KEY WORDS

Adrenal Hemorrhage. Hemorrhage into the adrenal gland is a common cause of a neonatal abdominal mass. It resolves spontaneously, often with development of calcifications.

Beckwith-Wiedemann Syndrome. Congenital malformation characterized by hemihypertrophy (overgrowth of one side of the body), enlargement of the tongue, and omphalocele (protuberance of bowel through a defect in the abdominal wall).

Choledochal Cyst. Congenital dilatation of the biliary tree. Clinical findings include jaundice, abdominal mass, and pain.

Enteric Duplication. Congenital duplication of the bowel. The involved segment does not communicate with the remainder of the bowel and presents as a fluid-filled mass.

Hemangioendothelioma. Benign tumor of the liver. Affects neonates and infants under the age of 6 months. Patients usually present with heart failure and a large liver.

Hematocolpos. Blood in a dilated vagina. Vaginal dilatation may be secondary to distal atresia, a septum, or a membrane. Patients present with a midline pelvic mass. Has been associated with uterine duplication anomalies.

Hepatoblastoma. Most common hepatic malignancy. Occurs in young children, usually under the age of 3 years.

Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Rare malignancy of the liver in older children and adolescents.

Hydronephrosis. Dilatation of the renal pelvis and calyces. Most common cause is obstruction at the level of the renal pelvis. Usually found in neonates and infants.

Infant. Individual between 1 month and 2 years of age.

Intussusception. Obstructed bowel coiled on itself. Seen in young children.

Lymphoma. Malignancy of lymphoid tissue. The non-Hodgkin form of lymphoma is most common in the abdomen. Usually involves bowel and lymph nodes, but it can involve the liver, spleen, and kidneys.

Mesenchymal Hamartoma. Rare benign liver mass. Most commonly seen in children under 2 years of age.

Meningocele. Cystic dilatation of the spinal canal at the site of a bony defect. May appear as a pelvic mass in the neonate when it protrudes anterior to the sacrum.

Mesentery. A fan-shaped fold of peritoneum that connects the small bowel and colon to the posterior abdominal wall.

Mesenteric Cyst. Cyst filled with lymph. Found in the mesentery and presents as an asymptomatic abdominal mass.

Mesoblastic Nephroma. Rare benign renal tumor occurring in neonates and young infants. Rarely metastasizes. Treated by nephrectomy.

Multicystic Dysplastic Kidney. Unilateral renal cystic disease. It develops in utero and is the result of atresia of the renal pelvis and ureter. Renal tissue is nonfunctioning.

Multilocular Cystic Nephroma. Nonhereditary, benign renal mass. Affect patients under 4 years of age. Treatment is nephrectomy.

Neonate. Infant under 1 month of age.

Nephroblastomatosis. Persistence of fetal renal tissue in the kidneys. Has been associated with Wilms tumor. Usually found in neonates and infants. Treatment is chemotherapy.

Neuroblastoma. Second most common abdominal mass after Wilms tumor. Usually arises in the adrenal gland, but it may arise in ganglia (nervous tissue) along the spine. Occurs between birth and 5 years of age. Most patients present with palpable abdominal masses.

Omentum. A fold that joins the stomach to the liver or colon. Cysts may develop in the omentum and may cause an abdominal mass.

Posterior Urethral Valves. Most common cause of urethral obstruction in male infants and children. Does not affect females.

Pyloric Stenosis. The pylorus (the exit of the stomach) is narrowed and the wall is thickened. A cause of projectile vomiting in infants.

Renal Vein Thrombosis. Usually the result of dehydration. Also seen in infants of diabetic mothers. Classic clinical findings are a flank mass and hematuria (blood in urine).

Rhabdomyosarcoma. Malignant muscle tumor that occurs in childhood and has a particular affinity for the bladder, vagina, and prostate.

Teratoma. Usually benign mass composed of elements of most tissues in the body, notably skin, hair, bone, and teeth. Most commonly found in the sacrococcygeal area in neonates and ovary in adolescent girls. Malignancy occurs in less than 10%.

Ureterocele. Dilatation of the distal ureter where it inserts into the bladder. Most often associated with a duplicated kidney.

Ureteropelvic Junction Obstruction. Most common congenital cause of renal obstruction. Results from a block of the upper end of the ureter just below the renal pelvis. Usually found in neonates.

Wilms Tumor. Most common renal malignancy in childhood. Usually affects children between 1 and 6 years of age. Associated with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (mentioned previously in this section) and hemihypertrophy. Treatment is chemotherapy and surgical resection.

The Clinical Problem

The differential diagnosis of pediatric abdominal masses varies based on patient age (neonate vs. infant and older child) and the presence or absence of symptoms.

Sonography is used to confirm the presence of the mass and to suggest its size and position. Most, if not all, masses will require additional imaging studies, and the type of study can be influenced by the sonographic findings. For example, if sonography demonstrates hydronephrosis, a nuclear medicine study is performed to assess renal function, and a contrast examination of the bladder (cystogram) is obtained to determine if reflux is causing the hydronephrosis. If sonography demonstrates a benign cystic mass, further imaging is often not indicated. If sonography reveals a solid abdominal mass, however, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging is performed to define the extent of disease.

NEONATAL ABDOMINAL MASSES

Renal masses account for the majority (>70%) of abdominal masses in neonates and virtually all are asymptomatic. These masses come to clinical attention because they produce a palpable abdominal mass. The common renal masses are hydronephrosis and multicystic dysplastic kidney. Rarer renal masses include autosomal recessive polycystic disease, mesoblastic nephroma, renal vein thrombosis, and nephroblastomatosis.

Less often, abdominal masses in neonates arise in the adrenal glands (usually adrenal hemorrhage or neuroblastoma), the reproductive organs (ovarian cysts and hydrocolpos), liver (hemangioendothelioma), biliary tract (choledochal cyst), gastrointestinal tract (duplication and mesenteric cysts), or in the sacrococcygeal area (teratoma).

ABDOMINAL MASSES IN THE OLDER INFANT AND CHILD

In older infants (after 2 months of age) and children, most abdominal masses are of renal origin and most are detected as asymptomatic, palpable masses. Wilms tumor, which arises in the kidney, and neuroblastoma, which arises in the adrenal gland, are the most common abdominal masses. Ovarian tumors (teratomas), rhabdomyosarcoma, hepatic tumors (hepatoblastoma and hepatoma), and gastrointestinal tumors (lymphoma) may also occur in this age group. Occasionally, abdominal masses in this age group will produce symptoms. These include pyloric stenosis, intussusception, appendiceal abscess, and ovarian torsion. This chapter will first review the common asymptomatic masses in older infants and children, followed by a discussion of symptomatic masses in young infants (e.g., pyloric stenosis and intussusception). Symptomatic masses that occur in both pediatric and adult populations are discussed elsewhere in this textbook.

Technique

TRANSDUCERS

Sector-type or curved array probes are used for imaging most abdominal masses. A linear array transducer may improve visualization of bowel morphology and abnormalities in the near field. Abdominal sonograms are performed with the highest frequency transducer possible. A 5-MHz transducer usually suffices in children and thin adolescents, and a 3.5-MHz transducer may be needed in larger adolescents. A 7.5-MHz transducer is usually adequate in small infants.

SCANNING TECHNIQUES

Kidneys and adrenal glands are examined in transverse and longitudinal planes. The right kidney and adrenal gland are seen best with the patient in the supine or left lateral decubitus position, using the right hepatic lobe as an acoustic window. The left kidney and adrenal gland are imaged with the patient in the supine or the right lateral decubitus position, using the spleen as an acoustic window. Scanning the patient in the prone position may be advantageous when abundant bowel gas obscures visualization using an anterior approach. Images of the kidneys are obtained through the upper poles, midsection, and lower poles. Renal lengths are noted. Images of the urinary bladder are obtained as part of the routine renal sonogram. Always check the bladder first, and take a picture before it empties.

Although adrenal sonograms are rarely requested in adults, it is not uncommon to follow adrenal hemorrhage in neonates with ultrasound. The right adrenal is easily seen through the liver at a level just superior to the upper pole of the kidney. It lies medial to the right lobe of the liver, behind the inferior vena cava (IVC), and above the upper pole of the right kidney. The left adrenal lies lateral to the aorta, medial to the spleen and upper pole of the left kidney, and posterior to the pancreatic tail. The left adrenal gland is often best seen with the infant either supine or left side up. It helps to use a posterior approach to demonstrate the left adrenal gland. The adrenal glands can be recognized by their “V” or “Y” shape on longitudinal views and by their linear, “V,”“Y,” or “L” configuration on transverse views.

The liver is evaluated in both longitudinal and transverse scans with the patient in the supine position. Examining the patient in the left posterior oblique position may be helpful to evaluate the deeper posterior parts of the right lobe. Most of the liver can be imaged by a subcostal approach, although an intercostal approach with a sector transducer may be necessary for evaluating the superior parts of the liver, especially the subdiaphragmatic part of the right lobe. The use of pulsed and color flow Doppler imaging can help to differentiate blood vessels from bile ducts and can characterize vascular abnormalities. The gallbladder, spleen, and pancreas are examined as part of a routine liver sonogram.

The bowel is examined in longitudinal and transverse planes. Firm pressure is applied with a linear array transducer in order to displace normal air-filled bowel loops out of the field of view.

The peritoneal cavity is examined for ascites or tumor. The examination should include the subdiaphragmatic spaces, the space between the right kidney and liver (Morison’s pouch), the paracolic gutters, and the cul-de-sac.

Pelvic sonography in children is usually performed transabdominally with a distended bladder. Adequate bladder distention can be achieved either by having the patient drink large volumes of fluid, or if the patient is not allowed oral intake, the bladder can be distended with sterile fluid through a Foley catheter. Endovaginal scanning is not used in younger children, although this approach can be useful in adolescent females when findings with the transabdominal approach are equivocal. Scans of the ovaries and uterus are obtained in both the sagittal and transverse planes. In some instances, placing the patient in a decubitus position and scanning directly over the adnexa will improve visualization of the ovaries. The use of tissue harmonics can improve organ visualization and image quality. Measurements of the ovaries and uterus are obtained in three orthogonal planes.

As the well-known adage states, “Children are not just small adults,” the following tips may prove useful when scanning the pediatric patient.

SONOGRAPHER’S APPROACH TO CHILDREN

1. Start the examination in a well-lit room.

2. Do not wear a white coat.

3. Maintain steady eye contact, and concentrate on the child rather than the parents.

4. Speak with a soft voice.

5. Do not talk about sonographic findings in front of the child, although some children respond well to having their anatomy discussed. If you discuss the sonogram findings, use simple terms. For instance, “This long tube is a vessel. It has blood in it.”

6. Allow the child to become familiar with the room and the system.

7. Unless contraindicated, feed small infants during the study.

8. Have the parents help hold the child. Use warm gel. Let the child put the gel on him or herself.

9. Young children may cooperate more by telling them that they are going to be on TV.

10. Show small children something dynamic on ultrasound (e.g., the beating heart) to interest them in the procedure.

IMMOBILIZATION

Infants and young children can usually be examined by having an adult, preferably a parent, restrain the shoulders and legs so that the patient falls asleep or at least lies quietly. Sandbags may help to keep infants in a desired position. Always try to distract the older patient with casual conversation about their favorite food or television show.

Older children should be shown the transducer and equipment before you perform the examination so that they will not feel threatened by the assessment. Encouraging the child to feel the transducer or switch on instrumentation to see himself or herself on TV is helpful.

When explanations, reassurance, and restraint on the examination table fail, you may try having the patient sit or lie on the parent’s lap.

SEDATION

Sedation may rarely be necessary in examining uncooperative infants or children. The drugs used for sedation should be individualized for each patient and approved by the anesthesia department for each hospital.

KEEPING THE NEONATE WARM

The neonate must be kept warm. A blanket usually suffices and can also be used to restrain the patient. Small infants should be uncovered for the shortest time possible.

TRANSDUCER CONTACT

The transducer of choice should be the one with the highest frequency and the smallest footprint adequate to the task. In a neonate, this may mean using a small parts transducer. The right upper quadrant may be better visualized by angling up under the costal margin. Use warm gel to ensure good contact and patient cooperation.

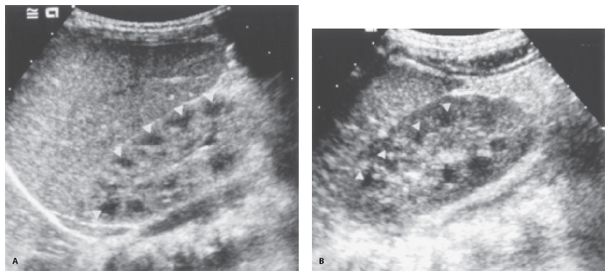

Figure 35-1. ![]() Normal renal anatomy. A. Neonate. Note that the echogenicity of the cortex is equal to that of the liver. The pyramids (arrowheads) are prominent, and there is a paucity of central renal sinus echogenicity. B. Older child (3 years of age). The renal cortex is hypoechoic to liver. The renal pyramids (arrowheads) are less prominent. There is still a paucity of central sinus echogenicity.

Normal renal anatomy. A. Neonate. Note that the echogenicity of the cortex is equal to that of the liver. The pyramids (arrowheads) are prominent, and there is a paucity of central renal sinus echogenicity. B. Older child (3 years of age). The renal cortex is hypoechoic to liver. The renal pyramids (arrowheads) are less prominent. There is still a paucity of central sinus echogenicity.

Normal Anatomy

KIDNEYS

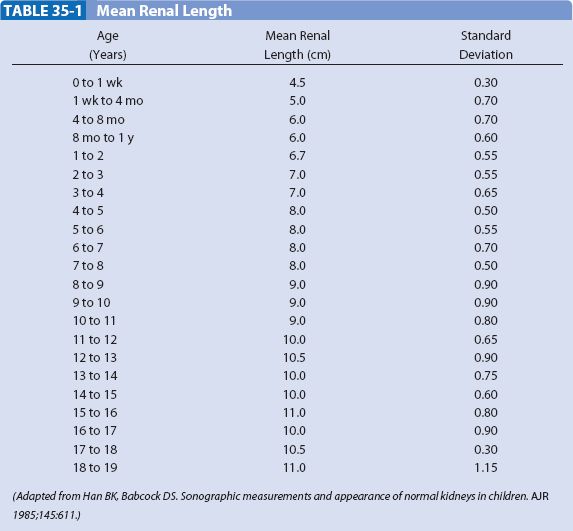

The neonatal kidney demonstrates three unique features (Fig. 35-1). The renal cortex is iso- or hyperechoic to liver or spleen. The renal pyramids are prominent, and there is a paucity of renal sinus echogenicity. The cortex usually becomes hypoechoic relative to liver or spleen by the end of the first year of life, and the pyramids become less well defined by the second or third year of life. The echogenicity of the renal pelvis increases at the end of the first decade of life. Doppler interrogation of the renal artery shows continuous forward flow in diastole, indicating low vascular resistance. Renal size is described by measurements of length (Table 35-1).

ADRENAL GLANDS

Normal adrenal glands are relatively large and easily seen in the neonate because the cortex is prominent. The length of each adrenal gland is between 0.9 and 3.6 cm (mean, 1.5 to 1.7 cm), and the thickness ranges between 0.2 and 0.5 cm (mean, 0.3 cm). The adrenal cortex is hypoechoic to the medulla (Fig. 35-2). Although the adrenal glands become more difficult to visualize after the first few months of life because the cortex atrophies, they often can be seen in older infants and children with the use of high-resolution sonography.

LIVER AND SPLEEN

The liver and spleen in neonates are isoechoic or hypoechoic relative to the kidneys. They become hyperechoic to the kidneys at the end of the first year of life (Fig. 35-1). The appearances of the fissures, ligaments, and vessels are similar to those seen in adults. The intrahepatic and common bile ducts should be visualized. Measurements for the common bile duct are <1 mm in neonates and infants under 1 year of age, <2 mm in infants under 2 years of age, <4 mm in children between 2 and 12 years of age, and <5 mm in adolescents.

BOWEL

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree