Ovarian neoplasms are histologically diverse, with approximately 15 types among malignant tumors alone. Benign ovarian masses include benign neoplasms and other predominantly cystic or hemorrhagic lesions most commonly arising from ovulatory function. Ovarian cancer is more common in women aged 45 and older, and is the second most common gynecologic malignancy, after endometrial cancer. It is the fifth leading cause of cancer death of women in the United States. Unfortunately most malignant ovarian tumors are diagnosed in an advanced stage, after regional spread or metastasis, and carry an overall poor 5-year survival rate.

Fallopian tube cancer is a rare malignancy, with approximately 1500 cases reported in the literature since the first case report in 1847. Once metastatic, it demonstrates a similar course as ovarian cancer, although some sources suggest it carries an overall worse prognosis, stage for stage.

Disease

Definition: Ovarian Cancer

Ovarian cancer arises most commonly from the epithelial cells or the germ cells of the ovary. A third less common variety includes malignancies of the sex cord-stromal tissue.

Definition: Fallopian Tube Carcinoma

The pathologic diagnosis for fallopian tube cancer is more complex and based on the following criteria: The tumor must arise from the endosalpinx, demonstrate cellular histology consistent with tubal epithelium, and have demonstrable transition from malignant to benign epithelium. The tumor in the salpinx also must be larger than any tumor found on the ovary or in the endometrium.

Prevalence and Epidemiology: Ovarian Cancer

Ovarian cancer is the second most common gynecologic cancer in the United States and one of the most deadly: It is the fifth leading cause of cancer death in American women. Ovarian cancer will cause approximately 13,800 deaths per year in 2010. Since 2002, death rates from ovarian cancer have been decreasing about 1.4% per year.

The overall 5-year survival rate of ovarian cancer is reported at 46%. Likelihood of survival depends on the stage of cancer at diagnosis, with localized disease demonstrating a 94% 5-year survival rate. On the other hand, diagnosis with distant metastases is associated with a 5-year survival rate of 28%. Those with regional disease have intermediate 5-year survival of 73%.

Prevalence and Epidemiology: Fallopian Tube Carcinoma

Fallopian tube cancer comprises only 0.1% to 1.8% of gynecologic cancers. Fallopian tube cancer is mostly diagnosed in postmenopausal women, sometimes incidentally, and is also often widespread at the time of diagnosis. Overall survival is better than for ovarian carcinoma. If the disease is resected while still confined to the tube, 5-year survival rate is approximately 90%. Once the tumor extends to the surface of the tube and beyond, however, it carries a poor 5-year survival rate.

Etiology and Pathophysiology: Ovarian Cancer

Ovarian cancers originate from all three histologic types of ovarian tissue: the surface epithelium, the germ cells, or the ovarian stroma. Ninety percent of cancers arise from the surface epithelium, and research suggests that most of these derive from the pluripotent coelomic epithelium, which gives rise embryologically to the müllerian ducts. These cells give rise to the tubal, endometrial, and cervical tissues of the female genital tract, and some are also incorporated into the ovarian cortex. Therefore the subtypes of epithelial ovarian tumors reflect their embryologic origin, including serous (tubal), mucinous (cervical), and endometrioid (endometrial), along with the less common clear cell, transitional cell (Brenner tumor), and epithelial stromal varieties. Each of these tumor types can exist as benign, borderline, or malignant neoplasms, which is determined pathologically. Serous carcinomas, which comprise 40% of all ovarian malignancies, are the most common malignant ovarian tumor.

Germ cell tumors include teratomas, which can be benign or malignant, dysgerminomas, endodermal sinus (yolk sac) tumors, choriocarcinomas, embryonal carcinomas, and mixed germ cell tumors. Stromal tumors include granulosa-thecal cell tumors, fibromas, thecomas, and fibrothecomas, as well as Sertoli–Leydig cell tumors (androblastomas). Other less common subtypes are beyond the scope of this discussion.

The single most significant risk factor for developing ovarian cancer is a family history of the disease. Genetic factors can greatly increase risk for developing ovarian cancer, but the majority of cases have no genetic basis. Those with a genetic risk include BRCA-1 and BRCA-2 carriers, Lynch II syndrome (hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer), and site-specific ovarian cancer syndrome. For example, 20% to 40% of BRCA mutation carriers will develop ovarian cancer. Familial or individual history of breast, colon, or endometrial cancers increases risk. Risk for developing ovarian cancer is also related to lifetime ovulatory frequency; therefore ovarian cancer risk is increased in women who delay childbearing, are nulliparous, or undergo early menarche or delayed menopause. Some of these factors may influence increased incidence in developed countries; however, ovulatory suppression through use of oral contraceptives decreases risk. Lastly, there is an established risk associated with endometriosis and development of endometrioid or clear cell ovarian tumors. Sometimes the tumor arises from endometriosis of the ovary, and other times endometriosis is identified separate from the tumor itself, more often in association with the endometrioid or clear cell subtype than expected based on frequency of these tumors in the general population.

Etiology and Pathophysiology: Fallopian Tube Carcinoma

Histologic types of fallopian tube cancer are similar to ovarian cancer. The most prevalent type by far is papillary serous adenocarcinoma, comprising 90% of recent cases of fallopian tube cancer. The next most common type is endometroid carcinoma, followed by scattered cases of transitional cell, clear cell, undifferentiated, or mixed types. Research into etiology of fallopian tube cancer is hindered by the rarity of disease. Similar to ovarian cancer, nulliparity is probably a significant risk factor. BRCA mutations probably increase the risk for developing fallopian tube cancer, as carcinoma in situ has been detected in specimens of BRCA patients who underwent prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomies.

Manifestations of Disease

Clinical Presentation: Ovarian Cancer

Historically ovarian cancer has been a late-presenting and deadly disease, the so-called “silent killer.” Some recent research into the clinical presentation suggests that certain signs and symptoms can be present early in the disease, including specifically abdominal pain, distended and hard abdomen, abdominal mass, and abnormal vaginal bleeding. This symptom–sign complex was found to have greater than 70% sensitivity and specificity in a series of 432 patients. Nevertheless, signs and symptoms of ovarian cancer are frequently nonspecific and may be associated with many other disease states, which can result in misdiagnosis and delay; however, the presence and recognition of these multiple clinical features might allow a woman with early ovarian cancer and her caregiver to seek and achieve a diagnosis before there is a chance for spread of disease.

Clinical Presentation: Fallopian Tube Carcinoma

The entity of hydrops tubae profluens consisting of colicky abdominal pain, relief by passage of a watery or serosanguineous discharge, and a palpable pelvic mass comprise a classical triad of clinically presenting fallopian tube cancer. Only 10% of patients present in this fashion, however, and abnormal vaginal bleeding is the overall most common symptom, observed in approximately 50% of patients. More than half of the patients diagnosed with fallopian tube cancer have stage I or II disease with relatively early detection attributed to clinical presentation.

Imaging Indications and Algorithm

Lesion Discovery and Approach

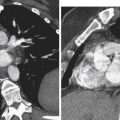

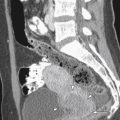

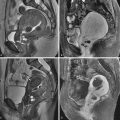

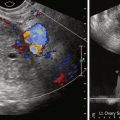

Imaging choice in the evaluation of adnexal masses varies based on the questions being asked, as well as the situation in which the patient presents. Usually a pelvic ultrasound (US) is the initial examination chosen if a mass is suspected clinically. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be helpful to “problem solve,” most frequently to secure a suspected benign diagnosis. Computed tomography (CT) is used primarily in the staging of malignancies. Occasionally and with increasing frequency CT is used as a screening modality for abdominal pain or other nonspecific complaints and results in initial diagnosis of a pelvic mass or suspected metastatic ovarian carcinoma. In cases of a nonspecific pelvic mass detected on such a CT, without evidence of malignancy such as ascites or metastatic disease, immediate and/or interval sonography can be complementary, helping to confirm or determine anatomic relationships and determine presence of persistent lesions in follow-up evaluations. The goal of pelvic imaging is focused on determining whether the adnexal mass has benign or malignant features, rather than attempting to determine specific histologic type.

Cancer Screening

Screening for ovarian cancer can include pelvic sonography and serum cancer antigen (CA)-125 testing. Either test can be implemented alone, or both can be used. The goal of screening is mortality reduction by detection of cancer at an earlier stage with more curable disease. There is no solid evidence to date that this is possible, despite multiple screening trials. Sonographic screening leads to exploratory surgery when there is a persistent mass or enlarged ovary, for age, or for cystic lesion with internal soft tissue nodules. Screening in this manner is controversial and complicated because there are many limitations to both sonographic pelvic surveillance and CA-125. For example, low disease prevalence in the general population (1.3%) reduces utility of screening. A large number of benign and physiologic lesions also end up being explored unnecessarily. There is also concern that the most aggressive cancers can develop to advanced stage between screening studies. Therefore screening is considered more suitable for subjects with hereditary cancer risk such as Lynch II (10% lifetime risk for ovarian cancer) or BRCA mutations. No screening is advised for fallopian tube cancer.

Staging of Ovarian and Fallopian Tube Cancers

Staging of ovarian cancer is surgical, involving a complete laparotomy, with hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy, omentectomy, biopsies and/or removal of pelvic and retroperitoneal lymph nodes and any gross peritoneal disease, plus cytologic evaluation of washings ( Table 34-1 ). Both the TNM and International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging terminology may be reported. Staging for fallopian tube cancer is nearly identical to ovarian cancer staging; except for early-stage disease (T1 through T1b), the tumor is limited to the fallopian tubes rather than ovary ( Table 34-2 ). Presurgical imaging will most often involve a clinical staging survey for metastatic disease. MRI and CT have been determined to have similar accuracy, superior to US, for this purpose because these modalities are particularly more accurate for determination of intraperitoneal metastases and lymphadenopathy. In clinical practice, CT is used most commonly, owing mainly to lower cost and ease of use. Some patients with metastatic disease to solid organs, stage IV, confirmed through biopsy, will not undergo complete surgical staging.

| Primary Tumor (T) | ||

|---|---|---|

| TNM Categories | FIGO Stages | |

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed | |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor | |

| T1 | I | Tumor limited to ovaries (one or both) |

| T1a | IA | Tumor limited to one ovary; capsule intact, no tumor on ovarian surface; no malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings |

| T1b | IB | Tumor limited to both ovaries; capsules intact, no tumor on ovarian surface; no malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings |

| T1c | IC | Tumor limited to one or both ovaries with any of the following: capsule ruptured, tumor on ovarian surface, malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings |

| T2 | II | Tumor involves one or both ovaries with pelvic extension |

| T2a | IIA | Extension and/or implants on uterus and/or tube(s); no malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings |

| T2b | IIB | Extension to and/or implants on other pelvis tissues; no malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings |

| T2c | IIC | Pelvic extension and/or implants (T2a or T2b) with malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings |

| T3 | III | Tumor involves one or both ovaries with microscopically confirmed peritoneal metastasis outside the pelvis |

| T3a | IIIA | Microscopic peritoneal metastasis beyond pelvis (no macroscopic tumor) |

| T3b | IIIB | Macroscopic peritoneal metastasis beyond pelvis ≤2 cm in greatest dimension |

| T3c | IIIC | Peritoneal metastasis beyond pelvis >2 cm in greatest dimension and/or regional lymph node metastasis |

| Regional Lymph Nodes (N) | ||

| TNM Categories | FIGO Stages | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed | |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis | |

| N1 | IIIC | Regional lymph node metastasis |

| Distant Metastasis (M) | ||

| TNM Categories | FIGO Stages | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis | |

| M1 | IV | Distant metastasis (excludes peritoneal metastasis) |

| Primary Tumor (T) | ||

|---|---|---|

| TNM Categories | FIGO Stages | |

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed | |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor | |

| Tis * | Carcinoma in situ (limited to tubal mucosa) | |

| T1 | I | Tumor limited to the fallopian tube(s) |

| T1a | IA | Tumor limited to one tube, without penetrating the serosal surface; no ascites |

| T1b | IB | Tumor limited to both tubes, without penetrating the serosal surface; no ascites |

| T1c | IC | Tumor limited to one or both tubes with extension onto or through the tubal serosa, or with malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings |

| T2 | II | Tumor involves one or both fallopian tubes with pelvic extension |

| T2a | IIA | Extension and/or metastasis to the uterus and/or ovaries |

| T2b | IIB | Extension to other pelvic structures |

| T2c | IIC | Pelvic extension with malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings |

| T3 | III | Tumor involves one or both fallopian tubes, with peritoneal implants outside the pelvis |

| T3a | IIIA | Microscopic peritoneal metastasis outside the pelvis |

| T3b | IIIB | Macroscopic peritoneal metastasis outside the pelvis ≤2 cm in greatest dimension |

| T3c | IIIC | Peritoneal metastasis outside the pelvis and >2 cm in diameter |

| Regional Lymph Nodes (N) | ||

| TNM Categories | FIGO Stages | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed | |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis | |

| N1 | IIIC | Regional lymph node metastasis |

| Distant Metastasis (M) | ||

| TNM Categories | FIGO Stages | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis | |

| M1 | IV | Distant metastasis (excludes metastasis within the peritoneal cavity) |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree