Spondylitis or infection of the spine is a spectrum of diseases involving the bone, disks, and/or ligaments. Because of a significant increase in the immunocompromised patient population, spinal infections are a growing and changing group of conditions, making the diagnosis based on imaging more challenging. Most cases of spinal infections are pyogenic and occur after hematogeneous spread of an infection located elsewhere in the body. A prompt diagnosis remains crucial and MR imaging remains the cornerstone in the diagnosis. This article provides a pictorial overview of the complications and sequelae in spinal infections in general. Discussed are postoperative infections, extraspinal spread of infection, fractures and malformations, and neurologic complications.

Key points

- •

Worldwide most complications of spondylitis are still seen in cases of tuberculous spondylitis.

- •

However, in Western countries more and more complications are seen in postoperative spondylitis.

- •

The number of immunosuppressed patients is rising. They are more susceptible to infections in general and spinal infections in particular.

- •

Clinicians need to be aware of the possible slow progressive course with relatively little and nonspecific symptoms of spinal infectious disease.

- •

Early diagnosis depends mainly on biochemical and imaging findings. With the advent of MR imaging patients are diagnosed earlier and hence can be treated conservatively.

- •

Progressive disease with spinal instability is generally treated as spinal trauma.

Introduction

Spondylitis, or infection of the spine (from Ancient Greek σπóνδυλoς [spóndulos] = spine), is a spectrum of diseases involving the bone, disks, and/or ligaments. Therefore, in this spectrum we include spondylitis (also infection of the vertebral body), discitis, spondylodiscitis, vertebral osteomyelitis, pyogenic facet arthritis, epidural infections, meningitis, polyradiculitis, and myelitis.

This article mainly discusses discitis, spondylitis, and spondylodiscitis, primarily because these occur most frequently. Osteomyelitis of the posterior elements is rare and should raise suspicion of tuberculosis or an iatrogenic cause.

Mostly spondylitis and discitis are caused by hematogenous spread of an infection located elsewhere in the body. Only rarely is it nonhematogenous and in these cases it is mostly iatrogenic, caused by interventional procedures, surgical intervention, penetrating trauma, contiguous infection, or direct inoculation.

In ancient history the most common cause of spinal infection was Mycobacterium tuberculosis . In most Western countries this is not endemic. However, the incidence of tuberculosis is rising, especially in immunocompromised patients. The most frequent cause in western countries is the pyogenic form of spondylodiscitis, most commonly by Staphylococcus aureus infection (60%).

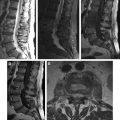

Spinal infections are most frequently located at the lumbar level (60%), less frequently at the thoracic level (30%), and only in 10% at the cervical level. Only rarely is it located in the sacrum.

There is a difference in spondylitis in children versus adults. Until the age of 15 years, children have numerous paravertebral and intraosseous collateral arteries and a direct blood supply to the intervertebral disks, reaching the nucleus pulposus, and thus the infection is primarily discogenic. The course of discitis in children is often benign and is treated with antibiotics. Surgical abscesses are rare and drainage or decompression is hardly ever needed. This blood supply regresses in adults and predominantly the end-artery metaphyseal branches remain. The infection usually begins in the anterior subchondral regions and spreads secondarily to the disk.

MR imaging is the modality of choice in the evaluation and diagnosis of spinal infections in an early stage. It is often not helpful for routine follow-up of the disease because it does not correlate with the clinical course. It sometimes shows disease progression despite treatment.

Computed tomography is sensitive for delineating bone and evaluating bone destruction, but also allows imaging a larger field of view, which can be useful in case of extensive extravertebral expansion, such as in the abdomen, chest, or mediastinum.

Radiographs usually remain normal 2 to 8 weeks after the onset of infection but are still useful for the evaluation of spinal alignment. Therefore, plain radiographs often serve as a baseline investigation for further follow-up.

Bone scintigraphy shows arterial hyperemia and a progressive focal uptake and is therefore highly sensitive. Tuberculosis infections, however, are cold in 35% to 40% of cases.

On PET scan spinal infections are usually fluorodeoxyglucose avid. Therefore, nuclear medicine is used in the work-up of spondylodiscitis in combination with MR imaging. Spinal infections can be an incidental finding on nuclear imaging studies, necessitating further work-up.

Mortality rates vary between 2% and 11% and are remarkably better than before the use of effective antibiotics pre–World War II, with a mortality rate of about 70%. The most common complication of spondylitis is abscess formation in the psoas muscle. Epidural abscesses and compression fractures are not uncommon. Mechanical compression, however, is the most common cause of functional compromise of the spinal cord. Ischemic compromise of the spinal cord is infrequent. Extensive destruction of the vertebral spine is frequently seen in endemic areas of M tuberculosis and commonly is not encountered in the Western world.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree