The most common indication for parathyroid imaging is hyperparathyroidism, which is caused by a solitary parathyroid adenoma in most patients. The primary function of parathyroid imaging is localization of the abnormal parathyroid gland, enabling the surgeon to pursue a minimally invasive resection. Ultrasound and 99m Tc sestamibi scintigraphy are the mainstays for the preoperative localization of culprit lesions. The emerging modality of SPECT-CT can improve the sensitivity of 99m Tc sestamibi scintigraphy and its use is encouraged when available. CT and MR imaging are useful as adjuncts, particularly as anatomic correlates to suspected ectopic glands on 99m Tc sestamibi scintigraphy that are inaccessible to ultrasound. In cases of suspected parathyroid carcinoma, preoperative CT or MR imaging is recommended for surgical planning.

Embryology and anatomy

The parathyroid glands develop at 6 weeks of fetal life and migrate caudally at 8 weeks. The paired superior parathyroid glands derive, along with the thyroid gland, from the dorsal portions of the fourth branchial pouch. The superior parathyroid glands tend to be consistent in position, posterior and lateral to the upper pole of the thyroid, at the level of the cricoid cartilage, along the inferior thyroid artery and recurrent laryngeal nerve. The inferior parathyroid glands, along with the thymus, develop from the third branchial pouch and migrate caudally to rest inferior to the relatively less mobile superior parathyroid glands. Occasionally the inferior parathyroid glands migrate to the level of the aortic arch, or in rare circumstances, fail to migrate and remain in the high neck.

The parathyroid glands are usually located between the posterior border of the thyroid gland and its fibrous capsule, although they can be intrathyroidal also. A normal parathyroid gland has dimensions of 5 × 3 × 1 mm and weight of 30 to 40 mg. Although most patients have four parathyroid glands, approximately 5% have fewer, and 3% to 13% have supernumerary glands.

Pathology

Hyperparathyroidism

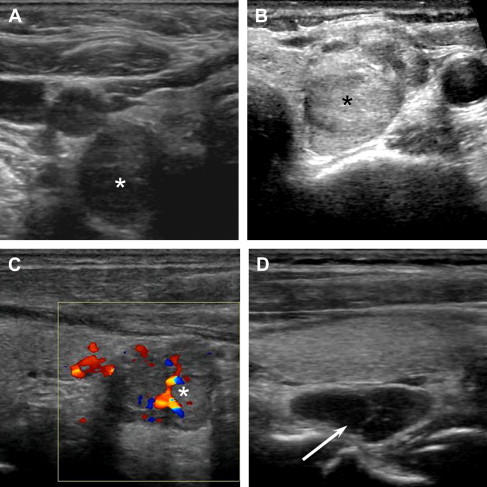

Hyperparathyroidism can be primary, secondary, or tertiary. Primary hyperparathyroidism, defined as an independent focus of parathyroid hormone overproduction, has an estimated prevalence of 1:7000 in the United States. Women are affected approximately twice to three times as often as men. Diagnosis is based on elevated calcium and parathyroid hormone levels and clinical symptoms consist of renal calculi, gastric ulcers, bone cysts, and mental depression. In the vast majority of patients (approximately 85%), a single parathyroid adenoma is the cause of disease ( Fig. 1 ); the remaining causes include diffuse hyperplasia (10%), multiple adenomas (4%), or rarely parathyroid carcinoma or cysts.

Secondary hyperparathyroidism occurs because of hyperplasia of the parathyroid glands following long-term hyperstimulation and parathyroid hormone release. In contrast to primary hyperparathyroidism, elevated parathyroid hormone levels do not result in hypercalcemia. Classically this has been ascribed to most patients who have secondary hyperparathyroidism suffering from chronic renal failure and therefore having an underlying hypocalcemic state, although this has not been fully elucidated. Rarer causes of secondary hyperparathyroidism include diminished calcitriol levels, resistance to parathyroid hormone by skeletal tissue, rickets, and malabsorption syndromes.

Following long-term hyperstimulation, the parathyroid glands start to function autonomously and produce high levels of parathyroid hormone, despite correction of underlying chronic hypocalcemia. Tertiary hyperparathyroidism refers to the subsequent hypercalcemia produced by this autonomous parathyroid function.

Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia

Multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) is a hereditary syndrome characterized by abnormal function of two or more endocrine organs. MEN1 is characterized by primary hyperparathyroidism, pancreatic endocrine tumors, and anterior pituitary gland neoplasms, whereas MEN2A is characterized by pheochromocytomas, medullary thyroid carcinoma, and hyperparathyroidism. In both cases the hyperparathyroidism is multiglandular; however, in MEN1 it is characterized by an asynchronous and steadily progressive course, whereas in MEN2A it has a later onset and less severe effects at clinical evaluation, with lower morbidity.

Parathyroid Cysts

There are two types of parathyroid cysts. The first is a purely cystic parathyroid lesion, attributable to embryologic remnants of the third or fourth branchial pouches or enlargement of microcysts within the parathyroid because of colloid retention ( Fig. 2 ). The second type refers to cystic necrosis or degeneration of parathyroid adenomas. Both entities can cause hypercalcemia because of high parathyroid hormone level in the cyst fluid.

Parathyroid Carcinoma

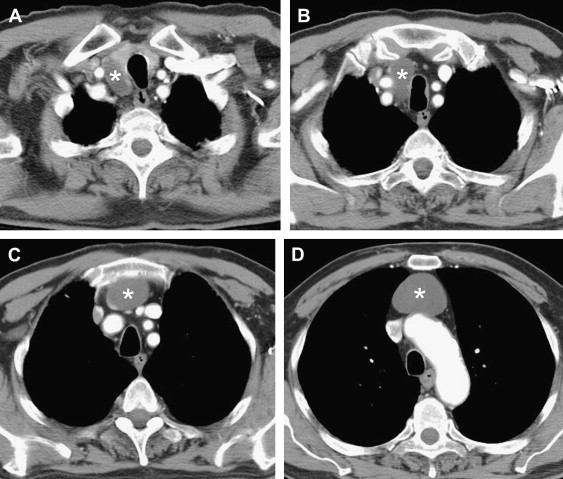

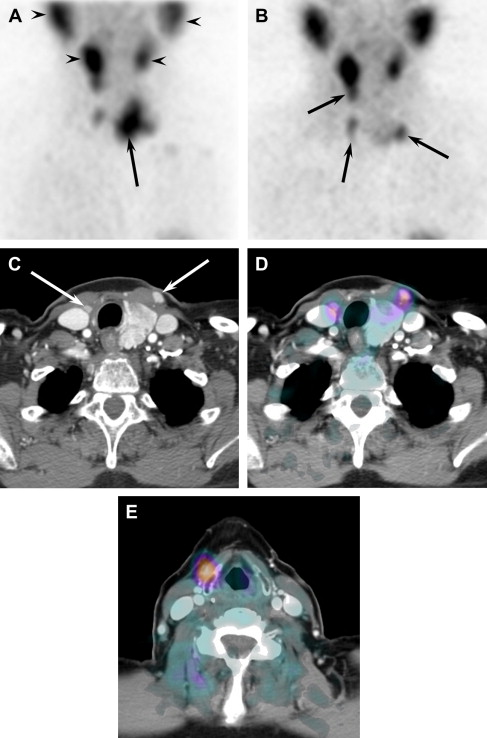

Carcinoma occurs in 0.5% to 1.0% of patients who have primary hyperparathyroidism. It is usually indistinguishable from benign adenoma on clinical evaluation and imaging ( Fig. 3 ). It can be suggested by a palpable neck mass on examination or demonstration of invasion of adjacent structures on imaging, however. Classically, parathyroid carcinomas are said to be slow growing with distant metastasis occurring late in the course of the disease.

Parathyromatosis

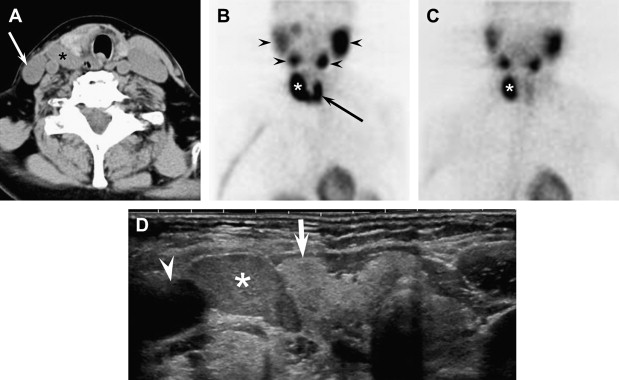

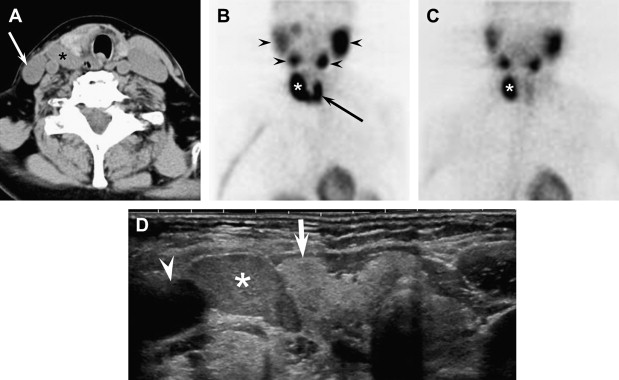

Parathyromatosis is a rare condition characterized by findings of multiple rests of hyperfunctioning parathyroid tissue in the neck and mediastinum with resultant persistent or recurrent hyperparathyroidism ( Fig. 4 ). It has been associated with MEN1, spillage of hypercellular parathyroid tissue during surgical exploration of the neck, or hyperfunctioning parathyroid rests left behind during ontogenesis. Importantly, ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration does not seem to predispose patients to development of parathyromatosis.

Pathology

Hyperparathyroidism

Hyperparathyroidism can be primary, secondary, or tertiary. Primary hyperparathyroidism, defined as an independent focus of parathyroid hormone overproduction, has an estimated prevalence of 1:7000 in the United States. Women are affected approximately twice to three times as often as men. Diagnosis is based on elevated calcium and parathyroid hormone levels and clinical symptoms consist of renal calculi, gastric ulcers, bone cysts, and mental depression. In the vast majority of patients (approximately 85%), a single parathyroid adenoma is the cause of disease ( Fig. 1 ); the remaining causes include diffuse hyperplasia (10%), multiple adenomas (4%), or rarely parathyroid carcinoma or cysts.

Secondary hyperparathyroidism occurs because of hyperplasia of the parathyroid glands following long-term hyperstimulation and parathyroid hormone release. In contrast to primary hyperparathyroidism, elevated parathyroid hormone levels do not result in hypercalcemia. Classically this has been ascribed to most patients who have secondary hyperparathyroidism suffering from chronic renal failure and therefore having an underlying hypocalcemic state, although this has not been fully elucidated. Rarer causes of secondary hyperparathyroidism include diminished calcitriol levels, resistance to parathyroid hormone by skeletal tissue, rickets, and malabsorption syndromes.

Following long-term hyperstimulation, the parathyroid glands start to function autonomously and produce high levels of parathyroid hormone, despite correction of underlying chronic hypocalcemia. Tertiary hyperparathyroidism refers to the subsequent hypercalcemia produced by this autonomous parathyroid function.

Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia

Multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN) is a hereditary syndrome characterized by abnormal function of two or more endocrine organs. MEN1 is characterized by primary hyperparathyroidism, pancreatic endocrine tumors, and anterior pituitary gland neoplasms, whereas MEN2A is characterized by pheochromocytomas, medullary thyroid carcinoma, and hyperparathyroidism. In both cases the hyperparathyroidism is multiglandular; however, in MEN1 it is characterized by an asynchronous and steadily progressive course, whereas in MEN2A it has a later onset and less severe effects at clinical evaluation, with lower morbidity.

Parathyroid Cysts

There are two types of parathyroid cysts. The first is a purely cystic parathyroid lesion, attributable to embryologic remnants of the third or fourth branchial pouches or enlargement of microcysts within the parathyroid because of colloid retention ( Fig. 2 ). The second type refers to cystic necrosis or degeneration of parathyroid adenomas. Both entities can cause hypercalcemia because of high parathyroid hormone level in the cyst fluid.

Parathyroid Carcinoma

Carcinoma occurs in 0.5% to 1.0% of patients who have primary hyperparathyroidism. It is usually indistinguishable from benign adenoma on clinical evaluation and imaging ( Fig. 3 ). It can be suggested by a palpable neck mass on examination or demonstration of invasion of adjacent structures on imaging, however. Classically, parathyroid carcinomas are said to be slow growing with distant metastasis occurring late in the course of the disease.

Parathyromatosis

Parathyromatosis is a rare condition characterized by findings of multiple rests of hyperfunctioning parathyroid tissue in the neck and mediastinum with resultant persistent or recurrent hyperparathyroidism ( Fig. 4 ). It has been associated with MEN1, spillage of hypercellular parathyroid tissue during surgical exploration of the neck, or hyperfunctioning parathyroid rests left behind during ontogenesis. Importantly, ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration does not seem to predispose patients to development of parathyromatosis.

Parathyroid imaging

Several modalities can be used to image the parathyroid gland. Because hyperparathyroidism caused by a solitary parathyroid adenoma is by far the most common form of parathyroid pathology, imaging is often geared toward accurate preoperative identification of the offending adenoma. Accurate preoperative identification of a parathyroid adenoma allows for directed parathyroid surgery, which is as effective as traditional bilateral neck exploration, but is associated with reduced surgical time, reduced hospital stay, improved cosmetic result, use of local rather than general anesthesia, and no risk for permanent hypoparathyroidism. This identification can be accomplished with neck ultrasound, 99m Tc sestamibi scintigraphy, or, ideally, a combination of both. CT and MR imaging are primarily used to further evaluate suspected cases of parathyroid carcinoma and parathyroid cysts, although they can also be used to aid in diagnosis in select cases of hyperparathyroidism.

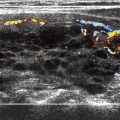

Ultrasound

Technique

Imaging should be performed with 10-MHz or higher linear array transducers to provide optimal gray-scale and color Doppler imaging. The patient is examined in the supine position with the neck slightly extended, identical to the position used to scan the thyroid gland. Rotation of the neck away from the side being examined and asking the patient to swallow may aide in locating enlarged parathyroid glands. Scanning is performed in the transverse and longitudinal planes with attention focused posterior and inferior to the thyroid gland, medial to the carotid artery and jugular vein, and along the tracheoesophageal groove. If necessary the transducer can be angled to increase visualization inferiorly along the trachea and into the superior mediastinum or behind the clavicle. Graded compression may also aid in differentiating a relatively incompressible gland from surrounding soft tissue. Color Doppler sonography should be performed on all suspected adenomas because vascularity is important to the sonographic diagnosis ( Fig. 5 ).