Patellar Tendon Rupture

Ami V. Vakharia

Daniel B. Nissman

FINDINGS

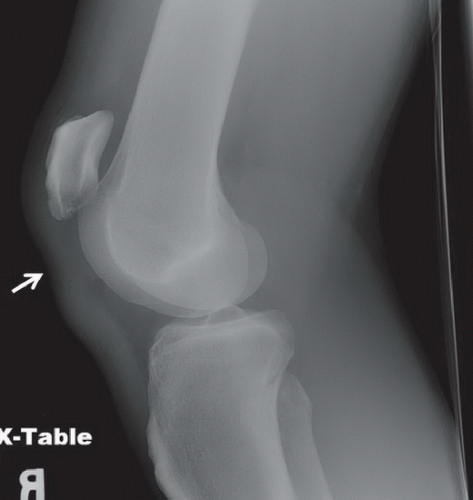

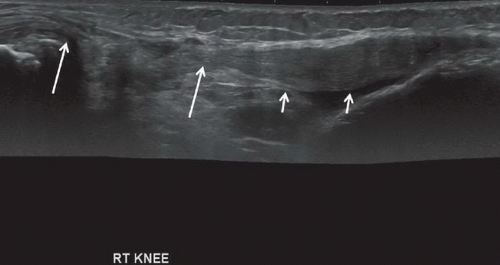

Lateral radiograph of the right knee (Fig. 96A) demonstrates patella alta and focal deficiency (arrow) in the proximal patellar tendon; distal patellar tendon is somewhat wavy. Long-axis gray-scale sonographic image of the right knee (Fig. 96B) demonstrates complete loss of continuity of the normal fibrillar echotexture of the proximal patellar tendon. Long arrows depict the tear edges. Short arrows depict intact tendon, which appears somewhat thickened and wavy because of loss of normal tensile stress; an element of tendinosis may also be present.

DIAGNOSIS

Patellar tendon rupture.

DISCUSSION

Acute injuries of the knee extensor mechanism composed of the quadriceps tendon, the patella, and the patellar tendon most commonly result in patellar fracture followed in incidence by quadriceps tendon rupture; patellar tendon rupture is the least common of these extensor mechanism injuries. Patellar tendon rupture occurs most often in physically active men under the age of 40, but may also occur in older patients with underlying systemic disease. The

proximal patellar tendon is injured with sports injuries, and other sites (midsubstance or distal tendon) are usually torn with underlying medical conditions. The normal patellar tendon is able to withstand extremely large tensile stresses, the equivalent of 17.5 times normal body weight.1 As a result, a preexisting pathologic condition is necessary before rupture can occur. Most commonly, this condition is patellar tendinosis, a lesion resulting from repetitive microtrauma. Systemic conditions such as gout, rheumatoid arthritis, renal failure, diabetes mellitus, systemic lupus erythematosus, and medication (corticosteroids and fluoroquinolones) have also been implicated in patellar tendon rupture.

proximal patellar tendon is injured with sports injuries, and other sites (midsubstance or distal tendon) are usually torn with underlying medical conditions. The normal patellar tendon is able to withstand extremely large tensile stresses, the equivalent of 17.5 times normal body weight.1 As a result, a preexisting pathologic condition is necessary before rupture can occur. Most commonly, this condition is patellar tendinosis, a lesion resulting from repetitive microtrauma. Systemic conditions such as gout, rheumatoid arthritis, renal failure, diabetes mellitus, systemic lupus erythematosus, and medication (corticosteroids and fluoroquinolones) have also been implicated in patellar tendon rupture.

The typical mechanism of injury is a forceful contraction of the quadriceps muscle in the setting of a flexed knee, a situation that may arise with an abrupt deceleration while running or jumping. In the elderly, a common mechanism is a fall on a flexed knee. Signs and symptoms include highriding patella, swelling, tenderness, cramping, and complete inability to extend the knee.

Although physical examination is usually sufficient to diagnose a patellar tendon rupture, confirmation with imaging is sometimes necessary. Regardless of imaging modality, the patellar and quadriceps tendons are taut when the knee is imaged in any degree of flexion and have well-defined anterior and posterior margins; any deviation is concerning for tendon pathology. The patellar tendon itself demonstrates homogenous soft tissue density on radiographs that is visible because it is bordered by fat density both anteriorly and posteriorly, homogeneous low signal on both T1- and T2-weighted MR images, and a fibrillar echotexture along the long axis of the tendon on ultrasonography. Waviness of either the patellar or quadriceps tendon is concerning for a tear. A lateral radiograph is usually sufficient to confirm the diagnosis of a patellar tendon rupture especially when proximal displacement of the patella (patella alta), redundant quadriceps tendon, and focal attenuation of the patellar tendon are seen. A partial tear or tendinosis is more likely if either the anterior or posterior (most common) interface is blurred or there is focal enlargement without patella alta; radiographs are unable to make this distinction. MRI and ultrasonography are equally capable of diagnosing and characterizing patellar tendon ruptures. Sagittal fluid-sensitive images (MRI) or long-axis images (ultrasonography) through the patellar tendon are usually sufficient for diagnosis of a tear. A fullthickness tear will often, but not always, have a clearly definable gap between the torn ends of the tendon. Axial or short-axis images may be needed to assess the size of a partial tear. Signs of a tear include a transverse full-thickness or partial-thickness, fluid-filled defect. On MRI, this fluidfilled defect will be a fluid bright cleft in an otherwise intermediate-to dark-appearing tendon. Sonographically, patellar tendon tears may appear as nearly anechoic clefts (fluid) or heterogeneously hyperechoic material (interposed fat from Hoffa’s fat pad) displaced into the tear. The quadriceps tendon may be redundant because of lack of tensile stress. In cases where there is uncertainty regarding the extent of the tear, dynamic sonography can be performed to document the presence of tear enlargement with either attempted active knee extension or passive knee flexion. As most tears occur in the presence of tendinosis, thickening of the tendon and elevated, but not fluid bright, signal will likely be seen adjacent to the tear on MRI, and thickened, hypoechoic tendon demonstrating loss of the normal fibrillar echotexture will be noted on ultrasonography.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree