatic carcinoma, lymphoma, or other malignant tumors. In such cases, barium studies may reveal nodular indentations on the medial border of the descending duodenum or widening of the duodenal sweep. However, pancreatic carcinoma, pancreatic pseudocysts, and pancreatitis can produce identical radiographic findings. CT is extremely helpful for determining the cause of a widened duodenal sweep and for differentiating a pancreatic mass from adjacent lymphadenopathy.

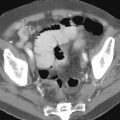

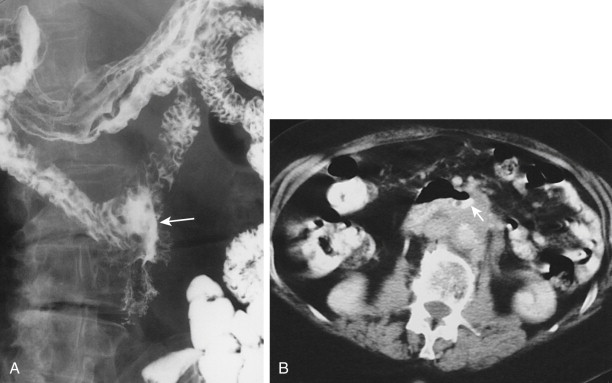

Malignant tumors that metastasize to retroperitoneal lymph nodes near the superior mesenteric root may be manifested on barium studies by extrinsic mass effect, nodular indentations, ulceration, or, in advanced cases, obstruction of the distal duodenum near the ligament of Treitz ( Fig. 33-10A ). CT is ideally suited for demonstrating retroperitoneal adenopathy as the cause of these abnormalities ( Fig. 33-10B ). Occasionally, retroperitoneal tumor involving the duodenum may cause delayed gastric emptying and massive gastric dilation out of proportion to the degree of duodenal dilation ( Fig. 33-11 ). This disproportionate gastric dilation is probably related to vagal destruction by retroperitoneal tumor, which decreases gastric peristalsis and exacerbates gastric distention.

Direct Invasion

The stomach and duodenum may be directly invaded by malignant tumors arising in neighboring structures such as the esophagus, pancreas, and kidney. The stomach and duodenum may also be involved by direct extension of colonic carcinoma along mesenteric reflections (including the gastrocolic ligament and transverse mesocolon) or by contiguous spread of tumor from the greater omentum. Because the radiographic findings depend on the pathways of spread, the various primary malignant tumors are discussed separately in the following sections.

Esophageal Carcinoma.

In contrast to squamous cell carcinomas of the esophagus, adenocarcinomas arising in Barrett’s mucosa have a marked tendency to invade the gastric cardia or fundus. Gastric involvement may be manifested on barium studies by a large polypoid or ulcerated mass in the gastric fundus. In other cases, however, double-contrast views of the fundus may reveal more subtle findings, with distortion or obliteration of the normal anatomic landmarks at the cardia (the cardiac rosette) and irregular areas of ulceration or nodularity (see Chapter 23 ). It is sometimes difficult to determine whether these tumors at the gastroesophageal junction have arisen in the esophagus or stomach. In general, however, esophageal adenocarcinomas have a disproportionate degree of esophageal involvement in relation to that of the stomach, whereas gastric or cardiac carcinomas have a greater degree of fundal involvement.

Pancreatic Carcinoma.

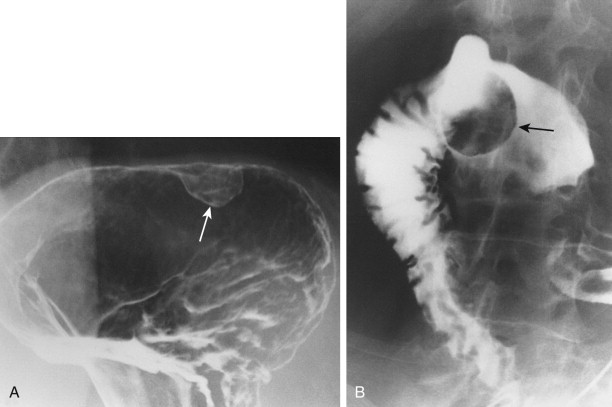

The radiographic manifestations of gastroduodenal involvement by pancreatic carcinoma depend on whether the underlying tumor is located in the head, body, or tail of the pancreas. Carcinoma of the pancreatic head may cause widening of the duodenal sweep or extrinsic compression of the medial border of the descending duodenum or greater curvature of the gastric antrum, whereas carcinoma of the pancreatic body or tail may cause extrinsic compression of the posterior wall of the gastric fundus and body or the superior border of the distal duodenum near the ligament of Treitz. Invasion of the stomach or duodenum may be manifested on barium studies by spiculated mucosal folds, nodularity, mass effect, ulceration, obstruction or, rarely, fistula formation ( Figs. 33-12 to 33-14 ).

Many patients with suspected pancreatic neoplasms undergo CT as the initial diagnostic examination. Although CT is of limited value in predicting minimal duodenal invasion by pancreatic carcinoma, distention of the duodenum with gas or water can facilitate detection of subtle findings of invasion. CT is of greater value in determining the cause of an abnormal retrogastric impression because it can differentiate pancreatic carcinoma from pancreatic pseudocysts ( Fig. 33-15 ), retrogastric varices, or other abnormalities in the retroperitoneum compressing the stomach.

Renal Cell Carcinoma.

Direct invasion of the duodenum by right-sided renal cell carcinoma may be manifested on barium studies by mass effect, nodularity, or ulceration of the right posterolateral border of the descending duodenum. However, renal cell carcinoma tends not to elicit a desmoplastic response in the wall of the bowel, so duodenal involvement is sometimes manifested by a polypoid intraluminal mass, mimicking the appearance of a primary duodenal carcinoma. In patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma, CT is useful for determining the extent of tumor and its proximity to the duodenum. When a contiguous lesion is identified, however, CT is not reliable for determining whether tumor is invading the duodenum.

Colonic Carcinoma.

Colonic carcinoma may involve the stomach or duodenum by direct extension along mesenteric reflections such as the gastrocolic ligament or transverse mesocolon. The gastrocolic ligament is the proximal portion of the greater omentum that extends superiorly from the anterosuperior border of the transverse colon to the greater curvature of the stomach ( Fig. 33-16 ). Because of this anatomic relationship, carcinoma of the transverse colon may invade the stomach via the gastrocolic ligament, producing mass effect, nodularity, and spiculated tethered folds on the greater curvature of the gastric antrum or body. In other patients, carcinoma of the ascending colon or hepatic flexure may invade the duodenum via the lateral reflection of the transverse mesocolon, producing mass effect, nodularity, ulceration, or spiculated folds on the lateral border of the descending duodenum ( Fig. 33-17A ). In such cases, a barium enema examination may show the underlying colonic neoplasm responsible for these findings, and CT may show the mode of spread to the stomach or duodenum ( Fig. 33-17B ).

Carcinoma of the transverse colon invading the stomach or carcinoma of the hepatic flexure invading the duodenum may occasionally lead to the development of a gastrocolic or duodenocolic fistula (see Chapter 34 ). In today’s pill-oriented society, however, most such fistulas are caused by aspirin-induced or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)–induced greater curvature ulcers that penetrate via the gastrocolic ligament into the transverse colon (see Chapter 29 ).

Gallbladder Carcinoma.

Advanced carcinoma of the gallbladder may directly invade adjacent structures such as the liver, duodenum, and hepatic flexure of the colon. Duodenal involvement by tumor has been reported in about 20% of patients. CT is particularly useful for showing gastric and duodenal invasion by tumor ( Fig. 33-18 ).

Omental Metastases.

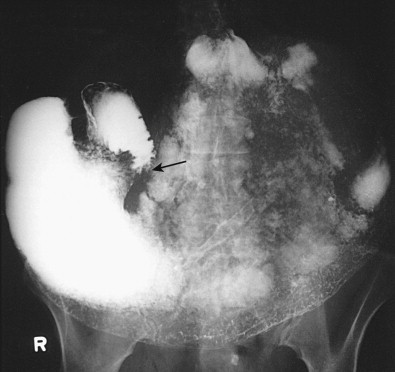

Bulky metastatic deposits in the greater omentum, or so-called omental cakes, usually result from widespread intraperitoneal dissemination of ovarian carcinoma or, less frequently, cervical, uterine, bladder, gastric, colonic, pancreatic, or breast carcinoma. These omental deposits may spread superiorly to the stomach via the proximal portion of the greater omentum, also known as the gastrocolic ligament (see Fig. 33-16 ). Gastric involvement by omental metastases is characterized on barium studies by mass effect, nodularity, flattening, or spiculated, tethered folds on the greater curvature of the gastric antrum or body ( Fig. 33-19A ). These changes reflect serosal involvement by tumor and a desmoplastic response that occurs along the insertion of the gastrocolic ligament on the greater curvature. In advanced cases, there may be circumferential narrowing of the gastric antrum resulting from encasement by metastatic tumor.

Carcinoma of the transverse colon invading the stomach via the gastrocolic ligament may produce identical radiographic findings (see earlier, “Colonic Carcinoma”). In such cases, however, a barium enema examination should demonstrate the primary colonic carcinoma responsible for these findings. In contrast, patients with omental metastases involving the stomach almost always have associated colonic involvement by omental tumor, with mass effect, nodularity, and spiculated folds on the superior border of the transverse colon ( Fig. 33-19B ) or, in advanced cases, circumferential narrowing of the bowel. In our experience, gastric involvement by omental metastases is far more common than gastric invasion by colonic carcinoma via the gastrocolic ligament.

When gastric involvement by omental metastases is suspected on barium studies, CT is extremely helpful for delineating the extent of metastatic tumor. Although barium studies provide indirect evidence of omental tumor, CT can reveal omental masses as small as 1 cm in diameter. More extensive omental metastases may be manifested on CT by a spectrum of findings, ranging from a lacy reticular appearance to bulky masses. Non-neoplastic processes involving the omentum (notably tuberculous peritonitis) can simulate omental tumor. When the greater omentum is diffusely infiltrated by tumor, an omental cake may displace the colon or small bowel from the anterior abdominal wall ( Fig. 33-19C ). Unless the lumen of the bowel is distended with contrast medium or gas, however, it is difficult to determine whether tumor is invading the stomach or transverse colon.

Differential Diagnosis

Hematogenous metastases that appear as small nodular lesions in the stomach or duodenum may be difficult to differentiate on barium studies from multiple hyperplastic or adenomatous polyps. Metastases that have a more typical submucosal appearance can be mistaken for benign intramural lesions such as GISTs, lipomas, or ectopic pancreatic rests. However, these benign mesenchymal tumors tend to occur as solitary lesions, whereas metastases are usually multiple. Centrally ulcerated bull’s-eye lesions may be caused not only by hematogenous metastases but also by lymphoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma, or carcinoid tumors. Occasionally, varioliform erosions surrounded by unusually prominent mounds of edema can be mistaken for bull’s-eye lesions. However, varioliform erosions are rarely larger than 1 cm, and the central barium collections are considerably smaller than those seen in ulcerated submucosal masses.

Giant cavitated lesions in the stomach and duodenum may be caused not only by metastatic disease (particularly malignant melanoma) but also by lymphoma or malignant GISTs. However, malignant GISTs tend to occur as solitary lesions, so the presence of multiple cavitated masses in the stomach, duodenum, or small bowel should favor a diagnosis of metastatic disease or lymphoma.

The linitis plastica appearance caused by metastatic breast cancer may be indistinguishable on barium studies from that of a primary scirrhous carcinoma of the stomach. Circumferential gastric involvement by pancreatitis, pancreatic carcinoma, colonic carcinoma, omental metastases, lymphoma, or Crohn’s disease and scarring from various types of severe gastritis may produce similar findings. Nevertheless, the possibility of metastatic disease should be considered when a linitis plastica appearance is detected in patients who were previously treated for breast cancer.

Direct invasion of the stomach and duodenum by metastatic tumor may be simulated by various benign and malignant conditions in the upper abdomen. Compression or displacement of the greater curvature or posterior wall of the stomach or of the medial border of the descending duodenum may be caused not only by pancreatic carcinoma but also by pancreatitis, pancreatic pseudocysts (see Fig. 33-15 ), peripancreatic lymphadenopathy, abdominal aortic aneurysms, or other retroperitoneal processes. Various signs of bowel wall invasion (e.g., mass effect, nodularity, and spiculated, tethered folds) may also result from a nonspecific desmoplastic response to inflammatory conditions involving the stomach. Thus, pancreatitis may produce changes on the greater curvature that are impossible to distinguish from pancreatic or colonic carcinoma or omental metastases involving the stomach. Other imaging techniques such as CT are usually helpful for differentiating these conditions.

Lymphoma

Lymphoma involves the stomach more frequently than any other portion of the gastrointestinal tract. Gastric lymphoma accounts for 50% of all GI lymphomas, 25% of all extranodal lymphomas, and 3% to 5% of all malignant tumors in the stomach. More than 50% of patients with gastric lymphoma have localized disease that is confined to the stomach and regional lymph nodes (primary gastric lymphoma); the remainder have generalized lymphoma with associated gastric involvement (secondary gastric lymphoma). When it occurs, duodenal lymphoma usually results from contiguous transpyloric spread of lymphoma from the stomach. Because of its rarity, duodenal lymphoma is considered separately in a later section.

The vast majority of gastric lymphomas are non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas of B-cell origin. There is considerable evidence that these lymphomas arise from mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) occurring in patients with chronic Helicobacter pylori gastritis. It has therefore been postulated that most primary non-Hodgkin’s gastric lymphomas originate as low-grade MALT lymphomas, which, if untreated, eventually progress to more high-grade lymphomas. In the past, low-grade proliferation of lymphoid tissue in the stomach was sometimes known as pseudolymphoma. However, these pseudolymphomas are currently thought to represent monoclonal B-cell proliferations or true B-cell MALT lymphomas. As a result, the term pseudolymphoma has largely been abandoned.

Because the gross pathologic findings are nonspecific, gastric lymphoma is often difficult to differentiate from gastric carcinoma on radiologic or endoscopic examination. However, gastric lymphoma has a much better prognosis than gastric carcinoma, with overall 5-year survival rates of 50% to 60%. Thus, failure to obtain biopsy specimens from an advanced lesion that is assumed to be inoperable gastric cancer may deprive the patient of the opportunity for cure or long-term palliation. Proper staging of the tumor is also important, so a rational decision can be made about treatment options such as surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy.

Pathology

The vast majority of gastric lymphomas are non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Only rarely are these patients found to have Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Because of confusion with prior classification systems, pathologists at the National Cancer Institute have developed a working formulation that recognizes three prognostic categories of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma—low grade, intermediate grade, and high grade. Advanced lesions are usually classified as high-grade lymphomas of the large cell or immunoblastic type.

The literature suggests that most primary non-Hodgkin’s gastric lymphomas are low-grade B-cell lymphomas that arise from MALT. These lesions have been classified as marginal zone B-cell MALT lymphomas by the International Lymphoma Study Group. Paradoxically, these low-grade MALT lymphomas often occur in the stomach, which normally contains no organized lymphoid tissue. However, it has been well documented that chronic H . pylori gastritis leads to the acquisition of lymphoid follicles and aggregates in the lamina propria (MALT) and the subsequent development of low-grade, B-cell MALT lymphomas. Studies have also suggested that almost all patients with low-grade MALT lymphomas have particular strains of H . pylori containing the cytotoxin-associated gene A (cagA), so these strains may have an important role in the pathogenesis of gastric MALT lymphoma.

Gastric MALT lymphomas are manifested pathologically by infiltration of the epithelium with small centrocyte-like cells, giving rise to the lymphoepithelial lesions characteristic of these tumors. In various series, MALT lymphomas have been found to constitute as many as 50% to 72% of all primary gastric lymphomas, so this is a more common tumor than was previously recognized.

It has been shown that regions of low-grade MALT lymphoma are present on histopathologic examination in approximately 30% of patients with high-grade gastric lymphoma. The findings from these studies support the concept that most non-Hodgkin’s gastric lymphomas originate as low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas, which subsequently undergo transformation to intermediate- or high-grade lymphomas. These low-grade MALT lymphomas could therefore be considered to be a form of early gastric lymphoma, defined as lymphoma limited to the mucosa or submucosa of the gastric wall, regardless of the presence or absence of lymph node metastases.

Primary gastric lymphoma is usually confined to the stomach or regional lymph nodes at the time of diagnosis. In the Ann Arbor staging system, stage IE lesions involve the gastric wall, stage IIE lesions involve regional lymph nodes in the abdomen, stage III lesions involve lymph nodes above and below the diaphragm, and stage IV lesions are widely disseminated lymphomas that involve extra-abdominal lymph nodes and the omentum, mesentery, peritoneum, liver, spleen, lungs, or brain. The major factors affecting survival of patients with primary gastric lymphoma are the depth of invasion of the gastric wall and presence or absence of nodal disease.

Clinical Findings

Gastric lymphoma occurs more frequently in men than in women, and the average age at the time of diagnosis is 55 to 60 years. Patients with advanced lesions may present with abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, weight loss, a palpable epigastric mass, or signs of upper GI bleeding. Occasionally, these patients may develop an acute abdomen because of spontaneous perforation of an ulcerated gastric lymphoma or perforation complicating systemic chemotherapy. Patients with generalized lymphoma may also present with a fever or other signs of systemic disease. Whether or not affected individuals have primary gastric lymphoma or generalized lymphoma with gastric involvement, these lesions are often quite extensive in relation to the clinical presentation. Gastric lymphoma should therefore be suspected when a relatively advanced lesion in the stomach is associated with a paucity of clinical complaints.

In contrast to patients with early gastric cancer, who are usually asymptomatic (see Chapter 32 ), patients with early gastric lymphoma (particularly those with low-grade B-cell MALT lymphoma) may present with epigastric pain, dyspepsia, bloating, nausea, and/or vomiting. The symptoms at presentation are therefore indistinguishable from those caused by gastric or duodenal ulcers, gastritis, or duodenitis. Some patients may have underlying H . pylori gastritis as the cause of their symptoms. Whatever the explanation, the development of symptoms provides an opportunity to diagnose these low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas before they progress to more advanced lesions.

Endoscopic Findings

Low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas may be manifested at endoscopy by shallow ulcers, polypoid lesions, or erythematous, nodular mucosa. In contrast, high-grade lymphomas may be manifested by enlarged rugal folds, infiltrative masses, or nodular, polypoid, or ulcerated lesions in the stomach. Occasionally, endoscopy may reveal a characteristic volcano crater, with a discrete ulcer surrounded by a narrow ridge of tumor. Depending on the endoscopic findings, gastric lymphomas may be difficult to differentiate from carcinomas, benign GISTs, metastatic tumor, Ménétrier’s disease, hypertrophic gastritis, or even benign gastric ulcers. Endoscopic biopsy specimens are therefore required for a definitive diagnosis. Superficial biopsy specimens may be nondiagnostic because lymphomas often infiltrate the gastric wall beneath an intact mucosa. Whenever possible, multiple brushings and biopsy specimens should therefore be obtained from ulcerated or polypoid areas in which tumor is more likely to be present. Deep biopsy specimens should also be obtained when the overlying mucosa appears normal. With adequate cytologic and biopsy specimens, endoscopy has a reported sensitivity of 85% to 95% in diagnosing gastric lymphoma.

Treatment and Prognosis

When the diagnosis of gastric lymphoma has been established, proper staging of the tumor is needed to determine the appropriate treatment and assess prognosis. Additional diagnostic examinations include chest radiography, chest and abdominal CT scans, and 18 F-fluorodeoxyglucose ( 18 F-FDG)-labeled PET/CT imaging. When CT and 18 F-FDG-PET/CT scans are normal, routine staging laparotomy is probably unnecessary.

Many investigators think that the best treatment for early or localized gastric lymphoma with or without regional lymph node involvement (stage IE or IIE lesions) is a subtotal gastrectomy with postoperative radiation or chemotherapy. *

* See references .

Although the role of systemic chemotherapy for localized gastric lymphoma remains controversial, advanced gastric lymphoma (stage III or IV lesions) is sometimes treated by radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or both, without a gastric resection. Massive upper GI bleeding or even gastric perforation may occur as a complication of systemic chemotherapy, resulting in treatment failures.In contrast to high-grade gastric lymphomas, low-grade MALT lymphomas can often be treated successfully by combination therapy with proton pump inhibitors. In various studies, complete or partial regression of tumor has been reported in 60% to 80% of patients after eradication of H . pylori from the stomach. One theory is that H . pylori evokes an immunologic response that stimulates growth of the tumor. Whatever the explanation, eradication of H . pylori from the stomach with antibiotics appears to be a viable alternative to surgery, radiation, or chemotherapy as a first-line treatment for low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas.

Long-term survival depends primarily on the stage of the tumor at the time of diagnosis. In various studies, reported 5-year survival rates have ranged from 62% to 90% for stage IE lesions and from 29% to 50% for stage IIE lesions, but substantially lower rates are reported for stages III and IV lesions. Patients with low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas have a much better prognosis than patients with high-grade lymphomas; low-grade lymphomas are associated with 5-year survival rates of 75% to 91%, whereas high-grade MALT lymphomas are associated with 5-year survival rates of less than 60%.

After treatment, some patients may develop recurrent gastric lymphoma, whereas others are found to have recurrent tumor in distal nodal groups without evidence of gastric disease. Patients with recurrent lymphoma almost always become symptomatic within 2 years of treatment, so the prognosis is excellent for patients who remain asymptomatic for more than 5 years. Gastric lymphoma has a better prognosis than gastric carcinoma because of its inherent growth characteristics and its tendency to remain in the gastric wall for prolonged periods.

Radiographic Findings

Low-Grade Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma

Low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas may be manifested on double-contrast studies by variably sized, rounded, often confluent nodules involving a focal or, less frequently, diffuse segment of the stomach ( Fig. 33-20 ). Other MALT lymphomas may appear as small polypoid or ulcerated lesions, as shallow, irregular ulcers with nodular surrounding mucosa, or as focally distorted, enlarged rugal folds. These early lymphomas may be indistinguishable from early gastric cancer on the basis of the radiographic findings.

Endoscopic biopsy specimens should be obtained for a definitive diagnosis when low-grade MALT lymphomas are suspected on the basis of the radiographic findings. Although some patients may be found to have other conditions such as H . pylori gastritis without evidence of tumor (see later, “Differential Diagnosis”), it seems reasonable to accept a certain percentage of false-positive diagnoses because of the importance of detecting gastric MALT lymphomas at an early, curable stage.

Advanced Gastric Lymphoma

Advanced gastric lymphomas have an average diameter of 10 cm or more at the time of diagnosis. Although the entire stomach may be infiltrated by tumor, most cases involve the antrum and body. Depending on the gross pathologic features, gastric lymphomas may be classified radiographically as infiltrative, ulcerative, polypoid, or nodular lesions. There is considerable overlap between these types, however, with many lesions having combined radiographic features.

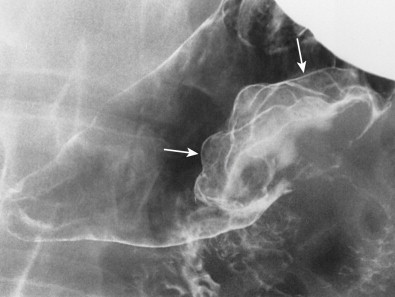

Infiltrative gastric lymphomas are characterized by focal or diffuse enlargement of rugal folds caused by submucosal spread of tumor ( Fig. 33-21A ). The folds can be massively enlarged and often have a distorted, nodular contour, so they can be mistaken for polypoid masses. Even with extensive lymphomatous infiltration, the stomach typically remains pliable and distensible because of the absence of associated fibrosis. However, some non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas may produce a linitis plastica appearance indistinguishable from that of a primary scirrhous carcinoma of the stomach. These lesions are characterized by varying degrees of narrowing of the gastric antrum, body, or fundus with nodularity, ulceration, and thickened or effaced mucosal folds ( Fig. 33-21B ). This linitis plastica appearance is caused by dense infiltrates of lymphomatous tissue in the gastric wall without associated fibrosis. The histopathologic findings are therefore similar to those of metastatic breast cancer in which gastric narrowing is caused by highly cellular deposits of metastatic tumor. Conversely, Hodgkin’s lymphoma involving the stomach produces a linitis plastica appearance by inciting a marked desmoplastic response similar to that of a primary scirrhous carcinoma.

Ulcerative lymphomas are characterized by one or more ulcerated lesions in the stomach ( Fig. 33-21C ). Occasionally, the ulcers may be surrounded by a smooth mound of tumor or symmetric radiating folds, mimicking the appearance of benign gastric ulcers. Usually, however, these ulcers have an irregular configuration associated with nodular surrounding mucosa or thickened, irregular folds resulting from lymphomatous infiltration of the gastric wall (see Fig. 33-21C ). Other gastric lymphomas may appear as giant cavitated lesions as a result of necrosis and excavation of the tumor.

Polypoid gastric lymphomas are characterized by one or more lobulated intraluminal masses indistinguishable from those of polypoid carcinomas ( Fig. 33-21D ). Finally, the nodular form of gastric lymphoma is characterized by multiple submucosal nodules or masses, ranging from several millimeters to several centimeters in size. These submucosal masses often ulcerate, producing typical bull’s-eye or target lesions ( Fig. 33-21E ). In such cases, the central barium collections tend to be relatively large in relation to the surrounding elevations. Other patients may have multiple polyps indistinguishable from those associated with the various polyposis syndromes.

About 10% of patients with gastric lymphoma have contiguous transcardiac spread of tumor from the gastric fundus into the distal esophagus. Esophageal involvement is usually manifested by thickened, irregular folds, luminal narrowing or, less frequently, a polypoid mass in the distal esophagus. Because adenocarcinoma is a much more common malignant tumor in the stomach, these findings are more likely to result from distal esophageal involvement by a fundal or cardiac carcinoma.

Gastric lymphoma may also extend into the duodenum by contiguous transpyloric spread. In various series, 30% to 40% of patients with gastric lymphoma have associated duodenal involvement on barium studies (see later, “Duodenal Lymphoma”). Because gastric carcinoma invades the duodenum in only 5% to 25% of patients, it has been suggested that concomitant involvement of the stomach and duodenum by tumor should favor a diagnosis of lymphoma. However, adenocarcinoma is so much more common than lymphoma that it is still the most likely diagnosis on empirical grounds.

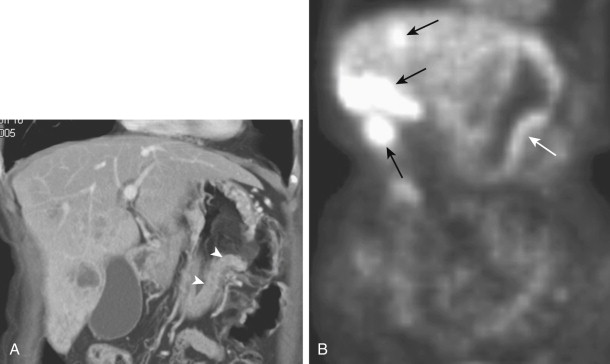

Patients with advanced gastric lymphoma are sometimes treated exclusively with radiation or chemotherapy. Follow-up barium studies or CT scans are useful in these patients for documenting the response to treatment and for evaluating GI bleeding or other symptoms that develop after the initiation of radiation or chemotherapy ( Figs. 33-22 and 33-23 ). Follow-up studies may show dramatic regression or resolution of the lymphomatous lesions, often associated with narrowing and deformity of the stomach at the site of the previous lesion as a result of residual scarring and fibrosis. In other patients, chemotherapy may lead to marked regression of ulcerated mass lesions with the development of benign-appearing ulcers or ulcer scars at the site of the previous lesions (see Fig. 33-22C ). Chemotherapy may also lead to further ulceration, a confined perforation or, rarely, free perforation of these lymphomatous lesions with the development of massive upper GI bleeding or peritonitis (see Figs. 33-22B and 33-23B ).