Part 2 Pancreas and Spleen

Case 45

Key Finding

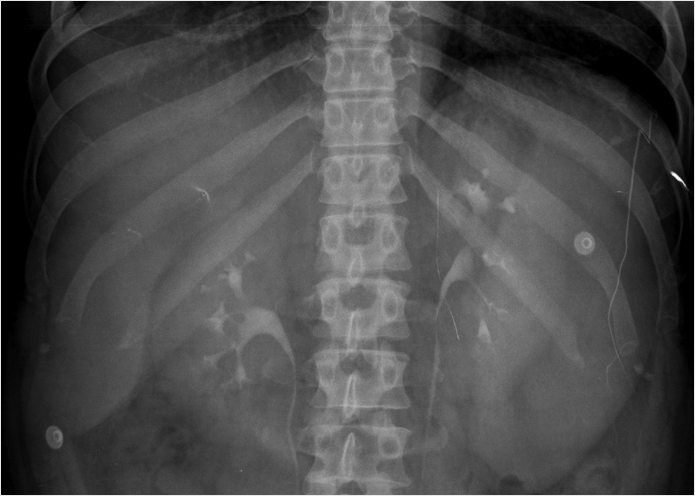

Central abdominal grouped calcifications.

Diagnosis

Chronic pancreatitis: Chronic pancreatitis is the most common cause of pancreatic parenchymal calcifications. It is most commonly related to alcoholic pancreatitis. These calcifications typically are subcentimeter in size and spherical to oval in morphology. Chronic pancreatitis is caused by repeated episodes of pancreatic inflammation, which can cause proteinaceous material and calcium carbonate to obstruct small ducts resulting in ductal ectasia and progressive periductal fibrosis. These parenchymal calcifications are easily seen on X-rays.

On cross-sectional imaging, other findings of chronic pancreatitis may be seen including pancreatic ductal dilation and pancreatic atrophy. The most common finding in chronic pancreatitis is ductal dilation. The ducal dilation can often involve dilated side branches (which are typically seen in the body of the pancreas and are perpendicular to the long axis of the main duct). The key finding on an X-ray is noting calcifications in the anatomical location of the pancreas. Therefore, other diagnoses are highly unlikely such as calcified lymph nodes (spherical with an egg-shell appearance) and arteriosclerosis (linear following arterial distributions).

✓ Pearls

Pancreatic parenchymal calcifications are a classic X-ray finding of chronic pancreatitis.

Chronic pancreatitis is typically related to alcoholism.

Arterial calcifications are linear and should not be confused for chronic pancreatitis.

Suggested Readings

Federle MP, Jeffrey RB, Woodward PJ, Borhani A. Diagnostic Imaging: Abdomen. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009 Javadi S, Menias CO, Korivi BR, et al. Pancreatic calcifications and calcified pancreatic masses: pattern recognition approach on CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017; 209(1):77–87Case 46

Key Finding

Left upper quadrant calcifications.

Top 3 Differential Diagnoses

Pancreatic calcifications: Chronic pancreatitis is the most common cause of pancreatic parenchymal calcifications and most commonly related to alcoholic pancreatitis. Look for small irregular calcific densities in the anatomical location of the pancreas. Less commonly, pancreatic calcifications can be due to cystic fibrosis, neuroendocrine tumors (e.g., insulinomas), and pancreatic cancer.

Nephrolithiasis: Most renal stones are calcium based with the most common being calcium oxalate. Calcium stones are seen on X-rays and typically are oval in shape and overlying the kidney silhouette. Less commonly, the morphology may be staghorn when composed of magnesium ammonium phosphate (struvite stone). The majority of patients will present with hematuria and flank pain.

Splenic calcifications: Most commonly healed granulomatous infections from histoplasmosis, tuberculosis, brucellosis, toxoplasmosis, candidiasis, and fungal infections. Histoplasmosis is the most common in the United States and typically presents with multiple small round calcifications. Calcific densities overlying the splenic silhouette are seen on an X-ray.

Additional Diagnostic Considerations

Atherosclerosis: Atherosclerotic disease (ASD) appears as curvilinear parallel lines of calcification in the expected location of vascularity. Considering left upper quadrant calcifications, splenic artery involvement is a consideration but is usually tortuous.

Ingested pills/foreign bodies: The key to diagnosis is the angular margins and irregular nonanatomical morphologies. Swallowed pills/objects will most likely move location on repeat studies. Metallic objects will be more radiopaque compared to bones and calcic densities.

Diagnosis

Splenic granulomas.

✓ Pearls

Nephrolithiasis on an X-ray should be further evaluated on ultrasound/CT to exclude obstructive uropathy.

Pancreatic calcifications are one of the three findings of chronic pancreatitis.

Splenic granulomas are benign and require no follow-ups.

Suggested Readings

Dyer RB, Chen MY, Zagoria RJ. Classic signs in uroradiology. Radiographics. 2004; 24(Suppl 1):S247–S280 Federle MP, Jeffrey RB, Woodward PJ, Borhani A. Diagnostic Imaging: Abdomen. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009 Guelfguat M, Kaplinskiy V, Reddy SH, DiPoce J. Clinical guidelines for imaging and reporting ingested foreign bodies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014; 203(1):37–53 Javadi S, Menias CO, Korivi BR, et al. Pancreatic calcifications and calcified pancreatic masses: pattern recognition approach on CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017; 209(1):77–87 Thipphavong S, Duigenan S, Schindera ST, Gee MS, Philips S. Nonneoplastic, benign, and malignant splenic diseases: cross-sectional imaging findings and rare disease entities. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014; 203(2):315–322Case 47

Key Finding

Spleen inferior margin extends below the left renal shadow.

Diagnosis

Splenomegaly: Splenomegaly is defined as a spleen larger than 14 cm. It can be diagnosed on X-ray when the inferior splenic margin extends below the left renal shadow. Common causes for splenomegaly include portal hypertension, anemia, infection, and tumor. Portal hypertension is the most common cause of splenomegaly that is classically due to hepatic cirrhosis. Any cause of extramedullary hematopoiesis can result in hepatosplenomegaly. Hemolytic anemias such as thalassemia enlarge the spleen due to sequestration of red blood cells. A common infectious cause of splenomegaly is mononucleosis from Epstein–Barr virus. Any tumor can result in spleen enlargement. Lymphoma is the most common malignancy in the spleen. Primary splenic lymphoma is much less common than secondary lymphoma (commonly seen in HIV/AIDS [human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome] patients). Hemangiomas are the most common benign splenic neoplasms and when large can result in splenomegaly. When splenomegaly is suspected on X-ray, it should be further investigated with cross-sectional imaging.

✓ Pearls

Spleen greater than 14 cm is splenomegaly.

The most common cause of splenomegaly is portal hypertension.

Splenomegaly on X-ray should be further investigated with cross-sectional imaging.

Suggested Readings

Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Alliance, Australasian Leukaemia and Lymphoma Group, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Consortium, Italian Lymphoma Foundation, European Organisation for Research, Treatment of Cancer/Dutch Hemato-Oncology Group, Grupo Español de Médula Ósea, German High-Grade Lymphoma Study Group, German Hodgkin’s Study Group, Japanese Lymphorra Study Group, Lymphoma Study Association, NCIC Clinical Trials Group, Nordic Lymphoma Study Group, Southwest Oncology Group, United Kingdom National Cancer Research Institute. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014; 32(27):3059–3068 Federle MP, Jeffrey RB, Woodward PJ, Borhani A. Diagnostic Imaging: Abdomen. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009 Thipphavong S, Duigenan S, Schindera ST, Gee MS, Philips S. Nonneoplastic, benign, and malignant splenic diseases: cross-sectional imaging findings and rare disease entities. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014; 203(2):315–322Case 48

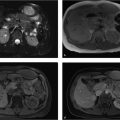

Key Finding

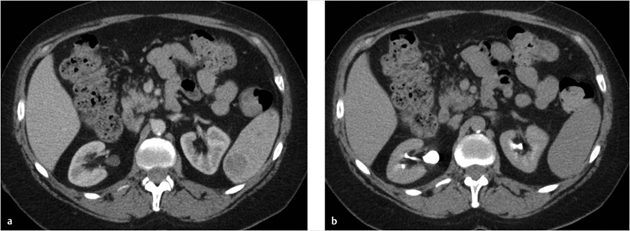

Pancreatic duct dilatation.

Top 3 Differential Diagnoses

Acute pancreatitis: Interstitial edematous pancreatitis represents majority of pancreatitis. The focal or diffuse pancreatic edema can result in portions of the narrowing and poststenotic dilation. When pancreatitis is focal (e.g., groove pancreatitis), it can mimic a mass. Cross-sectional imaging is only used to evaluate the severity of disease. Pancreatitis is a clinical and laboratory diagnosis. Patients usually present with epigastric pain radiating to the back. Acute pancreatitis is usually treated with bowel rest (nothing by mouth, NPO) and supportive therapy. Surgical intervention may be needed in advanced cases.

Chronic pancreatitis: Multiple bouts of pancreatitis over time can lead to chronic extrahepatic ductal dilation. The classic triad of findings of chronic pancreatitis is parenchymal calcifications, parenchymal atrophy, and ductal dilation (> 4 mm). Another chronic pancreatitis finding is side branch ductal dilation. The most common etiology is chronic alcoholism.

Neoplasm: Tumors such as cholangiocarcinoma, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, gallbladder malignancies, and metastasis may invade the biliary system. Malignant tumors involving the common bile duct create an abrupt caliber change with shouldering and asymmetry. There is usually a transition point between the dilated obstructed duct and the smaller caliber decompressed duct. Extrinsic compression from malignant masses, lymphadenopathy, or dilated collateral vasculature may also produce poststenotic ductal dilation.

Additional Diagnostic Considerations

Papillary stenosis: Defined as obstruction of bile flow at the sphincter of Oddi without the presence of a mass or inflammation at the ampulla, papillary stenosis appears as common bile duct dilation on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). The most common cause is dysfunction of the sphincter of Oddi and patients typically present clinically with jaundice and pancreatitis. Papillary size less than 12 mm suggests an underlying benign cause. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is useful in determining the cause.

Diagnosis

Chronic pancreatitis.

✓ Pearls

Acute pancreatitis cannot be diagnosed on imaging without peripancreatic fat stranding.

Chronic pancreatitis is the diagnosis when the triad of parenchymal calcifications, atrophy, and ductal dilation is seen.

Neoplasm must be excluded when pancreatic ductal dilation is seen.

Suggested Readings

Leyendecker JR, Elsayes KM, Gratz BI, Brown JJ. MR cholangiopancreatography: spectrum of pancreatic duct abnormalities. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002; 179(6):1465–1471 Nikolaidis P, Hammond NA, Day K, et al. Imaging features of benign and malignant ampullary and periampullary lesions. Radiographics. 2014; 34(3):624–641 O’Connor OJ, O’Neill S, Maher MM. Imaging of biliary tract disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011; 197(4):W551–8Case 49

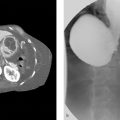

Key Finding

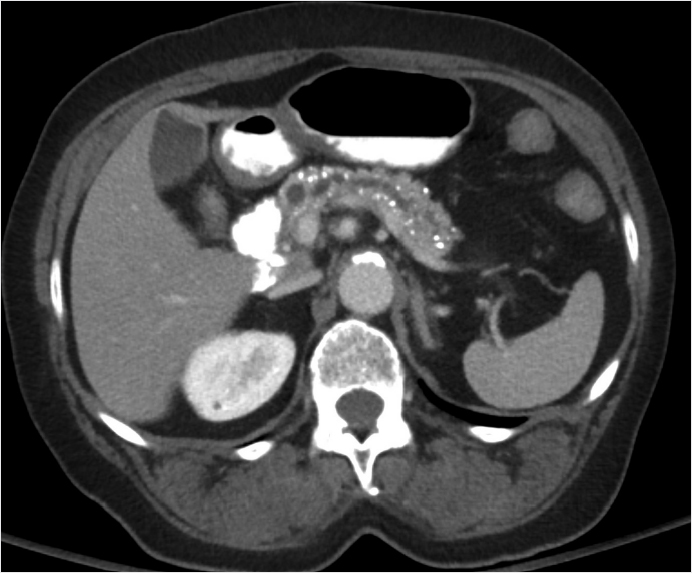

Solitary solid splenic lesion.

Top 3 Differential Diagnoses

Infarct: An infarction can mimic a solid mass; however, there will be no internal enhancement. Capsular enhancement may be observed. The classical appearance is similar to that of other organs as a peripherally based wedge-shaped hypodensity. Atypical presentations such as an irregular or linear shape are common. Extension to the capsular is a more reliable indicator but not always seen. Many infarcts are occult by imaging. The cause may be idiopathic or from a predisposing factor such as sickle-cell disease or embolic phenomenon.

Hemangioma: This benign mass is the most common primary splenic neoplasm. The characteristic liver findings of peripheral nodular discontinuous enhancement pattern and high T2 signal on MR are less commonly seen in the spleen. The CT appearance is often homogeneously hypodense lesion with soft-tissue attenuation. On delayed imaging, the lesion can become isodense to the spleen. Central punctate or peripheral curvilinear calcifications can also present. The imaging appearance is indistinguishable from hamartoma (which is rare). This usually has no clinical significance; however, in large lesions thrombocytopenia from Kasabach–Merritt syndrome (consumptive coagulopathy) can rarely occur.

Lymphoma: This is the most common malignancy to affect the spleen. A solitary hypodense mass is one of four major appearances in the spleen. The others include diffuse infiltration, multiple focal lesions, and miliary involvement. Primary splenic lymphoma is often associated with AIDS. Concurrent adenopathy is helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis.

Additional Diagnostic Considerations

Solitary Metastasis: Hematogenous metastasis occurs due to the rich arterial supply, although they are infrequent compared to liver metastasis. The imaging appearance can range from solid to cystic, single lesions or multiple, with variable enhancement. Most commonly these are from melanoma, breast, lung, gastrointestinal, or ovarian malignancies.

Angiosarcoma: Rare, however the most common primary malignancy of the spleen after lymphoma. Splenomegaly should also be present. There is high metastatic potential to multiple organs and a poor prognosis.

Diagnosis

Hemangioma.

✓ Pearls

Splenic hemangiomas are frequently atypical but may retain contrast on delayed images.

Extrasplenic manifestations are helpful in detecting lymphoma or metastases.

Consider infarction if there is no appreciable enhancement.

Suggested Readings

Luna A, Ribes R, Caro P, Luna L, Aumente E, Ros PR. MRI of focal splenic lesions without and with dynamic gadolinium enhancement. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006; 186(6):1533–1547 Ricci ZJ, Mazzariol FS, Flusberg M, et al. Improving diagnosis of atraumatic splenic lesions, part II: benign neoplasms/nonneoplastic mass-like lesions. Clin Imaging. 2016; 40(4):691–704 Thipphavong S, Duigenan S, Schindera ST, Gee MS, Philips S. Nonneoplastic, benign, and malignant splenic diseases: cross-sectional imaging findings and rare disease entities. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014; 203(2):315–322Case 50

Key Finding

Pancreatic calcifications.

Top 3 Differential Diagnoses

Chronic pancreatitis: Repeated episodes of inflammation cause proteinaceous material and calcium carbonate to obstruct small ducts, resulting in ductal ectasia and progressive periductal fibrosis. This results in the classic appearance of irregular ductal dilation (68%) often including side branches, parenchymal and intraductal calcifications (54%), and parenchymal atrophy (50%). Patients usually have a history of chronic alcoholism (70% of cases), obstructing biliary stones, chronic smoking, or cystic fibrosis.

Vascular: Calcified atheromatous plaque along the course of the splenic artery, gastroduodenal, superior mesenteric, and pancreaticoduodenal branches may mimic and are more common than parenchymal calcifications. These calcifications have tram track configuration. Focal aneurysms, most commonly splenic, have usual peripheral or eggshell calcifications. Chronic venous thrombosis, usually superior mesenteric vein (SMV) or splenic, may have intraluminal calcification and mural thickening.

Choledocholithiasis: Coexisting biliary dilatation, cholelithiasis (95%), and clinical obstructive jaundice. The gold standard is endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) but magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) sensitivity and specificity are both 80 to 100%. CT “bull’s-eye” sign with rim of low-density bile around calcified stone is 60 to 80% sensitive. Choledocolithiasis is usually solitary, but when multiple, they are clustered typically within the distal common bile duct.

Additional Diagnostic Considerations

Serous cystadenoma (SCA): Complex microcystic, multilocular cystic lesion with a “honeycomb” appearance, typically more than six locules each less than 2 cm, usually less than 1 cm, and may be so small as to give appearance of solid lesion. A central scar is present in 20 to 30% with calcifications. It presents in the sixth to seventh decade in women. Vascular encasement and ductal dilation are rare.

Islet cell/neuroendocrine tumor: These appear as hypervascular tumors with intense arterial phase enhancement. Calcifications are seen in 20% usually either with insulinomas or larger nonfunctional tumors (usually coarse irregular central calcification). Lesions less than 3 cm are more likely to be functional or syndromic. Insulinoma is the most common representing 50% of these tumors.

Other tumors: Pancreatic adenocarcinoma very rarely has calcifications. Mucinous tumors such as intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) and mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN) have calcifications in 16 to 20% peripheral or septal. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms have calcifications in 50% but this tumor is rare, always in women less than 35 years of age.

Diagnosis

Chronic pancreatitis.

✓ Pearls

Pancreatic calcifications, atrophy, and ductal dilatation are characteristic of chronic pancreatitis.

Vascular calcifications are most common overall with a typical tram track configuration and intravenous contrast will typically define the vessel of origin.

Choledocholithiasis on ultrasound can be confirmed with either MRCP or ERCP.

Suggested Readings

Anderson SW, Lucey BC, Varghese JC, Soto JA. Accuracy of MDCT in the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006; 187(1):174–180 Lesniak RJ, Hohenwalter MD, Taylor AJ. Spectrum of causes of pancreatic calcifications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002; 178(1):79–86 Miller FH, Keppke AL, Wadhwa A, Ly JN, Dalal K, Kamler VA. MRI of pancreatitis and its complications: part 2, chronic pancreatitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004; 183(6):1645–1652Case 51

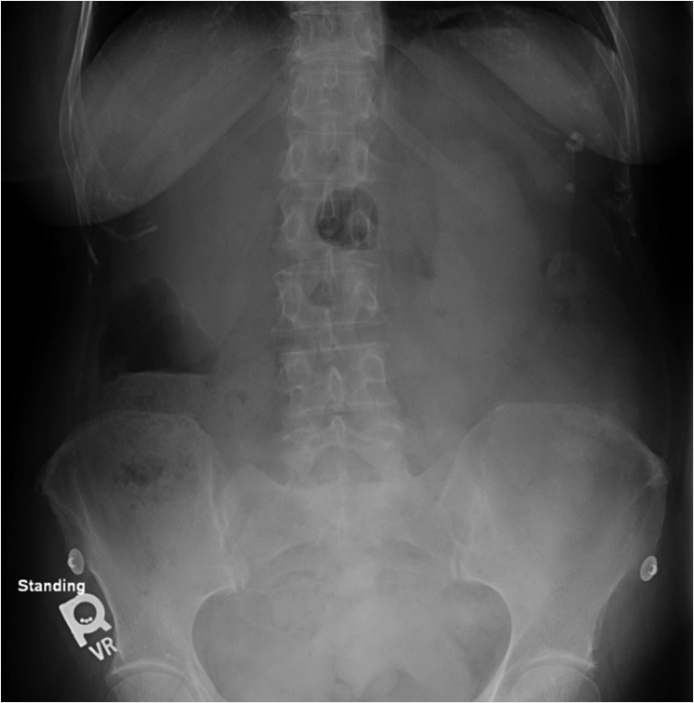

Key Finding

Global enlargement of the spleen.

Top 3 Differential Diagnoses

Portal hypertension: Portal hypertension is the most common cause of splenomegaly. This is classically due to hepatic cirrhosis; however, other causes of portal hypertension include right-sided heart failure, portal vein thrombosis, Budd–Chiari syndrome, and hepatic fibrosis. MRI may demonstrate characteristic Gamma–Gandy bodies, seen as multiple foci of low T1 and T2 signal. Clinch the diagnosis with associated findings of cirrhosis such as a shrunken liver with nodular surface contour, ascites, and varices.

Lymphoma: Lymphoma is most common malignancy in the spleen. The imaging appearance includes diffuse splenic enlargement, solitary mass, or multiple masses. Other patterns of splenic involvement include solitary mass, multiple masses, or miliary appearance. Enlarged extrasplenic lymph nodes are typically seen. Primary splenic lymphoma is much less common than secondary lymphoma, and should prompt consideration for HIV/AIDS (human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). Leukemia is typically a diffuse infiltrative process that can result in massive splenomegaly.

Infection: Infectious splenomegaly often has concurrent hepatomegaly. Consider mononucleosis from Epstein–Barr virus in a young and otherwise healthy patient. In this context, the spleen is particularly susceptible to rupture. Splenomegaly in parasitic involvement can be due to sequestration of the parasitic agent or the immunoglobulin M response from splenic infiltration. Bacterial and fungal etiologies typically result in focal lesions rather than splenomegaly.

Additional Diagnostic Considerations

Hematologic disorders: Any cause of extramedullary hematopoiesis can result in hepatosplenomegaly. Hemolytic anemias such as thalassemia are also a cause due to increased sequestration of defective red blood cells. Early in life sickle-cell disease causes splenic enlargement; however, eventually autosplenectomy occurs from repeated infarction.

Sarcoidosis: Hepatosplenomegaly is a frequent manifestation. Numerous hypodense lesions, calcifications, and adenopathy may also be present.

Diagnosis

Splenomegaly secondary to leukemia.

✓ Pearls

Differential for splenomegaly is vast, look for associated imaging findings such as hepatomegaly and adenopathy to narrow the etiologies.

Splenomegaly often results in convexity of the medial surface (normally concave).

Complications include splenic rupture and hyperfunctioning spleen resulting in pancytopenia (hypersplenism).

Suggested Readings

Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Alliance, Australasian Leukaemia and Lymphoma Group. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Consortium. Italian Lymphoma Foundation. European Organisation for Research, Treatment of Cancer/Dutch Hemato-Oncology Group, Grupo Español de Médula Ósea, German High-Grade Lymphoma Study Group, German Hodgkin’s Study Group, Japanese Lymphorra Study Group, Lymphoma Study Association, NCIC Clinical Trials Group, Nordic Lymphoma Study Group, Southwest Oncology Group, United Kingdom National Cancer Research Institute. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014; 32(27):3059–3068 Federle MP, Jeffrey RB, Woodward PJ, Borhani A. Diagnostic Imaging: Abdomen. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009 Thipphavong S, Duigenan S, Schindera ST, Gee MS, Philips S. Nonneoplastic, benign, and malignant splenic diseases: cross-sectional imaging findings and rare disease entities. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014; 203(2):315–322Case 52

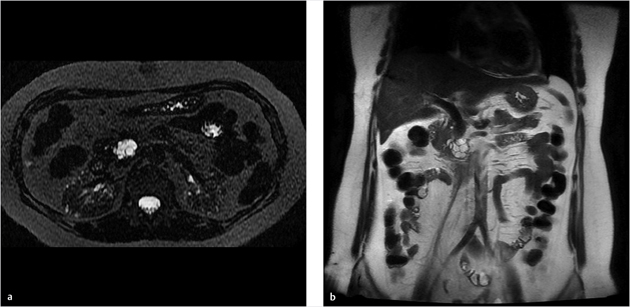

Key Finding

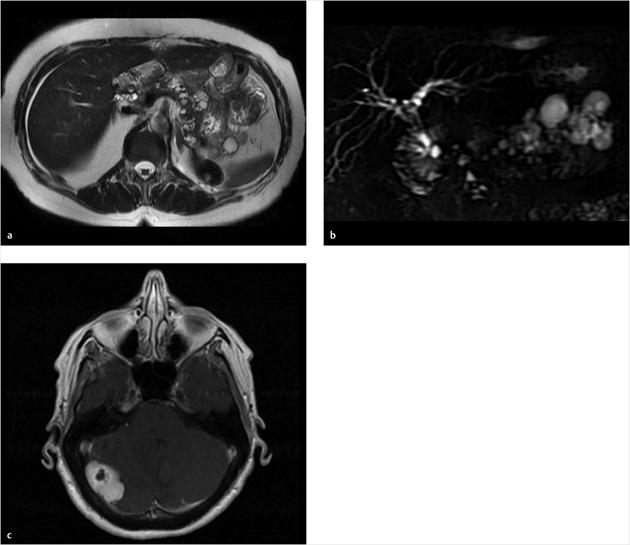

Multiple pancreatic cysts.

Top 3 Differential Diagnoses

Pseudocysts: The most common pancreatic cystic lesion and most commonly are multiple. These are the sequelae of pancreatitis beginning as acute peripancreatic fluid collections that persist after 4 weeks organizing with an enhancing pseudocapsule and no internal complex septations or any soft-tissue nodules. Ductal communication is often visible. Pseudocysts may appear complex if complicated by infection or hemorrhage. Present in 20 to 40% of cases of chronic pancreatitis. Most are asymptomatic and nearly 40% will regress spontaneously with no intervention. Complications, symptoms, and failure to regress are more common with size greater than 4 cm.

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN): Side branch ductal type IPMN have a unilocular or multilocular cluster of grapes appearance, typically smaller than 3 cm, may communicate with main duct, calcifications in 20%, and typically low grade. There may be multiple small separate clusters suggestive of this diagnosis. Main duct type presents as irregular diffuse ductal dilation usually not as a focal lesion. Both types are present in older patients (sixth to seventh decade). Features of malignant conversion include large size greater than 3 cm, mural nodularity, main duct dilatation greater than 1 cm, mural nodularity, peripheral wall thickening or enhancement, and developing focal distal pancreatic atrophy.

Congenital cysts: Rare, less than 1% of pancreatic cystic lesions, with simple unilocular cysts either solitary or multiple throughout the pancreas. No ductal communication, nodules, calcifications, or septations. These are associated with congenital disorders such as autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPCKD), von Hippel–Lindau disease, and cystic fibrosis. Other characteristic imaging features of these disorders offer a clue to diagnosis, such as numerous renal/hepatic cysts for ADPCKD, central nervous system hemangioblastomas, pheochromocytomas, or renal cell carcinoma (RCC) for von Hippel–Lindau, or diffuse fatty replacement of pancreas with cystic fibrosis. There is no neoplastic potential and rarely are symptomatic.

Diagnosis

Congenital cysts secondary to von Hippel–Lindau.

✓ Pearls

Pseudocysts are the most common pancreatic cysts.

IPMN side branch type will have discrete separate clusters of cysts with ductal communication.

Congenital cysts are rare, simple, unilocular and have other imaging findings characteristic of the underlying congenital disorder.

Consider a solitary cluster of cysts as a single complex mass and distinct from this differential. More likely to be neoplastic, either microcystic or macrocystic, in morphology.

Suggested Readings

Demos TC, Posniak HV, Harmath C, Olson MC, Aranha G. Cystic lesions of the pancreas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002; 179(6):1375–1388 Kalb B, Sarmiento JM, Kooby DA, Adsay NV, Martin DR. MR imaging of cystic lesions of the pancreas. Radiographics. 2009; 29(6):1749–1765 Sahani DV, Kambadakone A, Macari M, Takahashi N, Chari S, Fernandez-del Castillo C. Diagnosis and management of cystic pancreatic lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013; 200(2):343–354Case 53

Key Finding

Multilocular cystic pancreatic head/uncinate lesion.

Top 3 Differential Diagnoses

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN): Side branch ductal type IPMN have a unilocular or multilocular cluster of grapes appearance, typically smaller than 3 cm, may communicate with main duct, calcifications in 20%, and typically low grade. Main duct type presents as irregular diffuse ductal dilation usually not as a focal mass/cysts. Both types are present in older patients (sixth to seventh decade). Worrisome features for conversion to invasive malignancy requiring resection include large size greater than 3 cm, mural nodularity, main duct dilatation greater than 1 cm, mural nodularity, peripheral wall thickening or enhancement, and developing focal distal pancreatic atrophy.

Serous cystadenoma (SCA): Complex microcystic, multilocular cystic lesion with a “honeycomb” appearance, typically more than six locules each less than 2 cm, usually less than 1 cm, and may be so small, as to give one the appearance of solid lesion. A central scar is present in 20 to 30% with calcifications. SCA presents sixth to seventh decade in women, 3:1 over men, and 70% found in body/tail and 30% in pancreatic head. The cyst content is high glycogen, low mucin, and low CEA (< 5 ng/mL). SCA has a low malignant potential and is usually followed with serial imaging. It is resected when it is larger than 4 cm or becomes symptomatic.

Mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN): Unilocular or multilocular cystic mass with septations, which may be thick or calcify, no main duct communication and is considered premalignant. Any mural nodularity suggests conversion to invasive malignancy. Typically, MCN is oligocystic with less than six locules that are macrocystic, less than 2 cm each. Most are in the pancreatic body and tail. It is most commonly seen in women (fourth to sixth decade). Cystic contents include elevate mucin, absent glycogen, and elevated CEA (> 192 ng/mL). Resection is usually performed due to the malignant potential.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree