PET and PET-CT of Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma

Hans C. Steinert

Ramon de Juan

Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) is the most common neoplasm of the pleura and is directly linked to asbestos exposure. The major differential diagnosis is metastatic adenocarcinoma. Mesotheliomas arise from the visceral or parietal pleura. Invasion into the chest wall, diaphragm, and mediastinum may occur, and pleural effusions are common. MPMs metastasize to the ipsilateral (60%) or contralateral lung and to hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes. Distant metastases are rare.

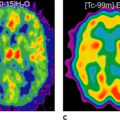

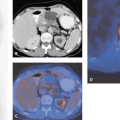

Imaging is particularly helpful in preoperative staging of MPM. Computed tomography (CT) enables early detection of small pleural tumors and pleural effusions. CT demonstrates extension of the tumor along the pleural surfaces and fissures but underestimates tumor chest wall or diaphragmatic invasion and cannot identify pleural fibrosis. MPM avidly takes up fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), but not into fibrosis, and our experience suggests that integrated positron emission tomography (PET)-CT imaging is a promising method for MPM, as the extent of the tumor as well as mediastinal lymph node involvement can be defined precisely.

Introduction

Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) is the most common neoplasm of the pleura, and it is 1,000 times more common in a population exposed to asbestos. MPM usually develops no earlier than 20 to 30 years after asbestos exposure. No correlation to the duration or degree of exposure to asbestos or to smoking history has been found, but the incidence of MPM has been rising and is expected to continue until the year 2020. In western Europe, 250,000 men are expected to die from MPM by 2030 (1). Average survival at diagnosis is similar to that of lung cancer (2).

MPM arises from either the visceral or the parietal pleura. Invasion into the chest wall, diaphragm and mediastinum may occur. Pleural effusions are common and can become large. MPM metastasizes to the ipsilateral (60%) or contralateral lung and to hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes. Distant metastases are rare. Histologically, MPM is divided into an epithelial, a mesenchymal, and a mixed type. The epithelial type is the most common and has the best prognosis (3). The major differential diagnosis is metastatic adenocarcinoma. Immunohistochemical analyses may be required for differentiation.

Staging

The goals of staging are to assess operability and, in patients deemed inoperable, to offer prognostic information. Staging is also important for evaluating patients entering clinical trials and for comparing different studies. The TNM

classification stratifies patients into prognostic categories based on surgical and pathological criteria (e.g., resectability and invasiveness) (4). MPM shows a locoregional growth pattern with direct extension and recurrence within the ipsilateral hemithorax, with increased risk in patients with infiltrated surgical edges or after invasive diagnostic or therapeutic procedures (5). The most frequently affected nodal sites are the mediastinal lymph nodes. Since MPM is primarily a parietal pleural disease, the lymphatic spread pattern is different from that of lung cancer, because N2 rather than N1 nodes may be the first drainage stations (see Table 38.3).

classification stratifies patients into prognostic categories based on surgical and pathological criteria (e.g., resectability and invasiveness) (4). MPM shows a locoregional growth pattern with direct extension and recurrence within the ipsilateral hemithorax, with increased risk in patients with infiltrated surgical edges or after invasive diagnostic or therapeutic procedures (5). The most frequently affected nodal sites are the mediastinal lymph nodes. Since MPM is primarily a parietal pleural disease, the lymphatic spread pattern is different from that of lung cancer, because N2 rather than N1 nodes may be the first drainage stations (see Table 38.3).

Diagnostic imaging in MPM is required on presentation of suspicious clinical features (6,7). Imaging is particularly helpful in preoperative staging of MPM. Computed tomography (CT) enables early detection of small pleural tumors and pleural effusions and definition of the extension of the tumor along the pleural surfaces and fissures. Sheets of tumor can be followed inferiorly along the diaphragmatic crura. However, tumor invasion into the chest wall or diaphragm can be underestimated by CT. With CT, differentiation between tumor and pleural fibrosis is impossible. CT is often not suitable for establishing the diagnosis of MPM, since diffuse pleural thickening may be due to a benign or malignant process.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree