Although nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is the most common primary malignancy of the nasopharynx, it is an uncommon malignancy in much of the Western world. Over the last several years, there have been important changes in the terminology used for histologic classification of NPC and important changes to the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM staging of NPC. Accurate imaging assessment is critical for diagnose, to stage and plan radiation treatment, and for ongoing follow-up and surveillance. This article emphasizes important nasopharyngeal anatomy landmarks and the imaging appearances and pitfalls of NPC, its patterns of spread, and posttreatment appearances.

Key points

- •

Although nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is the most common primary malignancy of the nasopharynx, it is an uncommon malignancy in much of the Western world.

- •

Over the last several years, there have been important changes in the terminology used for the histologic classification of NPC and important changes to the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM staging of NPC.

- •

Accurate imaging assessment is critical for diagnose, to stage and plan the radiation treatment, and for ongoing follow-up and surveillance.

- •

This article emphasizes important nasopharyngeal anatomy landmarks and the imaging appearances and pitfalls of nasopharyngeal carcinoma, its patterns of spread, and posttreatment appearances.

Introduction

Although nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is the most common primary malignancy of the nasopharynx, it is an uncommon malignancy in much of the Western world where it has an incidence of less than 10 per 1 000 000. Over the last several years, there have been important changes in the terminology used for the histologic classification of NPC and important changes to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging of NPC. Imaging already plays a central role in the evaluation of nasopharyngeal disease because this region may be difficult to examine clinically. With NPC, our clinical colleagues depend on accurate radiologic assessment to diagnose, stage, and plan the radiation treatment and for ongoing follow-up and surveillance. This article emphasizes important nasopharyngeal anatomy landmarks and the imaging appearances and pitfalls of NPC and its patterns of spread and posttreatment appearances. The updated histology and new AJCC TNM staging are presented, emphasizing key changes that are of relevance to the radiologist.

Introduction

Although nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is the most common primary malignancy of the nasopharynx, it is an uncommon malignancy in much of the Western world where it has an incidence of less than 10 per 1 000 000. Over the last several years, there have been important changes in the terminology used for the histologic classification of NPC and important changes to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging of NPC. Imaging already plays a central role in the evaluation of nasopharyngeal disease because this region may be difficult to examine clinically. With NPC, our clinical colleagues depend on accurate radiologic assessment to diagnose, stage, and plan the radiation treatment and for ongoing follow-up and surveillance. This article emphasizes important nasopharyngeal anatomy landmarks and the imaging appearances and pitfalls of NPC and its patterns of spread and posttreatment appearances. The updated histology and new AJCC TNM staging are presented, emphasizing key changes that are of relevance to the radiologist.

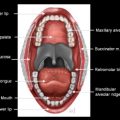

Nasopharyngeal anatomy

The nasopharynx is the most superior portion of the tubular pharynx, located immediately caudal to the central skull base. The inferior limit of the nasopharynx is the soft palate, and it is at this level that the pharynx is deemed oropharynx. The posterior and lateral walls of the nasopharynx are in continuity with the posterior and lateral oropharyngeal walls, respectively. On axial imaging, the nasopharynx is located posterior to the nasal cavity, with which it communicates through the choanae ( Figs. 1 and 2 ). The pharyngobasilar fascia of the superior constrictor muscle, which forms the wall of the nasopharynx, attaches the pharynx to the undersurface of the clivus. There is a small lateral hiatus or opening in this skull base attachment, known as the foramen of Morgagni, through which the eustachian (pharyngotympanic) tube and levator veli palatini muscle pass. The levator veli palatini and the tensor veli palatini muscles are identifiable on magnetic resonance (MR) scans in the lateral wall of the nasopharynx and are responsible for opening the eustachian tube and for tensing and elevating the palate to prevent oronasal reflux (see Fig. 2 ). The eustachian tube communicates with the middle ear, allowing both middle ear aeration and drainage; its opening in the superolateral aspect of the nasopharyngeal wall is marked by the torus tubarius, an elevation of the wall of the nasopharynx formed by the eustachian tube cartilage. The foramen of Morgagni is an essential anatomic structure but is also a potential weak spot in the head and neck through which nasopharyngeal neoplasms or infections may spread directly to the skull base or laterally to the parapharyngeal fat.

The lateral pharyngeal recess (often known by its eponym, the fossa of Rosenmüller) is superolateral to the torus tubarius and the opening of the eustachian tube. On axial images, the lateral pharyngeal recess is located posterior to the torus tubarius and it is superior to the torus tubarius on coronal images (see Fig. 1 ). It is within the lateral recess (fossa of Rosenmüller) that most nasopharyngeal carcinomas arise.

The midline posterior nasopharyngeal wall connecting the two lateral recesses is superficial to the prevertebral longus capitis and longus colli muscles that attach to the basiocciput and upper cervical vertebrae. The posterior nasopharyngeal wall, as well as the roof or vault in younger patients, is the location of the nasopharyngeal tonsillar tissue or adenoids. Adenoidal hypertrophy in response to infection may mimic neoplastic enlargement or a nasopharyngeal mass. However, reactive hypertrophy is never associated with invasion of the prevertebral muscles, and these structures are clearly delineated on MR imaging.

The overall shape of the nasopharyngeal cavity varies depending on the bulk of the prevertebral muscles and the adenoids. In older patients, the nasopharynx may appear enlarged but shallow with loss of muscle bulk and atrophy of the adenoids, whereas the nasopharyngeal cavity may be entirely obliterated in children by large adenoids.

Epidemiology of NPC

There have been many changes to the terminology used for the classification of NPC. Currently, the World Health Organization (WHO) divides NPC into a histologic classification of 4 types, with epidemiology reflecting the different pathologic types ( Table 1 ). Broadly defined, NPC is defined as keratinizing (previously termed type I or squamous cell carcinoma), nonkeratinizing (NK), and basaloid squamous cell carcinoma (BSCC). NK NPC is further subdivided into differentiated (previously termed type II or transitional carcinoma) and undifferentiated (previously termed type III or lymphoepithelioma).

| WHO Classification | Previous Terminologies | Epidemiology | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Keratinizing | Type I, squamous cell carcinoma | ∼25% NPC cases Rare <40 y of age Men greater than women Weak EBV association Environmental risk factors | 20%–40% 5-y survival |

| Nonkeratinizing | Overall ∼75% NPC cases Most common fifth to seventh decades 70% men, 30% women Strong EBV association Genetic & environmental risk factors | ||

| Differentiated | Type II, transitional carcinoma | ∼15% NPC cases | ∼75% 5-y survival |

| Undifferentiated | Type III, lymphoepithelial carcinoma | ∼60% NPC cases May occur in children | ∼75% 5-y survival |

| BSCC | Rare Sixth to seventh decades, mean age = 55 y Men greater than women Associated with excessive alcohol and tobacco use | Seems to be less aggressive than BSCC in other sites but overall poor prognosis |

NK NPC is the most common form, with undifferentiated NK being approximately 4 times as common as the differentiated form. The subtypes of NK NPC share the same proposed epidemiologic and etiologic factors. Both are strongly associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection, are most commonly found in Asian (particularly Chinese) men, and are most often found in patients from 40 to 80 years of age. Although pediatric NPC is relatively rare, undifferentiated NK NPC is the most common form. The incidence rate of NPC at less than 20 years of age is higher for African Americans than for American Asians. NK NPC is highly radiosensitive, which results in reasonably good 5-year survival statistics of approximately 75%.

Keratinizing NPC was previously termed NPC type I and is the histologic type found in approximately a quarter of NPC cases. It is graded as poorly, moderately, or well differentiated, with well differentiated being the least commonly occurring. Keratinizing NPC is not typically associated with EBV but is associated with cigarette smoking; prior radiation; and occupational exposures, such as to chemical fumes, smoke, and formaldehyde. Five-year survival is significantly lower for keratinizing NPC (20%–40%) and this is largely because of poor local control. The US statistics for relative survival at 5 years from diagnosis overall for all nasopharyngeal carcinomas varies from 47% to 78% depending on the tumor stage at presentation of stage IV to stage I, respectively.

Another common malignancy to involve the nasopharynx is lymphoma arising in or secondarily affecting the adenoid tissue. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is the most common type to affect the Waldeyer ring and is weakly associated with EBV infection. Lymphoma mimics NPC on imaging and can be a diagnostic dilemma for the radiologist. However, lymphoma is more commonly midline in origin; when invading the skull base, it tends to expand the clivus rather than just infiltrate the marrow.

Other uncommon malignancies that involve the nasopharyngeal mucosa include adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC) and small cell undifferentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma (SCNEC). There is a rare nasopharyngeal papillary adenocarcinoma (NPPA) that most often presents as an exophytic obstructing nasopharyngeal mass. This slow-growing low-grade neoplasm does not typically metastasize and is cured by complete excision. There are no known viral or environmental etiologic factors for ACC, SCNEC, or NPPA.

AJCC seventh edition staging

The seventh edition of the AJCC, published in January 2010, brought important changes to the way in which NPC is staged and these were largely simplifications of the prior system. With regard to staging the primary tumor site (T stage), it has been determined that tumors extending to the oropharynx or nasal cavity (previously staged as T2a) did not have a worse prognosis than tumors confined to the nasopharynx (T1) and so are now staged as T1 ( Box 1 , Fig. 3 ). Parapharyngeal space extension, which is posterolaterally spread through the pharyngobasilar fascia to the parapharyngeal fat, denotes T2 stage ( Fig. 4 ). T3 and T4 designations remain unchanged from the prior AJCC staging system ( Figs. 5 and 6 ).

Primary tumor (T)

TX: Primary tumor cannot be assessed

T0: No evidence of primary tumor

Tis: Carcinoma in situ

T1: Tumor confined to the nasopharynx or extends to oropharynx and/or nasal cavity without parapharyngeal extension

T2: Tumor extends to parapharyngeal fat

T3: Tumor involves bone of skull base and/or paranasal sinuses

T4: Intracranial extension and/or involvement of cranial nerves, orbit, hypopharynx, and/or extension to the infratemporal fossa or masticator space

Regional lymph nodes (N)

NX: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed

N0: No regional lymph node metastasis

N1: Unilateral nodes 6 cm or less in greatest dimension and/or unilateral or bilateral retropharyngeal nodes 6 cm or less in greatest dimension

N2: Bilateral nodes 6 cm or less in greatest dimension

N3: Metastasis in a lymph node more than 6 cm in greatest dimension or extension to supraclavicular fossa

N3a: Nodes 6 cm or more in dimension

N3b: Nodal metastasis in supraclavicular fossa

Distant Metastasis (M)

M0: No distant metastasis

M1: Distant metastasis