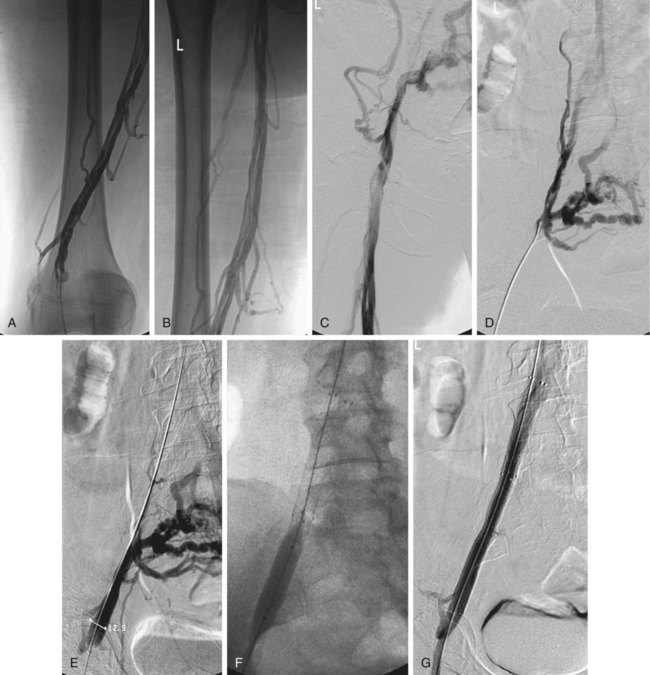

Chronic venous insufficiency (CVI) affects millions of people throughout the United States. The higher venous pressure in the lower extremity veins of patients with CVI results in ambulatory venous hypertension. The majority of cases of CVI are due to past deep venous thrombosis of the iliofemoral segments.1 CVI is a result of a combination of damaged valves leading to reflux and frank venous obstruction.2–6 Acute iliofemoral thrombosis is a common problem that is traditionally treated with conventional systemic anticoagulation (heparin followed by warfarin). Despite anticoagulation, chronic changes of the iliac vein with partial or complete obstruction will occur and lead to postthrombotic syndrome (PTS). During the process of chronic obstruction of the iliac vein, inflammatory changes take place and cause vein wall fibrosis that leads to valve dysfunction, reflux, and CVI.7,8 PTS results in significant morbidity, decreased quality of life, and multiple visits to healthcare providers.9 The symptoms of CVI include ulcerations, chronic pain, and swelling.2 Patients with CVI have traditionally been treated with conservative measures such as medical-grade compression stockings, intermittent compression devices, and wound care in patients with venous stasis ulcers.10–14 Reestablishment of direct antegrade flow through the iliac venous system can alleviate much of the patient’s symptomatology by correcting the obstructive component of CVI.15,16 The remaining reflux component may be addressed by valvular surgery (valvuloplasty, valve transplantation) or percutaneous valve insertion.14,17,18 All patients should have their venous system imaged to determine the adequacy of inflow and outflow. These patients require an initial duplex ultrasound examination of the lower extremity veins to evaluate the patency of venous segments (tibial, popliteal, femoral, and common femoral veins). The pelvic veins and inferior vena cava (IVC) (outflow) are difficult to evaluate with ultrasound, so patients should also undergo either magnetic resonance or computed tomographic venography (MRV, CTV) of the pelvis and abdomen to determine the length of obstruction and adequacy of outflow. Definitive venography will be performed at the time of the intervention.3,9 Air plethysmography is a practical, noninvasive, and relatively inexpensive test that provides physiologic quantitative information about the lower leg (excluding the foot) regarding CVI and correlates with ambulatory venous pressure (AVP) measurements.19–21 The study is performed with an air chamber that surrounds the lower part of the leg and connects to a pressure transducer and recorder. A baseline reading is obtained with the patient in the supine position and the leg elevated to 45 degrees. The patient is then placed in the upright position with all weight on the contralateral limb until the veins are full of blood. This change is the functional venous volume. The venous filling index (VFI) can be calculated (90% venous volume divided by the time required for filling to 90% of venous volume). The patient then performs the heel-raise maneuver to displace the venous volume; the volume displaced by this maneuver is the ejection volume. The ejection fraction (EF) equals ejection volume divided by venous volume. Multiple (10) heel raises are then performed to reach a residual volume plateau. Residual volume divided by venous volume is the residual volume fraction (RVF). The VFI is a measure of global reflux, EF is a measure of calf muscle pumping function, and RVF is a reflection of AVP.9 • Ultrasound for initial venous access • Micropuncture system for venous access • 6F sheaths (long sheaths may be necessary to provide increased pushability) • 5F angled catheters (standard plus hydrophilic), along with hydrophilic guidewires for initial recanalization of occluded segments • Angioplasty balloons for preliminary dilation of venous segments • 10- to 14-mm nitinol stents (long lengths) to cover the occluded segments Knowledge of the normal anatomy and variations of the venous system in the lower extremity, pelvis, and abdomen is required for a safe and successful intervention. A critical review of the preliminary venous studies (ultrasound, MRI, CT) is necessary to determine whether the patient is a candidate for percutaneous intervention, as well as for procedural planning itself (Fig. 100-1). In the popliteal fossa, the vein is often superficial (closer to the posterior skin surface) to the artery, making access more straightforward.13 Other veins that enter the popliteal vein can also be used for access, including the lesser saphenous vein, soleal vein, and veins draining the gastrocnemius muscle group.22 Contrast venography of the popliteal, femoral, and common femoral segments is performed via the sheath (Fig. 100-2, A-C). If satisfactory, a 5F angled multipurpose catheter is advanced into the common femoral vein. Venography of the iliac segment is then performed (Fig. 100-2, D). Multiple oblique projections will often be required to identify the true course of the occluded iliac venous segment. Because multiple collateral channels will frequently be present, identification of the occluded venous channel is often challenging. Systemic anticoagulation is then initiated.

Percutaneous Management of Chronic Lower Extremity Venous Occlusive Disease

Equipment

Technique

Anatomy and Approach

Technical Aspects

Identification of Venous Access Site

Preliminary Venography