PAROTID TUMORS AND TUMORLIKE CONDITIONS

KEY POINTS

- Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are instrumental in determining the intrinsic versus extrinsic origin of a parotid-region mass.

- Such imaging may provide critical information concerning the extent of a primary parotid tumor.

- Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging can often help to determine the relationship of an intrinsic parotid mass to the facial nerve.

- Perineural spread of parotid cancer is a critical factor in treatment strategy, and imaging helps to evaluate this important risk factor.

- When a parotid-region mass is due to metastases to parotid nodes, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging can help to identify parotid cancer or another etiology as a cause.

- Slowly progressive peripheral facial nerve palsy may be due to parotid cancer, and imaging should be employed whenever this occurs clinically.

- Computed tomography and especially magnetic resonance imaging are useful for surveillance imaging following treatment for parotid tumors while fluorine-18 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) has significant limitations in this regard.

INTRODUCTION

A Dilemma: Parotid-Region Mass of Parotid or Nonparotid Origin

Mass lesions in the parotid region will be intrinsic to the gland in about 75% to 80% of patients. In the remainder, such masses will be due to periparotid adenopathy (Fig. 179.1 and Chapter 175) or masses arising from the mandible and/or temporomandibular joint (TMJ) (Chapter 103) and masticator space (Chapter 145), parapharyngeal space (Chapters 143–144) or temporal bone, and rarely the facial nerve (Fig. 179.2). Infiltrating systemic disease such as sarcoidosis, manifestations of autoimmune sialoadenitis and lymphoma (Chapter 178) can mimic a parotid epithelial-origin tumor if those conditions are not otherwise known to be present. Diagnostic imaging has a major impact on sorting out these possibilities and thereby significantly alters medical decision making in a high percentage of patients. The contributions are equally important in many cases of intrinsic glandular epithelial-origin neoplasms.

Parotid Gland Tumors

Major salivary glands contain several different groups of functioning and support cells. This leads to the variety of possible histologic neoplastic diagnoses discussed in Chapter 22. Precise histologic diagnosis by frozen section and needle biopsy may be difficult, especially with regard to distinguishing between benign and malignant neoplasms. Those planning care must be very aware of this limitation. Imaging features can sometimes help to anticipate malignancies, although the appearance may be misleading where masses appearing to have benign features on imaging end up being confirmed as malignant tumors. Because of this dilemma, both benign and malignant tumors are discussed in this chapter along with some of their more common potential mimics.

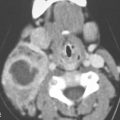

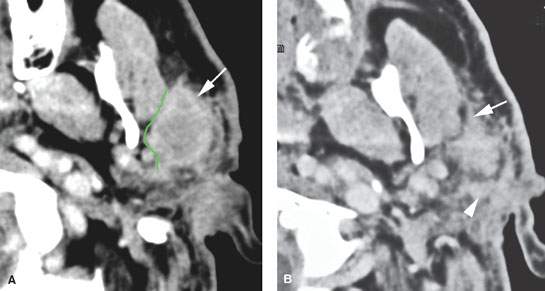

FIGURE 179.1. Seven patients with parotid-region masses of nonparotid origin. A: Patient 1. Computed tomography (CT) study of a patient who had two unsuccessful attempts to determine the histology of the parotid-region mass: one an open procedure and one a needle biopsy. No prior imaging was done. However, following imaging, the source of the mass was identified as osteochondroma of the mandible. B: Patient 2. CT scan showing the parotid-region mass to be a lipoma. C: Patient 3 is a 19 year old presenting with a parotid-region mass. The patient was initially treated by a parotid surgical approach for a mass that was eventually proven to be synovial cell sarcoma of the masticator space. Its true origin was not interpreted correctly on the initial diagnostic imaging study. The following three patients are examples of adenopathy mimicking a parotid-origin neoplasm. D: Patient 4. Ultrasound of a parotid mass in a 10 year old with morphology typical of an intraparotid lymph node. This was a reactive lymph node that resolved without therapy. Further imaging was not necessary. E: Patient 5. Contrast-enhanced CT study of a parotid tail–region mass eventually shown to be a solitary lymph node that was metastatic from a previously treated skin cancer. F–H: Patient 6. A patient who previously was treated for skin cancer. Contrast-enhanced CT was done. In (F), there is a parotid tail metastatic lymph node (arrow). In (G), there is a node in the deeper portion of the parotid tail (arrow) medial to the external carotid artery and retromandibular vein. In (H), there are multiple intraparotid metastatic lymph nodes. I–M: Patient 7 also with a history of previously treated skin cancer. The patient presented with lymph nodes at the parotid tail, but the figures included show extensive adenopathy in the external jugular nodes (arrows in L). There are also abnormal nodes due to backup adenopathy at level 1 and metastatic adenopathy in level 5 and extending to the low neck. (NOTE: This pattern of adenopathy, when recognized in a parotid-region mass, should point to a primary skin cancer as a likely etiology even though the patient may not recall having been treated for such a cancer.)

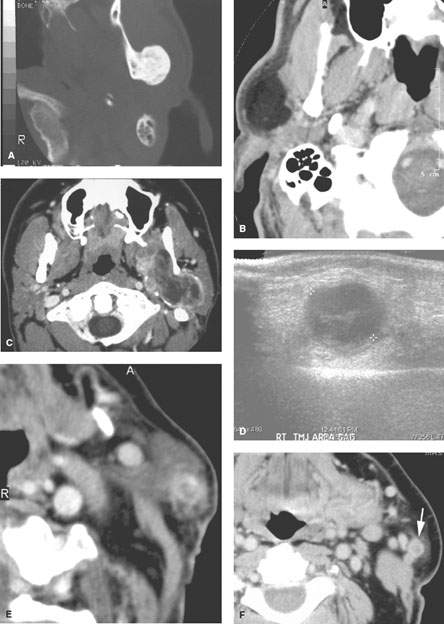

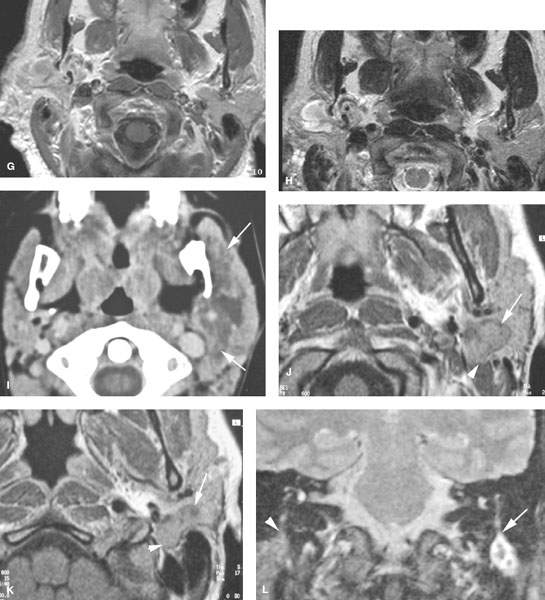

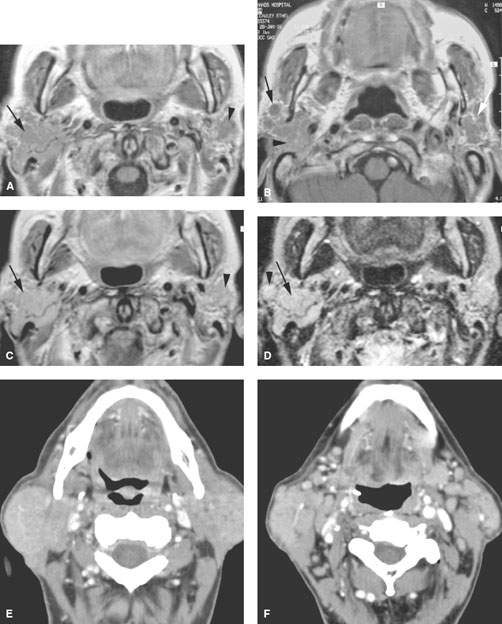

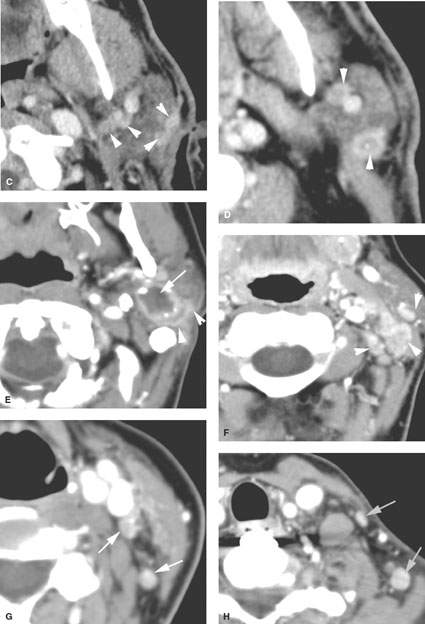

FIGURE 179.2. Four patients with parotid-region masses due to tumors of facial nerve origin. A–F: Patient 1. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) study. In (A), there is a mass overlying the masseter muscle, which in (B) is seen to be spreading along the facial nerve (arrows). Magnetic resonance (MR) in (C) through (E) shows the lesion spreading along the facial nerve (arrows) as far proximally as the cistern of the trigeminal ganglion (arrowheads in E). Perineural tumor extends from the cistern of the trigeminal ganglion to the main trunk of the facial nerve (arrow in E). In (F), a CT study shows anterior-grade spread of tumor along one of the buccal branches of the facial nerve. G, H: Patient 2. MR of T1-weighted (T1W) and T2-weighted (T2W) images, respectively, showing a plexiform neurofibroma of the facial nerve presenting as a parotid mass. This was the only manifestation of neurofibromatosis in this patient. I: Patient 3. Contrast-enhanced CT study showing a plexiform neurofibromatosis presenting as a parotid-region mass. This was the first indication of neurofibromatosis in this patient. J–L: Patient 4. MR study in a patient presenting with a parotid-region mass. Facial nerve function was intact. T1W images in (J) and (K) show a well-circumscribed mass along the expected course of the main trunk of the facial nerve (arrow) extending just inferomedial to the posterior belly of the digastric muscle (arrowheads) and spreading more distally along the main trunk of the facial nerve into the substance of the parotid gland (arrows). In (L), the T2W image shows the mass with morphology typical of schwannoma coming to the stylomastoid foramen but not up the descending facial canal (arrow) compared to the normal anatomy in this region on the opposite side.

ANATOMIC AND DEVELOPMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS

Embryology

The development of the parotid gland includes a phase where the glandular endodermal anlage wraps itself around developing lymphatic elements while crossing other vascular structures and components of the branchial apparatus that form part of the face and neck. The incorporation of these structures persists into adult life and explains masses of the parotid that are of lymph node origin, vascular origin, or branchial origin. Warthin tumor, also known as parotid papillary cystadenoma lymphomatosum, is a neoplasm uniquely associated with the parotid glands, perhaps in part related to this development.

Applied Anatomy

Parotid Gland

The important anatomic considerations in parotid masses take into account the surrounding muscles, bones, vessels, and nerves that come in contact with the gland. Also, the parotid capsule attachments will direct the spread of both benign and malignant tumors. This anatomy should be reviewed in detail at this point, if necessary, in Chapter 175. The following anatomic relationships must be understood to properly ensure that imaging data is incorporated into the treatment of benign and malignant tumors:

- Facial nerve and the anatomic landmarks that relate to the surgical approach to facial nerve preservation; also, the relationships of the facial nerve to the fifth cranial nerve via the auriculotemporal nerve and greater petrosal nerve (Figs. 179.2 and 179.3)

- Attachments of the parotid capsule to the external auditory canal and external ear in general

- Deep relationships of the gland to the parapharyngeal spaces

- Parotid lymph nodes and their drainage patterns

- For very advanced lesions, the surrounding musculoskeletal relationships of the TMJ, mandible, temporal bone, and more central skull base to the parotid gland

Facial Nerve

The anatomic landmarks of prime importance in localizing the course of the facial nerve include the following:

- Descending facial canal

- Stylomastoid foramen

- Fat pad below the stylomastoid foramen (containing the nerve and vessels) (Fig. 179.3)

- Digastric groove and proximal portion of the posterior belly of the digastric muscle (Fig. 179.3)

- Tragal pointer (surgical jargon describing a part of the ear cartilage—the main trunk of the nerve typically lies about 10 mm inferior and 10 mm deep to the “pointer”) (Fig. 179.3)

- Superficial temporal artery and retromandibular vein (the nerve typically lies just lateral to the vein) (Fig. 179.3)

- Expected position of the division of the nerve into its major branches called the pes anserinus

The facial nerve itself is routinely visible throughout its course in the temporal bone and in the fat pad just below the stylomastoid foramen; it is occasionally visible in the gland on magnetic resonance (MR). It is relatively unimportant to see the nerve in the gland. It is definitely important to understand the surgical and imaging landmarks just described so that the relationship of disease processes to the facial nerve can be fully appreciated for diagnostic and treatment purposes.

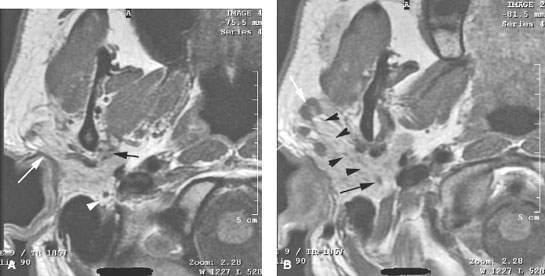

FIGURE 179.3. Several figures to review the normal course of the facial nerve within the parotid gland (discussed in more detail in Chapter 175). A–F: All are magnetic resonance (MR) studies. G–H are ultrasound. A: The tragal pointer, which is a landmark for identification of the facial nerve at surgery. It is known that the main trunk of the facial nerve will lie in the parotid substance about 1 cm inferior and 1 cm medial to this anatomic landmark (arrow). At this level, the facial nerve and/or its accompanying vessels can be seen within the fat pad below the stylomastoid foramen (arrowhead). B: The facial nerve as it enters the parotid gland (arrow) and travels through the substance of the gland (arrowheads). Normal intraparotid nodes are shown by the white arrows. C: T1-weighted image showing the main trunk of the facial nerve traveling within the parotid gland unusually well. Typically, the nerve is either not clearly visible in the gland or only short segments are visible. Notice how the nerve is headed lateral to the retromandibular vein (arrowhead). All of these are very reliable surgical landmarks of the position of the nerve within the gland. D–H: A patient with a benign mixed tumor intrinsic to the submandibular gland. MR images in (D) through (F) show the position of the typical-appearing benign mixed tumor to the predicted course of the facial nerve main trunk (shown in green). The ultrasound in (G) and (H) identifies the mass and shows its flow characteristics. However, the entire relationship of the mass relative to the plate plane of the facial nerve is likely less well understood than on the MR study in (D) through (F). One can predict that the nerve would lie between the mass (green line) and the retromandibular vein and external carotid artery (arrowhead).

IMAGING APPROACH

Techniques and Relevant Aspects

Computed Tomography

Specific computed tomography (CT) protocols for various indications appear in Appendix A and are discussed in more detail in Chapter 175. CT data sets should be obtained with about 1-mm collimation reconstructed at 1- to 3-mm slice thickness depending on the clinical situation. Such acquisitions will be suitable for adequate multiplanar reformations. If sections are too thin, there may be an important loss in low contrast resolution that may cause a lesion to “hide” within the tissue density of the normal glands. Such occasionally poor contrast between a salivary gland mass and the normal gland can be daunting, and in any questionable case, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be done to more confidently exclude a mass if one is strongly suspected clinically (Fig. 179.4). This issue makes MRI a better first choice for the evaluation of a parotid-region mass if there is no inflammatory component to the clinical presentation.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Specific MR protocols for various indications appear in Appendix B. MRI should be done with 3-mm sections and a field of view of 12 to 16 cm. Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) may be used since such imaging may contribute information about the likely benign or malignant nature of the mass. However, it is unlikely that any serious clinical decision will be based on such data relative to that from the clinical setting, anatomic imaging, and biopsy.

Since it is not predictable when contrast might be useful, a parotid-region study is generally done with acquisitions before and after contrast injection. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance (CEMR) studies are clearly useful when cranial nerves V and VII must be evaluated, if the lesion is aggressive, and/or if the cervical nodes are to be evaluated. Fat suppression is very useful on both the T1- and T2-weighted sequences.

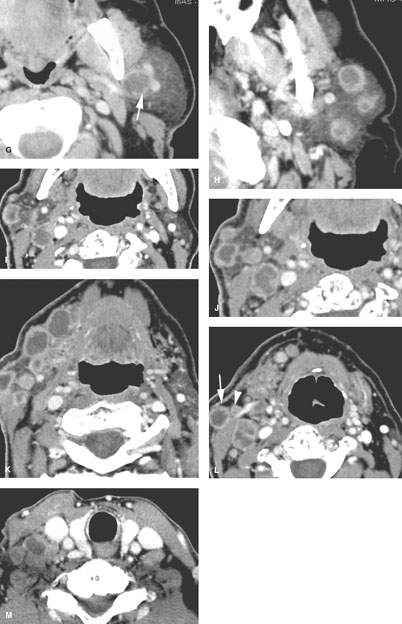

FIGURE 179.4. Four patients with benign mixed tumors with variable morphologic features reflecting the complex cellular constituents of these pleomorphic adenomas. A: Patient 1 with a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) study showing a heterogeneously enhancing mass superficial to the main trunk of the facial nerve. B: Patient 2 with a CECT showing a partially enhancing (arrowhead) and partially calcified (arrow) mass superficial to the expected position of the main trunk of the facial nerve (shown by the green line). C: Patient 3 with a CECT showing a mass (arrow) almost isodense to the normal parotid tissue and deep to the expected position of the main trunk of the facial nerve (shown by the green line). D: Patient 4 with a CECT showing a mass (arrow) almost isodense to the normal parotid tissue and superficial to the expected position of the main trunk of the facial nerve (shown by the green line).

FIGURE 179.5. A patient who had a fluorine-18 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) showing avid uptake of a parotid-region mass. This contrast-enhanced computed tomography study showed it to have nonaggressive morphologic features (arrow). It was removed and identified as a benign mixed tumor. (NOTE: This study illustrates significant limitations of FDG positron emission tomography in salivary gland tumors. Benign lesions may show avid activity, while malignant lesions may not show evidence of increased metabolic activity.)

Radionuclide Studies

Radionuclide studies are not used routinely for the evaluation of parotid gland masses. Those using technetium, iodine, and fluorine-18 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) are used in highly selected circumstances (Fig. 179.5).

Ultrasound

Standard scanning techniques as described in Chapter 4 are used.

Conventional Sialography

Conventional sialography is no longer used to evaluate parotid-region masses.

Pros and Cons

General Approach

Magnetic Resonance and Computed Tomography

MR and CT are the most used imaging studies to evaluate a parotid-region mass. Such expensive studies may not be necessary if the mass is discrete and freely mobile. The clinician should be aware that on physical examination, superficial masses may be easily misinterpreted as a subcutaneous lesion and result in an unpleasant surprise during resection. Pleomorphic adenomas are notorious for such presentation. If there is a hint of a parotid inflammatory condition clinically in the presence of a mass, then CT is preferred over MR.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound (US) may be used to determine whether superficial lesions are intrinsic or extrinsic to the parotid gland and to follow such masses if it is likely a reactive node (Figs. 179.1D and 179.3G–H) or if its benign nature is established by biopsy and definitive surgery is not elected. US may be used to guide percutaneous biopsies of the parotid gland that cannot be done by palpation alone. It also improves the diagnostic yield of the specimen by ensuring that the sampling is from the mass and not surrounding normal gland. The combination of US and biopsy can be a very quick and cost-effective way to evaluate a superficial mass that is likely to be benign or related to an enlarged periparotid or intraparotid lymph node. The US is limited by the skill of the operator and limited penetration between the bony structures of ramus of the mandible and mastoid portion of temporal bone.

Radionuclide Studies

Radionuclide studies are not used routinely for the evaluation of parotid gland masses. The constraints on its utility are discussed in more detail in Chapter 5 in general and with regard to glandular neoplasms in Chapter 22. Technetium, iodine, and FDG activity are frequently seen in normal glands (Fig. 5.9). FDG uptake is variable in both benign and malignant salivary gland neoplasms, somewhat limiting the utility of fluorine-18 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) studies in patients with salivary gland masses (Fig. 179.5).

Specific Indications

Parotid-Region Masses

Define the origin and extent of a parotid-region mass: Is it intrinsic or extrinsic to the parotid gland? If the margins of a mass are not clearly defined during physical examination, CT or MR should be done. This will help to determine whether the point of origin of the mass is intrinsic or extrinsic to the gland. Since “parotid masses” are frequently of nonparotid origin (Table 175.1), the relationship of the mass to the gland markedly alters the management in as many as a third of patients presenting with a parotid-region mass (Figs. 179.1 and 179.2). As a result, imaging can quickly narrow the diagnostic possibilities by excluding the extrinsic causes of parotid-region masses.

Determine whether the lesion present is solitary versus multiple and unilateral versus bilateral: The imaging determines whether the abnormality is a unilateral or bilateral, and whether it is multifocal on one or both sides (Table 179.1). A bilateral abnormality may be diffuse and is likely to represent systemic processes such as viral infection (human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], mumps), lymphoma, or autoimmune sialoadenitis (Chapter 177), and, for the purposes of this chapter, mass-inducing complications of systemic disease such as lymphoepithelial cysts in HIV and frankly neoplastic complications such as lymphoma arising in chronic autoimmune sialoadenitis (Figs. 179.6A–F and 179.7). Imaging can reveal more localized multifocal masses such as Warthin tumors (Fig. 179.6I–L), parotid adenopathy due to regional metastatic skin cancer (Fig. 179.1F–H), and a primary parotid carcinoma with parotid adenopathy (Fig. 179.8).

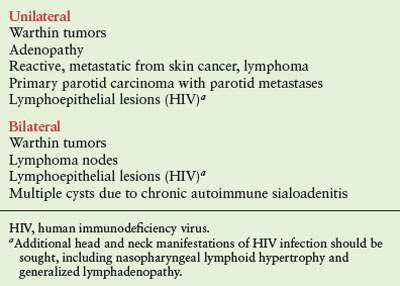

TABLE 179.1. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF MULTIPLE PAROTID MASSES

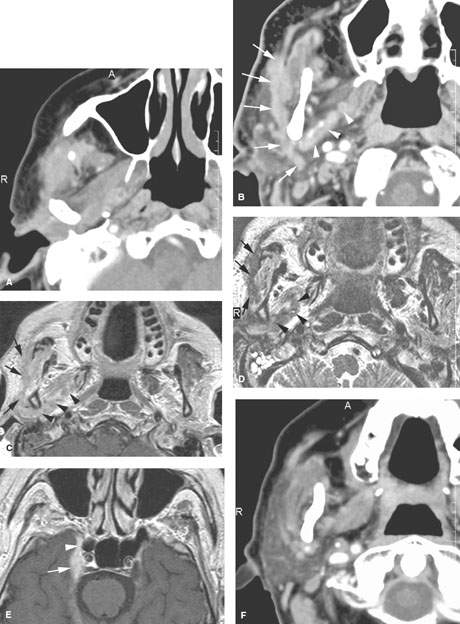

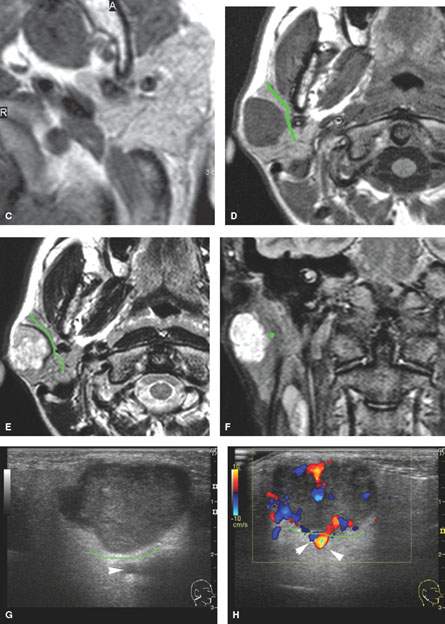

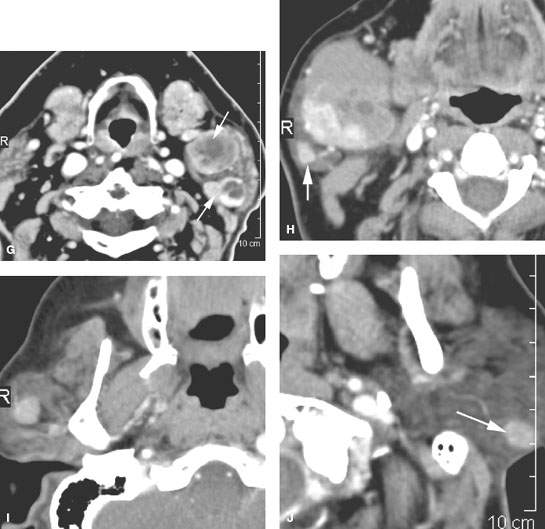

FIGURE 179.6. Illustrations in four patients of how multiple or bilateral abnormalities can lead to a group of specific considerations for parotid-region masses and may alert the clinician to possible complications of systemic disease that might produce parotid-region neoplasms. A–D: Patient 1 had a right parotid region mass. Magnetic resonance was done. In (A), the contrast-enhanced T1-weighted (T1W) image shows a diffuse infiltrating mass in the right parotid gland and a smaller nonpalpable mass on the left. In (B), the main mass seems to be associated with a small intraparotid lymph node (arrow), and a generally nodular infiltrating pattern is seen in the left parotid gland. The contrast-enhanced T1W image in (C) shows all of the abnormalities to generally enhance. The T2-weighted image in (D) shows the findings to be of generally increased signal intensity similar to fat. (NOTE: This case illustrates how the bilateral nature of disease points to a systemic abnormality in this patient with autoimmune parotid disease. The overall findings suggest a complicating lymphoma, which was confirmed bilaterally in this patient.) E, F: Patient 2 presenting with bilateral parotid-region masses. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) study shows these changes to be due to mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma as a complication of chronic autoimmune salivary disease. The associated adenopathy (arrows in F) were a clue to the presence of lymphoma, although all of the changes seen here could have just been due to severe autoimmune disease. G: Contrast-enhanced CT study in Patient 3 presenting with a left parotid tail mass that had increased acutely in size. The responsible lesion was a hemorrhagic Warthin tumor (arrow). A second separate Warthin tumor was present. The unilateral but multiple nature and location points to the Warthin tumor as the most likely etiology. In the proper circumstance, these masses could also be due to metastatic parotid adenopathy. H–J: Patient 4 presenting with a parotid tail–region mass that was slowly enlarging. The larger mass presents an appearance somewhat atypical for Warthin tumor (H). The second nodule at the parotid tail (arrow) raised the possibility of a second Warthin tumor or possibly a primary epithelial neoplasm represented by a larger mass and a secondary metastatic parotid lymph node. In (I) and (J), there are additional parotid masses on each side. These were confirmed to be multiple Warthin tumors.

Define the relationship of an intrinsic parotid mass to the facial nerve and its major branches: At the minimum, the imager should be able to determine the superficial or deep relationship of the mass relative to the main trunk of the facial nerve (Figs. 175.8, 175.9, 179.3, and 179.8–179.12). With more effort, it is possible to refine the location of the parotid mass in relation to the surgical landmarks commonly used to identify the trunk of the facial nerve during dissection. As expertise grows, one can reasonably predict the position of the main branches of the facial nerve within the substance of the gland (Fig. 179.13).

Characterize the type of lesion by the degree of invasiveness present both within and beyond the parotid gland: One must determine the full extent of the lesion and its potential for invasiveness. The criteria used to evaluate for a malignant process include the margins of the lesion, internal signal characteristics on T2-weighted images, and perhaps behavior on DWI (Figs. 179.3–179.13). Metastatic adenopathy (Fig. 179.8) and perineural spread are almost sure indicators of a malignant neoplasm (Fig. 179.10).

In advanced cancers, findings such as bone erosion (Fig. 179.14), fixation to the deep neck (Fig. 179.15A) and skull base and carotid encasement (Fig. 179.15B) may dramatically alter the treatment approaches and prognosis.

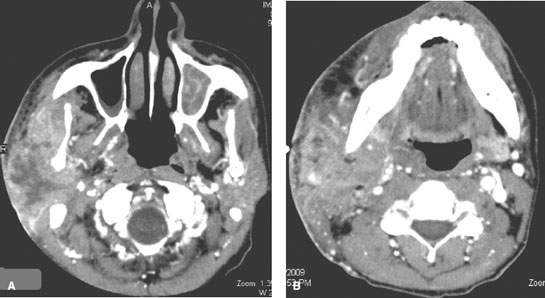

FIGURE 179.7. A, B: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography study of an human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patient presenting with a very aggressive primary parotid-region lymphoma likely due to disease developing within a chronically HIV-infected parotid gland.

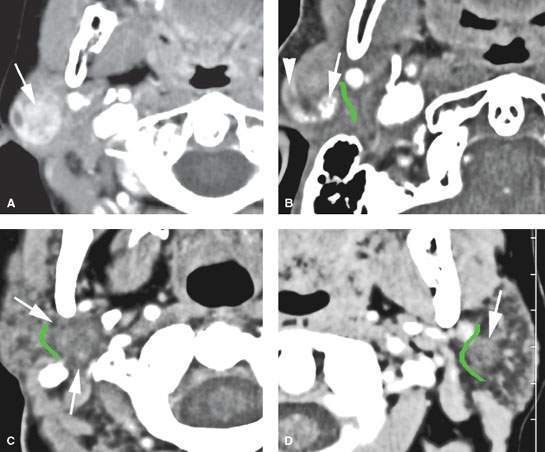

FIGURE 179.8. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) studies in two patients with parotid-region masses shown to be due to primary epithelial carcinomas. A–D: Patient 1. Primary tumor is indicated by the arrows in (A) and (B). Multiple nodules are present, indicated by arrowheads in (B) and (C), representing intraparotid metastatic adenopathy. Most of the nodes show focal defects, and some of them show signs of early extranodal extension (arrowheads). E–H: Patient 2. The CT study shows a well-circumscribed mucoepidermoid carcinoma. In (E), the tumor appears to be well circumscribed with a fluid density center. However, there is an enhancing structure more laterally. That was eventually proven to be spread of tumor along the facial nerve. Even though the primary appears to be fairly well circumscribed, histology showed this to be a high-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Additional evidence of the aggressive nature of this tumor is seen in (F) through (H), where multiple metastatic lymph nodes are present at the parotid tail, along the external jugular chain (arrowheads in F), and in levels 3, 4, and 5 (arrows in G and H). (NOTE: The pattern of adenopathy in primary parotid cancers is much like that seen in lymph node metastases in skin cancer, and both of these conditions have to be considered when such spread patterns are present.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree