Abstract

Petrous apex abnormalities are usually incidentally detected on imaging for unrelated symptoms. Their deep location precludes direct clinical examination and easy percutaneous biopsy. Therefore, the radiologist plays a key role in the workup of patients with a petrous apex abnormality and needs to be familiar with the anatomy, anatomic variations, and imaging appearance of different disease entities that affect the petrous apex to make the correct diagnosis with a high degree of confidence.

Keywords

Cholesterol granuloma, Endolymphatic sinus tumor, Petrous apex, Petrous apicitis, Pneumatization of petrous apex

Introduction

The petrous apex is the most medial portion of the temporal bone. Its deep location precludes direct clinical examination and safe percutaneous biopsy. In addition, many of the petrous apex lesions are asymptomatic or present with nonspecific symptoms such as headache, making it harder to justify an invasive procedure for diagnostic purposes. Therefore, the referring physician primarily relies upon imaging for the evaluation of petrous apex abnormalities. Fortunately, many of the petrous apex lesions have characteristic imaging features that allow for correct diagnosis. However, anatomic variations of the petrous apex may mimic an underlying pathology. Hence, the radiologist is required to be familiar with the petrous apex anatomy, normal anatomic variations, and imaging features of the different disease processes to facilitate accurate image interpretation with high degree of confidence.

Anatomy

The petrous apex forms the medial temporal bone and resembles a pyramid, with its tip pointing anteromedially and its base posterolaterally. Its roof forms the floor of the middle cranial fossa and its posterior border constitutes the anterior wall of the posterior cranial fossa. It is separated by the petrosphenoidal fissure from the greater sphenoid wing, the petrooccipital synchondrosis from the occipital bone, and by the petroclival suture from the clivus.

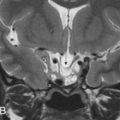

The petrous apex is subdivided into a larger anterior and a smaller posterior portion by the internal auditory canal ( Fig. 11.1 ). The anterior portion usually contains bone marrow, whereas the posterior portion is very dense in appearance, as it derives from the otic capsule ( Fig. 11.1 ). In 30% of patients, the petrous apex is pneumatized via tracts that directly communicate with the middle ear cavity or mastoid air cells. These tracts provide direct “pathways” for spread of diseases from the otomastoid region to the petrous apex and vice versa.

The petrous apex contains a few important neurovascular structures:

- •

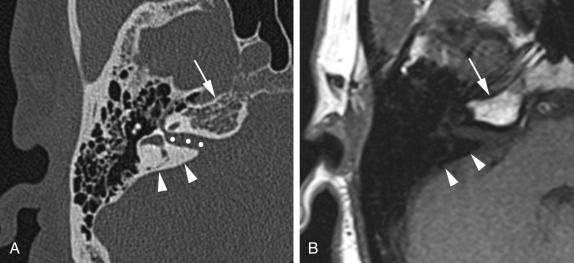

The horizontal carotid canal runs within the anterior petrous bone ( Fig. 11.2 ). It houses the petrous internal carotid artery (ICA) (C2 segment) and the sympathetic plexus. It is separated from the middle ear cavity by a thin, bony lamella that is often demineralized and dehiscent in older patients ( Fig. 11.2 ).

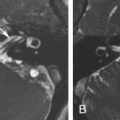

Fig. 11.2

Location of Neurovascular Channels Within the Petrous Apex.

The axial CT image displayed in bone window shows the horizontal carotid canal ( asterisk s) that is located in the anterior petrous apex. It is separated from the middle ear cavity (M) by a thin bony lamella ( arrowhead ) that can get demineralized and partially dehiscent with aging. Notice also the bony notch ( arrow ) along the posterior petrous apex leading to the Dorello canal.

- •

The internal auditory canal (IAC) extends in coronal plane in relationship to the skull. It houses the facial nerve (cranial nerve [CN] VII) in the anterosuperior quadrant, the cochlear nerve in the anteroinferior quadrant, and the superior and inferior divisions of the vestibular nerve in the posterior quadrants. All four nerves are present only within the lateral IAC, as the different branches of the vestibulocochlear nerve (CN VIII) separate in the mid portion of the IAC. Therefore, only two nerves are typically identified in the medial IAC and in the cerebellopontine (CP) cistern. In addition, the inferior vestibular nerve subdivides into the saccular and singular nerves. The singular nerve extends posterolaterally to the vestibule within the singular canal, which is consistently visible on temporal bone CT studies and should not be mistaken for a fracture.

- •

The Dorello canal courses through the petrous apex tip along the petroclival suture. It is bounded by the petrosphenoidal ligament (aka Gruber ligament) superiorly and a small bony notch inferiorly. It houses the abducens nerve (CN VI), which is surrounded by a small venous plexus and a dural sleeve in the posterior canal. Only the bony notch is usually seen on high-resolution CT studies ( Fig. 11.2 ). On MRI, the cerebrospinal fluid-filled dural sleeve may be identified on high-resolution T2 sequences. Occasionally, faint enhancement of the venous plexus is noted, which should not be mistaken for pathology in an asymptomatic patient.

- •

The arcuate canal (aka petromastoid canal) contains the arcuate vessels and courses between the crura of the superior semicircular canal ( Fig. 11.3 ). Owing to its very small size, it is inconsistently visible on imaging and might be mistaken for a fracture.

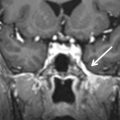

Fig. 11.3

The Arcuate Canal.

Axial CT image displayed in bone window reveals a thin, lucent line ( arrowheads ) between the crura of the superior semicircular canal ( arrows ). This is the characteristic location for the arcuate canal that is inconsistently seen, even on high-resolution CT studies. Therefore, it is sometimes mistaken for a fracture. Petrous apex fractures, however, have a tendency to extend perpendicular to the long axis of the temporal bone and involve the internal auditory canal and/or cochlea (see Fig. 11.8 for comparison).

- •

The Meckel cave, a dural-lined, cerebrospinal fluid-filled pocket within the posterior cavernous sinus, forms a marked depression in the anterosuperior petrous apex. It houses the rootlets of the trigeminal nerve and the trigeminal ganglion (aka Gasserian ganglion) along its inferior boundary.

Clinical Presentations

Patients with petrous apex lesions are typically asymptomatic or present with nonspecific symptoms, e.g., headache or ear pain. As lesions enlarge, they might involve adjacent anatomic structures such as the cavernous sinuses or posterior cranial fossa and present with cranial neuropathies leading to sensorineural hearing loss, vertigo, double vision, facial pain, or facial weakness.

Anatomic Variations and Pathologic Entities of the Petrous Apex

Petrous apex abnormalities can be grouped into five categories based on origin, petrous apex size, and aggressiveness: (1) lesions related to neurovascular channels, (2) intrinsic lesions without petrous apex enlargement, (3) intrinsic lesions with petrous apex enlargement and nonaggressive appearance, (4) intrinsic lesions with aggressive features, and (5) extrinsic petrous apex lesions. Even though some aggressive diseases might manifest without enlargement or destructive features in the early stages of disease, such classification provides a reasonable approach to generate a list of differential diagnostic considerations.

Petrous Apex Lesions Related to Neurovascular Channels

Absence and hypoplasia of the internal carotid artery

Congenital absence or hypoplasia of the ICA is exceedingly rare. Patients are typically asymptomatic because a well-established collateral flow is present through the circle of Willis and more rarely through persistent fetal or extracranial collaterals ( Fig. 11.4 ). The diagnosis is usually made when the patient undergoes vascular imaging for other reasons and confirmed with CT displaying absent or hypoplastic carotid canal ( Fig. 11.4 ). Occasionally, patients present with transient ischemic attacks or congenital, ipsilateral Horner syndrome. Development of intracranial aneurysms, in particular of the anterior communicating artery, is a frequent complication. In addition, patients with intercavernous collaterals are predisposed to catastrophic complications during transphenoidal hypophyseal surgery. Therefore, it is critical for the radiologist to report absent or hypoplastic petrous carotid canal on imaging performed for operative guidance purposes.

Aberrant internal carotid artery

Aberrant ICA is also a very uncommon congenital anomaly related to in utero involution of the cervical ICA and compensatory enlargement of the inferior tympanic and caroticotympanic arteries that connect to the petrous ICA. On imaging, the petrous carotid canal extends posterolaterally into the middle ear cavity to the cochlear promontory. These features are easily identified on axial images. However, in the coronal plane, the lesion at the cochlear promontory might be mistaken for a glomus tumor, as the connection to the petrous segment of the ICA is more difficult to appreciate. Such misinterpretation may lead to uncontrollable bleeding or brain infarction when removal of the aberrant ICA is attempted. Therefore, the radiologist is required to confirm the appropriate position and intactness of the ICA canal when a middle ear cavity mass is present.

Petrous segment internal carotid artery aneurysm

Petrous segment ICA aneurysms are rare, usually asymptomatic, and, hence, typically incidentally detected on imaging for other indications. Occasionally, they cause pulsatile tinnitus, cranial neuropathies, or Horner syndrome. On CT, petrous segment ICA aneurysms manifest as well-defined lytic lesions with variable expansion of the anterior petrous apex. They are often mistaken for a cholesterol granuloma or petrous apex mucocele on CT, with contrasted CT leading to the correct diagnosis unless the aneurysm is thrombosed. On MRI, the aneurysms demonstrate mixed signal intensity and heterogeneous enhancement related to the turbulent flow or thrombus. Characteristic pulsation artifacts in the phase-encoding direction are seen with nonthrombosed aneurysms. MR angiography typically underestimates the size of the aneurysm because of the turbulent flow or thrombus.

Narrow internal auditory canal syndrome

Narrow IAC syndrome is a rare, unilateral temporal bone abnormality that causes congenital sensorineural hearing loss as a result of aplasia or hypoplasia of CN VIII. It represents a relative contraindication to cochlear implantation. CN VII function is typically preserved. On imaging, a small (<2 mm in vertical diameter) duplicated IAC is seen, with one canal containing CN VII and the second canal being empty or housing the hypoplastic CN VIII.

Schwannoma

In the petrous apex region, schwannomas may arise from CN V through VIII, with the vestibular division of CN VIII being most commonly affected. CN VII and VIII abnormalities are discussed in Chapter 7 , Chapter 6 , respectively.

CN V schwannomas are rare and frequently originate from the main trunk or within Meckel cave causing indentation along the superomedial petrous apex. They grow along the nerve and its branches to involve the infratemporal and pterygopalatine fossae and expand the according neural foramina. CN V schwannomas are usually more heterogeneous on imaging than other cranial nerve schwannomas because of their propensity for cystic degeneration.

CN VI schwannomas usually affect the cisternal segment and are exceptionally rare. Preoperatively, they are often misdiagnosed as CN V schwannomas because of their rarity, similar course as CN V schwannomas in the prepontine cistern, and similar imaging features.

Intrinsic Petrous Apex Lesions Without Petrous Apex Enlargement

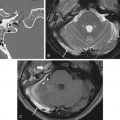

Asymmetric pneumatization

The petrous apex is typically nonaerated, with physiologic pneumatization occurring in about 30% of individuals. In less than 10% of patients, such pneumatization is asymmetric, which is easily recognized with CT. On MRI, however, the nonpneumatized petrous apex is often misinterpreted as cholesterol granuloma in older adults because of the inherent T1 hyperintensity of the fatty bone marrow ( Fig. 11.5 ). Lack of mass effect, striation of the high T1 signal related to preserved bony trabeculae, lower-than-fluid T2 signal intensity on the fast spin echo T2 sequences, and suppression of signal on fat-suppressed T1 weighted images ( Fig. 11.5 ) usually lead to the correct diagnosis. In younger patients, the intermediate T1 and T2 signal intensity of red bone marrow is less likely to be mistaken for a petrous apex lesion.

Petrous apex effusion

Petrous apex effusion (aka trapped fluid) represents fluid accumulation within a pneumatized petrous apex. Often these are asymptomatic and do not require treatment. However, in some patients, this is a manifestation of an indolent infection causing hearing loss, facial spasm, or positional vertigo. Imaging usually reveals fluid attenuation with preservation of the air cell trabeculations ( Fig. 11.6 ). Confusion with a cholesterol granuloma occurs when the trapped fluid is proteinaceous and exhibits T1 hyperintensity. In those instances, the intact air cell septations indicate petrous apex effusion, whereas their absence is more consistent with cholesterol granuloma.

Giant air cell

A petrous apex air cell larger than 1.5 cm represents a giant air cell. When it is filled with fluid, it might be mistaken for a petrous apex mucocele or meningocele. However, the lack of petrous apex expansion and connection to intracranial structures, respectively, usually lead to the correct diagnosis of opacified giant air cell.

Petrous apex cephaloceles

Petrous apex cephaloceles are posterolateral outpouchings of the Meckel cave into the petrous apex. They follow fluid attenuation with possible mild rim enhancement. They are rare and usually asymptomatic, with bilateral involvement in 30% of patients. Surgical intervention is reserved for symptomatic patients who may present with CN III, V, or VI palsy, cerebrospinal fluid leak, or meningitis.

Arachnoid granulations

Arachnoid granulations are small outpouchings of the pia-arachnoid that typically protrude into the venous sinuses or inner table of the skull along the high convexities. They can, however, affect any part of the skull or skull base and mimic an epidermoid cyst or metastasis. On imaging, they are multilobulated, exhibit fluid attenuation, and lack complete disruption of the cortex ( Fig. 11.7 ). They show no or minimal capsule-like enhancement, in contrast to metastasis, and lack restricted diffusion as seen with epidermoid cysts. Occasionally, they protrude into a pneumatized petrous apex and cause a cerebrospinal fluid leak or meningitis.