Part 7: Soft Tissue Tumors

Case 93

Clinical History

A 51-year-old man referred for a history of a “firm, slowly growing popliteal cyst” (Fig. 93‑1).

Key Finding

Fusiform mass, with longitudinal “tail” entering and exiting eccentrically.

Top 3 Differential Diagnoses

Benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor: Benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors (BPNSTs) are classified into two general types among patients without neurofibromatosis: schwannomas (also termed neurilemmomas) and neurofibromas.

Both types of BPNSTs can show contrast enhancement and features distinctive to neurogenic neoplasms, including a fusiform shape with a “tail sign” (i.e., nerve entering and exiting the mass), a “target sign” (i.e., central hypointense signal surrounded by hyperintense signal on T2 images), a “fascicular sign” (i.e., fascicular nerve bundles seen as small, round intermediate signal structures surrounded by higher signal intensity on T2 images), or a “split-fat sign” (i.e., rind of fat, often best seen over the proximal and distal poles of the mass on long-axis images).

With schwannomas (unlike neurofibromas) arising from larger nerves, the mass is characteristically seen eccentric to the nerve, which facilitates surgical resection and sparing of the nerve.

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor: Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs) typically affect large nerves and have a strong association with neurofibromatosis type 1 (lifetime prevalence, ~10%).

Although MPSNSTs can be difficult to differentiate from BPNSTs (particularly plexiform neurofibromas in patients with neurofibromatosis), the three MRI findings most associated with MPNSTs include large size (>5 cm), infiltrative margins (associated with perilesional edema and perilesional enhancement) and heterogeneous signal on T1, T2, and postcontrast images (due to intratumoral necrosis and bleeding).

Vascular derangement: Vascular derangements can include aneurysm, pseudoaneurysm, thrombosis, and venous varicosity.

True aneurysms involve all layers of the vessel wall (intima, media, and adventitia), and occur most commonly in older men with atherosclerosis or hypertension. Popliteal aneurysms are the most common type of peripheral artery aneurysm (70%), bilateral in at least 50% of patients, and typically undergo repair when >1.5 to 2 cm.

Pseudoaneurysms (also referred to as false aneurysms) occur when a blood vessel wall is injured (e.g., with surgery or an adjacent osteochondroma), and the leaking blood collects in the perivascular soft tissue (often contained by the media or adventitia). These lesions arise from the popliteal artery and may contain lamellated thrombus with areas of high-T1 signal (due to methemoglobin) and low-T2 signal (due to hemosiderin or flow void).

Diagnosis

Schwannoma (BPNST) of the common peroneal nerve.

Pearls

A neurogenic neoplasm should be considered when a fusiform mass is observed in the distribution of a nerve, especially when long-axis images show a “tail” of the mass entering proximally and exiting distally.

Compared to most solitary BPNSTs, MPNSTs are highly associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 and are characterized by large size, perilesional edema, and intratumoral necrosis.

Like neurogenic tumors, popliteal vessel derangements occur in the intermuscular fat plane and have longitudinally-oriented, tail-like structures emanating from the proximal and distal poles of the lesion.

Suggested Readings

- 320 Ahlawat S, Fayad LM. Imaging cellularity in benign and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: utility of the “target sign” by diffusion weighted imaging.. Eur J Radiol 2018; 102: 195-201 PubMed 29685535

- 321 Baptista E, Kubo R, Santos DC, Taneja AK. A teenager presenting with pain and popliteal mass. Pseudoaneurysm of the popliteal artery secondary to a distal femoral osteochondroma.. Skeletal Radiol 2017; 46 (6) 805-806, 841–842 PubMed 28191594

- 322 Leake AE, Segal MA, Chaer RA et al. Meta-analysis of open and endovascular repair of popliteal artery aneurysms.. J Vasc Surg 2017; 65 (1) 246-256.e2 PubMed 28010863

- 323 Matsumine A, Kusuzaki K, Nakamura T et al. Differentiation between neurofibromas and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors in neurofibromatosis 1 evaluated by MRI.. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2009; 135 (7) 891-900 PubMed 19101731

- 324 Miettinen MM, Antonescu CR, Fletcher CDM et al. Histopathologic evaluation of atypical neurofibromatous tumors and their transformation into malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor in patients with neurofibromatosis 1-a consensus overview.. Hum Pathol 2017; 67: 1-10 PubMed 28551330

- 325 Yu YH, Wu JT, Ye J, Chen MX. Radiological findings of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor: reports of six cases and review of literature.. World J Surg Oncol 2016; 14: 142 PubMed 27159980

Case 94

Clinical History

A 59-year-old woman with a lump anterior to the elbow for 1 year. The patient reports the lump is “soft in morning, but it increases in size and firmness by the end of the day” (Fig. 94‑1).

Key Finding

Complex fluid collection in the bicipitoradial bursa.

Top 3 Differential Diagnoses

Bicipitoradial bursitis: The bicipitoradial bursa is located between the biceps tendon and the radial tuberosity. The role of this synovial-lined bursa is to reduce friction between the tendon and bone during pronation and supination.

Bursal inflammation and enlargement may occur secondary to numerous etiologies. The most common cause is chronic mechanical friction in association with biceps tendinopathy or partial tearing. Less common etiologies include synovial-based inflammatory processes (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis), indolent infection (e.g., tuberculosis), neoplastic conditions (e.g., synovial chondromatosis), and metabolic disorders (e.g. tumoral calcinosis). Patients sometimes notice that non-neoplastic fluid collections (e.g., bursitis, cysts) wax and wane in size.

Periarticular cyst: A periarticular cyst (or ganglion) may arise from the elbow, most commonly at the anterior aspect of the radiocapitellar joint. Such cysts are often identified at the elbow joint line proximal to the arcade of Frohse (proximal edge of the supinator muscle), with a thin pedicle that allows a confident diagnosis.

Cysts can exert mass effect on the radial nerve or its branches, most often the superficial (sensory) branch of the radial nerve, compressing it against the extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle, with clinical symptoms that may mimic lateral epicondylitis. When the deep (motor) branch of the radial nerve (posterior interosseous nerve) is affected, symptoms are related to weakness in the extensor muscles, and MRI can show denervation changes in the affected muscles.

Hematoma: Blood may collect in the antecubital region after tissue trauma. In the acute setting, such blood may be related to common injuries (e.g., biceps tendon rupture) or uncommon injuries (e.g., brachialis muscle rupture with full-thickness anterior capsule tear associated with a transient elbow dislocation). Percutaneous tissue trauma (e.g., iatrogenic or IV drug use) may occasionally be complicated by hematoma and/or infection.

After an elbow dislocation event, characteristic concomitant injuries should be sought, including collateral ligament rupture, osseous injury (e.g., coronoid process fracture), and neurovascular injury (e.g., brachial artery occlusion).

Diagnosis

Bicipitoradial bursitis.

Pearls

Non-neoplastic conditions can mimic soft-tissue neoplasms. Knowledge of the characteristic anatomic sites for bursae can be helpful in avoiding misdiagnosis.

Although the bicipitoradial bursa is not normally identified on MRI, it can become inflamed and distended. Bicipitoradial bursitis often presents clinically as a soft-tissue mass, and it may cause compression of the adjacent radial nerve branches.

Unlike a ganglion cyst (which often arises at the anterior aspect of the radiocapitellar joint), bicipitoradial bursitis invariably extends between the biceps tendon and radial tuberosity.

Suggested Readings

- 326 Luokkala T, Temperley D, Basu S, Karjalainen TV, Watts AC. Analysis of magnetic resonance imaging-confirmed soft tissue injury pattern in simple elbow dislocations.. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2019; 28 (2) 341-348 PubMed 30414825

- 327 Rodriguez Miralles J, Natera Cisneros L, Escolà A, Fallone JC, Cots M, Espiga X. Type A ganglion cysts of the radiocapitellar joint may involve compression of the superficial radial nerve.. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2016; 102 (6) 791-794 PubMed 27562829

- 328 Schreiber JJ, Potter HG, Warren RF, Hotchkiss RN, Daluiski A. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in acute elbow dislocation: insight into mechanism.. J Hand Surg Am 2014; 39 (2) 199-205 PubMed 24480682

- 329 Skaf AY, Boutin RD, Dantas RW et al. Bicipitoradial bursitis: MR imaging findings in eight patients and anatomic data from contrast material opacification of bursae followed by routine radiography and MR imaging in cadavers.. Radiology 1999; 212 (1) 111-116 PubMed 10405729

- 330 Yamazaki H, Kato H, Hata Y, Murakami N, Saitoh S. The two locations of ganglions causing radial nerve palsy.. J Hand Surg Eur Vol 2007; 32 (3) 341-345 PubMed 17331627

- 331 Yap SH, Griffith JF, Lee RKL. Imaging bicipitoradial bursitis: a pictorial essay.. Skeletal Radiol 2019; 48 (1) 5-10 PubMed 29797016

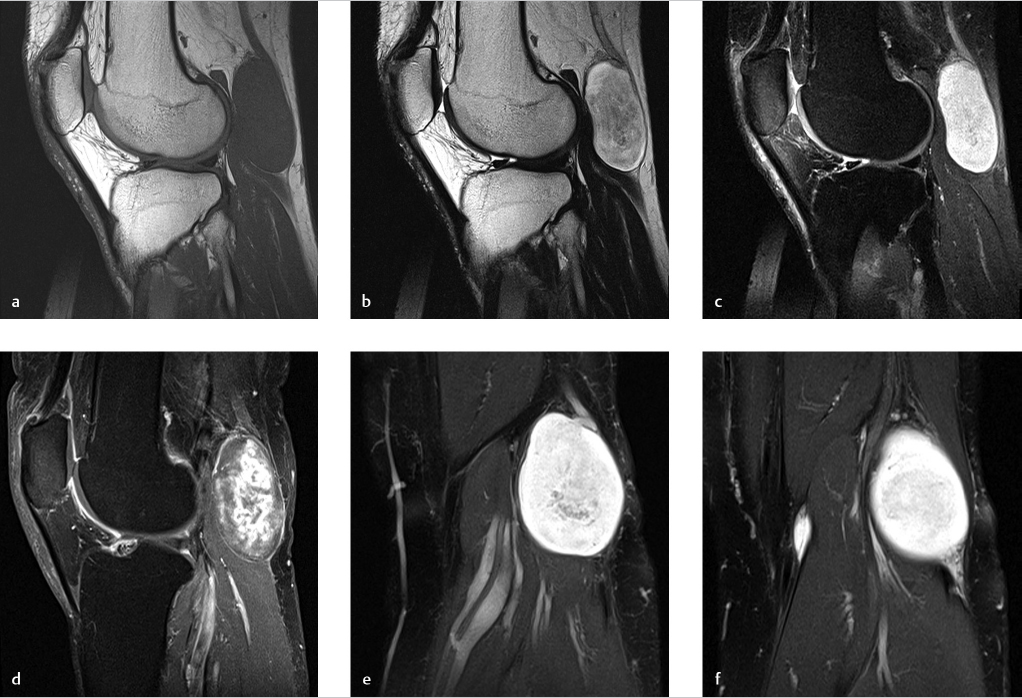

Case 95

Clinical History

A 42-year-old woman with recurrent knee pain and fullness 10 years after arthroscopic synovectomy (Fig. 95‑1).

Key Finding

Infiltrative intra-articular mass of low-T2 signal intensity, with erosions.

Top 3 Differential Diagnoses

Tenosynovial giant cell tumor (TSGCT), diffuse type: Tenosynovial giant cell tumor is a synovial-based proliferative disorder that can target the synovial lining of a joint, tendon sheath, or bursa.

Since revision of nomenclature by the World Health Organization in 2013, the umbrella term TSGCT is used to apply to giant cell-containing neoplasms that were formerly known as “pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS)” and “giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath.” Currently, the favored lexicon for the family of TSGCT lesions describes the tumors by extent as either localized (nodular) or diffuse (infiltrative).

With the diffuse-type of TSGCT, the most common presentation is a monoarticular process in the knee. Any synovial joint can be affected, including the hip, ankle, and elbow. With radiography, the intra-articular soft-tissue mass is characteristically nonmineralized. With MRI, the hallmark is a low-T2 mass infiltrating the joint recesses, with hemosiderin-containing tissue that shows susceptibility (“blooming”) artifact on gradient-echo images and enhancement after contrast administration. With sonography, vascularity can be seen in the mass. These nonmalignant neoplasms can be locally aggressive, with adjacent osseous erosions and recurrence after surgery.

Treatment with surgery alone is associated with recurrence rates of 30 to 40%. Promising results are now reported for surgery combined with a new generation of immune-oncology drugs.

Synovial chondromatosis, primary: Like TSGCT, primary synovial chondromatosis is generally considered a monoarticular process that most commonly presents in young to middle-aged patients and often targets the knee (70%). Secondary synovial chondromatosis is a term that is sometimes used to refer to loose bodies that occur secondary to a chronic arthritis, typically osteoarthritis.

With primary synovial chondromatosis, intra-articular cartilaginous loose bodies are shed into the joint. These nodular fragments are typically small (<1 cm) and relatively similar in size. At the time of presentation, no radiographically visible mineralization (calcification or ossification) is present in one-third of cases. The imaging findings are considered pathognomonic when innumerable mineralized bodies of similar size and shape are observed in a joint with preserved articular cartilage.

Hemophilic arthropathy: Hemophilic arthropathy can result in low-T2 signal with thickening of the synovium and can often affect the knee. Like TSGCT, hemosiderin in the joint “blooms” on gradient-echo MRI, and there is no mineralization on radiographic examinations. Unlike TSGCT and synovial chondromatosis, hemophilic arthropathy is often polyarticular and only affects males.

Diagnosis

Tenosynovial giant cell tumor, diffuse type (pigmented villonodular synovitis).

Pearls

With MRI, hypointense signal on T2 images is generally caused by a lesion containing calcification, hemosiderin, or fibrous tissue. Radiography is helpful in differentiating mineralized versus nonmineralized tissue.

The classic presentation of a diffuse type of TSGCT is an infiltrative soft-tissue mass with T2-hypointense signal, most commonly as a monoarticular process involving the knee joint.

Primary synovial chondromatosis is nonmineralized in one-third of cases. In the remaining cases, the diagnosis can generally be made when innumerable mineralized bodies of similar size and shape are observed in a joint with preserved articular cartilage.

Suggested Readings

- 381 Boutin RD, Bindra J, Canter RJ. Imaging soft tissue tumors. In: Chapman MW, James MA, eds. Chapman’s Comprehensive Orthopaedic Surgery. 4th ed. New Delhi: Jaypee; 2019

- 382 Evenski AJ, Stensby JD, Rosas S, Emory CL. Diagnostic imaging and management of common intra-articular and peri-articular soft tissue tumors and tumor like conditions of the knee.. J Knee Surg 2019; 32 (4) 322-330 PubMed 30449023

- 383 Gounder MM, Thomas DM, Tap WD. Locally aggressive connective tissue tumors.. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36 (2) 202-209 PubMed 29220303

- 384 Papakonstantinou O, Isaac A, Dalili D, Noebauer-Huhmann IM. T2-weighted hypointense tumors and tumor-like lesions.. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 2019; 23 (1) 58-75 PubMed 30699453

- 385 Wadhwa V, Cho G, Moore D, Pezeshk P, Coyner K, Chhabra A. T2 black lesions on routine knee MRI: differential considerations.. Eur Radiol 2016; 26 (7) 2387-2399 PubMed 26420500

Case 96

Clinical History

A 31-year-old patient with negative radiographs and an a traumatic, firm axillary mass. The patient presents with serial MRI examinations for tumor surveillance while on systemic treatment that includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and tyrosine kinase inhibitors (sorafenib) (Fig. 96‑1).

Key Finding

Nonmineralized, soft-tissue mass with an infiltrative border (“tail sign”) that responds favorably to nonoperative treatment.

Top 3 Differential Diagnoses

Desmoid tumor: Desmoid-type fibromatosis is a locally aggressive mesenchymal neoplasm that produces fibrotic tissue and grows with infiltrative margins. Although these are considered intermediate-grade neoplasms and do not metastasize, they can cause significant morbidity because of their infiltrative growth and tendency to recur locally after surgery.

On MRI, desmoid tumors typically contain areas of intermediate and low-T1 signal. As these lesions evolve and respond to treatment, signal intensity tends to progressively decrease on T2 and postcontrast images (reflecting changes from cellular neoplasm to collagenous scar). Favorable treatment response is also shown by progressive decrease in tumor volume over time. Characteristic band-like linear extension along a fascial plane (“tail sign”) at the tumor margin is seen in approximately 80% of cases. Intralesional necrosis is generally absent (unlike many sarcomas).

The three most common extra-abdominal locations for desmoid-type fibromatosis are the extremities (60%), paraspinal/chest wall region (25%), and head/neck (15%). The compartment of origin and local extent (e.g., involvement of crucial structures, neurovascular bundles, bones) are the prime determinants of treatment and prognosis. Multicentric lesions occur in a small minority of patients (~10%); this is classically associated with familial adenomatous polyposis and the diagnosis commonly referred to as Gardner syndrome.

Treatment is tailored to the individual patient. First-line therapy generally favors close observation and systemic treatment (e.g., NSAIDs, hormonal blockade, cytotoxic chemotherapy, tyrosine-kinase inhibitors), rather than surgery or radiation therapy.

Tenosynovial giant cell tumor: When radiographs do not show any mineralization, the MRI differential diagnosis of a hypointense mass with an infiltrative margin most commonly includes tenosynovial giant cell tumor. Tenosynovial giant cell tumors are classically observed along a tendon sheath (“giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath”) or in a synovial joint (“pigmented villonodular synovitis”).

Miscellaneous fibrous soft-tissue tumors: With negative radiographs, uncommon miscellaneous fibrous tumors can be in the differential diagnosis of a hypointense mass with an infiltrative margin. These fibrous (fibroblastic or myofibroblastic) tumors include fascia-based lesions, particularly nodular fasciitis, desmoplastic fibroma, and fibrosarcoma.

Diagnosis

Desmoid tumor (aggressive fibromatosis).

Pearls

Imaging has a crucial role in the diagnosis, local staging, and management of desmoid-type fibromatosis.

Management of desmoid-type fibromatosis often begins with systemic treatment, rather than surgery or radiation.

Favorable response to systemic treatment is shown by decreased volume and decreased signal intensity on serial MRI examinations.

Suggested Readings

- 337 Benech N, Walter T, Saurin JC. Desmoid tumors and celecoxib with sorafenib.. N Engl J Med 2017; 376 (26) 2595-2597 PubMed 28657872

- 338 Braschi-Amirfarzan M, Keraliya AR, Krajewski KM et al. Role of imaging in management of desmoid-type fibromatosis: a primer for radiologists.. Radiographics 2016; 36 (3) 767-782 PubMed 27163593

- 339 Gounder MM, Mahoney MR, Van Tine BA et al. Sorafenib for advanced and refractory desmoid tumors.. N Engl J Med 2018; 379 (25) 2417-2428 PubMed 30575484

- 340 Park JS, Nakache YP, Katz J et al. Conservative management of desmoid tumors is safe and effective.. J Surg Res 2016; 205 (1) 115-120 PubMed 27621007

- 341 Sheth PJ, Del Moral S, Wilky BA et al. Desmoid fibromatosis: MRI features of response to systemic therapy.. Skeletal Radiol 2016; 45 (10) 1365-1373 PubMed 27502790

- 342 Turner B, Alghamdi M, Henning JW et al. Surgical excision versus observation as initial management of desmoid tumors: a population based study.. Eur J Surg Oncol 2019; 45 (4) 699-703 PubMed 30420189

Case 97

Clinical History

A 39-year-old man with a history of a motor vehicle accident complaining of decreased cutaneous sensation and a mass lateral to the right hip (Fig. 97‑1).

Key Finding

Posttraumatic fluid-like collection in the deep subcutaneous tissue along the superficial aspect of the fascia.

Top 3 Differential Diagnoses

Morel–Lavallee lesion: Morel–Lavallee lesions are the result of trauma with shearing forces superficial to the fascia. With such internal degloving injuries, a hemolymphatic collection is formed, most commonly in the back/flank, hip/thigh, and knee regions (classically located lateral to the greater trochanter of the hip).

Imaging features evolve over time, as expected, with collections containing variable amounts of blood products and lymphatic fluid, often with globules of fat. Acute/subacute collections tend to appear more heterogeneous and have ill-defined margins with perilesional edema (resembling hematomas). Chronic collections become more homogeneous and often develop a fibrous pseudocapsule. Regardless of the age of the Morel–Lavallee lesion, they have an ovoid or fusiform shape, and do not have internal vascularity.

Bursitis: Collections that appear fluid-like can occur superficial to the fascia in bursae. In the hip region, for example, there are numerous bursae that may be affected by inflammation/infection and repetitive microtrauma. This is seen most often in the setting of tendinopathy with peritendinitis in patients with greater trochanteric pain syndrome. Superimposed imaging findings of edema and fluid also are commonly observed immediately after percutaneous injections (e.g., corticosteroid injection).

Infections involving the greater trochanteric bursa region are rare in the absence of overlying skin disruption (e.g., ulceration). In developing countries, however, massive trochanteric bursal fluid distension is a well-recognized complication of indolent infection with mycobacteria (e.g., tuberculosis).

Neoplasm: Soft-tissue neoplasms can be in the differential diagnosis of a mass lesion located superficial to the fascia. The most common neoplasms associated with the fascia are nodular fasciitis (most commonly in the upper extremities of young adults) and fibromatosis.

Neoplasms have vascularity and abnormal enhancement after contrast administration. Sarcomas are located most commonly deep to the fascia, but superficial neoplasms can occur. Sarcomas often appear heterogeneous, with areas of intralesional necrosis.

Diagnosis

Morel–Lavallee lesion.

Pearls

A wide variety of hemorrhagic, inflammatory, and neoplastic lesions can occur in the deep subcutaneous soft tissue abutting the fascia.

A Morel–Lavallee lesion is a posttraumatic, fluid-like collection in the deep subcutaneous tissue along the superficial aspect of the fascia. The imaging appearance evolves according to the age of the injury.

The imaging appearance of a Morel–Lavallee lesion is essentially pathognomonic when a characteristic appearance is observed in a classic location after high-energy trauma.

Suggested Readings

- 343 De Coninck T, Vanhoenacker F, Verstraete K. Imaging features of Morel-Lavallée lesions.. J Belg Soc Radiol 2017; 101 (Suppl. Suppl 2) 15 PubMed 30498807

- 344 Kirchgesner T, Tamigneaux C, Acid S et al. Fasciae of the musculoskeletal system: MRI findings in trauma, infection and neoplastic diseases.. Insights Imaging 2019; 10 (1) 47 PubMed 31001705

- 345 McKenzie GA, Niederhauser BD, Collins MS, Howe BM. CT characteristics of Morel-Lavallée lesions: an under-recognized but significant finding in acute trauma imaging.. Skeletal Radiol 2016; 45 (8) 1053-1060 PubMed 27098352

- 346 McLean K, Popovic S. Morel-Lavallée lesion: AIRP best cases in radiologic-pathologic correlation.. Radiographics 2017; 37 (1) 190-196 PubMed 28076017

- 347 Nickerson TP, Zielinski MD, Jenkins DH, Schiller HJ. The Mayo Clinic experience with Morel-Lavallée lesions: establishment of a practice management guideline.. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2014; 76 (2) 493-497 PubMed 24458056

- 348 Spain JA, Rheinboldt M, Parrish D, Rinker E. Morel-Lavallée injuries: a multimodality approach to imaging characteristics.. Acad Radiol 2017; 24 (2) 220-225 PubMed 28087046

Case 98

Clinical History

A 65-year-old morbidly obese woman with hypothyroidism and a chronically enlarging mass at the medial thigh region. “Solitary mass, without pain. Evaluate panniculus versus hernia versus neoplasm” (Fig. 98‑1).

Key Finding

Large, pendulous mass at the inner thigh in a morbidly obese patient.

Top 3 Differential Diagnoses

Massive localized lymphedema: Massive localized lymphedema is an area of hypertrophic superficial soft tissue secondary to chronic obesity-induced lymphedema. In morbidly obese patients, progressive deposition of subcutaneous fat and retarded lymph drainage can result in gigantic pseudoneoplastic lesions, especially in areas of loose skin at the inner thigh, groin, and lower abdominal regions.

On clinical examination, massive localized lymphedema may initially be confused with more common findings of a large panniculus, hernia, or neoplasm. Massive localized lymphedema, unlike typical lymphedema, is more localized and cannot be reversed by conservative management (e.g., compression stockings). Treatment focuses on surgical resection of the overgrown tissue, in addition to weight loss. If untreated, massive localized lymphedema may progress to angiosarcoma (~10% of cases; see below).

On histologic evaluation of these masses, there is lymphatic proliferation with lymhangiectasia, thickening of fibrous connective tissue bands, and edema with capillary vascular proliferation. There are characteristically fibroblasts, but no lipoblasts that would be seen in a liposarcoma.

Well-differentiated liposarcoma: Well-differentiated liposarcoma, also known as atypical lipoma, occurs much more commonly in the deep (subfascial) soft tissues than the superficial (subcutaneous) fat layer. In both locations, these lesions typically have well-defined margins that sharply demarcate the mass from the surrounding tissue; edema is not a prominent feature. With these lipomatous tumors, histology samples are positive for MDM2 gene amplification.

Angiosarcoma: Angiosarcoma is a rare neoplasm (< 2% of soft-tissue sarcomas) that generally has poor prognosis. Important risk factors are prior radiation therapy and chronic lymphedema, generally with a latency period of over 5 years. In patients with risk factors, angiosarcoma may be considered in the presence of a vascular tumor with an aggressive, infiltrative appearance (e.g., fungating mass in the subcutaneous fat with a background of diffuse lymphedema).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree